Interim Assessment of Progress June 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tel-Aviv Metro M1 North Assessment of NTA Planning

Tel-Aviv metro M1 North Assessment of NTA planning for The region of Drom Hasharon and the municipalities of Herzliya – Kfar Saba – Raanana – Ramat Hasheron doc.ref.: M1-North-Planning-NTA-Assessment-v06.docx version: 0.6 date: 18-01-2021 author: Dick van Bekkum Copyright © 2020/2021 MICROSIM Maisland 25 3833 CR Leusden The Netherlands Assessment of NTA plans M1 North Contents 0. Assessment Statement ............................................................................................................. 3 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Planning of M1 .................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Assessment of plans ........................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Technical assumptions ........................................................................................................ 4 1.4 Structure of this document ................................................................................................... 6 2. Construction technology and logistics ....................................................................................... 6 3. Noise and vibration................................................................................................................... 6 4. Electro Magnetic Compatibility ................................................................................................. -

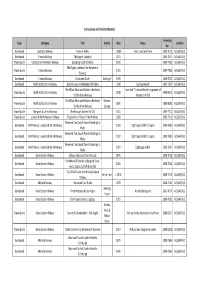

Publicity Material List

Early Guides and Publicity Material Inventory Type Company Title Author Date Notes Location No. Guidebook Cambrian Railway Tours in Wales c 1900 Front cover not there 2000-7019 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook Furness Railway The English Lakeland 1911 2000-7027 ALS5/49/A/1 Travel Guide Cambrian & Mid-Wales Railway Gossiping Guide to Wales 1870 1999-7701 ALS5/49/A/1 The English Lakeland: the Paradise of Travel Guide Furness Railway 1916 1999-7700 ALS5/49/A/1 Tourists Guidebook Furness Railway Illustrated Guide Golding, F 1905 2000-7032 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook North Staffordshire Railway Waterhouses and the Manifold Valley 1906 Card bookmark 2001-7197 ALS5/49/A/1 The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Inscribed "To Aman Mosley"; signature of Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1908 1999-8072 ALS5/29/A/1 Staffordshire Railway chairman of NSR The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Moores, Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1891 1999-8083 ALS5/49/A/1 Staffordshire Railway George Travel Guide Maryport & Carlisle Railway The Borough Guides: No 522 1911 1999-7712 ALS5/29/A/1 Travel Guide London & North Western Railway Programme of Tours in North Wales 1883 1999-7711 ALS5/29/A/1 Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7680 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7681 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, -

Issue #30, March 2021

High-Speed Intercity Passenger SPEEDLINESMarch 2021 ISSUE #30 Moynihan is a spectacular APTA’S CONFERENCE SCHEDULE » p. 8 train hall for Amtrak, providing additional access to Long Island Railroad platforms. Occupying the GLOBAL RAIL PROJECTS » p. 12 entirety of the superblock between Eighth and Ninth Avenues and 31st » p. 26 and 33rd Streets. FRICTIONLESS, HIGH-SPEED TRANSPORTATION » p. 5 APTA’S PHASE 2 ROI STUDY » p. 39 CONTENTS 2 SPEEDLINES MAGAZINE 3 CHAIRMAN’S LETTER On the front cover: Greetings from our Chair, Joe Giulietti INVESTING IN ENVIRONMENTALLY FRIENDLY AND ENERGY-EFFICIENT HIGH-SPEED RAIL PROJECTS WILL CREATE HIGHLY SKILLED JOBS IN THE TRANS- PORTATION INDUSTRY, REVITALIZE DOMESTIC 4 APTA’S CONFERENCE INDUSTRIES SUPPLYING TRANSPORTATION PROD- UCTS AND SERVICES, REDUCE THE NATION’S DEPEN- DENCY ON FOREIGN OIL, MITIGATE CONGESTION, FEATURE ARTICLE: AND PROVIDE TRAVEL CHOICES. 5 MOYNIHAN TRAIN HALL 8 2021 CONFERENCE SCHEDULE 9 SHARED USE - IS IT THE ANSWER? 12 GLOBAL RAIL PROJECTS 24 SNIPPETS - IN THE NEWS... ABOVE: For decades, Penn Station has been the visible symbol of official disdain for public transit and 26 FRICTIONLESS HIGH-SPEED TRANS intercity rail travel, and the people who depend on them. The blight that is Penn Station, the new Moynihan Train Hall helps knit together Midtown South with the 31 THAILAND’S FIRST PHASE OF HSR business district expanding out from Hudson Yards. 32 AMTRAK’S BIKE PROGRAM CHAIR: JOE GIULIETTI VICE CHAIR: CHRIS BRADY SECRETARY: MELANIE K. JOHNSON OFFICER AT LARGE: MICHAEL MCLAUGHLIN 33 -

Police Resource Management: Patrol, Investigation, Scheduling

Law Enforcement Executive FORUM Police Resource Management: Patrol, Investigation, Scheduling September 2006 Law Enforcement Executive Forum Illinois Law Enforcement Training and Standards Board Executive Institute Western Illinois University 1 University Circle Macomb, IL 61455 Senior Editor Thomas J. Jurkanin, PhD Editor Vladimir A. Sergevnin, PhD Associate Editors Jennifer Allen, PhD Department of Law Enforcement and Justice Administration Western Illinois University Barry Anderson, JD Department of Law Enforcement and Justice Administration Western Illinois University Tony Barringer, EdD Division of Justice Studies Florida Gulf Coast University Lewis Bender, PhD Department of Public Administration and Policy Analysis Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville Michael Bolton, PhD Chair, Department of Criminal Justice and Sociology Marymount University Dennis Bowman, PhD Department of Law Enforcement and Justice Administration Western Illinois University Weysan Dun Special Agent-in-Charge, FBI, Springfield Division Kenneth Durkin, MD Department of Law Enforcement and Justice Administration Western Illinois University Thomas Ellsworth, PhD Chair, Department of Criminal Justice Sciences Illinois State University Larry Hoover, PhD Director, Police Research Center Sam Houston State University William McCamey, PhD Department of Law Enforcement and Justice Administration Western Illinois University John Millner State Senator of 28th District, Illinois General Assembly Michael J. Palmiotto Wichita State University Frank Morn Department of -

Harakevet133.Pdf

Series 35#2 Issue 133 June 2021 ����� ISSN - 0964-8763 133:02 133:04. (i). ELECTRIFICATION WORKS CONTINUE. Without wishing to get too morbid, the last issue was put together just as the Editor had lost his mother at the age of 96 and as Steve, who does so Israel Railways Ltd. announced on their website that due to track upgrading much for the layout, printing and despatch had lost his brother aged 88. While works the line between Beer-Sheva and Dimona would be closed for passenger we both struggled with other emotions we were exchanging e-mails, hunting traffic from Sunday 07.03.2021 at 05:00 until Sunday 14.03.2021 at 05:00. maps that got 'lost' in the system, correcting typos and so forth. And this is Due to electrification works, there are some changes to timetables of trains meant to be a 'hobby'! on the Ashkelon – Ashdod – Tel-Aviv – Herzliya line, at the stations of Rehovot Work on this issue went ahead rather placidly with much help from several and Rishon-LeZion HaRishonim and with some direct trains between Tel-Aviv people in several countries who sent information, but then in mid-May all hell and Haifa from 03.03.2021 between 05:00 and 06:00 and between 19:00 broke out once again with rocket attacks from Gaza into Central Israel, and and 20:00, so it will hardly disrupt passenger services. disturbances on top of this, affecting Tel Aviv, Lod, Modiin, Beersheba and more. At the time of writing the scene remains very confused, all we can say is that despite the mayhem and bloodshed there is as yet no information on (ii). -

Israel National Report

Israel National Report Eighteenth Session of the Commission on Sustainable Development April 2010 ISRAEL NATIONAL REPORT TO CSD – 18 THEME-SPECIFIC ISSUES CHEMICALS Introduction The chemical industry plays an important part in Israel's economic development, comprising some 20% of GDP by industry and a growing share of the country's exports (from 11.1% in 2000 to 22.1% in 2008). Safe use and regulation of chemicals is an essential component of Israel's environmental policy. The main frameworks for chemical management in Israel are the Licensing of Businesses Law, 1968 and the Hazardous Substances Law, 1993. Enforcement includes supervision on the sales and acquisition of chemicals and supervision on the import of chemicals (by Israeli Customs). Moreover, in recent years, an Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control (IPPC) approach was introduced into the major industrial hotspots: Ramat Hovav in the south, Ashdod on the southern Mediterranean coast and Haifa Bay in the north of the country. Assessment of Chemical Risks Mechanisms for systematic evaluation, classification, and labeling of chemicals, including initiatives towards a harmonized system of classification and labeling of chemicals At present, the existing frameworks for industrial chemical management in Israel regulate the user of chemicals by means of stringent measures for "cradle to grave" supervision of the production, import, storage, storage, processes, wastes and transport of chemicals. A tender for comparative analysis of different chemical management systems, including REACH in Europe and TSCA in the USA, was published in 2010, to be followed by selection of the preferred mechanism for chemical management in 2011. It is anticipated that a new administrative unit for chemical assessment and registration will be set up in 2012 and that implementation will commence in 2013. -

International Airport in France

GLOBAL TOURISM GEOGRAPHY UNIT - V Contents • Transport in Europe & Trans-Siberian • Transport in Far East • Transport in Middle East • Transport in Australia 5.1. Transport in Europe & Trans-Siberian The main international trains operating in Europe are: • Enterprise (Republic of Ireland & Northern Ireland (UK)) • Eurostar (United Kingdom, France, Belgium, Netherlands) • EuroCity/EuroNight (conventional trains operated by nearly all Western and Central European operators, with the notable exception of the UK and Ireland) • Intercity Direct (Netherlands, Belgium) • InterCityExpress (Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, France, Denmark, Switzerland, Austria) • TGV (France, Belgium, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, Germany, Luxembourg) • Thalys (France, Germany, Belgium, Netherlands) Contd.. • Railjet (Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Hungary, Czechia, Italy, Slovakia) • Elipsos (France, Spain) • Trenhotel (France, Spain, Portugal) • Oresundtrain (Denmark, Sweden) • SJ 2000 (Sweden, Norway, Denmark) • NSB (Sweden, Norway) • Allegro (Finland, Russia) • Belgrade-Bar Railway (Serbia, Montenegro) These are the biggest European airlines for 2020 by passengers flown during 2019 • Ryanair, 152 million. • Lufthansa Group, 145 million. • IAG (British Airways, Iberia, Vueling, Aer Lingus), 118 million. • easyJet, 96.1 million. • Air France-KLM, 87.6 million. • Turkish Airlines, 74.2 million. • Aeroflot, 60.7 million. Top 5 Airports in Europe • 1 – Heathrow Airport. • 2 – Charles de Gaulle Airport. Charles de Gaulle Airport is the largest international airport in France. ... • 3 – Amsterdam Airport. ... • 4 – Frankfort Airport. ... • 5 – Madrid-Barajas Adolfo Suarez Airport. Trans-Siberian Network Trans-Siberian Railway Facts • Longest continuous railway on Earth: 5,772 miles • Proposed in 1850s by Perry McDonough Collins, American traveler who took seven months to travel overland from Moscow to Pacific. • Before railway, fastest route from Moscow to Vladivostok was 40 days by sea. -

Supplement J¡5O. 2 To

Supplement j¡5o. 2 to %pt paimint C&mtttt Bo 1073 of 16ty %mum, 1941. : DEFENCE (MILITARY COMMANDERS) REGULATIONS, 1938. NOTICE. IN VIRTUE of the powers vested in me by the Defence "(Military Commanders) Re• gulations, 1938, I, PHILIP NEAME, on whom His Majesty has conferred the Victoria Cross, Companion of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath, Companion of the Distinguished Service Order, Lieutenant-General Commanding the Forces in Pal• estine and Trans-Jordan, with the consent of the High Commissioner, do hereby ap• point COLONEL DENNISON ALFRED WILKINS, Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, to be Military Commander of the Area of Place known as the Haifa District from the third day of January, 1941, and until further notice, vice BRIGADIER ALAN MACDOUGAL RITCHIE, Companion of the Distinguished Service Order. P. NEAME .;• Lieutenani-General, General Officer Commanding, British Forces in Palestine and Trans-Jordan. (SF/917/38) ; WORKMEN'S COMPENSATION ORDINANCE. NOTICE. •:•.•:!.. I have been empowered by the Chief Secretary to the Govern• ment, of Palestine to collect the annual returns of injuries and compensation required from employers of labour in employments to which the Workmen's Compensation Ordinance is applicable. CAP• 15*•' —.79 — — 80 — These returns are required in respect of calendar years and have to be furnished to the Office of Statistics, P.O.B. 498, Jerusalem, not later than the 1st December in each year in respect of the pre-• vious calendar year. The returns for the calendar year 1940 should be sent to me not later than the 1st December, 1941. -

TÜRK DÜNYASI Dil Ve Edebiyat Dergisi

Türk Dil Kurumu Yayınları TÜRK DÜNYASI Dil ve Edebiyat Dergisi Sayı: 50 / Güz 2020 Ankara, 2020 Türk Dünyası Dil ve Edebiyat Dergisi Doksanlı yıllarda Türk dünyasıyla ilişkilerin artmasıyla birlikte, Türkiye ile Türk Cumhuriyetleri arasında Türk dünyasının dili, sanatı ve tarihine yönelik ortak çalışmalar da artmıştır. Bu dönemde Türk Dil Kurumu da Türk dünyasına yönelik çalışmalarını sözlük, gramer ve metin yayınları üzerinde yoğunlaştırmış, konuyla ilgili çok sayıda eser yayımlamıştır. Türk dünyasıyla ilgili benzer çalışmaların süreli bir yayın kapsamında değerlendirilmesi amacıyla 1996 yılının Nisan ayında Türk Dünyası Dil ve Edebiyat Dergisi yayın hayatına girmiştir. Türk Dünyası Dil ve Edebiyat Dergisi çok geniş bir coğrafyaya yayılan Türklerin dil, tarih ve kültürel iş birliğine yönelik edebî ve ilmî bütün çalışmaları okuyucusuna duyurmayı ilke edinmiştir. Buna bağlı olarak dergide Türk yazı dilleri, lehçeleri ve edebiyatlarının tarihî ve günümüzdeki özelliklerini, eserlerini, yazarlarını, sorunlarını ele alan ilmî yazılarla dil ve edebiyat araştırmalarına yer verilmektedir. Milletlerarası hakemli bir dergi olan Türk Dünyası Dil ve Edebiyat Dergisi Bahar (Mart) ve Güz (Ekim) sayıları olmak üzere yılda iki sayı yayımlanmaktadır. Genel ağ (internet) üzerinden bütün Türk dünyasından kolayca erişilebilir hâle getirilen dergiye özellikle son dönemlerde bu alandan önemli katkılar sağlanmaktadır. Dergideki yazılara Türk Dil Kurumu genel ağ sayfasından ve TÜBİTAK/ Dergipark üzerinden erişilebilmektedir. Dergide yayımlanan yazılar için yazarlarına -

Minnesota Statewide Historic Railroads Study Final MPDF

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB No. 1024-0018 (8-86) Expires 12-31-2005 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section: E Page 5 Railroads in Minnesota, 1862-1956 Name of Property Minnesota, Statewide County and State Section E. Statement of Historic Contexts I. Railroad Development in Minnesota, 1862-1956 Setting the Stage: Early Railroads Due to the country’s vast geographic expanse, transportation has always been a significant issue in America, influencing production, trade, travel, and communication in ways unknown to more compact European nations. In particular, as Euro-American settlers streamed into the trans-Appalachian west during the early nineteenth century, the United States needed an overland transportation system to link different regions of the country. From early roads to canals and finally to railroads, Americans built a transportation system by the turn of the twentieth century that was larger and more complex than any other in the world. The transformation of transportation in America began with the era of canal building. Although a system of roads extending westward from the major seaports had been established by 1820, water-borne transportation was more efficient for shipping heavy freight and generally faster than overland transport. Completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 demonstrated that canals could be built over long distances to connect major waterways and could be operated profitably. The immediate success of the Erie Canal led to a canal building boom that lasted through the 1830s. The network of canals and natural waterways provided antebellum America with important interregional links to exchange raw materials and manufactured goods, to transport passengers, and to deliver mail. -

Issue 10 Is Overflowing, and I Have Lots More Material to Publish in Future Issues

1. I. Binyamina Station on 24/1/90, shortly after the platform canopy had been erected and other improvements carried out. 107 is running through with train 26 (the 10.30 non-stop express from Tel Aviv to Haifa). Standing alongside is 124 on station pilot duties. Plans call for a second platform to be built at Binyamina, which would mean the destruction of the freight shed at the right of this picture. (Photo: Paul Cotterel I ). 10.2. ED I TOR I Al_. Issue 10 is overflowing, and I have lots more material to publish in future issues. Articles are still welcome, though! I have had many favourable comments on the switch to A5 format - thanks. There are a few corrections to No. 9 necessary: The cover photo is at Jerusalem, not Lydda; photos of "Terezina" on page 10 were omitted in error by the printer, but are reproduced in this issue instead; and the article by Paul CotterelI on p. 27 should have a title, "The Good Old Days", which got knocked off when trying to reduce the A4 sheet down to A5; that article should also have been numbered 9:22. In 9:9, the Negev Phosphates bo-bo was overhauled at the Haifa diesel maintenance depot, only the bogies being sent to Qishon Works for attention. The loco’s livery is yellow with a maroon lightning flash. In 8: 13, the introduction referred to the G26CW and G26CW-2 Co-Cos, nos. 601 - 615. but the actual drawing was of GT26CW-2 No. 701. (Is this the Gran Turismo version ?) Alas. -

UNDER the SHADOW of the RISING SUN JAPAN and the JEWS DURING the HOLOCAUST ERA Series Editor: Roberta Rosenberg Farber (Yeshiva University)

UNDER THE SHADOW OF THE RISING SUN JAPAN AND THE JEWS DURING THE HOLOCAUST ERA Series Editor: Roberta Rosenberg Farber (Yeshiva University) Editorial Board Sara Abosch (University of Memphis) Geoffrey Alderman (University of Buckingham) Yoram Bilu (Hebrew University) Steven M. Cohen (Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion) Bryan Daves (Yeshiva University) Sergio Della Pergola (Hebrew University) Simcha Fishbane (Touro College) Deborah Dash Moore (University of Michigan) Uzi Rebhun (Hebrew University) Reeva Simon (Yeshiva University) Chaim I. Waxman (Rutgers University) UNDER THE SHADOW OF THE RISING SUN JAPAN AND THE JEWS DURING THE HOLOCAUST ERA Meron Medzini BOSTON 2016 Effective January 8th, 2018, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Medzini, Meron, author. Title: Under the shadow of the rising sun : Japan and the Jews during the Holocaust era / Meron Medzini. Other titles: Be-tsel ha-shemesh ha-°olah. English Description: Boston : Academic Studies Press, 2016. Series: Jewish identities in post-modern society Identifiers: LCCN 2016037874 (print) | LCCN 2016038066 (ebook) | ISBN 9781618115225 (hardback) | ISBN 9781618115232 (e-book) Subjects: LCSH: Jews—Japan—History—20th century.