Special Issue in Memory of Howard B. Eisenberg Marquette University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF File Created from a TIFF Image by Tiff2pdf

JOBNAME: Morgan Stanley/Case PAGE: 1 SESS: 36 OUTPUT: Tue May 28 16:10:55 2002 − /joshuawanda 0/fin/nyork/51043/cov V NEW ISSUE — BOOK ENTRY ONLY In the opinion of Squire, Sanders & Dempsey L.L.P., Bond Counsel, under existing law, (i) assuming compliance with certain covenants and the accuracy of certain representations, interest on the Bonds is excluded from gross income for federal income tax purposes, and is not an item of tax preference for purposes of the federal alternative minimum tax imposed on individuals and corporations and (ii) interest on, and any profit made on the sale, exchange or other disposition of, the Bonds are exempt from the Ohio personal income tax, the net income base of the Ohio corporate franchise tax, and municipal and school district income taxes in Ohio. Interest on the Bonds may be subject to certain federal taxes imposed only on certain corporations, including the corporate alternative minimum tax on a portion of that interest. For a more complete discussion of the tax aspects, see ‘‘Tax Matters’’ herein. $100,000,000 STATE OF OHIO HIGHER EDUCATIONAL FACILITY REVENUE BONDS (CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY 2002 PROJECT) $64,875,000 Series A $35,125,000 Series B (Variable Rate) (Fixed Rate) The Series A Bonds and Series B Bonds, when, as and if issued, will be special obligations of the State of Ohio issued by the Ohio Higher Educational Facility Commission (the ‘‘Commission’’) pursuant to two separate Trust Agreements, dated as of May 15, 2002 (the ‘‘Series A Trust Agreement’’ and ‘‘Series B Trust Agreement’’, respectively), between the Commission and J.P. -

After a Sold-Out Run at East to Edinburgh, the WAITING GAME Returns to 59E59 Theaters

After a sold-out run at East to Edinburgh, THE WAITING GAME returns to 59E59 Theaters New York, New York January 2, 2019 —59E59 Theaters (Val Day, Artistic Director; Brian Beirne, Managing Director) is thrilled to welcome THE WAITING GAME, written by Charles Gershman and directed by Nathan Wright. Produced by Snowy Owl, THE WAITING GAME begins performances on Wednesday, February 6 for a limited engagement through Sunday, February 23. Press Opening is Tuesday, February 12 at 7:30 PM. The performance schedule is Tuesday – Saturday at 7:30 PM; and Sunday at 2:30 PM. Performances are at 59E59 Theaters (59 East 59th Street, between Park and Madison). Single tickets are $25 ($20 for 59E59 Members). Tickets are available by calling the 59E59 Box Office on 646-892-7999 or by visiting www.59e59.org. Sam's in a coma. Paolo's doing his best. When Geoff reveals a secret, reality and fantasy blur. This NYC premiere from critically acclaimed Snowy Owl follows a sold-out, award-winning run in the Edinburgh Fringe (Best Overseas Play, Derek Awards) and explores relationships in the digital age. After selling out at 59E59 Theaters’ East to Edinburgh festival, THE WAITING GAME went on to the 2017 Edinburgh Fringe where it was called "one of the Top 5 LGBTQ Shows to see in the Edinburgh Fringe" by Huffington Post. The cast features Joshua Bouchard (Séance on a Wet Afternoon at Lincoln Center/New York City Opera); Julian Joseph (Bluebloods on CBS); Ibsen Santos (Inside The Wild Heart with Group.BR); and Marc Sinoway (LOGO’s Hunting Season). -

Parziale Diss FINAL Aug 7 13

Representations of Trauma in Contemporary American Literature and Film: Moving from Erasure to Creative Transformation Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Parziale, Amy Elizabeth Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 13:06:35 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/301676 REPRESENTATIONS OF TRAUMA IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN LITERATURE AND FILM: MOVING FROM ERASURE TO CREATIVE TRANSFORMATION by Amy Elizabeth Parziale _____________________ Copyright © Amy Elizabeth Parziale 2013 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2013 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Amy Parziale entitled Representations of Trauma in Contemporary American Literature and Film: Moving from Erasure to Creative Transformation and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________Date: 4/5/2013 Susan White ___________________________________________________________Date: 4/5/2013 Sandra Soto ___________________________________________________________Date: 4/5/2013 Charles Scruggs Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

2020-22 GRADUATE CATALOG | Eastern New Mexico University

2020-22 TABLE OF CONTENTS University Notices..................................................................................................................2 About Eastern New Mexico University ...........................................................................3 About the Graduate School of ENMU ...............................................................................4 ENMU Academic Regulations And Procedures ........................................................... 5 Program Admission .............................................................................................................7 International Student Admission ...............................................................................8 Degree and Non-Degree Classification ......................................................................9 FERPA ................................................................................................................................. 10 Graduate Catalog Graduate Program Academic Regulations and Procedures ......................................................11 Thesis and Non-Thesis Plan of Study ......................................................................11 Graduation ..........................................................................................................................17 Graduate Assistantships ...............................................................................................17 Tuition and Fees ................................................................................................................... -

Space Opera 2005…………………………..……………………

presents Music and Libretto by David Bass Directed by David Bass and Amanda Jack Choreography by Deborah Mason The King Open School Cambridge, Massachusetts March 12, 13, 19, and 20, 2005 2 55 somewheresomewhere in somerville, in thereSomer- is a store that somewhere claims to in have somerville, over a thousandthere is a beersstore ville, in that stock, claims therehard to tohave find isover kegs, a a thousandstore a world-wide beers selection that in stock, claims of hard wines, to find and to kegs, liquor have a world-widefor any over party. selection of wines, and liquor for any party. thea musicthousand is always fresh, beers and they’re open the music is always fresh, and they’re open seven in stock,days a week. hard where to is this find elusive store?seven days davis a week.square. where what is is this the elusive name kegs, store? davis a world square. what-wide is the name of of this this intoxicating intoxicating paradise?paradise? selection DOWNTOWN WINE of & SPIRITS. wines, 225 elmand st. DOWNTOWN WINE & SPIRITS. 225 elm st. “we’re not your average package store.” “we’re “we’re not yournot average your package average store.” 54 3 58 58 33 Contents Space Opera 2005…………………………..…………………….. 11 Mission Statement Synopsis………………………………………………………………. 12 The North Cambridge Family Opera Company began as an Song List………………………………………………………….. 14-15 informal group of children and adults who gathered to per- form at the NoCA (North Cambridge All Arts) open studios Cast Lists, First Weekend……………………………………..16-18 weekend in May 1999. We found the experience of singing opera to be a unique way to strengthen families, to build Cast Lists, Second Weekend………….…..………………...20-22 friendships, and to enhance relationships between genera- tions. -

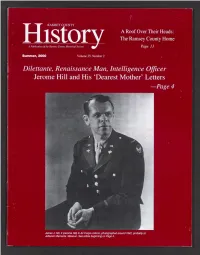

Jerome Hill and His 'Dearest Mother'

RAMSEY COUNTY A Roof Over Their Heads: The Ramsey County Home A Publication of the Ramsey County Historical Society Page 13 Summer, 2000 Volume 35, Number 2 Dilettante, Renaissance Man, Intelligence Officer Jerome Hill and His ‘Dearest Mother’ Letters —Page 4 Jam es J. Hill, Il (Jerome HUI) in Air Corps uniform, photographed around 1942, probably at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri. See article beginning on Page 4. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY Executive Director Priscilla Farnham Editor Virginia Brainard Kunz RAMSEY COUNTY Volume 35, Number 2 Summer, 2000 HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF DIRECTORS Laurie A. Zenner CONTENTS Chair Howard M. Guthmann 3 Letters President James Russell 4 Dilettante, Renaissance Man, Intelligence Officer First Vice President Jerome Hill and His World War II Letters from Anne Cowie Wilson Second Vice President France to His ‘Dearest Mother’ Richard A. Wilhoit G. Richard Slade Secretary Ronald J. Zweber 13 A Roof Over Their Heads Treasurer The History of the Old Ramsey County ‘Poor Farm’ W. Andrew Boss, Peter K. Butler, Charlotte H. Drake, Mark G. Eisenschenk, Joanne A. Englund, Pete Boulay Robert F. Garland, John M. Harens, Judith Frost Lewis, John M. Lindley, George A. Mairs, Mar 20 Plans for Preserving ‘Potters’ Field’— Heritage of the lene Marschall, Richard T. Murphy, Sr., Linda Owen, Marvin J. Pertzik, Vicenta D. Scarlett, Public Welfare System Glenn Wiessner. Robert C. Vogel EDITORIAL BOARD 22 Recounting the 1962 Recount John M. Lindley, chair; James B. Bell, Thomas H. Boyd, Thomas C. Buckley, Pat Hart, Virginia The Closest Race for Governor in Minnesota’s History Brainard Kunz, Thomas J. Kelley, Tom Mega, Laurie Murphy, Vicenta Scarlett, G. -

American Music Research Center Journal

AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER JOURNAL Volume 19 2010 Paul Laird, Guest Co-editor Graham Wood, Guest Co-editor Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder THE AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Mary Dominic Ray, O.P. (1913–1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music William S. Farley, Research Assistant, 2009–2010 K. Dawn Grapes, Research Assistant, 2009–2011 EDITORIAL BOARD C. F. Alan Cass Kip Lornell Susan Cook Portia Maultsby Robert R. Fink Tom C. Owens William Kearns Katherine Preston Karl Kroeger Jessica Sternfeld Paul Laird Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Victoria Lindsay Levine Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25.00 per issue ($28.00 outside the U.S. and Canada). Please address all inquiries to Lisa Bailey, American Music Research Center, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. E-mail: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISSN 1058-3572 © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing articles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and pro- posals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (excluding notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, University of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

Table of Contents for Volume 89, Number 1 Marquette University

Marquette Law Review Volume 89 Article 1 Issue 1 Symposium: The Brown Conferences Table of Contents for Volume 89, Number 1 Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Marquette University, Table of Contents for Volume 89, Number 1, 89 Marq. L. Rev. (2005). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol89/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW Volume 89 Fall 2005 Number 1 SYMPOSIUM: THE BROWN CONFERENCES REFLECTIONS ON WISCONSIN'S BROWN EXPERIENCE Phoebe Weaver W illiams ................................................................. 1 THE CONUNDRUM OF SEGREGATION'S ENDING: THE EDUCATION CHOICES A lison B arnes................................................................................. 33 BROWN: WHY WE MUST REMEMBER Mildred Wigfall Robinson ............................................................ 53 SOME CONDITIONS IN MILWAUKEE AT THE TIME OF BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION Frank Z eidler................................................................................ 75 THE MILWAUKEE CASES Irvin B . Charne.............................................................................. 83 EDUCATION OF AMERICAN INDIANS IN THE AGE OF BROWN -

Xerox University Microfilms

SKEPTICISM AND DOCTRINE IN THE WORKS OF CYRANO DE BERGERAC (1619--1655) Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Johnson, Charles Richard, 1927- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 06:30:47 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288336 INFORMATION TC USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. -

Jack Oakie & Victoria Horne-Oakie Films

JACK OAKIE & VICTORIA HORNE-OAKIE FILMS AVAILABLE FOR RESEARCH VIEWING To arrange onsite research viewing access, please visit the Archive Research & Study Center (ARSC) in Powell Library (room 46) or e-mail us at [email protected]. Jack Oakie Films Close Harmony (1929). Directors, John Cromwell, A. Edward Sutherland. Writers, Percy Heath, John V. A. Weaver, Elsie Janis, Gene Markey. Cast, Charles "Buddy" Rogers, Nancy Carroll, Harry Green, Jack Oakie. Marjorie, a song-and-dance girl in the stage show of a palatial movie theater, becomes interested in Al West, a warehouse clerk who has put together an unusual jazz band, and uses her influence to get him a place on one of the programs. Study Copy: DVD3375 M The Wild Party (1929). Director, Dorothy Arzner. Writers, Samuel Hopkins Adams, E. Lloyd Sheldon. Cast, Clara Bow, Fredric March, Marceline Day, Jack Oakie. Wild girls at a college pay more attention to parties than their classes. But when one party girl, Stella Ames, goes too far at a local bar and gets in trouble, her professor has to rescue her. Study Copy: VA11193 M Street Girl (1929). Director, Wesley Ruggles. Writer, Jane Murfin. Cast, Betty Compson, John Harron, Ned Sparks, Jack Oakie. A homeless and destitute violinist joins a combo to bring it success, but has problems with her love life. Study Copy: VA8220 M Let’s Go Native (1930). Director, Leo McCarey. Writers, George Marion Jr., Percy Heath. Cast, Jack Oakie, Jeanette MacDonald, Richard “Skeets” Gallagher. In this comical island musical, assorted passengers (most from a performing troupe bound for Buenos Aires) from a sunken cruise ship end up marooned on an island inhabited by a hoofer and his dancing natives. -

THE ETHICAL DILEMMA of SCIENCE and OTHER WRITINGS the Rockefeller Institute Press

THE ETHICAL DILEMMA OF SCIENCE AND OTHER WRITINGS The Rockefeller Institute Press IN ASSOCIATION WITH OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK 1960 @ 1960 BY THE ROCKEFELLER INSTITUTE PRESS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY THE ROCKEFELLER INSTITUTE PRESS IN ASSOCIATION WITH OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 60-13207 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE The Ethical Dilemma of Science Living mechanism 5 The present tendencies and the future compass of physiological science 7 Experiments on frogs and men 24 Scepticism and faith 39 Science, national and international, and the basis of co-operation 45 The use and misuse of science in government 57 Science in Parliament 67 The ethical dilemma of science 72 Science and witchcraft, or, the nature of a university 90 CHAPTER TWO Trailing One's Coat Enemies of knowledge 105 The University of London Council for Psychical Investigation 118 "Hypothecate" versus "Assume" 120 Pharmacy and Medicines Bill (House of Commons) 121 The social sciences 12 5 The useful guinea-pig 127 The Pure Politician 129 Mugwumps 131 The Communists' new weapon- germ warfare 132 Independence in publication 135 ~ CONTENTS CHAPTER THREE About People Bertram Hopkinson 1 39 Hartley Lupton 142 Willem Einthoven 144 The Donnan-Hill Effect (The Mystery of Life) 148 F. W. Lamb 156 Another Englishman's "Thank you" 159 Ivan P. Pavlov 160 E. D. Adrian in the Chair of Physiology at Cambridge 165 Louis Lapicque 168 E. J. Allen 171 William Hartree 173 R. H. Fowler 179 Joseph Barcroft 180 Sir Henry Dale, the Chairman of the Science Committee of the British Council 184 August Krogh 187 Otto Meyerhof 192 Hans Sloane 195 On A.