Americanensemble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Manatee PIANO MUSIC of the Manatee BERNARD

The Manatee PIANO MUSIC OF The Manatee BERNARD HOFFER TROY1765 PIANO MUSIC OF Seven Preludes for Piano (1975) 15 The Manatee [2:36] 16 Stridin’ Thru The Olde Towne 1 Prelude [2:40] 2 Cello [2:47] During Prohibition In Search Of A Drink [2:42] 3 All Over The Piano [1:21] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 4 Ships Passing [4:12] (2014) BERNARD HOFFER 5 Prelude [1:24] Events & Excursions for Two Pianos 6 Calypso [3:52] 17 Big Bang Theory [3:15] 7 Franz Liszt Plays Ragtime [3:28] 18 Running [3:19] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 19 Wexford Noon [2:29] 20 Reverberations [3:12] Nine New Preludes for Piano (2016) 21 On The I-93 [2:23] Randall Hodgkinson & Leslie Amper, pianos 8 Undulating Phantoms [1:08] BERNARD HOFFER 9 A Walk In The Park [2:39] 10 Speed Chess [2:17] 22 Naked (2010) [5:05] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 11 Valse Sentimental [3:30] 12 Rabbits [1:06] Total Time = 60:03 13 Spirals [1:40] 14 Canon Inverso [1:44] PIANO MUSIC OF TROY1765 WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1765 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2019 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. The Manatee PIANO MUSIC OF The Manatee BERNARD HOFFER WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1765 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. -

Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UPDATED January 13, 2015 January 7, 2015 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] ALAN GILBERT AND THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC Alan Gilbert To Conduct SILK ROAD ENSEMBLE with YO-YO MA Alongside the New York Philharmonic in Concerts Celebrating the Silk Road Ensemble’s 15TH ANNIVERSARY Program To Include The Silk Road Suite and Works by DMITRI YANOV-YANOVSKY, R. STRAUSS, AND OSVALDO GOLIJOV February 19–21, 2015 FREE INSIGHTS AT THE ATRIUM EVENT “Traversing Time and Trade: Fifteen Years of the Silkroad” February 18, 2015 The Silk Road Ensemble with Yo-Yo Ma will perform alongside the New York Philharmonic, led by Alan Gilbert, for a celebration of the innovative world-music ensemble’s 15th anniversary, Thursday, February 19, 2015, at 7:30 p.m.; Friday, February 20 at 8:00 p.m.; and Saturday, February 21 at 8:00 p.m. Titled Sacred and Transcendent, the program will feature the Philharmonic and the Silk Road Ensemble performing both separately and together. The concert will feature Fanfare for Gaita, Suona, and Brass; The Silk Road Suite, a compilation of works commissioned and premiered by the Ensemble; Dmitri Yanov-Yanovsky’s Sacred Signs Suite; R. Strauss’s Death and Transfiguration; and Osvaldo Golijov’s Rose of the Winds. The program marks the Silk Road Ensemble’s Philharmonic debut. “The Silk Road Ensemble demonstrates different approaches of exploring world traditions in a way that — through collaboration, flexible thinking, and disciplined imagination — allows each to flourish and evolve within its own frame,” Yo-Yo Ma said. -

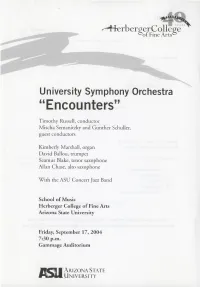

University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters"

FierbergerCollegeYEARS of Fine Arts University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters" Timothy Russell, conductor Mischa Semanitzky and Gunther Schuller, guest conductors Kimberly Marshall, organ David Ballou, trumpet Seamus Blake, tenor saxophone Allan Chase, alto saxophone With the ASU Concert Jazz Band School of Music Herberger College of Fine Arts Arizona State University Friday, September 17, 2004 7:30 p.m. Gammage Auditorium ARIZONA STATE M UNIVERSITY Program Overture to Nabucco Giuseppe Verdi (1813 — 1901) Timothy Russell, conductor Symphony No. 3 (Symphony — Poem) Aram ifyich Khachaturian (1903 — 1978) Allegro moderato, maestoso Allegro Andante sostenuto Maestoso — Tempo I (played without pause) Kimberly Marshall, organ Mischa Semanitzky, conductor Intermission Remarks by Dean J. Robert Wills Remarks by Gunther Schuller Encounters (2003) Gunther Schuller (b.1925) I. Tempo moderato II. Quasi Presto III. Adagio IV. Misterioso (played without pause) Gunther Schuller, conductor *Out of respect for the performers and those audience members around you, please turn all beepers, cell phones and watches to their silent mode. Thank you. Program Notes Symphony No. 3 – Aram Il'yich Khachaturian In November 1953, Aram Khachaturian acted on the encouraging signs of a cultural thaw following the death of Stalin six months earlier and wrote an article for the magazine Sovetskaya Muzika pleading for greater creative freedom. The way forward, he wrote, would have to be without the bureaucratic interference that had marred the creative efforts of previous years. How often in the past, he continues, 'have we listened to "monumental" works...that amounted to nothing but empty prattle by the composer, bolstered up by a contemporary theme announced in descriptive titles.' He was surely thinking of those countless odes to Stalin, Lenin and the Revolution, many of them subdivided into vividly worded sections; and in that respect Khachaturian had been no less guilty than most of his contemporaries. -

Windward Passenger

MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE BURRELL WINDWARD PASSENGER PHEEROAN NICKI DOM HASAAN akLAFF PARROTT SALVADOR IBN ALI Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : PHEEROAN aklaff 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : nicki parrott 7 by jim motavalli General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : dave burrell 8 by john sharpe Advertising: [email protected] Encore : dom salvador by laurel gross Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : HASAAN IBN ALI 10 by eric wendell [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : space time by ken dryden US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIVAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD ReviewS 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Miscellany 43 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Event Calendar 44 Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Kevin Canfield, Marco Cangiano, Pierre Crépon George Grella, Laurel Gross, Jim Motavalli, Greg Packham, Eric Wendell Contributing Photographers In jazz parlance, the “rhythm section” is shorthand for piano, bass and drums. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

-•-'" 8ft :: -'•• t' - ms>* '-. "*' - h.- ••• ; ''' ' : '..- - *'.-.•..'•••• lS*-sJ BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER see ERICH LEINSDORF, Director Contemporary JMusic Presented under the Auspices of the Fromm zMusic Foundation at TANGLEWOOD 1963 SEMINAR in Contemporary Music Seven sessions will be given on successive Friday afternoons (at 3:15) in the Chamber Music Hall. Four of these will precede the four Fromm Fellows' Concerts, and will consist of a re- hearsal and lecture by the Host of the following Monday Fromm Concert. July 12 AARON COPLAND July 19 GUNTHER SCHULLER July 26 I Twentieth Century Piano Music PAUL JACOBS August 2 YANNIS XENAKIS j August 9 Twentieth Century Choral Music ALFRED NASH PATTERSON & LORNA COOKE de VARON August 16 I LUKAS FOSS August 23 Round Table Discussion of Contemporary Music Yannis Xenakis, Gunther Schuller and lukas foss Composers 9 Forums There will be four Composers' Forums in the Chamber Music Hall: Wednesday, July 24 at 4:00 ] Thursday, August 1 at 8:00 Wednesday, August 7 at 4:00 Thursday, August 15 at 8:00 FROMM FELLOWS' CONCERTS Theatre-Concert Hall Four Monday Evenings at 8:00 'Programs JULY 15 AUGUST 5 AARON COPLAND, Host YANNIS XENAKIS, Host Varese Octandre (1924) Boulez ...Improvisations sur Mallarme, Copland Sextet (1937) No. 2 Chavez Soli (1933) Philippot ...Variations Schoenberg String Quartet No. 2, Op. 10 Mdcbe .. ..Canzone II (1908) Brown, E ...Pentathis Stravinsky Ragtime for Eleven Instruments Marie, E... Polygraphie-Polyphonique (1918) J. Ballif,C ...Double Trio, 35, Nos. 2 and 3 Milhaud... L'Enlevement d'Europe — Op. Xenakis Achorripsis Opera minute (1927) JULY 22 AUGUST 19 GUNTHER SCHULLER, Host LUKAS FOSS, Host Ives Chromatimelodtune Paz .Dedalus, 1950 Schoenberg Herzgewacb.se Goehr... -

Les Paul the Search for the New Sound Biography Written By

Les Paul The Search for the New Sound Biography written by: Becky Marburger Educational Producer Wisconsin Media Lab Table of Contents Introduction . 2 Early Life . 3 Instruments and Experiments . 4 Hitting the Road . 6 Growing Career . 8 Conclusion . 10 Glossary . 11 Introduction Les Paul’s mother often told him, “It’s your life . It’s up to you ”. She wanted her son to go for his dreams . Les was a musician and an inventor . He dreamed of creating a new sound . Musicians today still use Les’s inventions and music . Courtesy of the Les Paul Foundation . Lester (Les) William Polsfuss 2 Early Life Lester William Polsfuss (Les) was born on June 9, 1915, in Waukesha, Wisconsin . His father worked at a car dealership . His mother took care of the family’s home . His parents separated when he was young . Les’s mother knew he liked music . When he did things like take apart her radio, she did not punish him . Les liked watching his mother work her player piano . He sometimes punched holes in paper rolls and put them in the piano to see if they would make new sounds . Moving to Waukesha In the early 1900s, there were many German immigrants living in Waukesha, including Les’s grandfathers . His paternal grandfather immigrated to the United States from Prussia to escape wars and poverty . His maternal grandfather moved from Germany to the United States in search of a new job . Life was not always easy for immigrants . When Les’s mother was young, she had to drop out of school and get a job to help Prussia was a German kingdom that was earn money for her family . -

MUNI 20101013 Piano 02 – Scott Joplin, King of Ragtime – Piano Rolls

MUNI 20101013 Piano 02 – Scott Joplin, King of Ragtime – piano rolls An der schönen, blauen Donau – Walzer, op. 314 (Johann Strauss, Jr., 1825-1899) Wiener Philharmoniker, Carlos Kleiber. Musikverein Wien, 1. 1. 1989 1 intro A 1:38 2 A 32 D 0:40 3 B 16 A 0:15 4 B 16 0:15 5 C 16 D 0:15 6 C 16 0:15 7 D 16 Bb 0:17 8 C 16 D 0:15 9 E 16 G 0:15 10 E 16 0:15 11 F 16 0:14 12 F 16 0:13 13 modul. 4 ►F 0:05 14 G 16 0:20 15 G 16 0:18 16 H 16 0:14 17 H 16 0:15 18 10+1 ►A 0:10 19 I 16 0:17 20 I 16 0:16 21 J 16 0:13 22 J 16 0:13 23 16+2 ►D 0:16 24 C 16 0:15 25 16 ►F 0:15 26 G 14 0:17 27 11 ►D 0:10 28 A 0:39 29 A1 16 0:16 30 A2 0:12 31 stretta 0:10 The Entertainer (Scott Joplin) (copyright John Stark & Son, Sedalia, 29. 12. 1902) piano roll Classics of Ragtime 0108 32 intro 4 C 0:06 33 A 16 0:23 34 A 16 0:23 35 B 16 0:23 36 B 16 0:23 37 A 16 0:23 38 C 16 F 0:22 39 C 16 0:22 40 modul. 4 ►C 0:05 41 D 16 0:22 42 D 16 0:23 43 The Crush Collision March (Scott Joplin, 1867/68-1917) 4:09 (J. -

Rehearing Beethoven Festival Program, Complete, November-December 2020

CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 2020-2021 Friends of Music The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL November 20 - December 17, 2020 The Library of Congress Virtual Events We are grateful to the thoughtful FRIENDS OF MUSIC donors who have made the (Re)Hearing Beethoven festival possible. Our warm thanks go to Allan Reiter and to two anonymous benefactors for their generous gifts supporting this project. The DA CAPO FUND, established by an anonymous donor in 1978, supports concerts, lectures, publications, seminars and other activities which enrich scholarly research in music using items from the collections of the Music Division. The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1992 by William Remsen Strickland, noted American conductor, for the promotion and advancement of American music through lectures, publications, commissions, concerts of chamber music, radio broadcasts, and recordings, Mr. Strickland taught at the Juilliard School of Music and served as music director of the Oratorio Society of New York, which he conducted at the inaugural concert to raise funds for saving Carnegie Hall. A friend of Mr. Strickland and a piano teacher, Ms. Hull studied at the Peabody Conservatory and was best known for her duets with Mary Howe. Interviews, Curator Talks, Lectures and More Resources Dig deeper into Beethoven's music by exploring our series of interviews, lectures, curator talks, finding guides and extra resources by visiting https://loc.gov/concerts/beethoven.html How to Watch Concerts from the Library of Congress Virtual Events 1) See each individual event page at loc.gov/concerts 2) Watch on the Library's YouTube channel: youtube.com/loc Some videos will only be accessible for a limited period of time. -

Industry Bio.Pages

Joe Deninzon ! World’s Premiere Alternative! Violinist! Contact: Anne Leighton: 718-881-8183, [email protected] www.joedeninzon.com ! Hailed as “The Jimi Hendrix of the Violin,” Joe Deninzon is quickly rising as a performer, composer, and favorite of the youth set. He solos his works with professional and school orchestras, plus performs in the rising hip-hop/Latin/Classical Quartet Sweet Plantain. Joe leads Stratospheerius, a progressive rock band that has co-created the SonicVoyageFest in the Northeast U.S. Deninzon transcends many genres, having worked with Bruce Springsteen, Phoebe Snow, Everclear, Smokey Robinson, Aretha Franklin, Robert Bonfiglio, and Les Paul among many others. A 14-time BMI Jazz Composer’s grant recipient and winner of the John Lennon Songwriting Contest, he recently wrote a solo piece commissioned for violinist Rachel Barton Pine and is set to premier his Electric Violin Concerto with the Muncie Symphony Orchestra on September 19, 2015. Joe wrote a book on electric violin techniques for Mel Bay Publications, entitled “Plugging In.” BLOGCRITICS compares Deninzon to "Jeff Beck (as a) "fiddlemaster with a streak of humor." Binghamton's PRESS & SUN BULLETIN calls the group “innovative." THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER praises Stratospheerius for its "funky electric violins, driving guitar rhythms, and fevered drumming layered in an explosive !fashion." ! ! ! ! New Stratospheerius video for "One Foot in the Next World" !http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u7ad4iCYIOI&feature=youtu.be !"Plugging In" by Joe Deninzon available now from Mel Bay Publications All music and merch available at http://stratospheerius.com/store/ !and http://www.joedeninzon.com/discography/ Click here for upcoming performances www.joedeninzon.com www.stratospheerius.com www.facebook.com/stratospheerius !www.reverbnation.com/stratospheerius Contact: Anne Leighton: 718-881-8183 [email protected] . -

Program Book Final 1-16-15.Pdf

4 5 7 BUFFALO PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA TABLE OF CONTENTS | JANUARY 24 – FEBRUARY 15, 2015 BPO Board of Trustees/BPO Foundation Board of Directors 11 BPO Musician Roster 15 Happy Birthday Mozart! 17 M&T Bank Classics Series January 24 & 25 Alan Parsons Live Project 25 BPO Rocks January 30 Ben Vereen 27 BPO Pops January 31 Russian Diversion 29 M&T Bank Classics Series February 7 & 8 Steve Lippia and Sinatra 35 BPO Pops February 13 & 14 A Very Beary Valentine 39 BPO Kids February 15 Corporate Sponsorships 41 Spotlight on Sponsor 42 Meet a Musician 44 Annual Fund 47 Patron Information 57 CONTACT VoIP phone service powered by BPO Administrative Offices (716) 885-0331 Development Office (716) 885-0331 Ext. 420 BPO Administrative Fax Line (716) 885-9372 Subscription Sales Office (716) 885-9371 Box Office (716) 885-5000 Group Sales Office (716) 885-5001 Box Office Fax Line (716) 885-5064 Kleinhans Music Hall (716) 883-3560 Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra | 499 Franklin Street, Buffalo, NY 14202 www.bpo.org | [email protected] Kleinhan's Music Hall | 3 Symphony Circle, Buffalo, NY 14201 www.kleinhansbuffalo.org 9 MESSAGE FROM BOARD CHAIR Dear Patrons, Last month witnessed an especially proud moment for the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra: the release of its “Built For Buffalo” CD. For several years, we’ve presented pieces commissioned by the best modern composers for our talented musicians, continuing the BPO’s tradition of contributing to classical music’s future. In 1946, the BPO made the premiere recording of the Shostakovich Leningrad Symphony. Music director Lukas Foss was also a renowned composer who regularly programmed world premieres of the works of himself and his contemporaries. -

Aspects of Jazz and Classical Music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2002 Aspects of jazz and classical music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations on a Theme of Paganini Heather Koren Pinson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Pinson, Heather Koren, "Aspects of jazz and classical music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations on a Theme of Paganini" (2002). LSU Master's Theses. 2589. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2589 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASPECTS OF JAZZ AND CLASSICAL MUSIC IN DAVID N. BAKER’S ETHNIC VARIATIONS ON A THEME OF PAGANINI A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in The School of Music by Heather Koren Pinson B.A., Samford University, 1998 August 2002 Table of Contents ABSTRACT . .. iii INTRODUCTION . 1 CHAPTER 1. THE CONFLUENCE OF JAZZ AND CLASSICAL MUSIC 2 CHAPTER 2. ASPECTS OF MODELING . 15 CHAPTER 3. JAZZ INFLUENCES . 25 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 48 APPENDIX 1. CHORD SYMBOLS USED IN JAZZ ANALYSIS . 53 APPENDIX 2 . PERMISSION TO USE COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL . 54 VITA . 55 ii Abstract David Baker’s Ethnic Variations on a Theme of Paganini (1976) for violin and piano bring together stylistic elements of jazz and classical music, a synthesis for which Gunther Schuller in 1957 coined the term “third stream.” In regard to classical aspects, Baker’s work is modeled on Nicolò Paganini’s Twenty-fourth Caprice for Solo Violin, itself a theme and variations. -

The Media and Reserve Library, Located on the Lower Level West Wing, Has Over 9,000 Videotapes, Dvds and Audiobooks Covering a Multitude of Subjects

Libraries MUSIC The Media and Reserve Library, located on the lower level west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 24 Etudes by Chopin DVD-4790 Anna Netrebko: The Woman, The Voice DVD-4748 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 Anne Sophie Mutter: The Mozart Piano Trios DVD-6864 25th Anniversary Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Concerts DVD-5528 Anne Sophie Mutter: The Mozart Violin Concertos DVD-6865 3 Penny Opera DVD-3329 Anne Sophie Mutter: The Mozart Violin Sonatas DVD-6861 3 Tenors DVD-6822 Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers: Live in '58 DVD-1598 8 Mile DVD-1639 Art of Conducting: Legendary Conductors of a Golden DVD-7689 Era (PAL) Abduction from the Seraglio (Mei) DVD-1125 Art of Piano: Great Pianists of the 20th Century DVD-2364 Abduction from the Seraglio (Schafer) DVD-1187 Art of the Duo DVD-4240 DVD-1131 Astor Piazzolla: The Next Tango DVD-4471 Abstronic VHS-1350 Atlantic Records: The House that Ahmet Built DVD-3319 Afghan Star DVD-9194 Awake, My Soul: The Story of the Sacred Harp DVD-5189 African Culture: Drumming and Dance DVD-4266 Bach Performance on the Piano by Angela Hewitt DVD-8280 African Guitar DVD-0936 Bach: Violin Concertos DVD-8276 Aida (Domingo) DVD-0600 Badakhshan Ensemble: Song and Dance from the Pamir DVD-2271 Mountains Alim and Fargana Qasimov: Spiritual Music of DVD-2397 Ballad of Ramblin' Jack DVD-4401 Azerbaijan All on a Mardi Gras Day DVD-5447 Barbra Streisand: Television Specials (Discs 1-3)