Exceptional Queerness: Defining the Boundaries of Normative U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MASTERCLASS Meet

MASTERCLASS Meet uPaul Charles’s chameleonic qualities have made him a television icon, spiritual guide, and R the most commercially successful drag queen in United States history. Over a nearly three-decade career, he’s ushered in a new era of visibility for drag, upended gender norms, and highlighted queer talent from across the world—all while dressed as a fierce glamazon. “Be willing to become the shape-shifter that you absolutely are.” Born in San Diego, California, RuPaul first experienced mainstream success when a dance track he wrote called “Supermodel (You Better Work)” became an unexpected MTV hit (Ru stars in the music video). The song led to a modeling contract with MAC Cosmetics and a talk show on VH1, which saw RuPaul interviewing everyone from Nirvana to the Backstreet Boys and Diana Ross to Bea Arthur. He has since appeared in more than three dozen films and TV shows, including Broad City, The Simpsons, But I’m a Cheerleader!, and To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar. RuPaul’s Drag Race, Ru’s decade-old, Emmy-winning reality drag competition, has gone international, with spin-offs set in the U.K. and Thailand. He’s also published three books: 2 RuPaul 1995’s Lettin’ It All Hang Out, 2010’s Workin’ It!, and 2018’s GuRu, which features a foreword from Jane Fonda. Recently, he became the first drag queen to land the cover of Vanity Fair. His Netflix debut, AJ and the Queen, premiered on the streaming service in January 2020. RuPaul saw drag as a tool that would guide his punk rock, anti-establishment ethos. -

Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970

Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Lvovsky, Anna. 2015. Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463142 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge about Homosexuality, 1920–1970 A dissertation presented by Anna Lvovsky to The Committee on Higher Degrees in the History of American Civilization in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of American Civilization Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 – Anna Lvovsky All rights reserved. Advisor: Nancy Cott Anna Lvovsky Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge about Homosexuality, 1920–1970 Abstract This dissertation tracks how urban police tactics against homosexuality participated in the construction, ratification, and dissemination of authoritative public knowledge about gay men in the -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan

70-14-,016 FLACK, Bruce Clayton, 19 38- THE WORK OF THE AMERICAN YOUTH COMMISSION, 1935-1942. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1969 History, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by Bruce Clayton Flack 1970 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE WORK OP THE AMERICAN YOUTH COMMISSION, 1935-19i;2 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bruce Clayton Flack, B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University Approved by ~ Adviser Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to Logan Wilson, president of the American Council on Education for permitting me to use the files of the American Youth Commission. I am grateful to Richard Young for allowing me to use the Owen D. Young Papers in Van Hornesville, New York and to Homer P. Rainey for opening to me his papers at the University of Missouri. The staffs of the National Archives and the Library of Congress were also very helpful. My adviser, Robert H. Bremner, has given patient and under standing assistance. A final word of gratitude goes to my wife, Carol, who has helped in innumerable ways. ii I VITA April 2, 1938 Born— Fremont, Ohio I960 ..... B.a ., Otterbein College, Westerville, Ohio 1962 ........ M.A., The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1963-1965 . High School Teacher, Berea City Schools, Berea, Ohio 1965-1969 . Teaching Associate, Department of History, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1969 . .... Appointment as Assistant Professor and Chairman of the Division of Social Sciences, Glenville State College, Glenville, West Virginia FIELDS OF STUDY Major Field: History Political and Social History of the United States Since 1900. -

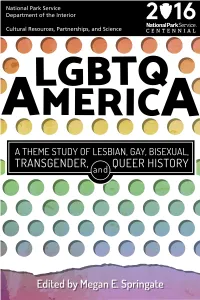

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PLACES Unlike the Themes section of the theme study, this Places section looks at LGBTQ history and heritage at specific locations across the United States. While a broad LGBTQ American history is presented in the Introduction section, these chapters document the regional, and often quite different, histories across the country. In addition to New York City and San Francisco, often considered the epicenters of LGBTQ experience, the queer histories of Chicago, Miami, and Reno are also presented. QUEEREST28 LITTLE CITY IN THE WORLD: LGBTQ RENO John Jeffrey Auer IV Introduction Researchers of LGBTQ history in the United States have focused predominantly on major cities such as San Francisco and New York City. This focus has led researchers to overlook a rich tradition of LGBTQ communities and individuals in small to mid-sized American cities that date from at least the late nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth century. -

Current Notes

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 32 | Issue 6 Article 7 1942 Current Notes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Current Notes, 32 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 646 (1941-1942) This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. CURRENT NOTES To Curb Crime During War-In order N. Pfeiffer, former President, National to meet the threat of increased crime under Probation Association; Morris Ploscowe, war conditions, the Society for the Pre- Chief Clerk, New York City Special Ses- vention of Crime, one of New York's oldest sions Court; Prof. Walter C. Reckless, Ohio agencies in this field, is establishing itself State University; Prof. Edwin H. Suther- as a national organization. land, Indiana University; Judge Joseph N. A National Advisory Council, composed Ulman, Supreme Bench of Baltimore; and of the nation's leaders in criminology and Miriam Van Waters, Superintendent, crime prevention, is being set up. All sec- Massachusetts Reformatory for Women. tions of the country will be represented. Also G. Howland Shaw, Assistant Secre- At the same time the Society announced tary of State and President, American that, in addition to its new policy of con- Prison Association; Prof. Norman S. Hay- tinuous surveys and investigations of the ner, of the State University of Washington; crime situation, a program has been Kenyon J. -

Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. INCLUSIVE STORIES Although scholars of LGBTQ history have generally been inclusive of women, the working classes, and gender-nonconforming people, the narrative that is found in mainstream media and that many people think of when they think of LGBTQ history is overwhelmingly white, middle-class, male, and has been focused on urban communities. While these are important histories, they do not present a full picture of LGBTQ history. To include other communities, we asked the authors to look beyond the more well-known stories. Inclusion within each chapter, however, isn’t enough to describe the geographic, economic, legal, and other cultural factors that shaped these diverse histories. Therefore, we commissioned chapters providing broad historical contexts for two spirit, transgender, Latino/a, African American Pacific Islander, and bisexual communities. -

LISTENING to DRAG: MUSIC, PERFORMANCE and the CONSTRUCTION of OPPOSITIONAL CULTURE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillmen

LISTENING TO DRAG: MUSIC, PERFORMANCE AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF OPPOSITIONAL CULTURE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Elizabeth Kaminski, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Vincent Roscigno, Advisor Professor Verta Taylor _________________________ Advisor Professor Nella Van Dyke Sociology Graduate Program ABSTRACT This study examines how music is utilized in drag performances to create an oppositional culture that challenges dominant structures of gender and sexuality. I situate this analysis in literature on the role of music and other cultural resources in the mobilization of social movement protest. Drawing from multiple sources of data, I demonstrate that drag queen performers make use of popular songs to build solidarity, evoke a sense of injustice, and enhance feelings of agency among audience members – three dimensions of cognition that constitute a collective action framework, conducive to social protest. The analysis is based on observations of drag performances; content analysis of the lyrics of drag songs; intensive interviews with drag queens at the 801 Cabaret in Key West, Florida; focus groups with audience members who attended the shows at the 801 Cabaret; and interviews with drag queen informants in Columbus, Ohio. I demonstrate how drag performers use music to construct new alliances and understandings of gender and sexuality among gay and heterosexual members of the audience. The data illustrate that drag performers strategically select songs to evoke an array of emotions among audience members. First are songs that utilize sympathy, sorrow, and humor to build solidarity. -

Literary Modernism, Queer Theory, and the Trans Feminine Allegory

UC Irvine FlashPoints Title The New Woman: Literary Modernism, Queer Theory, and the Trans Feminine Allegory Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/11z5g0mz ISBN 978081013 5550 Author Heaney, Emma Publication Date 2017-08-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The New Woman The FlashPoints series is devoted to books that consider literature beyond strictly national and disciplinary frameworks, and that are distinguished both by their historical grounding and by their theoretical and conceptual strength. Our books engage theory without losing touch with history and work historically without falling into uncritical positivism. FlashPoints aims for a broad audience within the humanities and the social sciences concerned with moments of cultural emergence and transformation. In a Benjaminian mode, FlashPoints is interested in how liter- ature contributes to forming new constellations of culture and history and in how such formations function critically and politically in the present. Series titles are available online at http://escholarship.org/uc/fl ashpoints. series editors: Ali Behdad (Comparative Literature and English, UCLA), Edi- tor Emeritus; Judith Butler (Rhetoric and Comparative Literature, UC Berkeley), Editor Emerita; Michelle Clayton (Hispanic Studies and Comparative Literature, Brown University); Edward Dimendberg (Film and Media Studies, Visual Studies, and European Languages and Studies, UC Irvine), Founding Editor; Catherine Gallagher (English, UC Berkeley), Editor Emerita; Nouri Gana (Comparative Lit- erature and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UCLA); Susan Gillman (Lit- erature, UC Santa Cruz), Coordinator; Jody Greene (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Richard Terdiman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz), Founding Editor A complete list of titles begins on p. -

American Women/American Womanhood: 1870S to the Present

American Women/American Womanhood: 1870s to the Present (HIUS157) Prof. Rebecca Jo Plant Winter 2010 T/TR 9:30-10:50 a.m. Center Hall, 212 Course description This course examines the history of women in the United States from roughly 1870 to the present. We will explore the status and experiences of American women from a range of perspectives _ social, cultural, political, economic and legal. A central concern will be the relationship between gender ideologies and divisions based on class and race within America society. Major areas of inquiry will include: strategies that women have employed to attain political influence and power; changing conceptions of women_s rights and duties as citizens; women_s roles as producers and consumers in an industrial and post-industrial economy; and attitudes and policies that have served to regulate female sexuality, reproduction and motherhood. Contacting Prof. Plant email: [email protected] Phone: 534-8920 Office hours: Tuesdays, noon to 2 p.m., HSS 6016 Course Requirements: The course requirements are as follows: two 3-4 page papers (25% each); the midterm (20%); and the final examination (30%). The midterm will consist of a series of short answer questions. The final will have identifications, short answer questions, and two essay questions. Answers to the identifications should be roughly two sentences and should identify the person, event, or term and briefly explain its significance. Short answer questions require a paragraph-long response. Essay responses should be roughly five-paragraphs. Policy regarding late papers: I will accept late papers without penalty only if an extension is requested by email at least seven days in advance of the due date. -

Principles of Adult Education at Work in an Early Women’S Prison: the Case of the Massachusetts Reformatory, 1930-1960

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press Adult Education Research Conference 2005 Conference Proceedings (Athens, GA) Principles of Adult Education at Work in an Early Women’s Prison: The Case of the Massachusetts Reformatory, 1930-1960 Dominique T. Chlup Texas A&M University, USA Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/aerc Part of the Adult and Continuing Education Administration Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Recommended Citation Chlup, Dominique T. (2005). "Principles of Adult Education at Work in an Early Women’s Prison: The Case of the Massachusetts Reformatory, 1930-1960," Adult Education Research Conference. https://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2005/papers/48 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Adult Education Research Conference by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Principles of Adult Education at Work in an Early Women’s Prison: The Case of the Massachusetts Reformatory, 1930-1960 Dominique T. Chlup Texas A&M University, USA Abstract: This paper discusses the role and significance of adult education principles as espoused by an early corrections official Austin MacCormick and how his philosophy and aim of adult education for prisoners relates to the educational programs and practices implemented at the Massachusetts Reformatory for Women during the 1930s, 40s, and 50s. Introduction In the field of correctional education, it is often joked that if correctional education is the “neglected child” of corrections, it is the “illegitimate child” of education (Brown-Young, 1986). -

Speak out December 2020

BHS Speak Out December 2020 Speak Out DECEMBER ISSUE – ARTS & CULTURE Drag as an Art Form Art & Lebanese Culture Movement of Surrealism Having decided that there is so In its simplest terms, drag is a Art expresses ideas which revolve around gender-bending art form by which the way we think and see ourselves. Art is much more to the human mind individuals - including cis male, non- a mirror of our world view. The Lebanese than all fields have shown, Freud binary and transgender individuals - people are hopeful and resilient has become a widely influential use clothing and makeup to individuals – having gone through the figure regarding psychoanalysis. The absurdity of the subconscious exaggerate and replicate female worst situations possible – and art features. However, as drag is one of represents that general character in its became an unfeared topic, the most misunderstood art forms, many forms. Take for example the famous whereby the human race took on a this definition only scratches the icon Fairuz whose music brought hope to newly found understanding of surface of what it’s all about (Full the Lebanese people in times of war and themselves… (Full article on page 17) article on page 3) despair. (Full article on page 14) 1 BHS Speak Out December 2020 Table of Contents Drag as an Art Form 3 Art for Activism 9 How has art been affected by Lebanese culture? 11 The Movement of Surrealism 14 Instagram polls 16 Aerial Photography in Lebanon 17 Trends in Fashion 20 Credits Poem 22 Adviser: Mr. Chadi Nakhle Editor-in-Chief: Adriana Goraieb IB2 Co-Editor: Gabriel El Khabbaz IB2 Contributors: BHS Students 2 BHS Speak Out December 2020 Drag as an Art Form GABRIEL KHABBAZ & ADRIANA GORAIEB – IB2 “We’re all born naked and the rest is drag” — RuPaul Charles What is Drag? In its simplest terms, drag is a gender-bending art form by which individuals - including cis male, non-binary and transgender individuals - use clothing and makeup to exaggerate and replicate female features. -

Women's History Month

The Office of Senate President Karen E. Spilka Women’s History Month There are so many women who have shaped Massachusetts, here are 88 from past and present whose work, advocacy, and legacy live on. Zipporah Potter Atkins 1645-1705 An accurate Atkins was the first African-American landowner in Boston. illustration of Zipporah Potter Atkins does not exist. Weetamoo 1676 As Sachem of Wampanoags in Plymouth, she led forces to drive out European settlers, and was eventually killed by English colonists. Victims of the Salem Witch Trials and Sarah Clayes 1638-1703 Fourteen women were tried, sentenced, and executed in the Salem Witch Trials in 1692. They are: Bridget Bishop, Martha Carrier, Martha Corey, Mary Eastey, Sarah Good, Elizabeth Howe, Susannah Martin, Rebecca Nurse, Mary & Alice Parker, Ann Pudeator, Wilmot Redd, Margaret Scott, and Sarah Wildes. Sarah Clayes fled the Salem Witch Trials to establish a safe haven in Framingham for other accused women. Elizabeth Freeman 1742-1829 Also known as Mum Bett, she was the first enslaved woman to file and win a freedom suit in Massachusetts. The Massachsuetts Supreme Judicial Court ruling in Freeman’s favor found slavery to be unconstitu- tional, according to the 1780 Massachusetts State Constitution. Abigail Adams 1744-1818 Along with being the second First Lady of the United States, Adams was an abolitionist and advocate for women’s rights. She is from Weymouth and moved to Quincy, MA. Phillis Wheatley 1753-1784 Wheatley was an enslaved poet from Senegal or Gambia working in Boston who corresponded with George Washington. Deborah Sampson 1760-1827 Injured in battle in the Revolutionary War, and disguised as a man, she suffered injuries that she managed to heal herself so that doctors would not discover her gender.