Game of Loans: How China Bought Hambantota

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of Sri Lanka Department of International Trade Promotion Thai Trade Centre, Chennai, India

00 Republic of Sri Lanka Department of International Trade Promotion Thai Trade Centre, Chennai, India General Information Capital City : Colombo Surface Area : 65, 610 km² Districts : 25 Population : 21,036,374 (2015) Official Language : Sinhalese, Tamil Currency : Sri Lankan Rupee President : Maithripala Sirisena (Jan 2015) (1 USD = 180.01 LKR (Feb 2019)) Prime Minister : Ranil Wickremesinghe (Oct 2018) Religion : Buddhism (70%), Hinduism (13%), Others (17%) Ref : www.gov.lk Economic Indicators 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 GDP (USD $ bn) 59.2 59.4 67.6 74.6 80.6 81.00 GDP PPP 169.3 183.2 199.6 217.4 233.6 261.07 GDP per capita (US $) 2,880.0 2,874.0 3,239.0 3,558.0 3,818.0 3,811.00 Real GDP growth 8.2 6.3 7.3 7.4 6.5 4.4 Current account balance (US $ mn) -4,615.0 -3,981.0 -2,606.0 -2,790.0 -1,639.0 -1.72 Current account balance (% GDP) -7.8 -6.7 -3.9 -3.7 -2.0 -2.49 Goods & Services exports (% GDP) 23.1 22.9 22.4 22.3 21.9 10.3 Inflation 6.7 7.5 6.9 3.3 1.7 3.73 Ref : www.data.worldbank.org Connectivity GDP Composition % Natural Resources International Airport : 1 (Bandaranaike) Service 56.78 % - Limestone - Gems Domestic Airports : 1 (Ratmalana) Industry 32.46 % - Graphite - Phosphates Major Sea Ports : 3 (Colombo, Hambantota, Trincomalee) Manufacturing 17.71 % - Mineral Sands - Clay Minor Sea Ports : 3 (Galle, Point Pedro, Kankesanthurai) Agriculture 12.76 % - Hydro Power - Arable Land Ref : www.airport.lk Ref : www.tradingeconomics.com Ref : CIA/The World Factbook Major Exports Major Imports Major Industries Major Cities Textile -

Download.Php?File=MBB 585Bbd2c MBB User Guide 7June11.Docx

District Investment Case Analysis Recommendations, guidlines and action plan Sri Lanka This report was prepared by Shanthi Dalpatadu, Shanaz Saleem and Ravi P. Rannan-Eliya March - 2012 Table of Contents List of Tables ....................................................................................................................................... iv List of Figures ....................................................................................................................................... v Abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................... viii Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 1: Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 13 Chapter 2: Summary of DICA ........................................................................................................... 15 2.1 Summary of process ............................................................................................................... 15 2.1.1 Issues encountered ......................................................................................................... 16 2.1.2 Positives ......................................................................................................................... -

A Cost Analysis of Coastal Shipping of Sri Lanka

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 2000 A cost analysis of coastal shipping of Sri Lanka Nishanthi Perera WMU Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Perera, Nishanthi, "A cost analysis of coastal shipping of Sri Lanka" (2000). World Maritime University Dissertations. 1109. https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/1109 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non-commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmö, Sweden A Cost Analysis of Coastal Shipping of Srilanka By PERERA D. K. NISHANTHI Srilanka A dissertation submitted to the World Maritime University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in SHIPPING MANAGEMENT 2000 © Copyright Perera D. K. Nishanti, 2000 DECLARATION I certify that all the material in this dissertation that is not my own work has been identified, and that no material is included for which a degree has previously been conferred on me. The contents of this dissertation reflect my own personal views, and are not necessarily endorsed by the University. ----------------------------- (Signature) ----------------------------- (Date) Supervised by: Tor Wergeland Associate Professor, Shipping Management World Maritime University Assessor: David J. Mottram Adjunct Professor Former Course Professor, Shipping Management World Maritime University Co-Assessor: Anna – Kari Bill Head, Finance & Administration World Maritime University i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the Ceylon Shipping Corporation for nominating and allowing me to attend this course at the World Maritime University. -

The Case of Sri Lanka

June 2015 PLANNED RELOCATIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF NATURAL DISASTERS : THE CASE OF S RI LANKA AUTHORED BY: Ranmini Vithanagama Alikhan Mohideen Danesh Jayatilaka Rajith Lakshman Centre for Migration Research and Development Planned Relocations in Sri LankaColombo, Sri Lanka Page i Planned Relocations in Sri Lanka Page ii The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings research are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Support for this publication was generously provided by The John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment. 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 www.brookings.edu © 2015 Brookings Institution Front Cover Photograph: Resettlement housing in Kananke Watta, Sri Lanka (Danesh Jayatilaka, March 2015). Planned Relocations in Sri Lanka Page iii THE AUTHORS The Centre for Migration Research and Development is a nonprofit company based in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Its purpose is to build knowledge and understanding of the interaction between migration and development, especially in the context of Sri Lanka. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This case study was carried out at the request of the Brookings-LSE Project on Internal Displacement to be used in preparing for the expert consultation on Planned Relocations, Disasters, and Climate Change to be held in 2015. -

Spatial Variability of Rainfall Trends in Sri Lanka from 1989 to 2019 As an Indication of Climate Change

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Spatial Variability of Rainfall Trends in Sri Lanka from 1989 to 2019 as an Indication of Climate Change Niranga Alahacoon 1,2,* and Mahesh Edirisinghe 1 1 Department of Physics, University of Colombo, Colombo 00300, Sri Lanka; [email protected] 2 International Water Management Institute (IWMI), 127, Sunil Mawatha, Pelawatte, Colombo 10120, Sri Lanka * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Analysis of long-term rainfall trends provides a wealth of information on effective crop planning and water resource management, and a better understanding of climate variability over time. This study reveals the spatial variability of rainfall trends in Sri Lanka from 1989 to 2019 as an indication of climate change. The exclusivity of the study is the use of rainfall data that provide spatial variability instead of the traditional location-based approach. Henceforth, daily rainfall data available at Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation corrected with stations (CHIRPS) data were used for this study. The geographic information system (GIS) is used to perform spatial data analysis on both vector and raster data. Sen’s slope estimator and the Mann–Kendall (M–K) test are used to investigate the trends in annual and seasonal rainfall throughout all districts and climatic zones of Sri Lanka. The most important thing reflected in this study is that there has been a significant increase in annual rainfall from 1989 to 2019 in all climatic zones (wet, dry, intermediate, and Semi-arid) of Sri Lanka. The maximum increase is recorded in the wet zone and the minimum increase is in the semi-arid zone. -

Port of Hambantota

2016 PORT OF HAMBANTOTA SRI LANKA PORTS AUTHORITY Port of Hambantota Page 1 1. INTRODUCTION Located in the Indian Ocean, bordering on the equator, the island of Sri Lanka boasts of a rich history of civilization, rulers, religion, traditions and marvels of engineering. A 30,000 year history beginning with the “Balangoda Manawaya” to the present Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, the country has had its fair share of influences but has always remained true to its identity of being the “Pearl of the Indian Ocean”. Due to the unique geographical nature as well as its global position, the island of Sri Lanka became a prime target for European Conquerors during the Colonial Era. From the beginning of 16th century up to the mid-20th century, initially the coastal areas and later the whole island was under the governance of European Empires. Since, the independence in 1948, Sri Lanka has been through its thick and thin of geo-political troubles and has blossomed into a unique destination for multinational trade, tourists, entrepreneurs, etc. Trade via sea routes has always been the prime source, which generated international trade to Sri Lanka. Hence, the establishment of Sri Lanka Ports Authority in 1979 under the act “The Sri Lanka Ports Authority Act No. 51 of 1979” was a critical juncture in the economic development timeline of Sri Lanka. It enabled a single entity to develop maintain, operate and oversee all activities in relation to the Port Sector of Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka Ports Authority currently owns a total of seven Ports located all around the island. -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF JULY 2017 MEMBERSHI P CHANGES CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 3846 025586 COLOMBO HOST REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 32 0 0 0 0 0 32 3846 025591 DEHIWALA MT LAVINIA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 39 0 0 0 0 0 39 3846 025592 GALLE REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 46 0 0 0 0 0 46 3846 025604 MORATUWA RATMALANA LC REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 35 0 0 0 -1 -1 34 3846 025611 PANADURA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 32 0 0 0 0 0 32 3846 025614 WELLAWATTE REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 32 0 0 0 -4 -4 28 3846 030299 KOLLUPITIYA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 17 0 0 0 0 0 17 3846 032756 MORATUWA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 50 0 0 0 -2 -2 48 3846 036615 TANGALLE REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 30 0 0 0 0 0 30 3846 038353 KOTELAWALAPURA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 06-2017 28 0 0 0 0 0 28 3846 041398 HIKKADUWA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 06-2017 20 0 0 0 0 0 20 3846 041399 WADDUWA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 38 0 0 0 0 0 38 3846 043171 BALAPITIYA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 06-2017 14 0 0 0 0 0 14 3846 043660 MORATUWA MORATUMULLA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 20 0 0 0 0 0 20 3846 045938 KALUTARA CENTRAL REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 06-2017 21 0 0 0 0 0 21 3846 046170 GALKISSA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 43 1 0 0 0 1 44 3846 048945 DEHIWALA METRO REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A1 4 07-2017 20 0 0 0 0 0 20 3846 051562 ALUTHGAMA -

China - Sri Lanka Strategic Hambantota Port Deal

http://www.maritimeindia.org/ China - Sri Lanka Strategic Hambantota Port Deal Author: Anjelina Patrick* Date: 13 April 2017 Introduction Sri Lanka is conscious of its geostrategic position, and the advantage its ports hold in the Indian Ocean Region. One such port is the Hambantota Port, situated along one of the world's busiest east-west shipping routes, which passes 10 nautical miles from Hambantota. The island country holds the potential to become an advanced commercial hub so as to accelerate the country’s economy and trade, with the help of infrastructural investment from foreign entities like China. China has already invested USD 2 billion on the Hambantota Port Development Project. These investments were made without any feasible study or consideration of other repayment options. The port’s existing economic non-viability, massive maintenance expenses, and huge interest payments have led to a serious ‘debt trap’ for the island country. In December 2006, the initial agreement between the two parties was signed; wherein the Sri Lankan government was expected to sell 80 per cent stake in the Hambantota port for a 99-year lease, for USD1.12 billion. This issue brief aims to trace the development of the Hambantota Port Development Project vis-a-vis the degrading economy of Sri Lanka. It further examines the implications of the proposed agreement on the security, politics, and society of Sri Lanka. It also attempts to analyze China’s intentions behind the huge non-viable investment. Background The Hambantota port is an initiative of the Lankan government to further develop the strategic port and proposed industrial zone of 1,235 acres. -

Debunking the Myth of 'Debt-Trap Diplomacy'

Research Paper Lee Jones and Shahar Hameiri Asia-Pacific Programme | August 2020 Debunking the Myth of ‘Debt-trap Diplomacy’ How Recipient Countries Shape China’s Belt and Road Initiative Contents Summary 2 1 Introduction 3 2 The Economic Drivers of the BRI 5 3 Governing the Belt and Road 8 4 Sri Lanka and the BRI 13 5 Malaysia and the BRI 20 6 Conclusion and Policy Recommendations 28 About the Authors 31 Acknowledgments 32 References 33 1 | Chatham House Debunking the Myth of ‘Debt-trap Diplomacy’: How Recipient Countries Shape China’s Belt and Road Initiative Summary • The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is seen by some as a geopolitical strategy to ensnare countries in unsustainable debt and allow China undue influence. However, the available evidence challenges this position: economic factors are the primary driver of current BRI projects; China’s development financing system is too fragmented and poorly coordinated to pursue detailed strategic objectives; and developing-country governments and their associated political and economic interests determine the nature of BRI projects on their territory. • The BRI is being built piecemeal, through diverse bilateral interactions. Political-economy dynamics and governance problems on both sides have led to poorly conceived and managed projects. These have resulted in substantial negative economic, political, social and environmental consequences that are forcing China to adjust its BRI approach. • In Sri Lanka and Malaysia, the two most widely cited ‘victims’ of China’s ‘debt-trap diplomacy’, the most controversial BRI projects were initiated by the recipient governments, which pursued their own domestic agendas. Their debt problems arose mainly from the misconduct of local elites and Western-dominated financial markets. -

Impacts of Hurricane Katrina & Boxing Indian Ocean Tsunami on Ports

Impacts of Hurricane Katrina & Boxing Indian Ocean Tsunami On Ports & Harbors Facilities Engineering Seminar American Associate of Port Authorities January 11-13, 2006 By John Headland We learn from history, that we learn nothing from history.” George Bernard Shaw Author, Playwright TRINCOMALEE COLOMBO GALLE DayDay 11 #13#13 TypicalTypical SriSri LankanLankan SceneScene NearNear PanaduraPanadura TsunamiTsunami InundationInundation == 3.33.3 mm East Sri Lanka (AP Photo): Raging water at beach front properties. DayDay 44 #19#19 HambantotaHambantota SriSri LankaLanka Runup=Runup= 11m11m Thailand Sumatra Runup by Philip Liu Tsunami Impacts On Ports & Harbors Port of Colombo •General cargo terminal and 2 container terminals •12-15 m draft (Jaya) and 9-11 m draft (SAGT) •2 million T.E.U in 2004 •Reinforced concrete deck on piles •200 Ha water area, 130 Ha land area Tsunami Height = 2.6 m DayDay 22 ## 55 PortPort ofof ColomboColombo SriSri LankaLanka NoNo DiscernableDiscernable DamageDamage DayDay 22 ## 3737 PortPort ofof ColomboColombo SriSri LankaLanka AA ShipShip LostLost ControlControl InIn ThisThis EntranceEntrance DuringDuring thethe TsunamiTsunami Tsunami Height= 5.3 m DayDay 11 #100#100 SriSri LankaLanka PortPort ofof GalleGalle 2m2m SedimentationSedimentation DuringDuring TsunamiTsunami DayDay 11 #108#108 SriSri LankaLanka PortPort ofof GalleGalle WarehouseWarehouse DamageDamage DayDay 11 ## 115115 SriSri LankaLanka PortPort ofof GalleGalle DredgeDredge GroundedGrounded OnOn WharfWharf TsunamiTsunami Height=Height= 5.35.3 mm Areas Visited -

ADCHA/OFDA Yemen Complex Program

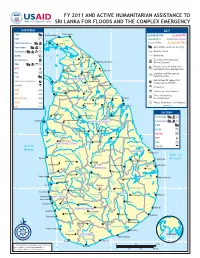

FY 2011 AND ACTIVE HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO SRI LANKA FOR FLOODS AND THE COMPLEX EMERGENCY 10° NORTHERN 80° 81° KEY82° 10° !0 FAO A Kankesanturai Point Pedro USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP IOM USAID/OTI USAID/Sri Lanka a Kayts JaffnaJaffna Practical Action AC Jaffna State/PRM State/PM/WRA Sarvodaya AC A Agriculture and Food Security J H Sewalanka ACIJ Cash-for-Work OCHA } Demining B Kilinochchi World Vision C KilinochchiKilinochchi Economic Recovery and !0 Puthukkudiyiruppu C Market Systems ZOARamesvaram CIJ A Nanthi Humanitarian Coordination WFP MullaittivuMullaittivu Kadal B and Information Management Mullaittivu Vellankulam Mankulam DAI a Logistics and Emergency Talaimannar a FAO Nedunkeni Relief Supplies A NORTHERNNORTHERN Antares9° Foundation Puliyankulam Mental Health Support for 9° Mannar Humanitarian Workers UNHCR VavuniyaVavuniya Pulmoddai G MannarMannar G Protection DDG } Paraiyanalankulam Yan Vavuniya Oya I Shelter and Settlements FSD } Silavatturai TrincomaleeTrincomalee Title II Emergency HALO Trust } Kebitigollewa Pan Kulam Nilaveli Food Assistance MAG Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene } Medawachchiya !0 J Trincomalee MLI } Horowupotana 09/30/11 AnuradhapuraAnuradhapura EASTERN Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantale Aruvi Sarvodaya Yan Oya ACJ Aru Kalpitiya Maragahawewa Sewalanka Kala NORTH-CENTRALNORTH-CENTRAL ACJ Oya PolonnaruwaPolonnaruwa FAO A SC/US Kekirawa Minneriya a Puttalam ACTED H 8° PuttalamPuttalam 8° Polonnaruwa WFP Anamaduwa Dambulla DAI NORTH-WESTERNNORTH-WESTERN !0 a Gulf of BatticaloaBatticaloa UNHCR Deduru G Oya Mannar Oya -

Reference Map

SRI LANKA - Reference Map Tellippalai Point Pedro Chankanai Karaveddy J A F F N A Bay of Uduvil Bengal Kayts Kopai North Palk Strait Velanai Nallur Chavakachcheri Jaffna Maruthankerny Pallai Marelithurai Kandavalai Kilinochchi K I L I N O C H C H I Puthukudiyiruppu Palk Bay Mullaittivu MMUULLL AATTTTIIVVUU Tunukkai Oddusuddan INDIA Kokkilai Mannar N O R T H E R N Lagoon Adampam Padavi Siripura Gulf of Madhu Padawiya Mannar M A N N A R Kuchchaveli VAV U N I YA Yan Oya Silavatturai Vavuniya Gomarankadawala Kebitigollewa Elevation (meters) 5,000 and above Morawewa Trincomalee 4,000 - 5,000 Mahawilachchiya Horowupotana Tampalakamam Koddiyar Bay A N U R A D H A P U R A Periyakinniya 3,000 - 4,000 Mutur N O R T H C E N T R A L 2,500 - 3,000 Mihintale Seruvila 2,000 - 2,500 Anuradhapura Galenbindunuwewa T R I N C O M A L E E Nochchiyagama 1,500 - 2,000 Kala Oya Aruvi Aru Kalpitiya Verukal Nachchaduwa 1,000 - 1,500 Vannatavillu Puttalam 800 - 1,000 Lagoon PUTTALAM 600 - 800 Karuwalagaswewa Palugaswewa P O L O N N A R U WA Kekirawa 400 - 600 Puttalam Lankapura Nawagattegama Kudagalnewa 200 - 400 Welikanda 0 - 200 Anamaduwa Polonnaruwa Below sea level Mahakumbukkadawala Dambulla Mundal Mundel Lake P U T TA L A M Elahera B AT T I C A L O A Batticaloa Pallama Deduru Oya Madura Oya Arachchikattuwa M ATA L E Madura Oya Chilaw N O R T H W E S T E R N Reservoir E A S T E R N Madampe Matale Kurunegala Maha Oya Pahala Mahawewa Kalmunai Nattandiya C E N T R A L Sammanthurai Saintamaruthu Wennappuwa Oya Uhana Nintavur aha Dankotuwa M Kandy Ganga Mahaweli