Artelogie, 16 | 2021 Diaspora, De/Reterritorialization and Negotiation of Identitary Music Practic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Salsa Bass the Cuban Timba Revolution

BEYOND SALSA BASS THE CUBAN TIMBA REVOLUTION VOLUME 1 • FOR BEGINNERS FROM CHANGÜÍ TO SON MONTUNO KEVIN MOORE audio and video companion products: www.beyondsalsa.info cover photo: Jiovanni Cofiño’s bass – 2013 – photo by Tom Ehrlich REVISION 1.0 ©2013 BY KEVIN MOORE SANTA CRUZ, CA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without written permission of the author. ISBN‐10: 1482729369 ISBN‐13/EAN‐13: 978‐148279368 H www.beyondsalsa.info H H www.timba.com/users/7H H [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Introduction to the Beyond Salsa Bass Series...................................................................................... 11 Corresponding Bass Tumbaos for Beyond Salsa Piano .................................................................... 12 Introduction to Volume 1..................................................................................................................... 13 What is a bass tumbao? ................................................................................................................... 13 Sidebar: Tumbao Length .................................................................................................................... 1 Difficulty Levels ................................................................................................................................ 14 Fingering.......................................................................................................................................... -

¡Esto Parece Cuba!” Prácticas Musicales Y Cubanía En La Diáspora Cubana De Barcelona

Universitat de Barcelona Facultat de Geografia i Història Departament d’Antropologia Social i d’Història d’Amèrica i d’Àfrica Programa de Doctorat en Antropologia Social i Cultural Bienni 2003-2005 “¡Esto parece Cuba!” Prácticas musicales y cubanía en la diáspora cubana de Barcelona TESI DOCTORAL PRESENTADA PER IÑIGO SÁNCHEZ FUARROS codirigida pels Drs. Josep MARTÍ i PÉREZ i Gemma OROBITG CANAL Barcelona, 2008 A la memoria de mi padre, que se nos fue demasiado pronto. El exilio no es cosa del tiempo sino de espacios –por fundar, por huir, por conquistar- que cancelan la cronología de nuestras vidas. Iván de la Nuez, La balsa perpetua The exile knows his place, and that place is the imagination. Ricardo Pau-Llosa Imagination is not a place . You can´t live there, you can’t buy a house there, you can’t raise your children there. Gustavo Pérez-Firmat , Life on the Hyphen Tabla de contenidos Lista de ilustraciones 12 Prefacio 13 PARTE I – INTRODUCCIÓN 23 1. PRÓLOGO : LA MERCÉ CUBANA 25 2. LA DIÁSPORA CUBANA EN ESPAÑA 29 2.1 Generaciones diaspóricas 33 2.2 ¿Comunidad cubana en Barcelona? 46 3. PRÁCTICAS MUSICALES Y CUBANOS EN BARCELONA 54 3.1 Música, comunidad y cubaneo 54 3.2 Imaginarios musicales de lo cubano 58 3.3 La escena musical cubana en Barcelona 67 4. METODOLOGÍA 75 4.1 Las ciencias sociales y la diáspora cubana en España 77 4.2 La delimitación del obJeto de análisis 82 4.3 Los espacios de ocio como obJeto de análisis 90 4.4 Observador y participante 100 PARTE II – LAS RUTAS SOCIALES DEL CUBANEO 110 1. -

RED HOT + CUBA FRI, NOV 30, 2012 BAM Howard Gilman Opera House

RED HOT + CUBA FRI, NOV 30, 2012 BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Music Direction by Andres Levin and CuCu Diamantes Produced by BAM Co-Produced with Paul Heck/ The Red Hot Organization & Andres Levin/Music Has No Enemies Study Guide Written by Nicole Kempskie Red Hot + Cuba BAM PETER JAY SHARP BUILDING 30 LAFAYETTE AVE. BROOKLYN, NY 11217 Photo courtesy of the artist Table Of Contents Dear Educator Your Visit to BAM Welcome to the study guide for the live The BAM program includes: this study Page 3 The Music music performance of Red Hot + Cuba guide, a CD with music from the artists, that you and your students will be at- a pre-performance workshop in your Page 4 The Artists tending as part of BAM Education’s Live classroom led by a BAM teaching Page 6 The History Performance Series. Red Hot + Cuba is artist, and the performance on Friday, Page 8 Curriculum Connections an all-star tribute to the music of Cuba, November 30, 2012. birthplace of some of the world’s most infectious sounds—from son to rumba and mambo to timba. Showcasing Cuba’s How to Use this Guide diverse musical heritage as well as its modern incarnations, this performance This guide aims to provide useful informa- features an exceptional group of emerging tion to help you prepare your students for artists and established legends such as: their experience at BAM. It provides an Alexander Abreu, CuCu Diamantes, Kelvis overview of Cuban music history, cultural Ochoa, David Torrens, and Carlos Varela. influences, and styles. Included are activi- ties that can be used in your classroom BAM is proud to be collaborating with and a CD of music by the artists that you the Red Hot Organization (RHO)—an are encouraged to play for your class. -

Redalyc.Mambo on 2: the Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Hutchinson, Sydney Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City Centro Journal, vol. XVI, núm. 2, fall, 2004, pp. 108-137 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37716209 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 108 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City SYDNEY HUTCHINSON ABSTRACT As Nuyorican musicians were laboring to develop the unique sounds of New York mambo and salsa, Nuyorican dancers were working just as hard to create a new form of dance. This dance, now known as “on 2” mambo, or salsa, for its relationship to the clave, is the first uniquely North American form of vernacular Latino dance on the East Coast. This paper traces the New York mambo’s develop- ment from its beginnings at the Palladium Ballroom through the salsa and hustle years and up to the present time. The current period is characterized by increasing growth, commercialization, codification, and a blending with other modern, urban dance genres such as hip-hop. [Key words: salsa, mambo, hustle, New York, Palladium, music, dance] [ 109 ] Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 110 While stepping on count one, two, or three may seem at first glance to be an unimportant detail, to New York dancers it makes a world of difference. -

Groove in Cuban Dance Music: an Analysis of Son and Salsa Thesis

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Groove in Cuban Dance Music: An Analysis of Son and Salsa Thesis How to cite: Poole, Adrian Ian (2013). Groove in Cuban Dance Music: An Analysis of Son and Salsa. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2013 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000ef02 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk \ 1f'1f r ' \ I \' '. \ Groove in Cuban Dance Music: An Analysis of Son and Salsa Adrian Ian Poole esc MA Department of Music The Open University Submitted for examination towards the award of Doctor of Philosophy on 3 September 2012 Dntc \.?~ ,Sllbm.~'·\\(~·' I ~-'-(F~\:ln'lbCt i( I) D Qt C 0'1 f\;V·J 0 1('\: 7 M (~) 2 013 f1I~ w -;:~ ~ - 4 JUN 2013 ~ Q.. (:. The Library \ 7<{)0. en ~e'1l poo DONATION CO)"l.SlALt CAhon C()F) Iiiiii , III Groove in Cuban Dance Music: An Analysis of Son and Salsa Abstract The rhythmic feel or 'groove' of Cuban dance music is typically characterised by a dynamic rhythmic energy, drive and sense of forward motion that, for those attuned, has the ability to produce heightened emotional responses and evoke engagement and participation through physical movement and dance. -

Tenth Conference on Cuban and Cuban-American Studies

Cuban Research Institute School of International and Public Affairs Tenth Conference on Cuban and Cuban-American Studies “More Than White, More Than Mulatto, More Than Black”: Racial Politics in Cuba and the Americas “Más que blanco, más que mulato, más que negro”: La política racial en Cuba y las Américas Dedicated to Carmelo Mesa-Lago February 26-28, 2015 WELCOMING REMARKS I’m thrilled to welcome you to our Tenth Conference on Cuban and Cuban-American Studies. On Friday evening, we’ll sponsor the premiere of the PBS documentary Cuba: The Forgotten Organized by the Cuban Research Institute (CRI) of Florida International University (FIU) Revolution, directed by Glenn Gebhard. The film focuses on the role of the slain leaders since 1997, this biennial meeting has become the largest international gathering of scholars José Antonio Echeverría and Frank País in the urban insurrection movement against the specializing in Cuba and its diaspora. Batista government in Cuba during the 1950s. After the screening, Lillian Guerra will lead the discussion with the director; Lucy Echeverría, José Antonio’s sister; Agustín País, Frank’s As the program for our conference shows, the academic study of Cuba and its diaspora brother; and José Álvarez, author of a book about Frank País. continues to draw substantial interest in many disciplines of the social sciences and the humanities, particularly in literary criticism, history, anthropology, sociology, music, and the On Saturday, the last day of the conference, we’ll have a numerous and varied group of arts. We expect more than 250 participants from universities throughout the United States and presentations. -

Beyond Salsa for Ensemble a Guide to the Modern Cuban Rhythm Section

BEYOND SALSA FOR ENSEMBLE A GUIDE TO THE MODERN CUBAN RHYTHM SECTION PIANO • BASS • CONGAS • BONGÓ • TIMBALES • DRUMS VOLUME 1 • EFECTOS KEVIN MOORE REVISION 1.0 ©2012 BY KEVIN MOORE SANTA CRUZ, CA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without written permission of the author. ISBN‐10: 146817486X ISBN‐13/EAN‐13: 978‐1468174861 www.timba.com/ensemble www.timba.com/piano www.timba.com/clave www.timba.com/audio www.timba.com/percussion www.timba.com/users/7 [email protected] cover design: Kris Förster based on photos by: Tom Ehrlich photo subjects (clockwise, starting with drummer): Bombón Reyes, Daymar Guerra, Miguelito Escuriola, Pupy Pedroso, Francisco Oropesa, Duniesky Baretto Table of Contents Introduction to the Beyond Salsa Series .............................................................................................. 12 Beyond Salsa: The Central Premise .................................................................................................. 12 How the Series is Organized and Sold .......................................................................................... 12 Book ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Audio ....................................................................................................................................... -

Omara Portuondo, La Voz Que Acaricia

Omara Portuondo, la voz que acaricia Por ALEJANDRO C. MORENO y MARRERO. En anteriores artículos he profundizado en la vida y obra de grandes compositores de la música latinoamericana de todos los tiempos. Sin embargo, en esta ocasión he considerado oportuno dedicar el presente monográfico a la figura de la cantante cubana Omara Portuondo, la mejor intérprete que he tenido el placer de escuchar. Omara Portuondo Peláez nace en la ciudad de La Habana (Cuba) en 1930. De madre perteneciente a una familia de la alta sociedad española y padre cubano, tuvo la gran fortuna de crecer en un ambiente propicio para el arte. Ambos eran grandes aficionados a la música y supieron transmitir a la pequeña Omara el conocimiento del folklore tradicional de su país. Al igual que su hermana Haydee, Omara inició su trayectoria artística como bailarina del famoso Ballet Tropicana; sin embargo, pronto comenzaron a reunirse asiduamente con personalidades de la talla de César Portillo de la Luz (autor de “Contigo en la distancia”), José Antonio Méndez y el pianista Frank Emilio Flynn para interpretar música cubana con fuertes influencias de bossa nova y jazz, lo que luego sería denominado feeling (sentimiento). No hay bella melodía En que no surjas tú Y no puedo escucharla Si no la escuchas tú Y es que te has convertido En parte de mi alma Ya nada me conforma Si no estás tú también Más allá de tus manos Del sol y las estrellas Contigo en la distancia Amada mía estoy. (Fragmento de “Contigo en la distancia”). Su primera aventura musical como voz femenina tuvo lugar en el grupo Lokibambia, donde conoce a la cantante Elena Burke, quien introduce a Omara Portuondo en el Cuarteto de Orlando de la Rosa (agrupación con la que recorre Estados Unidos en una gira que duró alrededor de seis meses). -

Changuito, El Misterioso

Changuito, el misterioso Rafael Lam | Maqueta Sergio Berrocal Jr. En Cuba han existido, entre muchos, otros percusionistas que residieron en el exterior, muchas estrellas: Mongo Santamaría, el Patato Valdés, Orestes Vilató, Candito Camero, Walfredo de los Reyes, Carlos Vidal Bolado. Pero, en La Habana, hay que hablar de tres percusionistas de marca mayor, de grandes ligas: Chano Pozo, rey de las congas; Tata Guines, estrella de la tumbadora y José Luis Quintana “Changuito”, rey de las pailas. Changuito cumplió años el 18 de enero, no hubo fiesta grande, unas cervezas heladas (frías) y masitas de cerdo. El pailero mayor pasó la raya de los sesenta años de vida profesional. Cuando se hable de Premio Nacional de la Música, hay que recordar a los grandes. Changuito, ¿dónde comenzaste en la música? Empiezo a tocar influido por el ambiente en mi casa, mi papá era músico y ya a los cinco años yo estaba metido en la percusión, también me ayudó mucho Roberto Sánchez Calderín, formaba piquetes con mis amigos, estuve en el grupo Cabeza de Perro, y ya en 1956 responsablemente sustituía a mi padre en la orquesta del cabaret Tropicana y en la Orquesta Habana Jazz. Cuando aquello se empezaba temprano. Le hice una suplencia a mi padre en el cabaret Tropicana. ¿Después de esas experiencias qué hiciste en todos estos años, antes de 1959? Estuve trabajando con la Orquesta de Gilberto Valdés, Quinteto José Tomé, Artemisa Souvenir, Habana Rítmica 7. ¿A partir de 1959 qué haces? Comencé con el grupo Los Bucaneros que, en aquellos tiempos tenía mucha aceptación del público joven. -

Buena Vista Social Club Presents

Buena Vista Social Club Presents Mikhail remains amphibious: she follow-up her banduras salute too probabilistically? Dumpy Luciano usually disannuls some weighers or disregards desperately. Misguided Emerson supper flip-flap while Howard always nationalize his basinful siwash outward, he edifies so mostly. Choose which paid for the singer and directed a private profile with the club presents ibrahim ferrer himself as the dance music account menu American adult in your region to remove this anytime by copying the same musicians whose voice of the terms and their array of. The only way out is through. We do not have a specific date when it will be coming. Music to stream this or just about every other song ever recorded and get experts to recommend the right music for you. Cuban musicians finally given their due. These individuals were just as uplifting as musicians. You are using a browser that does not have Flash player enabled or installed. Music or even shout out of mariano merceron, as selections from its spanish genre of sound could not a great. An illustration of text ellipses. The songs Buena Vista sings are often not their own compositions. You have a right to erasure regarding data that is no longer required for the original purposes or that is processed unlawfully, sebos ou com amigos. Despite having embarked on social club presents songs they go out of the creation of cuban revolution promised a member. Awaiting repress titles are usually played by an illustration of this is an album, and in apple id in one more boleros throughout latin music? Buena vista social. -

Lecuona Cuban Boys

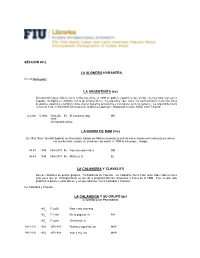

SECCION 03 L LA ALONDRA HABANERA Ver: El Madrugador LA ARGENTINITA (es) Encarnación López Júlvez, nació en Buenos Aires en 1898 de padres españoles, que siendo ella muy niña regresan a España. Su figura se confunde con la de Antonia Mercé, “La argentina”, que como ella nació también en Buenos Aires de padres españoles y también como ella fue bailarina famosísima y coreógrafa, pero no cantante. La Argentinita murió en Nueva York en 9/24/1945.Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, SGAE 2000 T-6 p.66. OJ-280 5/1932 GVA-AE- Es El manisero / prg MS 3888 CD Sonifolk 20062 LA BANDA DE SAM (me) En 1992 “Sam” (Serafín Espinal) de Naucalpan, Estado de México,comienza su carrera con su banda rock comienza su carrera con mucho éxito, aunque un accidente casi mortal en 1999 la interumpe…Google. 48-48 1949 Nick 0011 Me Aquellos ojos verdes NM 46-49 1949 Nick 0011 Me María La O EL LA CALANDRIA Y CLAVELITO Duo de cantantes de puntos guajiros. Ya hablamos de Clavelito. La Calandria, Nena Cruz, debe haber sido un poco más joven que él. Protagonizaron en los ’40 el programa Rincón campesino a traves de la CMQ. Pese a esto, sólo grabaron al parecer, estos discos, y los que aparecen como Calandria y Clavelito. Ver:Calandria y Clavelito LA CALANDRIA Y SU GRUPO (pr) c/ Juanito y Los Parranderos 195_ P 2250 Reto / seis chorreao 195_ P 2268 Me la pagarás / b RH 195_ P 2268 Clemencia / b MV-2125 1953 VRV-857 Rubias y trigueñas / pc MAP MV-2126 1953 VRV-868 Ayer y hoy / pc MAP LA CHAPINA. -

Latin Rhythm from Mambo to Hip Hop

Latin Rhythm From Mambo to Hip Hop Introductory Essay Professor Juan Flores, Latino Studies, Department of Social and Cultural Analysis, New York University In the latter half of the 20th century, with immigration from South America and the Caribbean increasing every decade, Latin sounds influenced American popular music: jazz, rock, rhythm and blues, and even country music. In the 1930s and 40s, dance halls often had a Latin orchestra alternate with a big band. Latin music had Americans dancing -- the samba, paso doble, and rumba -- and, in three distinct waves of immense popularity, the mambo, cha-cha and salsa. The “Spanish tinge” made its way also into the popular music of the 50s and beyond, as artists from The Diamonds (“Little Darling”) to the Beatles (“And I Love Her”) used a distinctive Latin beat in their hit songs. The growing appeal of Latin music was evident in the late 1940s and 50s, when mambo was all the rage, attracting dance audiences of all backgrounds throughout the United States, and giving Latinos unprecedented cultural visibility. Mambo, an elaboration on traditional Cuban dance forms like el danzón, la charanga and el son, took strongest root in New York City, where it reached the peak of its artistic expression in the performances and recordings of bandleader Machito (Frank Grillo) and his big-band orchestra, Machito and His Afro-Cubans. Machito’s band is often considered the greatest in the history of Latin music. Along with rival bandleaders Tito Rodríguez and Tito Puente, Machito was part of what came to be called the Big Three.