Professor John P. Bakke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boxoffice Records: Season 1937-1938 (1938)

' zm. v<W SELZNICK INTERNATIONAL JANET DOUGLAS PAULETTE GAYNOR FAIRBANKS, JR. GODDARD in "THE YOUNG IN HEART” with Roland Young ' Billie Burke and introducing Richard Carlson and Minnie Dupree Screen Play by Paul Osborn Adaptation by Charles Bennett Directed by Richard Wallace CAROLE LOMBARD and JAMES STEWART in "MADE FOR EACH OTHER ” Story and Screen Play by Jo Swerling Directed by John Cromwell IN PREPARATION: “GONE WITH THE WIND ” Screen Play by Sidney Howard Director, George Cukor Producer DAVID O. SELZNICK /x/HAT price personality? That question is everlastingly applied in the evaluation of the prime fac- tors in the making of motion pictures. It is applied to the star, the producer, the director, the writer and the other human ingredients that combine in the production of a motion picture. • And for all alike there is a common denominator—the boxoffice. • It has often been stated that each per- sonality is as good as his or her last picture. But it is unfair to make an evaluation on such a basis. The average for a season, based on intakes at the boxoffices throughout the land, is the more reliable measuring stick. • To render a service heretofore lacking, the publishers of BOXOFFICE have surveyed the field of the motion picture theatre and herein present BOXOFFICE RECORDS that tell their own important story. BEN SHLYEN, Publisher MAURICE KANN, Editor Records is published annually by Associated Publica- tions at Ninth and Van Brunt, Kansas City, Mo. PRICE TWO DOLLARS Hollywood Office: 6404 Hollywood Blvd., Ivan Spear, Manager. New York Office: 9 Rockefeller Plaza, J. -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Lloyd Bacon WRITING Rian James and James Seymour wrote the screenplay with contributions from Whitney Bolton, based on a novel by Bradford Ropes. PRODUCER Darryl F. Zanuck CINEMATOGRAPHY Sol Polito EDITING Thomas Pratt and Frank Ware DANCE ENSEMBLE DESIGN Busby Berkeley The film was nominated for Best Picture and Best Sound at the 1934 Academy Awards. In 1998, the National Film Preservation Board entered the film into the National Film Registry. CAST Warner Baxter...Julian Marsh Bebe Daniels...Dorothy Brock George Brent...Pat Denning Knuckles (1927), She Couldn't Say No (1930), A Notorious Ruby Keeler...Peggy Sawyer Affair (1930), Moby Dick (1930), Gold Dust Gertie (1931), Guy Kibbee...Abner Dillon Manhattan Parade (1931), Fireman, Save My Child Una Merkel...Lorraine Fleming (1932), 42nd Street (1933), Mary Stevens, M.D. (1933), Ginger Rogers...Ann Lowell Footlight Parade (1933), Devil Dogs of the Air (1935), Ned Sparks...Thomas Barry Gold Diggers of 1937 (1936), San Quentin (1937), Dick Powell...Billy Lawler Espionage Agent (1939), Knute Rockne All American Allen Jenkins...Mac Elroy (1940), Action, the North Atlantic (1943), The Sullivans Edward J. Nugent...Terry (1944), You Were Meant for Me (1948), Give My Regards Robert McWade...Jones to Broadway (1948), It Happens Every Spring (1949), The George E. -

Llyn Foulkes Between a Rock and a Hard Place

LLYN FOULKES BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE LLYN FQULKES BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE Initiated and Sponsored by Fellows ol Contemporary Art Los Angeles California Organized by Laguna Art Museum Laguna Beach California Guest Curator Marilu Knode LLYN FOULKES: BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE This book has been published in conjunction with the exhibition Llyn Foulkes: Between a Rock and a Hard Place, curated by Marilu Knode, organized by Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, California, and sponsored by Fellows of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California. The exhibition and book also were supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, Washington, D.C., a federal agency. TRAVEL SCHEDULE Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, California 28 October 1995 - 21 January 1996 The Contemporary Art Center, Cincinnati, Ohio 3 February - 31 March 1996 The Oakland Museum, Oakland, California 19 November 1996 - 29 January 1997 Neuberger Museum, State University of New York, Purchase, New York 23 February - 20 April 1997 Palm Springs Desert Museum, Palm Springs, California 16 December 1997 - 1 March 1998 Copyright©1995, Fellows of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles All rights reserved. No part of the contents of this book may be reproduced, in whole or in part, without permission from the publisher, the Fellows of Contemporary Art. Editor: Sue Henger, Laguna Beach, California Designers: David Rose Design, Huntington Beach, California Printer: Typecraft, Inc., Pasadena, California COVER: That Old Black Magic, 1985 oil on wood 67 x 57 inches Private Collection Photo Credits (by page number): Casey Brown 55, 59; Tony Cunha 87; Sandy Darnley 17; Susan Einstein 63; William Erickson 18; M. -

Book Group Brochure 2016-2017

Visit the Reading Room at Join a Group! www.mhl.org/clubs to find the 2016-2017 books in the library catalog and to All of Memorial Hall learn more about the reading Library’s book groups selections. Book are open to new Discussion members. Groups Thinking of joining? Visit one of the upcoming sessions. Registration is not required for any of the book groups. Memorial Hall Library 2 North Main St. Andover, MA 01810 Phone: 978-623-8401, x31 or 32 Memorial Hall Library E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.mhl.org 978-623-8401, x 31 or 32 www.mhl.org Sponsored by the Friends of MHL www.mhl.org/friends [email protected] Rev. 6.16 Morning Book Group Great Books Group Nonfiction Book Group The Morning Book Discussion Group The Great Books Discussion Group The Nonfiction Book Discussion Group generally meets on the third Monday of the generally meets on the fourth Tuesday of the generally meets on the first Wednesday of month at 10:30am in the Activity Room. month at 7:30pm in the Activity Room. the month at 7pm in the Activity Room. July 18, 2016 No meeting July or August July 6, 2016 The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway The Lady in Gold by Anne-Marie O’Connor August 15, 2016 September 27, 2016 August All Our Names by Dinaw Mengestu Beowulf Seamus Heaney Translation No meeting Grendel by John Gardner September 19, 2016 September 7, 2016 My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante October 25, 2016 Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson October 17, 2016 October 5, 2016 November 29, 2016 Dead Wake by Erik Larson -

Jerome Hill and His 'Dearest Mother'

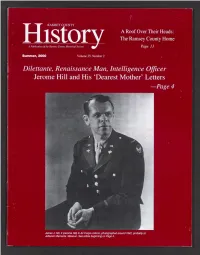

RAMSEY COUNTY A Roof Over Their Heads: The Ramsey County Home A Publication of the Ramsey County Historical Society Page 13 Summer, 2000 Volume 35, Number 2 Dilettante, Renaissance Man, Intelligence Officer Jerome Hill and His ‘Dearest Mother’ Letters —Page 4 Jam es J. Hill, Il (Jerome HUI) in Air Corps uniform, photographed around 1942, probably at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri. See article beginning on Page 4. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY Executive Director Priscilla Farnham Editor Virginia Brainard Kunz RAMSEY COUNTY Volume 35, Number 2 Summer, 2000 HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF DIRECTORS Laurie A. Zenner CONTENTS Chair Howard M. Guthmann 3 Letters President James Russell 4 Dilettante, Renaissance Man, Intelligence Officer First Vice President Jerome Hill and His World War II Letters from Anne Cowie Wilson Second Vice President France to His ‘Dearest Mother’ Richard A. Wilhoit G. Richard Slade Secretary Ronald J. Zweber 13 A Roof Over Their Heads Treasurer The History of the Old Ramsey County ‘Poor Farm’ W. Andrew Boss, Peter K. Butler, Charlotte H. Drake, Mark G. Eisenschenk, Joanne A. Englund, Pete Boulay Robert F. Garland, John M. Harens, Judith Frost Lewis, John M. Lindley, George A. Mairs, Mar 20 Plans for Preserving ‘Potters’ Field’— Heritage of the lene Marschall, Richard T. Murphy, Sr., Linda Owen, Marvin J. Pertzik, Vicenta D. Scarlett, Public Welfare System Glenn Wiessner. Robert C. Vogel EDITORIAL BOARD 22 Recounting the 1962 Recount John M. Lindley, chair; James B. Bell, Thomas H. Boyd, Thomas C. Buckley, Pat Hart, Virginia The Closest Race for Governor in Minnesota’s History Brainard Kunz, Thomas J. Kelley, Tom Mega, Laurie Murphy, Vicenta Scarlett, G. -

American Music Research Center Journal

AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER JOURNAL Volume 19 2010 Paul Laird, Guest Co-editor Graham Wood, Guest Co-editor Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder THE AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Mary Dominic Ray, O.P. (1913–1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music William S. Farley, Research Assistant, 2009–2010 K. Dawn Grapes, Research Assistant, 2009–2011 EDITORIAL BOARD C. F. Alan Cass Kip Lornell Susan Cook Portia Maultsby Robert R. Fink Tom C. Owens William Kearns Katherine Preston Karl Kroeger Jessica Sternfeld Paul Laird Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Victoria Lindsay Levine Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25.00 per issue ($28.00 outside the U.S. and Canada). Please address all inquiries to Lisa Bailey, American Music Research Center, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. E-mail: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISSN 1058-3572 © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing articles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and pro- posals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (excluding notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, University of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. -

Orientalist Commercializations: Tibetan Buddhism in American Popular Film

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 2 Issue 2 October 1998 Article 5 October 1998 Orientalist Commercializations: Tibetan Buddhism in American Popular Film Eve Mullen Mississippi State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Mullen, Eve (1998) "Orientalist Commercializations: Tibetan Buddhism in American Popular Film," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol2/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Orientalist Commercializations: Tibetan Buddhism in American Popular Film Abstract Many contemporary American popular films are presenting us with particular views of Tibetan Buddhism and culture. Unfortunately, the views these movies present are often misleading. In this essay I will identify four false characterizations of Tibetan Buddhism, as described by Tibetologist Donald Lopez, characterizations that have been refuted by post-colonial scholarship. I will then show how these misleading characterizations make their way into three contemporary films, Seven Years in Tibet, Kundun and Little Buddha. Finally, I will offer an explanation for the American fascination with Tibet as Tibetan culture is represented in these films. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol2/iss2/5 Mullen: Orientalist Commercializations Tibetan religion and culture are experiencing an unparalleled popularity. Tibetan Buddhism and Tibetan history are commonly the subjects of Hollywood films. -

RESISTANCE MADE in HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945

1 RESISTANCE MADE IN HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945 Mercer Brady Senior Honors Thesis in History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of History Advisor: Prof. Karen Hagemann Co-Reader: Prof. Fitz Brundage Date: March 16, 2020 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank Dr. Karen Hagemann. I had not worked with Dr. Hagemann before this process; she took a chance on me by becoming my advisor. I thought that I would be unable to pursue an honors thesis. By being my advisor, she made this experience possible. Her interest and dedication to my work exceeded my expectations. My thesis greatly benefited from her input. Thank you, Dr. Hagemann, for your generosity with your time and genuine interest in this thesis and its success. Thank you to Dr. Fitz Brundage for his helpful comments and willingness to be my second reader. I would also like to thank Dr. Michelle King for her valuable suggestions and support throughout this process. I am very grateful for Dr. Hagemann and Dr. King. Thank you both for keeping me motivated and believing in my work. Thank you to my roommates, Julia Wunder, Waverly Leonard, and Jamie Antinori, for being so supportive. They understood when I could not be social and continued to be there for me. They saw more of the actual writing of this thesis than anyone else. Thank you for being great listeners and wonderful friends. Thank you also to my parents, Joe and Krista Brady, for their unwavering encouragement and trust in my judgment. I would also like to thank my sister, Mahlon Brady, for being willing to hear about subjects that are out of her sphere of interest. -

2 | White-Dominated Cultural Appropriation in the Publishing Industry

2 | White-Dominated Cultural Appropriation in the Publishing Industry Zhinan Yu, Department of Communication This chapter seeks to explore cultural appropriation as a diverse, ubiquitous, and morally problematic phenomenon (Matthes, 2016, p. 344) emerging particularly in white writers’ novels. In approaching this goal, a case study based on English writer James Hilton’s best-known novel Lost Horizon (1933) will be given through addressing relevant theoretical concepts including imperialist literature, colonialism and orientalism. The case study aims at exemplifying how white-dominated cultural appropriation implemented by writer’s misuses and misperceptions toward Asian cultures. Then, in the second part of this chapter, multifaceted perspectives will be drawn into the discussion for giving cultural appropriation a further sight beyond the novel itself, and pay attention to the book publishing industry as an international yet still race-biased business in terms of globalization. Keywords: cultural appropriation; imperialist literature; white-dominated; Lost Horizon; book publishing; globalization. Introduction In a 2015 article published in The Guardian, novelist, essayist and literary critic Anjali Enjeti astutely asserted that writers of colour are “severely under-represented in the literary world”. In this piece, Enjeti chronicles a controversy over the Best American Poets 2015 anthology, wherein the volume’s editor, Sherman Alexie, decided to publish the poem “The Bees, the Flowers, Jesus, Ancient Tigers, Poseidon, Adam and Eve” despite the author’s use of a racialized pseudonym. After selecting the poem, Alexie found out that the poem’s author, Yi-Fen Chou, was actually the Chinese pseudonym for Michael Derrick Hudson, a white man from Wabash, Indiana. In his bio as Yi-Fen Chou, the author indicates that this poem was rejected 40 times under his real name, but only rejected 9 times under his pen name, and he has realized he could Copyright © 2018 Yu. -

HISTORY of the CINEMA : 1895 - 1940 / Collection De Microfiches (MF 195)

HISTORY OF THE CINEMA : 1895 - 1940 / Collection de microfiches (MF 195) Classement par auteur / collectivité AUTEUR TITRE EDITION Abramson, Ivan. Mother of truth : a story of romance and retribution based on the events [New York] : Graphic Literary Press,[c1929] of my own life. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and 1937 academy players directory bulletin. Special ed., 2nd printing, rev. Beverly Hills, Calif. : Sciences. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, c1981. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Motion picture sound engineering. New York : D. Van Nostrand Company, 1938. Sciences. Research Council. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Report on television from the standpoint of the motion picture producing Hollywood : The Academy, 1936. Sciences. Research Council. industry. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Screen achievements records bulletin. Reference list of productions. Reference list of productions 1934/38. Hollywood Sciences. :[The Academy, 1938?] Ackerman, Carl William, 1890- George Eastman / by Carl W. Ackerman ; with an introduction by Edwin London : Houghton Mifflin Co., 1930. R. A. Seligman. Adam, Thomas Ritchie, 1900- Motion pictures in adult education New York : American Association for Adult Education, 1940 Adeler, Edwin. Remember Fred Karno? : the life of a great showman London : John Long, 1939. Adler, Mortimer Jerome, 1902- Art and prudence : a study in practical philosophy New York ;Toronto : Longmans, Green and Company, 1937 Aguilar, Santiago. El genio del septimo arte : apologia de Charlot Madrid : Compania Ibero-Americana de Publicaciones, 1930. Albert, Katherine ed. How to be glamorous : expert advice from Joan Crawford, Cecil B. New York, c1936. DeMille, et al. BCUL Dorigny-Unithèque/ Cinespace/ps 1. Albert, Katherine. -

PTFF 2006 Were Shot Digitally and Edited in a Living Room Somewhere

22 00 00 00 PP TT TT FF ~~ 22 00 00 66 22 00 00 11 22 00 00 66 PP oo r r t t TT oo ww nn ss ee nn dd FF i i l l mm FF ee ss t t i i vv aa l l - - SS ee pp t t ee mmbb ee r r 11 55 - - 11 77 , , 22 00 00 66 22 00 00 22 GGrreeeettiinnggss ffrroomm tthhee DDiirreeccttoorr 22 00 00 33 It is only human to want to improve, so each year the Port Townsend Film Festival continues to tweak its programming. In what 22 00 00 44 sometimes feels like a compulsive drive to create the perfect Festival, we add things one place, subtract in another, but mostly we 22 00 00 55 just add. Since our first year in 2000, we have added to our programming, in roughly chronological order: films of topical 22 00 00 66 interest, the extension of Taylor Street Outdoor Movies to Sunday 22 00 00 77 night, Almost Midnight movies, street musicians, Formative Films, the San Francisco-based National Public Radio program West Coast 22 00 00 88 Live!, the First Features sidebar, the continuous-run Drop-In Theatre, the Kids Film Camp, and A Moveable Fest, taking four Festival films 22 00 00 99 to the Historic Lynwood Theatre on Bainbridge Island. For 2006, we're adding two more innovations 22 00 11 00 advanced tickets sales, and 22 00 11 11 the Festival's own trailer. 22 00 11 22 The Festival has often been criticized for relying on passes and last minute "rush" tickets for box 22 00 11 33 office sales, so this year the Festival is selling a limited number of advance tickets for screenings at our largest venue, the Broughton Theatre at the high school.