94066 the X Factor Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remee-December-2017.Pdf

Interview / Remee Blå Bog Remee (Remee Sigvardt Jackman – Sigvardt efter adoptivfamilien, Jackman efter hans biologiske far) er født i 1974. Han fik pladekon- trakt allerede i 1989, men blev for alvor kendt som en del af dance-trioen Sound of Seduction fra 1992. Sideløbende indledte han et samarbejde med Thomas Blachman i dennes fusionsprojekt, der blandede jazz og hiphop. Siden ”Uanset hvad vi måtte ønske, har han især udmærket sig som sangskriver og producer af både så bliver det pik-måleri at danske og udenlandske hits. Remee har udgivet og komponeret mere være X Factor-dommere” end 500 sange, solgt over 30 mil- lioner plader, vundet Ivor Novello Awards, Grammyer, X Factor 4 gange (3 år i træk, som den eneste dommer i verden i alle tre katego- rier), Melodi Grand Prix 2 gange i Danmark og 1 gang i Tyskland. Remee var dommer i første udgave af X Factor og er siden blevet forbundet med det samt med sine natklubber – lige nu ARCH, som er ved at udvide. Ejer også social media selskabet “Social-Works” (influenceragency.com) Privat har Remee netop friet til sin kæreste (og mor til datteren Kenya) Mathilde Gøhler … og hun har sagt ja. Han har desuden datteren Emma fra et tidligere forhold. 42 Liebhaverboligen #202 December 2017 Interview / Ellen Hillingsø DET PERFEKTE ØJEBLIK Det perfekte øjeblik har altid været omdrejningspunktet for Remee. Det gælder når dansegulvet koger på natklubben ARCH, det gælder når han hjælper en talentfuld kunstner i X Factor. Som til januar ruller over skærmen for sidste gang i DR regi. STEEN BLENDSTRUP ALEKSANDAR K EMILIE AAGAARD ANDREASSEN FOR ZENZ ORGANIC ige tilføjelsen ’i DR regi’ er Fremmede, der giver os gåsehud vigtig. -

Babas, Michael Solmirin, Aug. 6, 2008 Michael Solmirin Babas, 47, of Waipahu, an Air Force Retiree, Died in Hawaii Medical Center-West

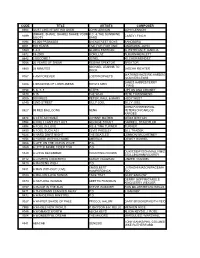

Babas, Michael Solmirin, Aug. 6, 2008 Michael Solmirin Babas, 47, of Waipahu, an Air Force retiree, died in Hawaii Medical Center-West. He was born in Guam. He is survived by wife Dianne; sons Adrian M., Anthony and Allan; daughter Arika; father and mother Jaime and Magdalena; brothers Jaime Jr., Robert, Richard, Rodney and Glenn; sisters Gloria Ann Banas and Beverly Cruz; and three grandchildren. Services: 2 p.m. Monday at Schofield Barracks Main Post Chapel Building 791 on McCornack Road, Wahiawa. Call after 1:30 p.m. Burial: 1 p.m. at Schofield Post Cemetery. Flag indicates service in the U.S. armed forces. [Honolulu Star Bulletin 15 August 2008] BACLAAN, GARY, 54, of 'Ewa Beach, died July 17, 2008. Born in 'Aiea. Survived by father, Gulielmus "Mingky"; stepmother, Lorna; brothers, Manuel, Lawrence and Eugene Lacanaria, Alan, Isaiah and Elijah Baclaan; sisters, Helen Ebia, Rosemarie Zane, Miriam Inay, Gloria Jean Billinger, Ronnie Rhoades and Valerie McCormack; nieces; nephews. Visitation 5:30 p.m. Saturday at Mililani Mortuary Makai Chapel; service 6:30 p.m. Flowers welcome. Casual/aloha attire. [Honolulu Advertiser 23 July 2008] BACLAAN, IGNACIO “NAS,” 82, of „Aiea, died Oct. 13, 2008. Born in „Ewa. Retired Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard Shop No. 56 pipefitter; U.S. Army vertran. Survived by wife, Rosie; sons, Richard, George, Steven, Darrell and Jonah; daughters, Geraldine Fujikawa, Cynthia Baclaan, Gwendolyn Brunosky, Stephanie and Leann; 24 grandchildren; 24 great-grandchildren; brothers, Benny, Lawrence and Alfred; sister, Marie Bacoro. Visitation 9 a.m. Wednesday at Mililani Mortuary Mauka Chapel; eulogy and service 10 a.m.; burial 11 a.m. -

Skatteretlig Kvalifikation Af Musikere Skatteretlig Kvalifikation Af Musikere

Cand.merc.aud. studiet Afleveringsdato: 3. Maj 2010 Institut for regnskab og revision Kandidatafhandling Skatteretlig kvalifikation af musikere og opgørelse af indkomsten skrevet af: Line Dedenroth Strøm Copenhagen Business School – 2010 Vejleder: Ole Aagesen Antal anslag: 181.702 Skatteretlig kvalifikation af musikere – og opgørelse af indkomsten 333.3...mmmmaaaajjjj 2010 Indholdsfortegnelse 1. Executive summer 4 2. Forord 5 3. Indledning 5 4. Problemformulering 6 4.1Overordnet formål 6 4.2 Præcisering af problemformulering 7 4.3 Samfundsøkonomisk formål med afhandlingen 7 4.4 Afgrænsning 8 5. Model- og metodevalg 9 5.1 Afhandlingens struktur 9 5.2. Diskussion af civilrettens styring af skatteretten 10 5.3 Teoretisk metode 12 5.3.1 Retskildernes rangorden 12 6. Grundlæggende principper for indkomstbeskatning i Danmark. 13 6.1 Subjektiv skattepligt 14 6.2 Objektiv skattepligt 15 6.2.1 Periodisering 17 6.2.1.1 Beskatningstidspunktet 17 6.2.1.2 Fradragstidspunktet 17 6.3 Delkonklusion 18 7. Den generelle retstilstand for lønmodtager, selvstændigt erhvervsdrivende, 19 honorarmodtager og hobbyvirksomhed. 1 Skatteretlig kvalifikation af musikere – og opgørelse af indkomsten 333.3...mmmmaaaajjjj 2010 7.1 Indledning 19 7.2 Afgrænsning af lønmodtageren 20 7.3 Afgrænsning af selvstændig erhvervsdrivende 21 7.4 Afgrænsning af honorarmodtagere 23 7.5Afgrænsning af hobbyvirksomhed og anden ikke - erhvervsmæssig virksomhed 24 8. Generelle beskatningsregler for de forskellige indkomsttyper. 26 8.1 Indledning 26 8.2 Fælles regler uanset indkomsttype 26 8.3 Den generelle skatteretlige behandling af lønmodtageren 27 8.4 Den generelle skatteretlige behandling af den selvstændigt erhvervsdrivende 31 8.4.1 Beskatning efter PSL 32 8.4.2 Beskatning efter Virksomhedsordningen 33 8.4.3 Kapitalafkastordningen. -

Inside Official Singles & Albums • Airplay Charts

ChartPack cover_v3_News and Playlists 08/04/13 13:56 Page 35 CHARTPACK Duke Dumont is at No.1 in the Official Singles Chart this week with Need U (100%) feat A*M*E & MNEK - as Justin Timberlake returns to the albums summit INSIDE OFFICIAL SINGLES & ALBUMS • AIRPLAY CHARTS • COMPILATIONS & INDIE CHARTS 52-53 Singles-Albums_v1_News and Playlists 08/04/13 11:33 Page 28 CHARTS UK SINGLES WEEK 14 For all charts and credits queries email [email protected]. Any changes to credits, etc, must be notified to us by Monday morning to ensure correction in that week’s printed issue The Official UK Singles and Albums Charts are produced by the Official Charts Company, based on a sample of more than 4,000 record outlets. They are compiled from actual sales last Sunday to Saturday, THE OFFICIAL UK SINGLES CHART THIS LAST WKS ON ARTIST / TITLE / LABEL CATALOGUE NUMBER (DISTRIBUTOR) THIS LAST WKS ON ARTIST / TITLE / LABEL CATALOGUE NUMBER (DISTRIBUTOR) WK WK CHRT (PRODUCER) PUBLISHER (WRITER) WK WK CHRT (PRODUCER) PUBLISHER (WRITER) 1 DUKE DUMONT FEAT. A*M*E & MNEK Need U (100%) MoS/Blas? Boys Club GBCEN1300001 (ARV) 39 29 8 BAAUER Harlem Shake Mad Decent USZ4V1200043 (C) N (Duke Dumont/Forrest) EMI/Kobalt/San Remo Live/CC (Dyment/Kabba/Emenike) (Baauer) CC (Rodrigues) 2 29 PINK FEAT. NATE RUESS Just Give Me A Reason RCA USRC11200786 (ARV) 40 IMAGINE DRAGONS It’s Time Interscope USUM71200987 (ARV) (Bhasker) Sony ATV/EMI Blackwood/Pink Inside/Way Above (Pink/Bhasker/Ruess) N (tbc) tbc (tbc) 3 48 JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE Mirrors RCA USRC11300059 (ARV) 41 35 27 RIHANNA Diamonds Def Jam USUM71211793 (ARV) 1# (Timbaland/Timberlake/Harmon) Universal/Warner Chappell/Tennman Tune/Z Tunes/J.Harmon/J.Fauntleroy/Almo (Timberlake/Mosley/Harmon/Godbey/Fauntleroy) (B.Blanco/StarGate) EMI/Kobalt/Matza Ball/Where Da Kasz At (Furler/Eriksen/Hermansen/Levine) 4 33 THE SATURDAYS FEAT. -

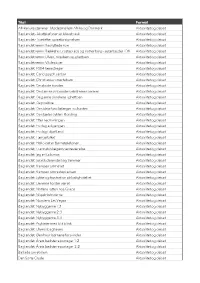

Code Title Artists Composer 8664 (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon John Lennon (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your K.C

CODE TITLE ARTISTS COMPOSER 8664 (JUST LIKE) STARTING OVER JOHN LENNON JOHN LENNON (SHAKE, SHAKE, SHAKE) SHAKE YOUR K.C. & THE SUNSHINE 8699 CASEY / FINCH BOOTY BAND 8094 10,000 PROMISES BACKSTREET BOYS SANDBERG 8001 100 YEARS FIVE FOR FIGHTING ONDRASIK, JOHN 8563 1-2-3 GLORIA ESTEFAN G. ESTEFAN/ E. GARCIA 8572 19-2000 GORILLAZ ALBARN/HEWLETT 8642 2 BECOME 1 JEWEL KILCHER/MENDEZ 9058 20 YEARS OF SNOW REGINA SPEKTOR SPEKTOR MICHAEL LEARNS TO 8865 25 MINUTES JASCHA RICHTER ROCK WATKINS/GAZE/RICHARDSO 8767 4 AM FOREVER LOSTPROPHETS N/OLIVER/LEWIS JAMES HARRIS/TERRY 8208 4 SEASONS OF LONELINESS BOYZ II MEN LEWIS 9154 5, 6, 7, 8 STEPS LIPTON AND CROSBY 9370 5:15 THE WHO PETE TOWNSHEND 9005 500 MILES PETER, PAUL & MARY HEDY WEST 8140 52ND STREET BILLY JOEL BILLY JOEL JOEM FAHRENKROG- 8927 99 RED BALLOONS NENA PETERSON/CARLOS KARGES 8674 A CERTAIN SMILE JOHNNY MATHIS WEBSTER/FAIN 8554 A FIRE I CAN'T PUT OUT GEORGE STRAIT DARRELL STAEDTLER 8594 A FOOL IN LOVE IKE & TINA TURNER TURNER 8455 A FOOL SUCH AS I ELVIS PRESLEY BILL TRADER 9224 A HARD DAY'S NIGHT THE BEATLES LENNON/ MCCARTNEY 8054 A HORSE WITH NO NAME AMERICA DEWEY BUNNEL 9468 A LIFE ON THE OCEAN WAVE P.D. 9469 A LITTLE MORE CIDER TOO P.D. DURITZ/BRYSON/MALLY/MIZ 8320 A LONG DECEMBER COUNTING CROWS E/GILLINGHAM/VICKREY 9112 A LOVER'S CONCERTO SARAH VAUGHAN LINZER / RANDEL 9470 A MAIDENS WISH P.D. ENGELBERT LIVRAGHI/MASON/PACE/MA 8481 A MAN WITHOUT LOVE HUMPERDINCK RIO 9183 A MILLION LOVE SONGS TAKE THAT GARY BARLOW GERRY GOFFIN/CAROLE 8073 A NATURAL WOMAN ARETHA FRANKLIN KING/JERRY WEXLER 9157 A PLACE IN THE SUN STEVIE WONDER RON MILLER/BRYAN WELLS 9471 A THOUSAND LEAGUES AWAY P.D. -

Danske Spil: Den Gamle X Factor-Trio Gendannes

2018-04-12 07:00 CEST Danske Spil: Den gamle X Factor-trio gendannes X Factor er netop blevet afsluttet på DR. Og selvom det er ganske sikkert, at programmet fortsætter på TV2, så er det stadig mere usikkert, hvem der sætter sig på de tre pladser på dommertrioen. Danske Spils oddssættere vurderer dog, at det bliver en kendt tidligere trio, der sætter sig i stolene. -Nu hvor Thomas Blachman har sagt ja til at overgå til TV2, så forestiller vi os, at hans gode kollega gennem flere sæsoner, Remee, også takker ja, siger oddsansvarlig hos Danske Spil, Peter Emmike Rasmussen, og tilføjer: - Remee har tidligere udtalt, at han ikke diskriminerer over tv-stationer. Derudover har han også udtalt, at han tror, TV2 kan gøre noget fantastisk med formatet. Vi vurderer derfor, at han er en oplagt kandidat og favorit til et sæde i dommerpanelet, hvilket odds 1,15 på Remee også indikerer. Holder oddssætternes vurdering stik er der dermed to af de tre dommerpladser besat, og mens oddssætterne vurderer det forholdsvis sandsynligt, at dommertrioen kommer til at bestå af Thomas Blachmann og Remee, så er det et lidt større spørgsmål, hvem der sætter sig i det tredje sæde. Dog er det en velkendt sangerinde, de har som favorit. -Vi vurderer, at Lina Rafn er favorit blandt kvinderne til odds 2,00. Hun har tidligere været X Factor-dommer med stor popularitet blandt seerne. En konstellation med Blachman, Remee og Lina vurderer vi er mest sandsynligt, siger Peter Emmike Rasmussen. Han vil dog ikke afvise, at det kan blive en tredje dommer, der snupper den sidste plads. -

Tal, Tendenser, Markedsstatistik Og Analyser + Artikler Om Den Danske

STATUS 2008/09: UAFHÆNGIGE SELSKABER 04 MODSÆTNINGERNES ÅR 20 UNDER DIGITALT PRES IFPI’s formand, Henrik Daldorph, ser Væksten i det digitale marked presser Tal, tendenser, markedsstatistik og tilbage på markante begivenheder for den uafhængige sektor, som i 2008 havde analyser + artikler om den danske pladebranchen i 2008 og første halvdel af tilbagegang. Vi analyserer udviklingen. pladebranche 2008/09 2009. Fra den nye oplevelseszone til dom- men i The Pirate Bay-sagen. FREELANCERE I 30 MUSIKBRANCHEN KUNSTNERNE HAR STADIG Pladebranchen omfatter hundredvis af 14 BRUG FOR ET PLADESELSKAB arbejdspladser. De senere års omfattende Interview med en af pladebranchens suc- forandringer har skabt helt nye struktu- cesfulde ledere Jakob Sørensen, direktør rer – og en lang række nye virksomheder, for Copenhagen Records. Om hvad kunst- der fungerer som underleverandører til nere skal bruge et pladeselskab til i 2009. den etablerede del af branchen. Vi ser Om manglende skarphed i branchen. Og nærmere på freelancemarkedet. om forventningerne til fremtiden. Og så får vi historien om Alphabeats internationale succes. Plus: Hitlisterne 2008 / Guld- & platincertificeringer 2008 / DMA09 og meget mere Foto: Kristian Holm PLADEBRANCHEN.08 Velkommen til Pladebranchen.08 f Vi har forud for udarbejdelsen af IFPI’s femte årsskrift I et længere interview fortæller Jakob Sørensen fra Copen- overvejet grundigt, om vi skulle kalde det noget andet end hagen Records således bl.a. om selskabets arbejde med ”Pladebranchen.08”, fordi vores medlemmer, der pt. står for en af de største, danske succeshistorier i nyere tid – Alpha- ca. 95 % af omsætningen af indspillet musik i Danmark, i beat – og om hvorfor kunstnere stadig kan have glæde stadigt højere grad beskæftiger sig med alt muligt andet end af et pladeselskab i 2009. -

Masteroppgave Torgeir Kristiansen

Forside laget av Robert Høyem, 2011 Forord Prosessen med å ferdigstille denne oppgaven har vært en veldig fin, morsom og lærerik tid. Først og fremst vil jeg takke min veileder Anne Danielsen for uvurderlig hjelp, inspirerende veiledningsmøter og grundige tilbakemeldinger. Jeg vil også rette en stor takk til Institutt for musikkvitenskap for fem fantastiske studieår. Undervisningskvaliteten og det sosiale miljøet har overskredet alle mine forventninger. Til slutt vil jeg takke Ola Håmpland og Kai Robøle for mange berikende samtaler om popmusikk, min kjære samboer Hanne Solveig Kvislen for inspirasjon, grundig språkvask og korrektur, og min familie og mine venner for støtte og oppmuntring. Oslo, 25. april 2011 Torgeir Kristiansen i ii Innhold KAPITTEL 1: INTRODUKSJON....................................................................................................................................1 Bakgrunn for valg av oppgave....................................................................................................................................1 Problemstilling, mål og avgrensning..........................................................................................................................4 TEORI OG METODE.......................................................................................................................................................6 Oppgavens gang.....................................................................................................................................................................6 -

Olly Murs Never Been Better Mp3, Flac, Wma

Olly Murs Never Been Better mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: Never Been Better Country: UK & Europe Released: 2014 Style: Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1448 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1672 mb WMA version RAR size: 1583 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 596 Other Formats: AA TTA AIFF DMF DTS MIDI MOD Tracklist Hide Credits Did You Miss Me? Arranged By [Horns] – Jason Evigan, Nick SeeleyBacking Vocals – Jacob LuttrellEngineer [Assistant] – Issaiah Tejada*Engineer [For Mix] – John 1 HanesEngineer, Instruments [All Other], Producer, Producer [Vocals], Programmed 3:16 By – Jason EviganGuitar – Pierre Luc Rioux*Mixed By – Serban GheneaProducer [Vocals, Additional] – Dan BookStrings – Nick SeeleyWritten-By – Jason Evigan, Olly Murs, Sean Douglas Wrapped Up Arranged By [Strings Transcribed By] – Pete WhitfieldArranged By [Strings], Instruments [All Other], Producer – Steve RobsonBacking Vocals – Claude KellyCello – Nick Trygstad, Simon Turner Engineer – Sam MillerEngineer 2 [Additional] – Joe Kearns, Serge NudelEngineer [For Mix] – John HanesFeaturing – 3:05 Travie McCoy*Guitar – Luke PotashnickMixed By – Serban GheneaProgrammed By [Additional] – Josh WilkinsonViolin – Paulette Bayley, Pete Whitfield, Sarah Brandwood-SpencerWritten-By – Claude Kelly, Olly Murs, Steve Robson, Travie McCoy* Beautiful To Me Acoustic Guitar, Backing Vocals, Electric Guitar, Instrumentation By [Additional], Percussion, Piano, Producer – Martin Johnson Bass – Brandon PaddockEngineer – Brandon Paddock, Kyle Moorman, Martin Johnson Engineer [Assistant] -

2018 PS Programliste Radio

Titel Formål Afrikanske stemmer: Mødet mellem Afrika og Danmark Aktualitet og debat Baglandet - Akuttelefonen er blevet rask Aktualitet og debat Baglandet - Livet efter spiseforstyrrelsen Aktualitet og debat Baglandet remix: Beskyttede rum Aktualitet og debat Baglandet remix: Rækkehus, rasteplads og natherberg - østarbejder i DK Aktualitet og debat Baglandet remix: Ulven, niqaben og ghettoen Aktualitet og debat Baglandet remix: Vilde piger Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: 1004 lærestreger Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: Cand.psych.sårbar Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: Christianias smertebarn Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: De afviste kvinder Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: De danske vinbønders ekstreme sommer Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: De gamle danskere i ghettoen Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: De positive Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: De sidste familielæger i udkanten Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: De stjæler cykler i Bording Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: Efter nedrivningen Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: En dag ad gangen Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: En dag i djøf-land Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: Færgefolket Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: Hallo det er Børnetelefonen... Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: I cannabislægens venteværelse Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: Jeg er ludoman Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: Jurastuderende bag tremmer Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: Kampen om havet Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: Kampen om rastepladsen Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: Lykke og frustration på babyhotellet Aktualitet og debat Baglandet: Lærerne -

Tíðindi Úr Føroyum Tann 24. Mars 2015 Tíðindi Til Føroyingar

Tíðindi úr Føroyum tann 24. mars 2015 Tíðindi til føroyingar uttanlanda stuðla av tí føroysku sjómanskirkjuni. Frystir í morgun 24.03.2015 - 07:06 Ansa eftir - tað er hált í morgun. Tað hevur verið kalt í nátt, og ísurin hevur lagt seg á bilrútarnar her í lýsingini. So tað kann gott taka eitt sindur longri tíð at sleppa avstað við bilinum í morgun, enn tað plagar tá tað er komið so mikið út á várið. Landsverk ávarar eisini um hálku í morgun. Veðurstøðin á Gjáarskarði máldi trý kuldastig um 7 tíðina í morgun og á Heltnini vóru tvey kuldastig. Fleiri aðra staðir vístu hitamátarnir eisini kuldastig. Soleiðis verður sagt um koyrilíkindini í morgun: Hálku fráboðan: Gjáarskarð - 06:48: Boðað verður frá hálku. Heltnin, Oyndarfjarðarvegurin - 06:48: Roknast kann við hálku. Høgareyn - 06:48: Roknast kann við hálku. Vatnsoyrar - 06:48: Roknast kann við hálku. Oyggjarvegur við Norðadalsskarð - 06:48: Roknast kann við hálku. Kaldbaksbotnur - 06:48: Roknast kann við hálku. Sund - 06:38: Roknast kann við hálku . við Velbstaðháls - 06:48: Roknast kann við hálku. Sandoy, á Brekkuni Stóru - 06:48: Roknast kann við hálku . Ørðaskarð, Fámjinsvegurin, - 06:47: Roknast kann við hálku. Porkerishálsur - 06:48: Roknast kann við hálku. Portal.fo Havsbrún-virki í Skagen miljardaumsetning Ein av størstu fyritøkunum í Skagen, og ein av heimsins størstu í heiminum av sínum slag, fiskamjølsvirkið FF Skagen (sum Havsbrún í Fuglafirði er partaeigari í, red.), hevði ein umsetning í 2014 upp á 1,6 miljardir krónur og eitt yvirskot upp á 47 miljónir krónur. Sambært nevndarformanninum Jens A. Borup, eru serliga tvær hendingar orsøkin til góða úrslitið. -

Take That I X Factor-Finalen

2011-03-07 06:24 CET Take That i X Factor-finalen Der venter således de endelige tre finalister en oplevelse af de helt store, da de som en del af showet skal optræde sammen med det legendariske boyband. "Det er jo enestående," fortæller DRs underholdningschef og X Factor- tovholder, Jan Lagermand Lundme. Begejstringen er ikke til at tage fejl af, og det er da også lidt af et scoop, der er faldet på plads: Take That skal optræde til X Factor-finalen i Parken den 25. marts. Og ikke bare skal de optræde som femkløver med tilbagevendte Robbie Williams - de skal også optræde sammen med de tre X Factor- finalister. "Der er ingen tvivl om, at det bliver et af de mest unikke øjeblikke i dansk tv- historie, når drengene fra Take That står på scenen sammen med vores finalister - det er rigtig stort," konkluderer han. Eksplosiv interesse for Take That i Danmark Interessen for Take That har været massiv siden deres gendannelse for fem år siden, og da Robbie Williams genindtrådte i gruppen sidste år, eksploderede den. De udsendte det anmelderroste udspil 'Progress' i november, og da billetterne til deres koncert i Parken den 16. juli blev sat til salg, blev de revet væk på få timer. Det udløste en ekstrakoncert dagen før den allerede planlagte, og begejstringen for Take That er således ikke til at tage fejl af. Hvem de tre heldige finalister bliver, er der ingen, der ved endnu - kun at de skal findes blandt de tilbageværende deltagere: Rasmus, Babou, Sarah, Patricia, Annelouise og Rikke & Trine.