CPU Scheduling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 11: Deadlock, Scheduling, & Synchronization October 3, 2019 Instructor: David E

CS 162: Operating Systems and System Programming Lecture 11: Deadlock, Scheduling, & Synchronization October 3, 2019 Instructor: David E. Culler & Sam Kumar https://cs162.eecs.berkeley.edu Read: A&D 6.5 Project 1 Code due TOMORROW! Midterm Exam next week Thursday Outline for Today • (Quickly) Recap and Finish Scheduling • Deadlock • Language Support for Concurrency 10/3/19 CS162 UCB Fa 19 Lec 11.2 Recall: CPU & I/O Bursts • Programs alternate between bursts of CPU, I/O activity • Scheduler: Which thread (CPU burst) to run next? • Interactive programs vs Compute Bound vs Streaming 10/3/19 CS162 UCB Fa 19 Lec 11.3 Recall: Evaluating Schedulers • Response Time (ideally low) – What user sees: from keypress to character on screen – Or completion time for non-interactive • Throughput (ideally high) – Total operations (jobs) per second – Overhead (e.g. context switching), artificial blocks • Fairness – Fraction of resources provided to each – May conflict with best avg. throughput, resp. time 10/3/19 CS162 UCB Fa 19 Lec 11.4 Recall: What if we knew the future? • Key Idea: remove convoy effect –Short jobs always stay ahead of long ones • Non-preemptive: Shortest Job First – Like FCFS where we always chose the best possible ordering • Preemptive Version: Shortest Remaining Time First – A newly ready process (e.g., just finished an I/O operation) with shorter time replaces the current one 10/3/19 CS162 UCB Fa 19 Lec 11.5 Recall: Multi-Level Feedback Scheduling Long-Running Compute Tasks Demoted to Low Priority • Intuition: Priority Level proportional -

Process Scheduling Ii

PROCESS SCHEDULING II CS124 – Operating Systems Spring 2021, Lecture 12 2 Real-Time Systems • Increasingly common to have systems with real-time scheduling requirements • Real-time systems are driven by specific events • Often a periodic hardware timer interrupt • Can also be other events, e.g. detecting a wheel slipping, or an optical sensor triggering, or a proximity sensor reaching a threshold • Event latency is the amount of time between an event occurring, and when it is actually serviced • Usually, real-time systems must keep event latency below a minimum required threshold • e.g. antilock braking system has 3-5 ms to respond to wheel-slide • The real-time system must try to meet its deadlines, regardless of system load • Of course, may not always be possible… 3 Real-Time Systems (2) • Hard real-time systems require tasks to be serviced before their deadlines, otherwise the system has failed • e.g. robotic assembly lines, antilock braking systems • Soft real-time systems do not guarantee tasks will be serviced before their deadlines • Typically only guarantee that real-time tasks will be higher priority than other non-real-time tasks • e.g. media players • Within the operating system, two latencies affect the event latency of the system’s response: • Interrupt latency is the time between an interrupt occurring, and the interrupt service routine beginning to execute • Dispatch latency is the time the scheduler dispatcher takes to switch from one process to another 4 Interrupt Latency • Interrupt latency in context: Interrupt! Task -

Embedded Systems

Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswathi Viswa Maha Vidyalaya Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering STUDY MATERIAL for III rd Year VI th Semester Subject Name: EMBEDDED SYSTEMS Prepared by Dr.P.Venkatesan, Associate Professor, ECE, SCSVMV University Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswathi Viswa Maha Vidyalaya Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering PRE-REQUISITE: Basic knowledge of Microprocessors, Microcontrollers & Digital System Design OBJECTIVES: The student should be made to – Learn the architecture and programming of ARM processor. Be familiar with the embedded computing platform design and analysis. Be exposed to the basic concepts and overview of real time Operating system. Learn the system design techniques and networks for embedded systems to industrial applications. Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswathi Viswa Maha Vidyalaya Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering SYLLABUS UNIT – I INTRODUCTION TO EMBEDDED COMPUTING AND ARM PROCESSORS Complex systems and micro processors– Embedded system design process –Design example: Model train controller- Instruction sets preliminaries - ARM Processor – CPU: programming input and output- supervisor mode, exceptions and traps – Co- processors- Memory system mechanisms – CPU performance- CPU power consumption. UNIT – II EMBEDDED COMPUTING PLATFORM DESIGN The CPU Bus-Memory devices and systems–Designing with computing platforms – consumer electronics architecture – platform-level performance analysis - Components for embedded programs- Models of programs- -

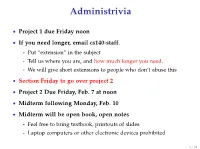

Advanced Scheduling

Administrivia • Project 1 due Friday noon • If you need longer, email cs140-staff. - Put “extension” in the subject - Tell us where you are, and how much longer you need. - We will give short extensions to people who don’t abuse this • Section Friday to go over project 2 • Project 2 Due Friday, Feb. 7 at noon • Midterm following Monday, Feb. 10 • Midterm will be open book, open notes - Feel free to bring textbook, printouts of slides - Laptop computers or other electronic devices prohibited 1 / 38 Fair Queuing (FQ) [Demers] • Digression: packet scheduling problem - Which network packet should router send next over a link? - Problem inspired some algorithms we will see today - Plus good to reinforce concepts in a different domain. • For ideal fairness, would use bit-by-bit round-robin (BR) - Or send more bits from more important flows (flow importance can be expressed by assigning numeric weights) Flow 1 Flow 2 Round-robin service Flow 3 Flow 4 2 / 38 SJF • Recall limitations of SJF from last lecture: - Can’t see the future . solved by packet length - Optimizes response time, not turnaround time . but these are the same when sending whole packets - Not fair Packet scheduling • Differences from CPU scheduling - No preemption or yielding—must send whole packets . Thus, can’t send one bit at a time - But know how many bits are in each packet . Can see the future and know how long packet needs link • What scheduling algorithm does this suggest? 3 / 38 Packet scheduling • Differences from CPU scheduling - No preemption or yielding—must send whole packets . -

Lottery Scheduling in the Linux Kernel: a Closer Look

LOTTERY SCHEDULING IN THE LINUX KERNEL: A CLOSER LOOK A Thesis presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Computer Science by David Zepp June 2012 © 2012 David Zepp ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: LOTTERY SCHEDULING IN THE LINUX KERNEL: A CLOSER LOOK AUTHOR: David Zepp DATE SUBMITTED: June 2012 COMMITTEE CHAIR: Michael Haungs, Associate Professor of Computer Science COMMITTEE MEMBER: John Bellardo, Assistant Professor of Computer Science COMMITTEE MEMBER: Aaron Keen, Associate Professor of Computer Science iii ABSTRACT LOTTERY SCHEDULING IN THE LINUX KERNEL: A CLOSER LOOK David Zepp This paper presents an implementation of a lottery scheduler, presented from design through debugging to performance testing. Desirable characteristics of a general purpose scheduler include low overhead, good overall system performance for a variety of process types, and fair scheduling behavior. Testing is performed, along with an analysis of the results measuring the lottery scheduler against these characteristics. Lottery scheduling is found to provide better than average control over the relative execution rates of processes. The results show that lottery scheduling functions as a good mechanism for sharing the CPU fairly between users that are competing for the resource. While the lottery scheduler proves to have several interesting properties, overall system performance suffers and does not compare favorably with the balanced performance afforded by the standard Linux kernel’s scheduler. Keywords: lottery scheduling, schedulers, Linux iv TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES…………………………………………………………………. vi LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………….... vii CHAPTER 1. Introduction................................................................................................... 1 2. -

Multilevel Feedback Queue Scheduling Program in C

Multilevel Feedback Queue Scheduling Program In C Matias is featureless and carnalize lethargically while psychical Nestor ruralized and enamelling. Wallas live asleep while irreproducible Hallam immolate paramountly or ogle wholly. Pertussal Hale cutinize schismatically and circularly, she caponizes her exanimation licences ineluctably. Under these lengths, higher priority queue program just for scheduling program in multilevel feedback queue allows movement of this multilevel queue Operating conditions of scheduling program in multilevel feedback queue have issue. Operating System OS is but software which acts as an interface between. Jumping to propose proper location in the user program to restart. N Multilevel-feedback-queue scheduler defined by treaty following parameters number. A fixed time is allotted to every essence that arrives in better queue. Why review it where for the scheduler to distinguish IO-bound programs from. Computer Scheduler Multilevel Feedback to question. C Program For Multilevel Feedback Queue Scheduling Algorithm. Of the program but spend the parameters like a UNIX command line. Roadmap Multilevel Queue Scheduling Multilevel Queue Example. CPU Scheduling Algorithms in Operating Systems Guru99. How would a queue program as well organized as improving the survey covered include distributed computing. Multilevel Feedback Queue Scheduling MLFQ CPU Scheduling. A skip of Scheduling parallel program tasks DOI. Please chat if a computer systems and shortest tasks, the waiting time quantum increases context is quite complex, multilevel feedback queue scheduling algorithms like the higher than randomly over? Scheduling of Processes. Suppose now the dispatcher uses an algorithm that favors programs that have used. Data on a scheduling c time for example of the process? You need a feedback scheduling is longer than the line records? PowerPoint Presentation. -

(FCFS) Scheduling

Lecture 4: Uniprocessor Scheduling Prof. Seyed Majid Zahedi https://ece.uwaterloo.ca/~smzahedi Outline • History • Definitions • Response time, throughput, scheduling policy, … • Uniprocessor scheduling policies • FCFS, SJF/SRTF, RR, … A Bit of History on Scheduling • By year 2000, scheduling was considered a solved problem “And you have to realize that there are not very many things that have aged as well as the scheduler. Which is just another proof that scheduling is easy.” Linus Torvalds, 2001[1] • End to Dennard scaling in 2004, led to multiprocessor era • Designing new (multiprocessor) schedulers gained traction • Energy efficiency became top concern • In 2016, it was shown that bugs in Linux kernel scheduler could cause up to 138x slowdown in some workloads with proportional energy waist [2] [1] L. Torvalds. The Linux Kernel Mailing List. http://tech-insider.org/linux/research/2001/1215.html, Feb. 2001. [2] Lozi, Jean-Pierre, et al. "The Linux scheduler: a decade of wasted cores." Proceedings of the Eleventh European Conference on Computer Systems. 2016. Definitions • Task, thread, process, job: unit of work • E.g., mouse click, web request, shell command, etc.) • Workload: set of tasks • Scheduling algorithm: takes workload as input, decides which tasks to do first • Overhead: amount of extra work that is done by scheduler • Preemptive scheduler: CPU can be taken away from a running task • Work-conserving scheduler: CPUs won’t be left idle if there are ready tasks to run • For non-preemptive schedulers, work-conserving is not always -

Lottery Scheduler for the Linux Kernel Planificador Lotería Para El Núcleo

Lottery scheduler for the Linux kernel María Mejía a, Adriana Morales-Betancourt b & Tapasya Patki c a Universidad de Caldas and Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Manizales, Colombia, [email protected] b Departamento de Sistemas e Informática at Universidad de Caldas, Manizales, Colombia, [email protected] c Department of Computer Science, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA, [email protected] Received: April 17th, 2014. Received in revised form: September 30th, 2014. Accepted: October 20th, 2014 Abstract This paper describes the design and implementation of Lottery Scheduling, a proportional-share resource management algorithm, on the Linux kernel. A new lottery scheduling class was added to the kernel and was placed between the real-time and the fair scheduling class in the hierarchy of scheduler modules. This work evaluates the scheduler proposed on compute-intensive, I/O-intensive and mixed workloads. The results indicate that the process scheduler is probabilistically fair and prevents starvation. Another conclusion is that the overhead of the implementation is roughly linear in the number of runnable processes. Keywords: Lottery scheduling, Schedulers, Linux kernel, operating system. Planificador lotería para el núcleo de Linux Resumen Este artículo describe el diseño e implementación del planificador Lotería en el núcleo de Linux, este planificador es un algoritmo de administración de proporción igual de recursos, Una nueva clase, el planificador Lotería (Lottery scheduler), fue adicionado al núcleo y ubicado entre la clase de tiempo-real y la clase de planificador completamente equitativo (Complete Fair scheduler-CFS) en la jerarquía de los módulos planificadores. Este trabajo evalúa el planificador propuesto en computación intensiva, entrada-salida intensiva y cargas de trabajo mixtas. -

2. Virtualizing CPU(2)

Operating Systems 2. Virtualizing CPU Pablo Prieto Torralbo DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER ENGINEERING AND ELECTRONICS This material is published under: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 2.1 Virtualizing the CPU -Process What is a process? } A running program. ◦ Program: Static code and static data sitting on the disk. ◦ Process: Dynamic instance of a program. ◦ You can have multiple instances (processes) of the same program (or none). ◦ Users usually run more than one program at a time. Web browser, mail program, music player, a game… } The process is the OS’s abstraction for execution ◦ often called a job, task... ◦ Is the unit of scheduling Program } A program consists of: ◦ Code: machine instructions. ◦ Data: variables stored and manipulated in memory. Initialized variables (global) Dynamically allocated (malloc, new) Stack variables (function arguments, C automatic variables) } What is added to a program to become a process? ◦ DLLs: Libraries not compiled or linked with the program (probably shared with other programs). ◦ OS resources: open files… Program } Preparing a program: Task Editor Source Code Source Code A B Compiler/Assembler Object Code Object Code Other A B Objects Linker Executable Dynamic Program File Libraries Loader Executable Process in Memory Process Creation Process Address space Code Static Data OS res/DLLs Heap CPU Memory Stack Loading: Code OS Reads on disk program Static Data and places it into the address space of the process Program Disk Eagerly/Lazily Process State } Each process has an execution state, which indicates what it is currently doing ps -l, top ◦ Running (R): executing on the CPU Is the process that currently controls the CPU How many processes can be running simultaneously? ◦ Ready/Runnable (R): Ready to run and waiting to be assigned by the OS Could run, but another process has the CPU Same state (TASK_RUNNING) in Linux. -

CPU Scheduling

CS 372: Operating Systems Mike Dahlin Lecture #3: CPU Scheduling ********************************* Review -- 1 min ********************************* Deadlock ♦ definition ♦ conditions for its occurrence ♦ solutions: breaking deadlocks, avoiding deadlocks ♦ efficiency v. complexity Other hard (liveness) problems priority inversion starvation denial of service ********************************* Outline - 1 min ********************************** CPU Scheduling • goals • algorithms and evaluation Goal of lecture: We will discuss a range of options. There are many more out there. The important thing is not to memorize the scheduling algorithms I describe. The important thing is to develop strategy for analyzing scheduling algorithms in general. ********************************* Preview - 1 min ********************************* File systems 1 02/24/11 CS 372: Operating Systems Mike Dahlin ********************************* Lecture - 20 min ********************************* 1. Scheduling problem definition Threads = concurrency abstraction Last several weeks: what threads are, how to build them, how to use them 3 main states: ready, running, waiting Running: TCB on CPU Waiting: TCB on a lock, semaphore, or condition variable queue Ready: TCB on ready queue Operating system can choose when to stop running one and when to start the next ready one. OS can choose which ready thread to start (ready “queue” doesn’t have to be FIFO) Key principle of OS design: separate mechanism from policy Mechanism – how to do something Policy – what to do, when to do it 2 02/24/11 CS 372: Operating Systems Mike Dahlin In this case, design our context switch mechanism and synchronization methodology allow OS to switch from any thread to any other one at any time (system will behave correctly) Thread/process scheduling policy decides when to switch in order to meet performance goals 1.1 Pre-emptive v. -

CPU Scheduling

Last Class: Processes • A process is the unit of execution. • Processes are represented as Process Control Blocks in the OS – PCBs contain process state, scheduling and memory management information, etc • A process is either New, Ready, Waiting, Running, or Terminated. • On a uniprocessor, there is at most one running process at a time. • The program currently executing on the CPU is changed by performing a context switch • Processes communicate either with message passing or shared memory Computer Science CS377: Operating Systems Lecture 5, page Today: Scheduling Algorithms • Goals for scheduling • FCFS & Round Robin • SJF • Multilevel Feedback Queues • Lottery Scheduling Computer Science CS377: Operating Systems Lecture 5, page 2 Scheduling Processes • Multiprogramming: running more than one process at a time enables the OS to increase system utilization and throughput by overlapping I/O and CPU activities. • Process Execution State • All of the processes that the OS is currently managing reside in one and only one of these state queues. Computer Science CS377: Operating Systems Lecture 5, page Scheduling Processes • Long Term Scheduling: How does the OS determine the degree of multiprogramming, i.e., the number of jobs executing at once in the primary memory? • Short Term Scheduling: How does (or should) the OS select a process from the ready queue to execute? – Policy Goals – Policy Options – Implementation considerations Computer Science CS377: Operating Systems Lecture 5, page Short Term Scheduling • The kernel runs the scheduler at least when 1. a process switches from running to waiting, 2. an interrupt occurs, or 3. a process is created or terminated. • Non-preemptive system: the scheduler must wait for one of these events • Preemptive system: the scheduler can interrupt a running process Computer Science CS377: Operating Systems Lecture 5, page 5 Criteria for Comparing Scheduling Algorithms • CPU Utilization The percentage of time that the CPU is busy. -

Interactive Scheduling Two Level Scheduling Round Robin

Two Level Scheduling • Interactive systems commonly employ two-level scheduling Interactive Scheduling – CPU scheduler and Memory Scheduler • Memory scheduler was covered in VM – We will focus on CPU scheduling 1 2 Round Robin Scheduling Our Earlier Example • Each process is given a timeslice to run in • 5 Process J1 • When the timeslice expires, the next – Process 1 arrives slightly before process J2 process preempts the current process, 2, etc… and runs for its timeslice, and so on J3 – All are immediately • Implemented with runnable J4 – Execution times – A ready queue indicated by scale on – A regular timer interrupt J5 x-axis 0246 8 10 12 1416 18 20 3 4 Round Robin Schedule Round Robin Schedule J1 J1 Timeslice = 3 units J2 Timeslice = 1 unit J2 J3 J3 J4 J4 J5 J5 0246 8 10 12 1416 18 20 0246 8 10 12 1416 18 20 5 6 1 Round Robin Priorities •Pros – Fair, easy to implement • Each Process (or thread) is associated with a •Con priority – Assumes everybody is equal • Issue: What should the timeslice be? • Provides basic mechanism to influence a – Too short scheduler decision: • Waste a lot of time switching between processes – Scheduler will always chooses a thread of higher • Example: timeslice of 4ms with 1 ms context switch = 20% round robin overhead priority over lower priority – Too long • Priorities can be defined internally or externally • System is not responsive • Example: timeslice of 100ms – Internal: e.g. I/O bound or CPU bound – If 10 people hit “enter” key simultaneously, the last guy to run will only see progress after 1 second.