2012 Annual Report Conservation Science 1 TABLE of CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

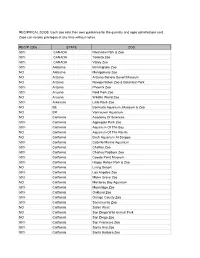

Reciprocal List (Updated 0 9 /22 / 2 0 2 0) Membership Department (941) 388-4441, Ext

Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium - Reciprocal List (Updated 0 9 /22 / 2 0 2 0) Membership Department (941) 388-4441, Ext. 373 STATE CITY INSTITUTION RECIPROCITY Canada Calgary - Alberta Calgary Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Canada Quebec - Granby Granby Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Canada Toronto Toronto Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Canada Winnipeg Assiniboine Park Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Mexico Leon Parque Zoologico de Leon 50% Off Admission Tickets Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Alaska Seward Alaska Sealife Center 50% Off Admission Tickets Arizona Phoenix The Phoenix Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Arizona Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% Off Admission Tickets Arizona Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Oakland Oakland Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Palm Desert The Living Desert 50% Off Admission Tickets California Sacramento Sacramento Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Francisco San Francisco Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Jose Happy Hollow Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Mateo CuriOdyssey 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Pedro Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% Off Admission Tickets California Santa Barbara Santa Barbara Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium - Reciprocal List (Updated 0 9 /22 / 2 0 2 0) Membership Department (941) 388-4441, Ext. -

The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research

Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Edited by Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham Chapters written in honour of Professor Colin P Groves Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Taxonomic tapestries : the threads of evolutionary, behavioural and conservation research / Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham, editors. ISBN: 9781925022360 (paperback) 9781925022377 (ebook) Subjects: Biology--Classification. Biology--Philosophy. Human ecology--Research. Coexistence of species--Research. Evolution (Biology)--Research. Taxonomists. Other Creators/Contributors: Behie, Alison M., editor. Oxenham, Marc F., editor. Dewey Number: 578.012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph courtesy of Hajarimanitra Rambeloarivony Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents List of Contributors . .vii List of Figures and Tables . ix PART I 1. The Groves effect: 50 years of influence on behaviour, evolution and conservation research . 3 Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham PART II 2 . Characterisation of the endemic Sulawesi Lenomys meyeri (Muridae, Murinae) and the description of a new species of Lenomys . 13 Guy G Musser 3 . Gibbons and hominoid ancestry . 51 Peter Andrews and Richard J Johnson 4 . -

Syllabus SCI 1

Kingsborough Community College The City University of New York College Now - Syllabus SCI 1: Issues and Adventures in Science - 3 credits, 3 hours Course Coordinator: Dr. Mary Ortiz Course Description: Science 1 explores scientific issues through integration of concepts and techniques from the biological, physical and health sciences. Issues examined include humankind's place in the universe, in which the structure and origin of the universe, solar system, Earth and life are considered; humankind's attempts at mastery of the world, which focuses on space and undersea exploration, genetics research and engineering, bio/computer technology and energy/pollution challenges; and humankind's development of self-knowledge as studied through research on aging, the human mind, fertility, immunity, nutrition and alternative medicine. Catalog Description: SCI 100 ISSUES AND ADVENTURES IN SCIENCE (3 crs. 3 hrs.) The most recent and important discoveries in the biological and physical sciences are presented,observed, discussed, and experimented with, to acquaint students with the world around them. Brain research, studies of aging, disease, fertility, immunity,and the origin of life are explored. Studies emphasize relations to mankind's place in the universe, selfexplorations and technological achievements. Prerequisite: Enrollment in "College Now" Program Flexible Core: Scientific World (Group E) College Now Description: Students study concepts and methodologies used to investigate issues dominating current thought in physical, biological and health sciences. Topic examples include brain research, sleep, aging, fertility, immunity, extinction, pollution and disease. Course Rationale: Most college-level science courses involve in-depth study of details of specific disciplines (e.g., genetics) within the biological and physical sciences. -

Chacoan Peccary

Chacoan Peccary Chacoan Peccary Catagonus wagneri conservation strategy Mariana Altrichter1,2, Arnaud Desbiez3, Harald Beck1,4, Alberto Yanosky5, Juan Campos6 1chairs IUCN Peccary Specialist Group, 2Prescott College, 3Royal Zoological Society of Scotland and IUCN SSC CBSG Brazil, 4Towson University, 5Guyra Paraguay, 6Tagua Project field coordinator, Paraguay Summary The Chacoan peccary (Catagonus wagneri), an endemic species of the Gran Chaco ecoregion, is endangered of extinction due mainly to habitat loss and hunting. The only conservation plan for the species was written in 1993. Because the situation continues deteriorating, and the rate of deforestation in the region is currently among the highest in the world, the IUCN SSC Peccary Specialist group saw the need to develop a new conservation strategy. A workshop was held in Paraguay, in March 2016, with representatives of different sectors and range countries. This paper presents a summary of the problems, threats and actions identified by the participants. The other two results of the workshop, a species distribution and population viability modeling, are presented separately in this same newsletter issue. Introduction The Chacoan peccary (Catagonus wagneri) or Taguá, as it is called in Paraguay, is an endemic and endangered species that inhabits the thorn forests of the Gran Chaco of Bolivia, Paraguay, and Argentina. The Gran Chaco is the second largest ecoregion in South America after the Amazonia. The species is listed as endangered by the IUCN Red List and in CITES I Appendix (IUCN 2016). In 1993, the entire Chacoan peccary population was estimated to be less than 5000 individuals (Taber, 1991 et al. 1993, 1994) and it has been declining since then (Altrichter & Boaglio, 2004). -

Green Space and Mortality Following Ischemic Stroke

Environmental Research 133 (2014) 42–48 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Environmental Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envres Green space and mortality following ischemic stroke Elissa H. Wilker a,b,n, Chih-Da Wu b,c, Eileen McNeely b, Elizabeth Mostofsky a, John Spengler b, Gregory A. Wellenius d, Murray A. Mittleman a,b a Cardiovascular Epidemiology Research Unit, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA 02215 USA b Department of Environmental Health, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA c Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, College of Agriculture, National Chiayi University, Chiayi, Taiwan d Department of Epidemiology, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA article info abstract Article history: Background: Residential proximity to green space has been associated with physical and mental health Received 30 January 2014 benefits, but whether green space is associated with post-stroke survival has not been studied. Received in revised form Methods: Patients Z21 years of age admitted to the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) 2 May 2014 between 1999 and 2008 with acute ischemic stroke were identified. Demographics, presenting Accepted 4 May 2014 symptoms, medical history and imaging results were abstracted from medical records at the time of Available online 4 June 2014 hospitalization for stroke onset. Addresses were linked to average Normalized Difference Vegetation Keywords: Index, distance to roadways with more than 10,000 cars/day, and US census block group. Deaths were Mortality identified through June 2012 using the Social Security Death Index. Green space Results: There were 929 deaths among 1645 patients with complete data (median follow up: 5 years). -

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List – Updated July 1, 2021 The following AZA-accredited institutions have agreed to offer a 50% discount on admission to visiting Santa Barbara Zoo Members who present a current membership card and valid picture ID at the entrance. Please note: Each participating zoo or aquarium may treat membership categories, parking fees, guest privileges, and additional benefits differently. Reciprocation policies subject to change without notice. Please call to confirm before you visit. Iowa Rosamond Gifford Zoo at Burnet Park - Syracuse Alabama Blank Park Zoo - Des Moines Seneca Park Zoo – Rochester Birmingham Zoo - Birmingham National Mississippi River Museum & Aquarium - Staten Island Zoo - Staten Island Alaska Dubuque Trevor Zoo - Millbrook Alaska SeaLife Center - Seaward Kansas Utica Zoo - Utica Arizona The David Traylor Zoo of Emporia - Emporia North Carolina Phoenix Zoo - Phoenix Hutchinson Zoo - Hutchinson Greensboro Science Center - Greensboro Reid Park Zoo - Tucson Lee Richardson Zoo - Garden Museum of Life and Science - Durham Sea Life Arizona Aquarium - Tempe City N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher - Kure Beach Arkansas Rolling Hills Zoo - Salina N.C. Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores - Atlantic Beach Little Rock Zoo - Little Rock Sedgwick County Zoo - Wichita N.C. Aquarium on Roanoke Island - Manteo California Sunset Zoo - Manhattan Topeka North Carolina Zoological Park - Asheboro Aquarium of the Bay - San Francisco Zoological Park - Topeka Western N.C. (WNC) Nature Center – Asheville Cabrillo Marine Aquarium -

Home Range and Spatial Organization by the Hoary Fox Lycalopex Vetulus (Mammalia: Carnivora: Canidae): Response to Social Disruption of Two Neighboring Pairs

OPEN ACCESS The Journal of Threatened Taxa is dedicated to building evidence for conservaton globally by publishing peer-reviewed artcles online every month at a reasonably rapid rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org. All artcles published in JoTT are registered under Creatve Commons Atributon 4.0 Internatonal License unless otherwise mentoned. JoTT allows unrestricted use of artcles in any medium, reproducton, and distributon by providing adequate credit to the authors and the source of publicaton. Journal of Threatened Taxa Building evidence for conservaton globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Communication Home range and spatial organization by the Hoary Fox Lycalopex vetulus (Mammalia: Carnivora: Canidae): response to social disruption of two neighboring pairs Julio C. Dalponte, Herson S. Lima, Stuart Klorfne & Nelton C. da Luz 26 May 2018 | Vol. 10 | No. 6 | Pages: 11703–11709 10.11609/jot.3082.10.6.11703-11709 For Focus, Scope, Aims, Policies and Guidelines visit htp://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-0 For Artcle Submission Guidelines visit htp://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/submissions#onlineSubmissions For Policies against Scientfc Misconduct visit htp://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-2 For reprints contact <[email protected]> Publisher & Host Partners Member Threatened Taxa Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 May 2018 | 10(6): 11703–11709 Home range and spatial organization by the Hoary Fox Lycalopex vetulus (Mammalia: Carnivora: Canidae): response Communication to social disruption of two neighboring pairs ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Julio C. Dalponte 1, Herson S. Lima 2, Stuart Klorfne 3 & Nelton C. -

Regional Differences in Wild North American River Otter (Lontra Canadensis) Behavior and Communication

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 2020 Regional Differences in Wild North American River Otter (Lontra canadensis) Behavior and Communication Sarah Walkley Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Biological Psychology Commons, Cognitive Psychology Commons, Comparative Psychology Commons, Integrative Biology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Walkley, Sarah, "Regional Differences in Wild North American River Otter (Lontra canadensis) Behavior and Communication" (2020). Dissertations. 1752. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1752 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REGIONAL DIFFERENCES IN WILD NORTH AMERICAN RIVER OTTER (LONTRA CANADENSIS) BEHAVIOR AND COMMUNICATION by Sarah N. Walkley A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Education and Human Sciences and the School of Psychology at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by: Dr. Hans Stadthagen, Committee Chair Dr. Heidi Lyn Dr. Richard Mohn Dr. Carla Almonte ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Hans Stadthagen Dr. Sara Jordan Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Director of School Dean of the Graduate School May 2020 COPYRIGHT BY Sarah N. Walkley 2020 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT This study focuses on the vocalization repertoires of wild North American river otters (Lontra canadensis) in New York and California. Although they are the same species, these two established populations of river otters are separated by a significant distance and are distinct from one another. -

2006 Reciprocal List

RECIPRICAL ZOOS. Each zoo sets their own guidelines for the quantity and ages admitted per card. Zoos can revoke privileges at any time without notice. RECIP 2006 STATE ZOO 50% CANADA Riverview Park & Zoo 50% CANADA Toronto Zoo 50% CANADA Valley Zoo 50% Alabama Birmingham Zoo NO Alabama Montgomery Zoo NO Arizona Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum NO Arizona Navajo Nation Zoo & Botanical Park 50% Arizona Phoenix Zoo 50% Arizona Reid Park Zoo NO Arizona Wildlife World Zoo 50% Arkansas Little Rock Zoo NO BE Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo NO BR Vancouver Aquarium NO California Academy Of Sciences 50% California Applegate Park Zoo 50% California Aquarium Of The Bay NO California Aquarium Of The Pacific NO California Birch Aquarium At Scripps 50% California Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% California Chaffee Zoo 50% California Charles Paddock Zoo 50% California Coyote Point Museum 50% California Happy Hollow Park & Zoo NO California Living Desert 50% California Los Angeles Zoo 50% California Micke Grove Zoo NO California Monterey Bay Aquarium 50% California Moonridge Zoo 50% California Oakland Zoo 50% California Orange County Zoo 50% California Sacramento Zoo NO California Safari West NO California San Diego Wild Animal Park NO California San Diego Zoo 50% California San Francisco Zoo 50% California Santa Ana Zoo 50% California Santa Barbara Zoo NO California Seaworld San Diego 50% California Sequoia Park Zoo NO California Six Flags Marine World NO California Steinhart Aquarium NO CANADA Calgary Zoo 50% Colorado Butterfly Pavilion NO Colorado Cheyenne -

The 2008 IUCN Red Listings of the World's Small Carnivores

The 2008 IUCN red listings of the world’s small carnivores Jan SCHIPPER¹*, Michael HOFFMANN¹, J. W. DUCKWORTH² and James CONROY³ Abstract The global conservation status of all the world’s mammals was assessed for the 2008 IUCN Red List. Of the 165 species of small carni- vores recognised during the process, two are Extinct (EX), one is Critically Endangered (CR), ten are Endangered (EN), 22 Vulnerable (VU), ten Near Threatened (NT), 15 Data Deficient (DD) and 105 Least Concern. Thus, 22% of the species for which a category was assigned other than DD were assessed as threatened (i.e. CR, EN or VU), as against 25% for mammals as a whole. Among otters, seven (58%) of the 12 species for which a category was assigned were identified as threatened. This reflects their attachment to rivers and other waterbodies, and heavy trade-driven hunting. The IUCN Red List species accounts are living documents to be updated annually, and further information to refine listings is welcome. Keywords: conservation status, Critically Endangered, Data Deficient, Endangered, Extinct, global threat listing, Least Concern, Near Threatened, Vulnerable Introduction dae (skunks and stink-badgers; 12), Mustelidae (weasels, martens, otters, badgers and allies; 59), Nandiniidae (African Palm-civet The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is the most authorita- Nandinia binotata; one), Prionodontidae ([Asian] linsangs; two), tive resource currently available on the conservation status of the Procyonidae (raccoons, coatis and allies; 14), and Viverridae (civ- world’s biodiversity. In recent years, the overall number of spe- ets, including oyans [= ‘African linsangs’]; 33). The data reported cies included on the IUCN Red List has grown rapidly, largely as on herein are freely and publicly available via the 2008 IUCN Red a result of ongoing global assessment initiatives that have helped List website (www.iucnredlist.org/mammals). -

The Role of the US Captive Tiger Population in the Trade in Tiger Parts

PAPER TIGERS? The Role of the U.S. Captive Tiger Population in the Trade in Tiger Parts Douglas F. Williamson & Leigh A. Henry A TRAFFIC NORTH AMERICA REPORT This report was published with the kind support of PAPER TIGERS? The Role of the U.S. Captive Tiger Population in the Trade in Tiger Parts Douglas F. Williamson and Leigh A. Henry July 2008 TRAFFIC North America World Wildlife Fund 1250 24th Street NW Washington, DC 20037 USA Visit www.traffic.org for an electronic edition of this report, and for more information about TRAFFIC North America. © 2008 WWF. All rights reserved by World Wildlife Fund, Inc. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction, in full or in part, of this publication must credit TRAFFIC North America. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, World Wildlife Fund (WWF), or IUCN-International Union for Conservation of Nature. The designation of geographic entities in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership are held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint program of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Williamson, D.F. and L.A. Henry. 2008. Paper Tigers?: The Role of the U.S. Captive Tiger Population in the Trade in Tiger Parts . -

North American Zoos with Mustelid Exhibits

North American Zoos with Mustelid Exhibits List created by © birdsandbats on www.zoochat.com. Last Updated: 19/08/2019 African Clawless Otter (2 holders) Metro Richmond Zoo San Diego Zoo American Badger (34 holders) Alameda Park Zoo Amarillo Zoo America's Teaching Zoo Bear Den Zoo Big Bear Alpine Zoo Boulder Ridge Wild Animal Park British Columbia Wildlife Park California Living Museum DeYoung Family Zoo GarLyn Zoo Great Vancouver Zoo Henry Vilas Zoo High Desert Museum Hutchinson Zoo 1 Los Angeles Zoo & Botanical Gardens Northeastern Wisconsin Zoo & Adventure Park MacKensie Center Maryland Zoo in Baltimore Milwaukee County Zoo Niabi Zoo Northwest Trek Wildlife Park Pocatello Zoo Safari Niagara Saskatoon Forestry Farm and Zoo Shalom Wildlife Zoo Space Farms Zoo & Museum Special Memories Zoo The Living Desert Zoo & Gardens Timbavati Wildlife Park Turtle Bay Exploration Park Wildlife World Zoo & Aquarium Zollman Zoo American Marten (3 holders) Ecomuseum Zoo Salomonier Nature Park (atrata) ZooAmerica (2.1) 2 American Mink (10 holders) Bay Beach Wildlife Sanctuary Bear Den Zoo Georgia Sea Turtle Center Parc Safari San Antonio Zoo Sanders County Wildlife Conservation Center Shalom Wildlife Zoo Wild Wonders Wildlife Park Zoo in Forest Park and Education Center Zoo Montana Asian Small-clawed Otter (38 holders) Audubon Zoo Bright's Zoo Bronx Zoo Brookfield Zoo Cleveland Metroparks Zoo Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Dallas Zoo Denver Zoo Disney's Animal Kingdom Greensboro Science Center Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens 3 Kansas City Zoo Houston Zoo Indianapolis