Suiform Soundings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fabulous Original Freddy Artwork by Wiese 152

914.764.7410 Pg 22 Aleph-Bet Books - Catalogue 90 FABULOUS ORIGINAL FREDDY ARTWORK BY WIESE 152. (BROOKS,WALTER). FREDDY THE PIG ORIGINAL ART. Offered here is RARE BROWN TITLE an original pen and ink drawing by Wiese that appears on page 19 of Wiggins for AS GOLDEN MACDONALD President (later re-issued as Freddy the Politician). The image measures 8” wide 156. [BROWN,MARGARET WISE]. BIG x 12.5” high mounted on board and is signed. The caption is on the mount and DOG LITTLE DOG by Golden Macdonald. reads” Good morning , Sir, What can we do for you?” Depicted are John Quincy Garden City: Doub. Doran (1943). 4to Adam and Jinx along with the hatted horse and they are addressing a bearded (9 1/4” square), cloth, Fine in dust wrapper man in a hat. Original Freddy work is rare. $2400.00 with some closed edge tears. 1st ed.. The story of 2 Kerry Blue terriers, written by Brown using her Golden Macdonald pseudonym. Illustrated by Leonard Weisgard and printed in the Kerry Blue color of the real dogs. One of her rarest titles. $450.00 LEONARD WEISGARD ILLUSTRATIONS 157. BROWN,MARGARET WISE. GOLDEN BUNNY. NY: Simon & Schuster (1953). Folio, glazed pictorial. boards, cover rubbed else VG. 1st ed. The title story plus 17 other stories and poems by Brown, illustrated by LEONARD WEISGARD with fabulous rich, full page color illustrations covering every page. A Big Golden Book. $200.00 158. BROWN,PAUL. HI GUY THE CINDERELLA HORSE. NY: Scribner (1944 A). 4to, cloth, Fine in sl. worn dust wrapper. -

The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research

Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Edited by Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham Chapters written in honour of Professor Colin P Groves Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Taxonomic tapestries : the threads of evolutionary, behavioural and conservation research / Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham, editors. ISBN: 9781925022360 (paperback) 9781925022377 (ebook) Subjects: Biology--Classification. Biology--Philosophy. Human ecology--Research. Coexistence of species--Research. Evolution (Biology)--Research. Taxonomists. Other Creators/Contributors: Behie, Alison M., editor. Oxenham, Marc F., editor. Dewey Number: 578.012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph courtesy of Hajarimanitra Rambeloarivony Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents List of Contributors . .vii List of Figures and Tables . ix PART I 1. The Groves effect: 50 years of influence on behaviour, evolution and conservation research . 3 Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham PART II 2 . Characterisation of the endemic Sulawesi Lenomys meyeri (Muridae, Murinae) and the description of a new species of Lenomys . 13 Guy G Musser 3 . Gibbons and hominoid ancestry . 51 Peter Andrews and Richard J Johnson 4 . -

December 28,1881

PORTLAND Τ) A i l -Y ESTABLISHED JUNE 23. 1862—VOL. 22. THURSDAY flHVV&Bl) A8 UQOni PORTLAND, MORNING, DECEMBER 25, 1884. CI λββ MAIL MATTB&f PRICE THREE CENTS. KPEC1AL NOTIfBN. mvmv if f'i.Am κ·* t*. THE PORTLAND DAILÎ PRESS, MRS. STONE'S WILL·. end Cohen was In the vesti- progress Manager NEAR THE NORTH POLE. Land also graced oar table; bat I will let car History of Gloves. Published eyery day (Sundays excepted) by the bule·, wan rushed upon by Majhew, who mean speak for itself: had returned armed. a PORTLAND PUBLISHING COMPANY, Meybew throat keen FORT CONGER, GRINNELL LAND. [Harper*· Baaar. knife Into Cohen's rlba, and the latter now At 87 Exchange Street. Portland, Me. Testimony on Both Sides All In. Eow the Arctic Christmas Dinner, 188]. Gloves do not. appear to bave been worn lu FOSTERS Sale liea at the point of death, while Mayhew )l in Explorers Spent Special TiKMa:Klght Dollars a Tear. To mall subeorlb- BOUT. before England tbe end of the 10th or be- -OF- ere, SeTOD Dollar· a Tear, 11 paid in advauoe. jail. Christmas. of Mock Turtle. of Rates Advertising: One Inch of spaoe, the AKCirnENT OF COPN«EL· FOR CON- ginning the 11th century, and the manu- FOREST CITY DYE length of oolnmn, or twelre lines nonpareil consti- MA8SACH USETTS. FISH. facture would HOUSE, tutes a TESTANTS. appear at that "square." Salmon a la period special· 13 PREBLE STREET. CHILDREN'S AND first a Good Dinner and Paieocrystic. BOYS' $1.60 per square, dally week; 76 cents per A Novel Scheme. -

Good Foundations Academy Reading and Literacy Policy

Building Knowledge and Character GOOD FOUNDATIONS ACADEMY READING AND LITERACY POLICY PURPOSE AND PHILOSOPHY The development of literacy is one of the primary aims and focuses of effort at GFA. This includes a great deal of reading from a variety of both fiction and non-fiction primary literature. Particularly in the early grades, GFA emphasizes reading and more reading. Most American schools dedicate two or more hours each day to “literacy.” A majority of time is spent teaching children the fundamentals of reading strategies, such as making inferences, predicting, classifying, and looking for the main idea. The purpose of these exercises is to bolster test scores, independent of real knowledge. In contrast, GFA strives to develop the appreciation of language, increase specific knowledge, and provide meaning to students through the achievement of Primary Literacy, Mature Literacy, and Moral Literacy. Primary Literacy Primary Literacy begins with phonic recognition. Our goal in the early grades is for students to receive explicit, systematic phonemic awareness and phonics instruction. Children are provided deliberate, coherent, direct instruction in letter-sound correspondences. Practices which teach children to rely on word-memorization (the look-say method) and guessing (through illustration and/or context) are avoided. Once phonetic decoding skills are introduced, fluency must be developed. Fluency allows students to focus their mental energies on comprehension rather than decoding. Fluency means “flowing,” and in this context it also means “fast.” Fluency takes practice - a lot of it. Riggs & Open Court Phonics, selected stories from Open Court, and selected books from Accelerated Reader (AR) are the primary sources for the development of decoding skills and fluency at GFA. -

THE FREDDY the PIG SERIES by Walter R. Brooks Illustrated by Kurt Wiese

THE FREDDY THE PIG SERIES by Walter R. Brooks illustrated by Kurt Wiese Introduction With the 1927 publication of To and Again (later re-titled Freddy Goes to Florida), Walter R. Brooks began a series that would ultimately stretch to twenty-six volumes and become a classic of 20th century American children's literature. Especially memorable for the richness of their characterizations, the books about the pig nonpareil and his many friends are also unforgettable celebrations of the value of friendship and the practical virtues of loyalty, steadfastness, kindness, and simply doing the right thing. Always inventive in their plotting, satisfying in the authenticity of their rural and small town settings, filled with memorable phrases and homely wisdom, the Freddy books capture the same kind of American spirit as do the Homer Price books by Robert McCloskey, E.B. White's Charlotte's Web, and Robert Lawson's Ben and Me and Rabbit Hill. Like these other masters, Brooks never underestimated or wrote down to his readers. His respect for them is reflected in the richness of his language and the thoughtfulness of his themes. Most importantly, perhaps, his are among the very first enduringly significant humorous children's books of the 20th century. And they contain the best kind of humor, still fresh and relevant to today's readers; it arises naturally out of character and incongruity, is embellished with wonderfully inventive and witty word play, and is never mean or hurtful. It springs from both the mind AND the heart, a reason the Freddy books are universally beloved by readers of all ages. -

Social-Ecological Resilience in the Viking-Age to Early-Medieval Faroe Islands

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 Social-Ecological Resilience in the Viking-Age to Early-Medieval Faroe Islands Seth Brewington Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/870 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SOCIAL-ECOLOGICAL RESILIENCE IN THE VIKING-AGE TO EARLY-MEDIEVAL FAROE ISLANDS by SETH D. BREWINGTON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 © 2015 SETH D. BREWINGTON All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Anthropology to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _Thomas H. McGovern__________________________________ ____________________ _____________________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _Gerald Creed_________________________________________ ____________________ _____________________________________________________ Date Executive Officer _Andrew J. Dugmore____________________________________ _Sophia Perdikaris______________________________________ _George Hambrecht_____________________________________ -

The Global Impact of Wild Pigs (Sus Scrofa) on Terrestrial Biodiversity Derek R

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The global impact of wild pigs (Sus scrofa) on terrestrial biodiversity Derek R. Risch1*, Jeremy Ringma1,2 & Melissa R. Price1 The International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species is a comprehensive database of over 120,000 species and is a powerful tool to evaluate the threat of invasive species to global biodiversity. Several problematic species have gained global recognition due to comprehensive threat assessments quantifying the threat these species pose to biodiversity using large datasets like the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. However, the global threat of wild pigs (Sus scrofa) to biodiversity is still poorly understood despite well-documented ecosystem level impacts. In this study, we utilized the IUCN Red List to quantify the impacts of this globally distributed species throughout its native and non-native range. Here we show that wild pigs threaten 672 taxa in 54 diferent countries across the globe. Most of these taxa are listed as critically endangered or endangered and 14 species have been driven to extinction as a direct result of impacts from wild pigs. Our results show that threats from wild pigs are pervasive across taxonomic groups and that island endemics and taxa throughout the non-native range of wild pigs are particularly vulnerable. Global biodiversity is decreasing at an alarming rate with species extinction rates 1000 times greater than natu- ral background rates and anticipated to be 10,000 times greater in the future 1. Te establishment and spread of invasive species are among the primary drivers of these losses as they directly afect native species and can infuence ecosystem change through disturbance 2–4. -

Declining Populations of the Javan Warty Pig Sus Verrucosus

Oryx Vol 40 No 1 January 2006 Declining populations of the Javan warty pig Sus verrucosus Gono Semiadi and Erik Meijaard Abstract We conducted an interview-based survey for hunting pressure. Competition from and hybridization the Javan warty pig Sus verrucosus, endemic to the islands with the Eurasian wild boar Sus scrofa may be further of Java and Bawean in Indonesia. The species occurs threats to S. verrucosus. Rapid action is needed to prevent in 10 isolated areas, although some additional, probably extinction in the wild. We recommend effective pro- very small populations, may remain. Compared to a tection of selected S. verrucosus populations, lobbying survey conducted in 1982, 17 of the 32 (53%) populations of the Government to give protected status to S. verru- are extinct or have dropped to levels so low that local cosus, conducting ecological research and investigating hunters have failed to encounter the species in recent crop damage issues, and establishment of conservation years. This indicates a rapid population decline. We breeding programmes. hypothesize that this loss is primarily caused by a decline in suitable habitat, especially stands of teak Tectona Keywords Ethnobiology, Indonesia, Javan warty pig, grandis forest or similar forest plantations, and by high Suidae, survey, Sus verrucosus, teak. Introduction extinct. Blouch found that S. verrucosus occurred in lowland areas below 800 m, although there are several The Javan warty pig Sus verrucosus is endemic to the museum specimens of S. verrucosus from localities as islands of Java and Bawean in Indonesia. Hardjasamita high as 1,500 m (van Strien, 2001). Its preferred habitat (1987) traced its ancestry to several fossil pig species of consisted of extensive areas of lowland secondary veg- Java and this, together with phylogenetic data (Randi etation, particularly teak Tectona grandis plantations in et al., 1996), suggests isolation on Java for c. -

Records of Small Carnivores and of Medium-Sized Nocturnal Mammals on Java, Indonesia

Records of small carnivores and of medium-sized nocturnal mammals on Java, Indonesia E. J. RODE-MARGONO1*, A. VOSKAMP2, D. SPAAN1, J. K. LEHTINEN1, P. D. ROBERTS1, V. NIJMAN1 and K. A. I. NEKARIS1 Abstract Most small carnivores and nocturnal mammals in general on the Indonesian island of Java lack frequent and comprehensive dis- tribution surveys. Nocturnal surveys by direct observations from walked transects (survey effort 127 km, about 254 hours) and trap-nights) and direct sightings from Cipaganti, western Java, from two years’ research presence, yielded records of Leopard Cat Prionailurus bengalensis (121 encounters/2 sites), Javan Mongoose Herpestes javanicus (4/2), Yellow-throated Marten Mar- (1/1), Javan Ferret Badger Melogale orientalis (37/1), Banded Linsang Prionodon linsang (2/2), Binturong Arctictis binturong (3/2), Common Palm Civet Paradoxurus hermaphroditus (145/10), Small Indian Civet Viverricula indica (8/1), Javan Chevrotain Tragulus javanicus (3/2), Javan Colugo Galeopterus variegatus (24/5), Spotted Giant Flying Squirrel Petaurista el- egans (2/1) and Red Giant Flying Squirrel P. petaurista (13/3), as well as of the research’s focus, Javan Slow Loris Nycticebus javanicus Small-toothed Palm Civet Arctogalidia trivirgata, Sunda Stink-badger Mydaus javanensis and Sunda Porcupine Hystrix javanica - sites. We report descriptive data on behaviour, ecology and sighting distances from human settlements. Regional population of the survey sites presented here would allow for more intensive studies of several species. Keywords: Arctogalidia trivirgataGaleopterus variegatus, Hystrix javanica, Javan Colugo, nocturnal mammals, Small-toothed Palm Civet, spotlighting, Sunda Porcupine Pengamatan hewan karnivora kecil dan mamalia nokturnal berukuran sedang di Jawa, Indonesia Abstrak Sebagian besar dari Ordo karnivora kecil dan mamalia nokturnal di Pulau Jawa, Indonesia kurang memiliki survey distribusi yang komprehensif. -

2012 Annual Report Conservation Science 1 TABLE of CONTENTS

2012 Annual Report conservation science 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Introduction 5 BACK FROM THE BRINK Blue Iguanas 8 SCIENCE SAVES SPECIES 10 FIELD CONSERVATION PROJECTS — International 13 RESTORING A FRESHWATER NATIVE Southern Appalachian Brook Trout 15 FIELD CONSERVATION PROJECTS — United States 56 A DISEASE-FREE FUTURE FOR ETHIOPIAN WOLVES A Wolf Vaccine in Sheep’s Clothing 58 JAVAN WARTY PIG Conservation and Recovery Cover Photo: Attwater’s Prairie Chicken © Stephanie Adams, Houston Zoo INTRODUCTION The 2012 Annual Report on Conservation Science Zoos and aquariums accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) serve as conservation centers that are concerned about ecosystem health, take responsibility for species survival, contribute to research, conservation, and education, and provide communities the opportunity to develop personal connections with the animals in their care. Whether breeding and reintroducing endangered species; rescuing, rehabilitating, and releasing sick and injured animals; maintaining far-reaching educational and outreach programs; or supporting and conducting in-situ and ex-situ research and field conservation projects, accredited zoos and aquariums play a vital role in maintaining our planet’s diverse wildlife and natural habitats while engaging the public to appreciate and participate in conservation. The 2012 Annual Report on Conservation Science (ARCS) focuses exclusively on those conservation projects that have a direct impact on animals in the wild. The report is based on survey data submitted by 179 of AZA’s 223 accredited zoos and aquariums and 15 certified- related facilities. Each of the more than 2,700 project submissions listed in this report were reviewed by at least one member of AZA’s Field Conservation Committee (FCC) to ensure that the project met the criteria of having a direct impact on animals in the wild. -

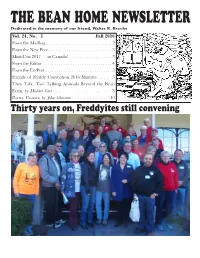

THE BEAN HOME NEWSLETTER Dedicated to the Memory of Our Friend, Walter R

THE BEAN HOME NEWSLETTER Dedicated to the memory of our friend, Walter R. Brooks Vol. 24, No. 1 Fall 2016 From the Mailbag . 2 From the New Prez . 3 Mini-Con 2017 — in Canada! . 3 From the Editor . 4 From the Ex-Prez . 5 Friends of Freddy Convention 2016 Minutes . 5 They Talk, Too! Talking Animals Beyond the Bean Farm, by Michael Cart . 8 Poetry Corner, by John Chastain . 10 Thirty years on, Freddyites still convening From the Mailbag Thank you very much for the newsletter. My wife and I have been Freddy fans since elementary school. This fall I’ll turn 70, and my enthusiasm for the works of Walter R. Brooks is undimmed. The Friends of Freddy group means a great deal to me, even though I never have been able to attend the convention. Ron Keffer (Homer, AK) Member since June 1995 Once again my day is brightened by the entrance of our dear old friends from Beanlandia! WIGGINS FOR PRESIDENT—sounds so much sweeter than—well—nothing more needs to be said...! Except: Keep on keeping on! Gratefully, Jane Roosen (Mesa, AZ) Member since August 2004 These are carolers in Centerboro. Freddy took the picture for the Bean Home News. The dog is chasing Jinx. Mrs. Wiggins is singing lustily but off-key. Simon and his family have greedily eaten most of the peanut butter and sunflower seeds from the pine cone ornaments made by school children. Mrs. Bean and her friends have hot cocoa and cookies waiting for the carolers and others attending, on the tailgate of a pick-up truck at the edge of the green. -

View Complete in Context #37 As

In Context Number 37 Spring 2017 The Newsletter of The Nature Institute Letter to Our Readers 2 NOTES AND REVIEWS Children and Nature / George K. Russell 3 NEWS FROM THE INSTITUTE 2017 Farmers Course 8 Our New Fellowship Program 9 Mathematics Alive! 10 Out and About 10 A New Colleague 11 New Online Resources 11 New Publications 12 A Challenge Grant 12 Thank You! 13 FEATURE ARTICLES What Is Life? / Stephen L. Talbott 14 Why Does a Zebra Have Stripes? / Craig Holdrege 17 # 37 Dear Friends, The Nature Institute Ours has been called an “age of abstraction.” We learn, early in our education, to ab-stract (“pull out”) from every rich, phenomenal context particular parts or STAFF aspects—especially those parts or aspects that lend themselves to mathematical Linda Bolluyt treatment. The almost inevitable temptation is then to allow our abstractions to Colleen Cordes stand in the place of the original phenomena, which then may be easily forgotten. Bruno Follador And so, atoms and molecules substitute for mountains and rainbows, wavelengths Craig Holdrege substitute for color, and genes substitute for organisms. It is not surprising that Henrike Holdrege Seth Jordan distorted understandings and policies result when we ignore a many-sided reality in Veronica Madey favor of one-dimensional abstractions serving the purposes of mathematical theory Stephen L. Talbott and technological manipulation. Adjunct Researchers/Faculty In this issue of In Context, we present three articles that deal in one way or Jon McAlice another with the limitations of abstraction and how to overcome them. To begin Marisha Plotnik Vladislav Rozentuller with, George Russell asks how we can restore to children an essential and healthy Nathaniel Williams relation to the natural world—this at a time when, for many children, their primary Johannes Wirz exposure to nature is mediated by that most severe tool of abstraction, the electronic Board of Directors screen.