Read the Report from Our Workshop at the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Langue Catégorie Chaine Qualité • Cinéma DE • Allemagne Cinéma

Langue Catégorie Chaine Qualité •●★ Cinéma DE ★●• Allemagne Cinéma Family TV FHD HD Allemagne Cinéma Kinowelt HD Allemagne Cinéma MGM FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY ATLANTIC (FHD) FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA (FHD) FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA 1 (FHD) FHD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Cinema 24 FHD HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Cinema 24 HD HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA ACTION FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA ACTION (FHD) FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA FAMILY (FHD) HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Cinema HD FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA HITS (FHD) HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY EMOTION HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Hits HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Hits HD HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Krimi HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Nostalgie HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 1 HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 2 HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 3 HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 4 HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 5 HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 6 •●★ Culture DE ★●• Allemagne Culture 3SAT HD Allemagne Culture A & E HD Allemagne Culture Animal Planet HD HD Allemagne Culture DISCOVERY HD HD Allemagne Culture Goldstar TV HD Allemagne Culture Nat Geo Wild HD Allemagne Culture Sky Dmax HD HD Allemagne Culture Spiegel Geschichte HD Allemagne Culture SWR Event 1 HD Allemagne Culture SWR Event 3 HD Allemagne Culture Tele 5 HD HD Allemagne Culture WDR Event 4 •●★ Divertissement DE ★●• Allemagne Divertissement13TH STREET FHD Allemagne Divertissement13TH STREET (FHD) HD Allemagne DivertissementA&E HD Allemagne DivertissementAustria 24 TV HD Allemagne DivertissementComedy Central / VIVA AT HD Allemagne DivertissementDMAX -

San Diego Public Library New Additions October 2008

San Diego Public Library New Additions October 2008 Juvenile Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities Compact Discs 100 - Philosophy & Psychology DVD Videos/Videocassettes 200 - Religion E Audiocassettes 300 - Social Sciences E Audiovisual Materials 400 - Language E Books 500 - Science E CD-ROMs 600 - Technology E Compact Discs 700 - Art E DVD Videos/Videocassettes 800 - Literature E Foreign Language 900 - Geography & History E New Additions Audiocassettes Fiction Audiovisual Materials Foreign Languages Biographies Graphic Novels CD-ROMs Large Print Fiction Call # Author Title J FIC/AVI Avi, 1937- Midnight magic J FIC/BALLIETT Balliett, Blue, 1955- Chasing Vermeer J FIC/BALLIETT Balliett, Blue, 1955- The Wright 3 J FIC/BARROWS Barrows, Annie. Ivy + Bean take care of the babysitter J FIC/BARROWS 3-4 Barrows, Annie. Ivy + Bean and the ghost that had to go J FIC/BARROWS 3-4 Barrows, Annie. Ivy + Bean break the fossil record J FIC/BARROWS 3-4 Barrows, Annie. The magic half J FIC/BASE Base, Graeme. The discovery of dragons J FIC/BASE Base, Graeme. The eleventh hour : a curious mystery J FIC/BAUER Bauer, Sepp. The Christmas rose J FIC/BAUM Baum, L. Frank The marvelous land of Oz : being an account of the further adventures J FIC/BELL 3-4 Bell, Krista. If the shoe fits J FIC/BENTON 3-4 Benton, Jim. Attack of the 50-ft. Cupid J FIC/CAPOTE Capote, Truman, 1924-1984. A Christmas memory J FIC/CHRONICLES The chronicles of Narnia : the lion the witch and the wardrobe J FIC/CLEMENTS Clements, Andrew, 1949- No talking J FIC/CLEMENTS Clements, Andrew, 1949- Room one : a mystery or two J FIC/COLFER Colfer, Eoin. -

Afterschool for the Global Age

Afterschool for the Global Age Asia Society The George Lucas Educational Foundation Afterschool and Community Learning Network The Children’s Aid Society Center for Afterschool and Community Education at Foundations, Inc. Asia Society Asia Society is an international nonprofi t organization dedicated to strengthening relationships and deepening understanding among the peoples of Asia and the United States. The Society seeks to enhance dialogue, encourage creative expression, and generate new ideas across the fi elds of policy, business, education, arts, and culture. Through its Asia and International Studies in the Schools initiative, Asia Society’s education division is promoting teaching and learning about world regions, cultures, and languages by raising awareness and advancing policy, developing practical models of international education in the schools, and strengthening relationships between U.S. and Asian education leaders. Headquartered in New York City, the organization has offi ces in Hong Kong, Houston, Los Angeles, Manila, Melbourne, Mumbai, San Francisco, Shanghai, and Washington, D.C. Copyright © 2007 by the Asia Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For more on international education and ordering -

Sesame Street Combining Education and Entertainment to Bring Early Childhood Education to Children Around the World

SESAME STREET COMBINING EDUCATION AND ENTERTAINMENT TO BRING EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION TO CHILDREN AROUND THE WORLD Christina Kwauk, Daniela Petrova, and Jenny Perlman Robinson SESAME STREET COMBINING EDUCATION AND ENTERTAINMENT TO Sincere gratitude and appreciation to Priyanka Varma, research assistant, who has been instrumental BRING EARLY CHILDHOOD in the production of the Sesame Street case study. EDUCATION TO CHILDREN We are also thankful to a wide-range of colleagues who generously shared their knowledge and AROUND THE WORLD feedback on the Sesame Street case study, including: Sashwati Banerjee, Jorge Baxter, Ellen Buchwalter, Charlotte Cole, Nada Elattar, June Lee, Shari Rosenfeld, Stephen Sobhani, Anita Stewart, and Rosemarie Truglio. Lastly, we would like to extend a special thank you to the following: our copy-editor, Alfred Imhoff, our designer, blossoming.it, and our colleagues, Kathryn Norris and Jennifer Tyre. The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Support for this publication and research effort was generously provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and The MasterCard Foundation. The authors also wish to acknowledge the broader programmatic support of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the LEGO Foundation, and the Government of Norway. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. -

Sanibona Bangane! South Africa

2003 ANNUAL REPORT sanibona bangane! south africa Takalani Sesame Meet Kami, the vibrant HIV-positive Muppet from the South African coproduction of Sesame Street. Takalani Sesame on television, radio and through community outreach promotes school readiness for all South African children, helping them develop basic literacy and numeracy skills and learn important life lessons. bangladesh 2005 Sesame Street in Bangladesh This widely anticipated adaptation of Sesame Street will provide access to educational opportunity for all Bangladeshi children and build the capacity to develop and sustain quality educational programming for generations to come. china 1998 Zhima Jie Meet Hu Hu Zhu, the ageless, opera-loving pig who, along with the rest of the cast of the Chinese coproduction of Sesame Street, educates and delights the world’s largest population of preschoolers. japan 2004 Sesame Street in Japan Japanese children and families have long benefited from the American version of Sesame Street, but starting next year, an entirely original coproduction designed and produced in Japan will address the specific needs of Japanese children within the context of that country’s unique culture. palestine 2003 Hikayat Simsim (Sesame Stories) Meet Haneen, the generous and bubbly Muppet who, like her counterparts in Israel and Jordan, is helping Palestinian children learn about themselves and others as a bridge to cross-cultural respect and understanding in the Middle East. egypt 2000 Alam Simsim Meet Khokha, a four-year-old female Muppet with a passion for learning. Khokha and her friends on this uniquely Egyptian adaptation of Sesame Street for television and through educational outreach are helping prepare children for school, with an emphasis on educating girls in a nation with low literacy rates among women. -

Children's Television in Asia : an Overview

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Children's television in Asia : an overview Valbuena, Victor T 1991 Valbuena, V. T. (1991). Children's television in Asia : an overview. In AMIC ICC Seminar on Children and Television : Cipanas, September 11‑13, 1991. Singapore: Asian Mass Communiction Research & Information Centre. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/93067 Downloaded on 23 Sep 2021 22:26:31 SGT ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library Children's Television In Asia : An Overview By Victor Valbuena CHILDREN'ATTENTION: ThSe S inTELEVISIONgapore Copyright Act apIpNlie s tASIAo the use: o f thiAs dNo cumOVERVIEent. NanyangW T echnological University Library Victor T. Valbuena, Ph.D. Senior Programme Specialist Asian Mass Communication Research and Information Centre Presented at the ICC - AMIC - ICWF Seminar on Children and Television Cipanas, West Java, Indonesia 11-13 September, 1991 CHILDREN'S TELEVISION IN ASIA: AN OVERVIEW Victor T. Valbuena The objective of this paper is to present an overview of children's AtelevisioTTENTION: The Snin gaiponre CAsiopyrigaht Aanct apdpl iessom to thee u seo off t histh doceu meproblemnt. Nanyang Tsec hnanologdic al issueUniversity sLib rary that beset it . By "children's television" is meant the range of programme materials made available specifically for children — from pure entertainment like televised popular games and musical shows to cartoon animation, comedies, news, cultural perform ances, documentaries, specially made children's dramas, science programmes, and educational enrichment programmes — and trans mitted during time slots designated for children. -

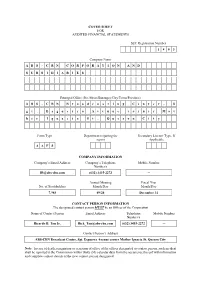

COVER SHEET for AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number 1 8 0 3 Company Name A

COVER SHEET FOR AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number 1 8 0 3 Company Name A B S - C B N C O R P O R A T I O N A N D S U B S I D I A R I E S Principal Office (No./Street/Barangay/City/Town/Province) A B S - C B N B r o a d c a s t i n g C e n t e r , S g t . E s g u e r r a A v e n u e c o r n e r M o t h e r I g n a c i a S t . Q u e z o n C i t y Form Type Department requiring the Secondary License Type, If report Applicable A A F S COMPANY INFORMATION Company’s Email Address Company’s Telephone Mobile Number Number/s [email protected] (632) 3415-2272 ─ Annual Meeting Fiscal Year No. of Stockholders Month/Day Month/Day 7,985 09/24 December 31 CONTACT PERSON INFORMATION The designated contact person MUST be an Officer of the Corporation Name of Contact Person Email Address Telephone Mobile Number Number/s Ricardo B. Tan Jr. [email protected] (632) 3415-2272 ─ Contact Person’s Address ABS-CBN Broadcast Center, Sgt. Esguerra Avenue corner Mother Ignacia St. Quezon City Note: In case of death, resignation or cessation of office of the officer designated as contact person, such incident shall be reported to the Commission within thirty (30) calendar days from the occurrence thereof with information and complete contact details of the new contact person designated. -

October 22, 2020

Natural gas England’s tour will be fastest of South growing Africa going fuel in energy ahead amid mix: GECF CSA crisis Business | 01 Sport | 10 THURSDAY 22 OCTOBER 2020 5 RABIA I - 1442 VOLUME 25 NUMBER 8418 www.thepeninsula.qa 2 RIYALS Watch Disney+ Streaming App Originals as a gift Terms & Conditions Apply Ministry approves Amir visits S’hail 2020 exhibition at Katara rotating attendance QNA — DOHA Amir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani paid a visit to Katara Interna- system for students tional Hunting and Falcons Exhibition (S’hail 2020), The new system shall be schedule, with compulsory which is held at the attendance starting from Wisdom Square of the applied after the end of November 1 for public and Cultural Village Foun- the midterm exams of private schools according to dation - Katara, yesterday their academic calendar after evening. the first semester, as of the end of the mid-term The Amir viewed the November 1, 2020. exams of the first semester, exhibited falcons, hunting which will start from October and sniping supplies and 25 and no later than the various types of The average attendance November 1, provided that the weapons, equipment and rate in all government, blended education system will products used in hunting, be applied according to the in addition to artboards for private schools and kin- weekly rotating attendance sniping trips. dergartens to be raised schedules. The Amir was briefed by All government and private the officials in charge of to 42% of the capacity schools are obligated to divide the exhibition, which is of schools. -

The Educational and Cultural Impact of Sisimpur

PROGRAMME RESEARCH 20/2007/E 51 June H. Lee The educational and cultural impact of Sisimpur Bangladesh’s Sesame Street Since 2005, the Bangladeshi Sesa- me Street.1 In Bangladesh, the me Street is broadcast on national groundwork for Sisimpur began in TV, and specially equipped rick- 2003 when a team from Sesame shaws bring the programme into Workshop visited Bangladesh to as- remote villages. Sisimpur has its sess the feasibility of an educational own special Muppet characters, TV programme for preschoolers. and the programme is found to fos- While Bangladesh has made signifi- ter basic literacy and mathematical cant strides in expanding primary skills as well as the notion of educa- school enrolment in the past decade tion being a joyful experience. (Lusk/Hashemi/Haq, 2004), govern- ment provisions for early childhood education programmes have re- “They teach you what ‘a’ is for, what ‘b’ mained limited. At the same time, te- sic literacy and math skills, health, hy- is for. I learn them. When they ask what levision is a popular medium with giene, nutrition, respect, understand- ‘jha’ is for, Tuktuki flies away in a ‘jhor’ growing reach among the population; ing, diversity, family and community (storm) and then comes down on earth it is also an important avenue for relations, and art and culture. Each again.” disseminating information (such as piece of content produced for Sisim- Ratul, Mirka village, Bhaluka, Bangla- pur addresses a specific educational desh (Kibria, 2006) on health; Associates for Communi- ty and Population Research, 2002). objective. atul, a boy from a village in Using television to deliver educational Sisimpur launched in April 2005 on Bhaluka in Bangladesh, is content promised to be a cost-effecti- Bangladesh Television, the country’s Rspeaking about Sisimpur, the ve way to provide informal early only national television channel.2 The Bangladeshi co-production of Sesa- childhood opportunities to children show is set in a village that centres throughout Bangladesh. -

Bringing Hope and Opportunity to Children

Bringing Hope and Opportunity to Children Affected by Conflict and Crisis Around the World Sesame Workshop and partners are leading the largest coordinated early childhood intervention in the history of humanitarian response. The scale of the global refugee crisis is staggering. Today, more than 70 million people are displaced worldwide — and half are children. The most formative years of their lives have been marked by upheaval, chaos, and violence, all with lasting effects on their development and wellbeing. Millions of young children are spending their childhoods without early childhood development (ECD) opportunities that can help them recover from adverse experiences and prepare them to thrive. In the face of this urgent humanitarian crisis, Sesame Workshop and the International Rescue Committee (IRC), with support from the MacArthur Foundation, partnered to create Ahlan Simsim (“Welcome Sesame” in Arabic), a program that delivers early learning and nurturing care to children and caregivers affected by conflict and displacement in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Building on our ambitious efforts in the Syrian response region, Sesame Workshop has teamed up with the LEGO Foundation, BRAC, and the IRC to support hundreds of thousands of children and caregivers affected by both the Syrian crisis in Jordan and Lebanon and the Rohingya refugee crisis in Bangladesh, by ensuring access to play-based learning opportunities that are vital to their development. Together with other stakeholders, we have the potential to transform humanitarian response, benefitting children affected by conflict and crisis around the world. Ahlan Simsim: Delivering vital early learning to children in the Syrian response region The ongoing conflict in Syria has Mass Media Direct Services displaced over 12 million people. -

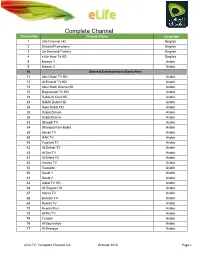

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

Arabic Global 59

ARABIC GLOBAL 59. AL HAYAT CINEMA 120. BAHRAIN SPORT 1 180. AL RASHEED 60. AL NAHAR TV 121. BAHRAIN SPORT 2 181. AL GHADEER 1. AL JAZEERA ARABIC 61. AL HAYAT SPORT 122. BAHRAIN 55 182. AL QETHARA 2. AL JAZEERA ENGLISH 62. AL HAYAT MUSLSALAT 123. BAHRAIN TV 183. OMANN SPORT 3. AL JAZEERA MASR 63. AL HAYAT SERIES 124. ORIENT 184. ALMERGAB 2 4. AL JAZEERA MUBASHER 64. IMAGINE MOVIES 125. AGHAPY 185. TUNISIA TV 5. MBC 1 65. RUSSIA AL YAUM 126. DUBAI TV 186. TUNISIE TELEVISION 6. MBC WANASAH 66. DW TV ARABIC 127. MAEEN 187. MISRATA 7. MBC 4 67. EURO NEWS ARABIC 128. HAMASAT 188. OMAN TV 8. MBC ACTION 68. FUTURE INTERNATIONAL 129. MADANI 189. OMAN TV2 9. MBC MAX 69. FUTURE USA 130. MTV LEBANON 190. SAWSAN TV 10. MBC DRAMA 70. SYRIA SATELLITE 131. NOURSAT AL SHABAB 191. LIBYA AL HURRA 11. MBC MAGHREB 71. CNBC ARABIYAH 132. AL MASRAWIA 192. TOP MOVIES TV 12. MBC 3 72. MBC MASR 133. ABU DHABI DRAMA 2 193. AL HAQEQA 13. MBC PERSIA 73. PANORAMA DRAMA 2 134. AL ANWAR 194. ALL TV 14. MBC 2 74. CRT DRAMA 135. AL MANAR 195. AL LUBNANIA 15. ROTANA CINEMA 75. PANORAMA FILM 136. AL EKHBARIA 196. TAWAZON 16. ROTANA KHALIJIAH 76. PANORAMA DRAMA 137. CORAN TV 197. KIRKUK TV 17. ROTANA MUSIC 77. AL ARABIYAH AL HADATH 138. TELE LIBAN 198. AL FATH 18. ROTANA CLIP 78. AL ALARABIYA 139. AL YAWM PALESTINE 199. FM TV 19. ROTANA MASRIYA 79. FADAK TV 140. BEDAYA 200.