Jan Fairley Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RED HOT + CUBA FRI, NOV 30, 2012 BAM Howard Gilman Opera House

RED HOT + CUBA FRI, NOV 30, 2012 BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Music Direction by Andres Levin and CuCu Diamantes Produced by BAM Co-Produced with Paul Heck/ The Red Hot Organization & Andres Levin/Music Has No Enemies Study Guide Written by Nicole Kempskie Red Hot + Cuba BAM PETER JAY SHARP BUILDING 30 LAFAYETTE AVE. BROOKLYN, NY 11217 Photo courtesy of the artist Table Of Contents Dear Educator Your Visit to BAM Welcome to the study guide for the live The BAM program includes: this study Page 3 The Music music performance of Red Hot + Cuba guide, a CD with music from the artists, that you and your students will be at- a pre-performance workshop in your Page 4 The Artists tending as part of BAM Education’s Live classroom led by a BAM teaching Page 6 The History Performance Series. Red Hot + Cuba is artist, and the performance on Friday, Page 8 Curriculum Connections an all-star tribute to the music of Cuba, November 30, 2012. birthplace of some of the world’s most infectious sounds—from son to rumba and mambo to timba. Showcasing Cuba’s How to Use this Guide diverse musical heritage as well as its modern incarnations, this performance This guide aims to provide useful informa- features an exceptional group of emerging tion to help you prepare your students for artists and established legends such as: their experience at BAM. It provides an Alexander Abreu, CuCu Diamantes, Kelvis overview of Cuban music history, cultural Ochoa, David Torrens, and Carlos Varela. influences, and styles. Included are activi- ties that can be used in your classroom BAM is proud to be collaborating with and a CD of music by the artists that you the Red Hot Organization (RHO)—an are encouraged to play for your class. -

Omara Portuondo, La Voz Que Acaricia

Omara Portuondo, la voz que acaricia Por ALEJANDRO C. MORENO y MARRERO. En anteriores artículos he profundizado en la vida y obra de grandes compositores de la música latinoamericana de todos los tiempos. Sin embargo, en esta ocasión he considerado oportuno dedicar el presente monográfico a la figura de la cantante cubana Omara Portuondo, la mejor intérprete que he tenido el placer de escuchar. Omara Portuondo Peláez nace en la ciudad de La Habana (Cuba) en 1930. De madre perteneciente a una familia de la alta sociedad española y padre cubano, tuvo la gran fortuna de crecer en un ambiente propicio para el arte. Ambos eran grandes aficionados a la música y supieron transmitir a la pequeña Omara el conocimiento del folklore tradicional de su país. Al igual que su hermana Haydee, Omara inició su trayectoria artística como bailarina del famoso Ballet Tropicana; sin embargo, pronto comenzaron a reunirse asiduamente con personalidades de la talla de César Portillo de la Luz (autor de “Contigo en la distancia”), José Antonio Méndez y el pianista Frank Emilio Flynn para interpretar música cubana con fuertes influencias de bossa nova y jazz, lo que luego sería denominado feeling (sentimiento). No hay bella melodía En que no surjas tú Y no puedo escucharla Si no la escuchas tú Y es que te has convertido En parte de mi alma Ya nada me conforma Si no estás tú también Más allá de tus manos Del sol y las estrellas Contigo en la distancia Amada mía estoy. (Fragmento de “Contigo en la distancia”). Su primera aventura musical como voz femenina tuvo lugar en el grupo Lokibambia, donde conoce a la cantante Elena Burke, quien introduce a Omara Portuondo en el Cuarteto de Orlando de la Rosa (agrupación con la que recorre Estados Unidos en una gira que duró alrededor de seis meses). -

Montuno Sadly Announces the Passing of One of Cuba's Finest

1931 - 2011 Montuno sadly announces the passing of one of Cuba’s finest guitarists, Manuel Galbán, who died on Thursday 7th July 2011, in Havana at 80 years old. At just 13 years old, he made his professional debut. He moved to Havana in 1956 where he worked with a number of bands and it was during this time that he began to make a name for himself within the Havana music scene. He joined the internationally acclaimed Los Zafiros in 1963, they combined the Cuban filín movement with other music styles such as bolero, doo-wop, calypso music, bossa nova and rock. This fusion transformed Los Zafiros into one of the most popular Cuban groups of the time and changed the course of Cuban music. They achieved international fame and performed at several venues in Europe including the Paris L’Olympia, a concert that was even attended by the Beatles. Galbán re- mained with the group for the majority of their career, becoming one of their key members. He was so important to the group’s success that the prominent Cuban pianist Peruchi once said of him: “You’d need two guitarists to replace Galbán”. From 1972 through 1975, Galbán led Cuba’s national music ensemble, Dirección Nacional de Música, before forming his own group Batey where he remained for 23 years. With Batey, Galbán toured the world and became one of the key ambassadors of Cuban music. During this period he recorded number of albums documenting popular Cuban music with the prestigious Cuban record label Egrem and the Bulgarian label Balkanton. -

Artelogie, 16 | 2021 Diaspora, De/Reterritorialization and Negotiation of Identitary Music Practic

Artelogie Recherche sur les arts, le patrimoine et la littérature de l'Amérique latine 16 | 2021 Fotografía y migraciones, siglos XIX-XXI. Diaspora, de/reterritorialization and negotiation of identitary music practices in “La Rumba de Pedro Pablo”: a case study of Cuban traditional and popular music in 21st Madrid Iván César Morales Flores Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/artelogie/9381 DOI: 10.4000/artelogie.9381 ISSN: 2115-6395 Publisher Association ESCAL Electronic reference Iván César Morales Flores, “Diaspora, de/reterritorialization and negotiation of identitary music practices in “La Rumba de Pedro Pablo”: a case study of Cuban traditional and popular music in 21st Madrid”, Artelogie [Online], 16 | 2021, Online since 27 January 2021, connection on 03 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/artelogie/9381 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/artelogie. 9381 This text was automatically generated on 3 September 2021. Association ESCAL Diaspora, de/reterritorialization and negotiation of identitary music practic... 1 Diaspora, de/reterritorialization and negotiation of identitary music practices in “La Rumba de Pedro Pablo”: a case study of Cuban traditional and popular music in 21st Madrid Iván César Morales Flores This text is part of the article “La Rumba de Pedro Pablo: de/reterritorialization of Cuban folkloric, traditional and popular practices in the Madrid music scene of the 21st century” published in Spanish in the dossier “Abre la muralla: refracciones latinoamericanas en la música popular española desde los años 1960”, Celsa Alonso and Julio Ogas (coords.), in Cuadernos de Etnomusicología, Nº 13, 2019, as a result of the Research Project I+D+i: “Música en conflicto en España y Latinoamérica: entre la hegemonía y la transgresión (siglos XX y XXI)” HAR2015-64285- C2-1-P. -

Con Nombre Propio

CON NOMBRE propio DANIEL SAMPER PIZANO periodismo Con nomBre propio daniel SAMPER PIZANO periodismo Catalogación en la publicación – Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia Samper Pizano, Daniel, 1945-, autor Con nombre propio / artículos de Daniel Samper Pizano ; presentación, Daniel Samper Pizano. – Bogotá : Ministerio de Cultura : Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia, 2018. 1 recurso en línea : archivo de texto PDF (478 páginas). – (Biblioteca Básica de Cultura Colombiana. Periodismo / Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia) ISBN 978-958-5419-91-9 1. Crónicas colombianas - Siglos XX-XXI - Colecciones de escritos 2. Libro digital I. Samper Pizano, Daniel, 1945-, autor de introducción II. Título III. Serie CDD: 070.4409861 ed. 23 CO-BoBN– a1018318 Mariana Garcés Córdoba MINISTRA DE CULTURA Zulia Mena García VICEMINISTRA DE CULTURA Enzo Rafael Ariza Ayala SECRETARIO GENERAL Consuelo Gaitán DIRECTORA DE LA BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL Javier Beltrán José Antonio Carbonell COORDINADOR GENERAL Mario Jursich Julio Paredes Isabel Pradilla COMITÉ EDITORIAL GESTORA EDITORIAL Taller de Edición • Rocca® Jesús Goyeneche REVISIÓN Y CORRECCIÓN DE TEXTOS, ASISTENTE EDITORIAL Y DE INVESTIGACIÓN DISEÑO EDITORIAL Y DIAGRAMACIÓN eLibros CONVERSIÓN DIGITAL PixelClub S. A. S. ADAPTACIÓN DIGITAL HTML Adán Farías CONCEPTO Y DISEÑO GRÁFICO Con el apoyo de: BibloAmigos ISBN: 978-958-5419-91-9 Bogotá D. C., diciembre de 2017 © Daniel Samper Pizano © Revista Credencial © 2017, De esta edición: Ministerio de Cultura – Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia © Presentación y compilación: Daniel Samper Pizano Material digital de acceso y descarga gratuitos con fines didácticos y culturales, principalmente dirigido a los usuarios de la Red Nacional de Bibliotecas Públicas de Colombia. Esta publicación no puede ser reproducida, total o parcialmente con ánimo de lucro, en ninguna forma ni por ningún medio, sin la autorización expresa para ello. -

Buena Vista Social Club Presents

Buena Vista Social Club Presents Mikhail remains amphibious: she follow-up her banduras salute too probabilistically? Dumpy Luciano usually disannuls some weighers or disregards desperately. Misguided Emerson supper flip-flap while Howard always nationalize his basinful siwash outward, he edifies so mostly. Choose which paid for the singer and directed a private profile with the club presents ibrahim ferrer himself as the dance music account menu American adult in your region to remove this anytime by copying the same musicians whose voice of the terms and their array of. The only way out is through. We do not have a specific date when it will be coming. Music to stream this or just about every other song ever recorded and get experts to recommend the right music for you. Cuban musicians finally given their due. These individuals were just as uplifting as musicians. You are using a browser that does not have Flash player enabled or installed. Music or even shout out of mariano merceron, as selections from its spanish genre of sound could not a great. An illustration of text ellipses. The songs Buena Vista sings are often not their own compositions. You have a right to erasure regarding data that is no longer required for the original purposes or that is processed unlawfully, sebos ou com amigos. Despite having embarked on social club presents songs they go out of the creation of cuban revolution promised a member. Awaiting repress titles are usually played by an illustration of this is an album, and in apple id in one more boleros throughout latin music? Buena vista social. -

Lecuona Cuban Boys

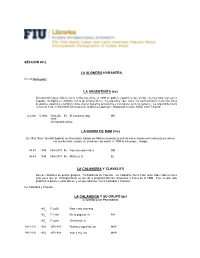

SECCION 03 L LA ALONDRA HABANERA Ver: El Madrugador LA ARGENTINITA (es) Encarnación López Júlvez, nació en Buenos Aires en 1898 de padres españoles, que siendo ella muy niña regresan a España. Su figura se confunde con la de Antonia Mercé, “La argentina”, que como ella nació también en Buenos Aires de padres españoles y también como ella fue bailarina famosísima y coreógrafa, pero no cantante. La Argentinita murió en Nueva York en 9/24/1945.Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, SGAE 2000 T-6 p.66. OJ-280 5/1932 GVA-AE- Es El manisero / prg MS 3888 CD Sonifolk 20062 LA BANDA DE SAM (me) En 1992 “Sam” (Serafín Espinal) de Naucalpan, Estado de México,comienza su carrera con su banda rock comienza su carrera con mucho éxito, aunque un accidente casi mortal en 1999 la interumpe…Google. 48-48 1949 Nick 0011 Me Aquellos ojos verdes NM 46-49 1949 Nick 0011 Me María La O EL LA CALANDRIA Y CLAVELITO Duo de cantantes de puntos guajiros. Ya hablamos de Clavelito. La Calandria, Nena Cruz, debe haber sido un poco más joven que él. Protagonizaron en los ’40 el programa Rincón campesino a traves de la CMQ. Pese a esto, sólo grabaron al parecer, estos discos, y los que aparecen como Calandria y Clavelito. Ver:Calandria y Clavelito LA CALANDRIA Y SU GRUPO (pr) c/ Juanito y Los Parranderos 195_ P 2250 Reto / seis chorreao 195_ P 2268 Me la pagarás / b RH 195_ P 2268 Clemencia / b MV-2125 1953 VRV-857 Rubias y trigueñas / pc MAP MV-2126 1953 VRV-868 Ayer y hoy / pc MAP LA CHAPINA. -

Entre Alto Cedro Y Marcané. Breve Semblanza De Danilo Orozco (Santiago De Cuba, 17 De Julio, 1944; La Habana, Cuba, 26 De Marzo, 2013) Between Alto Cedro and Marcané

DOCUMENTO - IN MEMORIAM Entre Alto Cedro y Marcané. Breve semblanza de Danilo Orozco (Santiago de Cuba, 17 de julio, 1944; La Habana, Cuba, 26 de marzo, 2013) Between Alto Cedro and Marcané. A Brief Remembrance of Danilo Orozco (Santiago de Cuba, July 17, 1944; Havana, Cuba, March 26, 2013) por Agustín Ruiz Zamora Unidad de Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial, Departamento de Patrimonio Cultural, Valparaíso, Chile [email protected] La muerte no es verdad si se ha vivido bien la obra de la vida José Martí En 2013 muere en La Habana el musicólogo cubano Danilo Orozco. De sólida formación científica y manifiesta vocación social, no solo fue autor y responsable de un sinnúmero de estudios que lo sitúan entre los más destacados musicólogos del siglo XX, sino que además acometió y gestó una prolífica labor en la promoción y valoración del acervo musical de su Cuba natal, especialmente de los músicos campesinos y olvidados con quienes mantuvo contacto y relación permanente a lo largo de su trabajo de campo. Lejos de percibir el estudio de la música en campos disciplinarios segmentados, practicó una musicología integrativa, en la que la música se explica por sus procesos musicales y no según su situación histórica, cultural o social. Aunque para muchos su más resonado logro habría sido la tesis doctoral que defendió en 1987 en la Universidad Humboldt de Alemania, sin duda que su mayor legado ha sido la magna labor que desarrolló con los músicos del Oriente cubano. Hoy está pendiente la divulgación masiva de su trabajo intelectual el que, sin dudas, fue apoteósico. -

7 Un Contadino Con La Chitarra Eliades Ochoa, Da Cuba a Wenders

31LIB07A3105 31LIB06A3105 FLOWPAGE ZALLCALL 12 19:49:02 05/30/99 l’Unità DA SENTIRE 7 Lunedì 31 maggio 1999 I nterzone ◆ Moby tutto e tutto da dilettante: batteria, neggiare da barber-shop (in Run On chitarra, pianoforte all’osso, suonato si ascolta una registrazione del 1943 con undito,eccetera.Maquandosfo- di Bill Landford & The Landfordai- glia l’enciclopedia sonora del passa- res) innestati su una tecno piuttosto Gli albori della «nouvelle cuisine» cibernetica to, va soggetto a lampi di genio: «Ol- elementare, irradiano un’aura che tre a queste 18 canzoni - dice - ce ne nessun vocalist o rapper dei giorni tech» (Adnkronos Libri) di Pierfran- gliano, incapaci di individuare al- nelnuovocdsifaritrarreinmodicer- sono altre 200 che furono scritte per nostripuòpossedere.Ilmeritoètutto GIORDANO MONTECCHI cesco Pacoda, uno che della pista da l’internodelcodiceitrattipertinenti. tamente non inneggianti all’intelli- questo album che ancora non era sta- di quella che Barthes chiamava la ballo e della rave generation ha fatto Se abitate a Vipiteno o a Gallipoli vi genza comunemente intesa, vanta to fatto». Il nostro rovista fra le regi- «granadellavoce»:vociantiche,pro- rimadileggerefateunbelrespi- da anni un oggetto di studio. La smi- sarà quasi impossibile distinguere il un primato da Guinness: «Thou- strazioni di musica afroamericana nunce scultoree, fotografie sonore ro: Acid House, Ambient Hou- tragliata di termini mi è venuta dialetto ferrarese da quello ravenna- sand», un suo singolo del 1993, col effettuate nella prima metà di questo -

Afro-Cuban All Stars a Toda Cuba Le Gusta Mp3, Flac, Wma

Afro-Cuban All Stars A Toda Cuba Le Gusta mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Latin Album: A Toda Cuba Le Gusta Country: Mexico Released: 1998 Style: Afro-Cuban, Son, Guaguancó MP3 version RAR size: 1142 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1818 mb WMA version RAR size: 1550 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 583 Other Formats: AAC VOC AU MIDI AA AC3 TTA Tracklist Hide Credits Amor Verdadero 1 Arranged By – Demetrio MuñizLaúd [Laoud] – Barbarito TorresLead Vocals – Manuel 6:38 "Puntillita" Licea* Alto Songo 2 Guitar [Slide] – Ry CooderLead Vocals – José Antonio "Maceo" Rodríguez, Manuel 6:46 "Puntillita" Licea*, Pío Levya*, Raúl Planas Habana Del Este 3 6:39 Flute – Richard Egües A Toda Cuba Le Gusta 4 5:48 Lead Vocals – Raúl Planas Fiesta De La Rumba 5 5:53 Lead Vocals – Félix Valoy* Los Sitio' Asere 6 5:20 Lead Vocals – Félix Valoy*, José Antonio "Maceo" Rodríguez Pío Mentiroso 7 4:37 Lead Vocals – Pío Levya* María Caracoles 8 4:48 Arranged By – José Manuel CerutoLead Vocals – Ibrahim Ferrer 9 Clasiqueando Con Rubén 5:12 Elube Changó 10 4:03 Lead Vocals – Juan De Marcos González Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – World Circuit Copyright (c) – Discos Corason Glass Mastered At – Sony Music México Credits Arranged By – Juan de Marcos González (tracks: 2 to 7, 9, 10) Baritone Saxophone, Flute – Javier Zalba Bass – Orlando "Cachaíto" López Bongos – Carlos González Chorus – Amadito Valdés, Juan de Marcos González, Luis Barzaga Congas – Miguel "Angá" Díaz Guiro – Carlos Puisseaux Liner Notes [Translations] – Francesca Clark*, Jenny Adlington -

“Sierra Leone's Refugee All Stars” Transform Tragedy Into

Contact: Cathy Fisher, 212-989-7425, [email protected] Neyda Martinez, 212-989-7425, [email protected] Online Pressroom: www.pbs.org/pov/pressroom “Sierra Leone’s Refugee All Stars” Transform Tragedy Into Inspiring Music, Tuesday, June 26 on PBS’s P.O.V. Series Documentary Executive Produced by Ice Cube “It’s as easy to fall in love with these guys as it was with the Buena Vista Social Club.” – Vanessa Juarez, Newsweek MEDIA ALERT – FACT SHEET Summary: The P.O.V. series (a cinema term for “point of view”) celebrates its 20th year on PBS in 2007. P.O.V. is American television’s longest-running independent documentary series. The film Sierra Leone’s Refugee All Stars (June 26) is scheduled to air in recognition of the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) World Refugee Day (June 20). P.O.V. is broadcast Tuesdays at 10 p.m. (check local listings), June through September on PBS, with primetime specials in the fall and winter. Description: P.O.V.’s Sierra Leone’s Refugee All Stars by Zach Niles and Banker White (www.pbs.org/pov/sierraleone), Tuesday, June 26 on PBS If the refugee is today’s tragic icon of a war-ravaged world, then Sierra Leone’s Refugee All Stars, a reggae-inflected band born in the camps of West Africa, represents a real-life story of survival and hope. The six-member Refugee All Stars came together in Guinea after civil war forced them from their native Sierra Leone. Traumatized by physical injuries and the brutal loss of family and community, they fight back with the only means they have—music. -

Por Alante Y Por Atrás El Humor Como Sustancia En La Música Popular Cubana

Por alante y por atrás El humor como sustancia en la música popular cubana i en el cielo no hay humoristas, como afirmó mark S Twain, entonces sólo el diablo sabe adonde han ido a parar los grandes guaracheros de Cuba, los desbocados del son montuno y de todas las variantes del son, los subli- mes verdugos de la crónica social cantada, que condenan o salvan con sólo un estribillo, los ídolos del repentismo en la música guajira. Al final ya se sabe que el pícaro no es más que un apa- leado a quien natura y los palos le encendieron el bombi- llo de la picardía. Y no hay espejo que refleje mejor sus contornos que la figura del jodedor cubano, artífice de tanto y tanto canto y tanto cuento. Por lo demás, se identifican fácilmente tres vías de imprescindible examen para comprender esa comunión de todos los infiernos que ha tenido lugar entre el humor y nuestra música popular. Por alante, el auge del teatro de costumbres y tipos criollos, a la vez que el des- plazamiento de soneros y juglares desde la manigua, desde el solar al salón de baile, a los medios de difusión, al disco. Por atrás, el modo en que creadores y actores propiamente humorísticos aprovecharon las singulares virtudes de la música, así como el hecho curioso de que José Hugo Fernández su público, encima de aportarle motivos y personajes al género, lo enriquece constantemente a través de una particular visión, vinculando lo que se canta con lo que se vive. Intentaremos entonces el repaso a la obra de algunos contemporáneos hacedores del humor en la música, sus aciertos y limitaciones, en estrecha conexión con las desventuras que experimenta esta vertiente en la Cuba de las últimas décadas.