Program for Martian Highlands Workshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Archaeology and Paleoclimate of the Mud Lake Basin, Nye County, Nevada

University of Nevada, Reno Changing Landscapes During the Terminal Pleistocene/Early Holocene: The Archaeology and Paleoclimate of the Mud Lake Basin, Nye County, Nevada A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Anthropology By Lindsay A. Fenner Dr. Geoffrey M. Smith/Thesis Advisor May, 2011 © by Lindsay A. Fenner 2011 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by LINDSAY A. FENNER entitled Changing Landscapes During The Terminal Pleistocene/Early Holocene: The Archaeology And Paleoclimate Of The Mud Lake Basin, Nye County, Nevada be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Geoffrey M. Smith, Ph.D., Advisor Gary Haynes, Ph.D., Committee Member Kenneth D. Adams, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Associate Dean, Graduate School May, 2011 i ABSTRACT Archaeological investigation along Pleistocene lakeshores is a longstanding and common approach to prehistoric research in the Great Basin. Continuing in this tradition, this thesis considers the archaeological remains present from pluvial Mud Lake, Nye County, Nevada coupled with an examination of paleoclimatic conditions to assess land-use patters during the terminal Pleistocene/early Holocene. Temporally diagnostic lithic assemblages from 44 localities in the Mud Lake basin provide the framework for which environmental proxy records are considered. Overwhelmingly occupied by Prearchaic groups, comprising 76.6% of all diagnostic artifacts present, Mud Lake was intensively utilized right up to its desiccation after the Younger Dryas, estimated at 9,000 radiocarbon years before present. Intermittently occupied through the remainder of the Holocene, different land-use strategies were employed as a result of shifting subsistence resources reacting to an ever changing environment. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Southern California

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Southern California Climate and Vegetation Over the Past 125,000 Years from Lake Sequences in the San Bernardino Mountains A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography by Katherine Colby Glover 2016 © Copyright by Katherine Colby Glover 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Southern California Climate and Vegetation Over the Past 125,000 Years from Lake Sequences in the San Bernardino Mountains by Katherine Colby Glover Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Glen Michael MacDonald, Chair Long sediment records from offshore and terrestrial basins in California show a history of vegetation and climatic change since the last interglacial (130,000 years BP). Vegetation sensitive to temperature and hydroclimatic change tended to be basin-specific, though the expansion of shrubs and herbs universally signalled arid conditions, and landscpe conversion to steppe. Multi-proxy analyses were conducted on two cores from the Big Bear Valley in the San Bernardino Mountains to reconstruct a 125,000-year history for alpine southern California, at the transition between mediterranean alpine forest and Mojave desert. Age control was based upon radiocarbon and luminescence dating. Loss-on-ignition, magnetic susceptibility, grain size, x-ray fluorescence, pollen, biogenic silica, and charcoal analyses showed that the paleoclimate of the San Bernardino Mountains was highly subject to globally pervasive forcing mechanisms that register in northern hemispheric oceans. Primary productivity in Baldwin Lake during most of its ii history showed a strong correlation to historic fluctuations in local summer solar radiation values. -

Death Valley National Park

COMPLIMENTARY $3.95 2019/2020 YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE PARKS DEATH VALLEY NATIONAL PARK ACTIVITIES • SIGHTSEEING • DINING • LODGING TRAILS • HISTORY • MAPS • MORE OFFICIAL PARTNERS T:5.375” S:4.75” PLAN YOUR VISIT WELCOME S:7.375” In T:8.375” 1994, Death Valley National SO TASTY EVERYONE WILL WANT A BITE. Monument was expanded by 1.3 million FUN FACTS acres and redesignated a national park by the California Desert Protection Act. Established: Death Valley became a The largest national park below Alaska, national monument in 1933 and is famed this designation helped focus protection for being the hottest, lowest and driest on one the most iconic landscapes in the location in the country. The parched world. In 2018 nearly 1.7 million people landscape rises into snow-capped mountains and is home to the Timbisha visited the park, a new visitation record. Shoshone people. Death Valley is renowned for its colorful Land Area: The park’s 3.4 million acres and complex geology. Its extremes of stretch across two states, California and elevation support a great diversity of life Nevada. and provide a natural geologic museum. Highest Elevation: The top of This region is the ancestral homeland Telescope Peak is 11,049 feet high. The of the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe. The lowest is -282 feet at Badwater Basin. Timbisha established a life in concert Plants and Animals: Death Valley with nature. is home to 51 mammal species, 307 Ninety-three percent of the park is bird species, 36 reptile species, two designated wilderness, providing unique amphibian species and five fish species. -

5 Day Itinerary

by a grant from Travel Nevada. Travel from grant a by possible made brochure This JUST 98 MILES NORTH OF LAS VEGAS ON HIGHWAY 95. HIGHWAY ON VEGAS LAS OF NORTH MILES 98 JUST www.beattynevada.org Ph: 1.866.736.3716 Ph: Studio 401 Arts & Salon & Arts 401 Studio Mama’s Sweet Ice Sweet Mama’s Smash Hit Subs Hit Smash VFW Chow VFW Smokin’ J’s BBQ J’s Smokin’ shoot out or two performed by our local cowboys. cowboys. local our by performed two or out shoot Gema’s Café Gema’s historical area you might catch a glimpse of a a of glimpse a catch might you area historical Death Valley Coffee Time Coffee Valley Death of our local eateries. If you are in the downtown downtown the in are you If eateries. local our of Roadhouse 95 Roadhouse After your day trips into the Valley, relax at one one at relax Valley, the into trips day your After Sourdough Saloon & Eatery & Saloon Sourdough lunch at Beatty’s Cottonwood Park. Park. Cottonwood Beatty’s at lunch Hot Stuff Pizza Stuff Hot Store or enjoy walking your dog or having a picnic picnic a having or dog your walking enjoy or Store Mel’s Diner Mel’s Town, the Famous Death Valley Nut and Candy Candy and Nut Valley Death Famous the Town, Happy Burro Chili & Beer & Chili Burro Happy open daily from 10 am to 3 pm, Rhyolite Ghost Ghost Rhyolite pm, 3 to am 10 from daily open The Death Valley Nut & Candy Store Candy & Nut Valley Death The can find in our little town, the Beatty Museum, Museum, Beatty the town, little our in find can LOCAL SHOPS & EATERIES & SHOPS LOCAL Day area, be sure to visit the unique businesses that you you that businesses unique the visit to sure be area, BEATTY Between trips to explore the Death Valley Valley Death the explore to trips Between your plan for each day, and set up a check in time. -

Death Valley National Monument

DEATH VALLEY NATIONAL MONUMENT D/ETT H VALLEY NATIONAL 2 OPEN ALL YEAR o ^^uJv^/nsurty 2! c! Contents 2 w Scenic Attractions 2 2! Suggested Trips in Death Valley 4 H History 7 Indians 8 Wildlife 9 Plants 12 Geology 18 How To Reach Death Valley 23 By Automobile 23 By Airplane, Bus, or Railroad 24 Administration 25 Naturalist Service 25 Free Public Campground 25 Accommodations 25 References 27 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR- Harold L. Ickes, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Arno B. Cammerer, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON EATH VALLEY National Monument was created by Presidential proclamation on 2February 11), 1933, and enlarged to its present dimensions on March 26, 1937. Embracing 2,981 square miles, or nearly 2 million acres of primitive, unspoiled desert country, it is the second largest area administered by the National Park Service in the United States proper. Famed as the scene of a tragic episode in the gold-rush drama of '49, Death Valley has long been known to scientist and layman alike as a region rich in scientific and human interest. Its distinctive types of scenery, its geological phenomena, its flora, and climate are not duplicated by any other area open to general travel. In all ways it is different and unique. The monument is situated in the rugged desert region lying east of the High Sierra in eastern California and southwestern Nevada. The valley itself is about 140 miles in length, with the forbidding Panamint Range forming the western wall, and the precipitous slopes of the Funeral Range bounding it on the east. -

Fossil Birds from Manix Lake California

Fossil Birds From Manix Lake California By HILDEGARDE HOWARD A SHORTER CONTRIBUTION TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 264-J Descriptions of late Pleistocene bira remains, including a new species offlamingo UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1955 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 40 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract--__-_-----___-__-__-_--___________________ 199 Description of specimens—Continued Introduction _______________________________________ 199 Branta canadensis (Linnaeus)_--____--_____-_-___- 203 Description of specimens_____________________________ 201 Nyroca valisineria (Wilson) ?____________________- 203 Aechmophorus occidentalis (Lawrence)_____________ 201 Erismatura jamaicensis (Gmelin)__________________ 204 Pelecanus erythrorhynchos Gmelin_________________ 202 Aquila chrysaetos (Linnaeus)_____________________ 204 Phalacrocorax auritus (Lesson) ?_________________ 202 (?rws?_______________-_-______-____-_--__- 204 Ciconia maltha Miller_____.______________________ 202 Family Phalaropodidae__________________________ 204 Phoenicopterus copei Shufeldt?_.__________________ 202 Summary and conclusions__________________________ 204 Phoenicopterus minutus Howard, new species_ ______ 202 Literature cited___________________________________ 205 ILLUSTRATIONS PLATE 50. Phoenicopterus minutus Howard, new -

Sustaining the Legacies: Mining and Death Valley

Volume 61 Issue 3 Fall 2016 Sustaining the Legacies: Mining and Death Valley eath Valley entered my radar about ive years ago when I By Nathan Francis, Board Chair DVNHA Dmoved to the region to work as land manager for Rio Tinto Minerals (U.S. Borax). Until then, I admit it had not been on my College of Mines and Earth Sciences to show them irst-hand the bucket list of places to visit. But as my knowledge about the area region’s legacy of mining. It is my job at Rio Tinto, speciically, to grew, so did my passion for everything it ofers — including its ensure the company’s mining legacy sites in the area are safe and rich history and culture. sustainable. As this year’s board chair of the Death Valley Natural History Association, I am honored and privileged to broaden that People outside of the mining industry are often surprised at role and my support of this national treasure. how intertwined the company’s history is with that of America’s national parks, and particularly Death Valley. In fact, they are very Certainly, my interest in the Death Valley area goes beyond my closely aligned. professional role. My wife and I often explore the region with our four sons. Some of our favorite spots include Ash Meadows It was in Death Valley that the Paciic Coast Borax Company got National Wildlife Refuge, the mesquite lat dunes, Golden its start in the late 1800s. The company eventually became U.S. Canyon, and the salt lats at Badwater. -

The Pueblo in the Mojave Sink: an Archaeological Myth

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 The pueblo in the Mojave Sink: An archaeological myth Barbara Ann Loren-Webb Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Loren-Webb, Barbara Ann, "The pueblo in the Mojave Sink: An archaeological myth" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2107. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2107 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PUEBLO IN THE MOJAVE SINK: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL MYTH A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies by Barbara Ann Loren-Webb March 2003 THE PUEBLO IN THE MOJAVE SINK: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL MYTH A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Barbara Ann Loren-Webb March 2003 Approved by: Russell Barber, Chair, Anthropology Date Pete Robertshesw, Anthropology ABSTRACT In 1929 Malcolm Rogers published a paper in which he stated that there was evidence of an Anasazi or Puebloan settlement or pueblo, in the Mojave Sink Region of the Mojave Desert. Since then, archaeologists have cited Rogers' publication and repeated his claim that such a pueblo was located in the Western Mojave Desert. The purpose of this thesis started out as a review of the existing evidence and to locate this pueblo. -

Geology and Soils

3.7 GEOLOGY AND SOILS This section of the Program Environmental Impact Report (PEIR) describes the geological characteristics of the SCAG region, identifies the regulatory framework with respect to laws and regulations that govern geology and soils, and analyzes the significance of the potential impacts that could result from development of the Connect SoCal Plan (“Connect SoCal”; “Plan”). In addition, this PEIR provides regional-scale mitigation measures as well as project-level mitigation measures to be considered by lead agencies for subsequent, site-specific environmental review to reduce identified impacts as appropriate and feasible. Information regarding paleontological resources was largely obtained from the Paleontological Resources Report prepared by SWCA and included as Appendix 3.7 of this PEIR. 3.7.1 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING 3.7.1.1 Definitions Alluvium: An unconsolidated accumulation of stream deposited sediments, including sands, silts, clays or gravels. Extrusive Igneous Rocks: Rocks that crystallize from molten magma on earth’s surface. Fault: A fracture or fracture zone in rock along which movement has occurred. Formation: A laterally continuous rock unit with a distinctive set of characteristics that make it possible to recognize and map from one outcrop or well to another. The basic rock unit of stratigraphy. Holocene: An interval of time relating to, or denoting the present epoch, which is the second epoch in the Quaternary period, from approximately 11,000 years ago to the present time. Liquefaction: The process by which water-saturated sandy soil materials lose strength and become susceptible to failure during strong ground shaking in an earthquake. The shaking causes the pore-water pressure in the soil to increase, thus transforming the soil from a stable solid to a more liquid form. -

Zzyzx Mineral Springs— Cultural Treasure and Endangered Species Aquarium

Cultural and Natural Resources: Conflicts and Opportunities for Cooperation Zzyzx Mineral Springs— Cultural Treasure and Endangered Species Aquarium Danette Woo, Mojave National Preserve, 222 East Main Street, Suite 202, Barstow, California 92311; [email protected] Debra Hughson, Mojave National Preserve, 222 East Main Street, Suite 202, Barstow, California 92311; [email protected] A Brief History of Zzyzx Human use has been documented at Soda Dry Lake back to the early predecessors of the Mohave and Chemehuevi native peoples, who occupied the land when the Spanish explorers first explored the area early in the 19th century. Soda Springs lies in the traditional range of the Chemehuevi, who likely used and modified the area in pursuit of their hunter–gatherer econo- my.Trade routes existed between the coast and inland to the Colorado River and beyond for almost as long as humans have occupied this continent. These routes depended on reliable springs, spaced no more than a few days’ walk apart, and Soda Springs has long been a reliable oasis in a dehydrated expanse. The first written record of Soda Springs Soda Springs, dubbed “Hancock’s Redoubt” comes from the journals of Jedediah Strong for Winfield Scott Hancock, the Army Smith, written in 1827 when he crossed Soda Quartermaster in Los Angeles at the time. The Lake on his way to Mission San Gabriel. Army’s presence provided a buffer between Smith was the first American citizen to enter the emigrants from the East and dispossessed California by land. He crisscrossed the west- natives. California miners also traveled the ern half of the North American continent by Mojave Road on their way to the Colorado foot and pack animal from 1822 until he was River in 1861. -

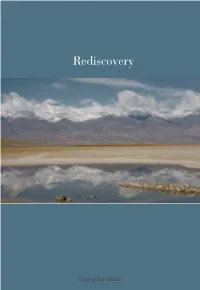

The California Deserts: an Ecological Rediscovery

3Pavlik-Ch1 10/9/07 6:43 PM Page 15 Rediscovery Copyrighted Material 3Pavlik-Ch1 10/9/07 6:43 PM Page 16 Copyrighted Material 3Pavlik-Ch1 10/9/07 6:43 PM Page 17 Indians first observed the organisms, processes, and history of California deserts. Over millennia, native people obtained knowledge both practical and esoteric, necessitated by survival in a land of extremes and accumulated by active minds recording how nature worked. Such knowledge became tradition when passed across generations, allowing cul- tural adjustments to the changing environment. The depth and breadth of their under- standing can only be glimpsed or imagined, but should never be minimized. Indians lived within deserts, were born, fed, and raised on them, su¤ered the extremes and uncertainties, and passed into the ancient, stony soils. Theirs was a discovery so intimate and spiritual, so singular, that we can only commemorate it with our own 10,000-year-long rediscov- ery of this place and all of its remarkable inhabitants. Our rediscovery has only begun. Our rediscovery is not based upon living in the deserts, despite a current human pop- ulation of over one million who dwelling east of the Sierra. We do not exist within the ecological context of the land. We are not dependant upon food webs of native plants and [Plate 13] Aha Macav, the Mojave people, depicted in 1853. (H. B. Molhausen) REDISCOVERY • 17 Copyrighted Material 3Pavlik-Ch1 10/9/07 6:43 PM Page 18 Gárces 1776 Kawaiisu Tribal groups Mono Mono Tribe Lake Aviwatha Indian place name Paiute Inyo Owens Valley -

Endogenic Carbonate Sedimentation in Bear Lake, Utah and Idaho, Over the Last Two Glacial-Interglacial Cycles

The Geological Society of America Special Paper 450 2009 Endogenic carbonate sedimentation in Bear Lake, Utah and Idaho, over the last two glacial-interglacial cycles Walter E. Dean U.S. Geological Survey, Box 25046, MS 980 Federal Center, Denver, Colorado 80225, USA ABSTRACT Sediments deposited over the past 220,000 years in Bear Lake, Utah and Idaho, are predominantly calcareous silty clay, with calcite as the dominant carbonate min- eral. The abundance of siliciclastic sediment indicates that the Bear River usually was connected to Bear Lake. However, three marl intervals containing more than 50% CaCO3 were deposited during the Holocene and the last two interglacial intervals, equivalent to marine oxygen isotope stages (MIS) 5 and 7, indicating times when the Bear River was not connected to the lake. Aragonite is the dominant mineral in two of these three high-carbonate intervals. The high-carbonate, aragonitic intervals coincide with warm interglacial continental climates and warm Pacifi c sea-surface tempera- tures. Aragonite also is the dominant mineral in a carbonate-cemented microbialite mound that formed in the southwestern part of the lake over the last several thousand years. The history of carbonate sedimentation in Bear Lake is documented through the study of isotopic ratios of oxygen, carbon, and strontium, organic carbon content, CaCO3 content, X-ray diffraction mineralogy, and HCl-leach chemistry on samples from sediment traps, gravity cores, piston cores, drill cores, and microbialites. Sediment-trap studies show that the carbonate mineral that precipitates in the surface waters of the lake today is high-Mg calcite. The lake began to precipitate high- Mg calcite sometime in the mid–twentieth century after the artifi cial diversion of Bear River into Bear Lake that began in 1911.