Guide-Linee-E-Modello-Integrato.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Ricordo Di Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa

NEW La newsletter del Presidio “Luigi Ioculano” di Cuorgné SETTEMBRE 2012 N° 5 Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa, l’esempio di un uomo vero « ... ci sono cose che non si fanno per coraggio . Si fanno per potere continuare a guardare serenamente negli occhi i propri figli e i figli dei propri figli. C’è troppa gente onesta, tanta gente qualunque, che ha fiducia in me. Non posso deluderla. » (Carlo Alberto dalla Chiesa al figlio, citato in 'Delitto imperfetto' di Nando dalla Chiesa, 1984) Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa, indagare su ben 74 omicidi, tra legione carabinieri di Palermo. I generale dei Carabinieri, nasce a cui quello di Placido Rizzotto, risultati, come ci si aspetta da Saluzzo, in provincia di Cuneo, il sindacalista socialista. Dalla Chiesa, non mancano: 27 settembre del 1920. Figlio di Alla fine del 1949 Dalla Chiesa un carabiniere, vice comandante indicherà Luciano Liggio come assicura alla giustizia boss generale dell'Arma, non frequenta responsabile dell'omicidio. Per i malavitosi come Gerlando Alberti l'accademia e passa nei carabinieri suoi ottimi risultati riceverà una e Frank Coppola. Iniziando come ufficiale di complemento Medaglia d'Argento al Valor inoltre a investigare sulle presunte allo scoppio della Seconda guerra Militare. relazioni fra mafia e politica. mondiale. In seguito viene trasferito a Nel 1968 con i suoi reparti Nel settembre del 1943 sta Firenze, poi a Como e Milano. interviene nel Belice in soccorso ricoprendo il ruolo di comandante Nel 1963 è a Roma con il grado di alle popolazioni colpite dal sisma: a San Benedetto del Tronto, tenente colonnello. Poi si sposta gli viene consegnata una medaglia quando passa con la Resistenza ancora, a Torino, trasferimento di bronzo al valor civile per la partigiana. -

RPG Phd Thesis

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/85513 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Peña González R. Title: Order and Crime: Criminal Groups ́ Political Legitimacy in Michoacán and Sicily Issue Date: 2020-02-20 Chapter 5. Cosa Nostra: Tracking Sicilian Mafia’s Political Legitimacy At 2012, El Komander, popular Mexican "narco-singer", released his new single entitled "La mafia se sienta en la mesa" (Mafia Takes a Sit on the Table). El Komander, the artistic name of Alfredo Ríos, as well as other performers of the so-called narcocorridos (or, as it was later named, movimiento alterado) were forbidden to perform public concerts in Mexico. That was also the case in Michoacán, where a local public officer argued that Komander's ban was due to the lyric´s songs, which touch "very sensitive topics" (Velázquez, 2018). Certainly, most of his songs are dedicated to assert Mexican "narcos" as stylish and brave popular heroes. However, the lyrics of "La mafia se sienta a la mesa" were slightly different. Instead of glorifying exclusively Mexican “narcos”, this song did “[…] a twentieth-century history seen from the mafia’s point of view” (Ravveduto, 2014), in which “someone” in Sicily did start “everything”: “En un pueblito en Sicilia, un hombre empezó las cosas. Fue el padrino en la familia y fundó la Cosa Nostra. Desde Italia a Nueva York, traficó vino y tabaco. La mafia lo bautizó, fue el primer capo de capos” (In a small town in Sicily, a man started everything. He was the godfather in the family, and founded the Cosa Nostra. -

Comunicato Stampa ‘La Festa Dell’Onesta’ – Palermo, 3 Settembre 2017

COMUNICATO STAMPA ‘LA FESTA DELL’ONESTA’ – PALERMO, 3 SETTEMBRE 2017 Palermo, 28 luglio – Nando Dalla Chiesa, figlio del Generale Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa; Franco La Torre, figlio di Pio La Torre; Francesco Puglisi, fratello di padre Pino Puglisi; il Prefetto Guido Longo. Sono solo alcuni dei protagonisti della seconda edizione della ‘Festa dell’Onestà’, che si svolgerà a Palermo il prossimo 3 settembre. E poi, presentazioni di libri, laboratori di pittura per bambini, mostre, momenti di confronto, musica e tanto altro. Una giornata speciale, nel cuore del Cassaro, per onorare la memoria del Generale Dalla Chiesa, della moglie Emanuela Setti Carraro e dell’agente di scorta Domenico Russo, nel giorno del 35° anniversario dell’omicidio di via Isidoro Carini. Memoria, appunto. Sarà questo il tema della Festa dell’Onestà di quest’anno, come l’hashtag creato per l’evento: #memoria. Un evento organizzato dall’Associazione ‘Cassaro Alto’, insieme con il Comune di Palermo ed il contributo di Gesap e Confcommercio. Teatro della manifestazione sarà il Cassaro, con la sua storia, i suoi negozi, i suoi librai e la Biblioteca Centrale della Regione Siciliana, che avrà un ruolo importante con l’istituzione di un ‘Fondo Dalla Chiesa’. “Palermo non è più quella del 1982 – ha sottolineato il Sindaco Leoluca Orlando, durante la conferenza stampa di oggi – Palermo è cambiata, anche se questo processo non è ancora concluso. Ma credo sia questa la Palermo che il Generale Dalla Chiesa immaginava in quegli anni di stragi, di sangue, di sottosviluppo e marginalità. E la Festa dell’Onestà è il modo migliore per ricordarlo”. -

The Code of Ethics for Sport in the Municipality of Milan: a Grassroots Approach Against Organised Crime and Corruption in Sports

This content is drawn from Transparency International’s forthcoming Global Corruption Report: Sport. For more information on our Corruption in Sport Initiative, visit: www.transparency.org/sportintegrity The Code of Ethics for sport in the Municipality of Milan: a grassroots approach against organised crime and corruption in sports Paolo Bertaccini Bonoli and Caterina Gozzoli1 The problem The city of Milan and the Lombardy region are traditional areas of industry and professional services, providing approximately 25% of Italy’s GDP, and are historically characterised by a respect for the rule of law. However, the last decade has witnessed a gradual increase in organised crime,2 with judicial investigations repeatedly uncovering the presence of the Mafia in building, waste cycle management, trade, major infrastructure projects and retail commerce. Greater attention was drawn in early 2014 in connection with the organisation of Expo 2015 in Milan, when serious cases of corruption surfaced.3 Nonetheless, it still surprised many in Milan that organised crime extended to the world of grassroots sport. In March 2011 the Ripamonti sports facility in via Iseo was impounded as part of the Milanese anti-Mafia operation ‘Redux-Caposaldo’.The operation found that the facility was being managed by the Flachi clan, ‘which exercises all the powers typical of dominus: deciding on staff, resolving disputes, managing services and raking in the profits. And the City, as the owner of the centre, was unaware that it was funding the Flachi group by supporting its economic initiatives.’4 As a result of the seizure, the facility was closed by the prefetto (the central state authority) and the licence was revoked by the municipality. -

TERROR VANQUISHED the Italian Approach to Defeating Terrorism

TERROR VANQUISHED The Italian Approach to Defeating Terrorism SIMON CLARK at George Mason University TERROR VANQUISHED The Italian Approach to Defeating Terrorism Simon Clark Copyright ©2018 Center for Security Policy Studies, Schar School of Policy and Government, George Mason University Library of Congress Control Number: 2018955266 ISBN: 978-1-7329478-0-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from: The Center for Security Policy Studies Schar School of Policy and Government George Mason University 3351 Fairfax Avenue Arlington, Virginia 22201 www.csps.gmu.edu PHOTO CREDITS Cover: Dino Fracchia / Alamy Stock Photo Page 30: MARKA / Alamy Stock Photo Page 60: The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo Page 72: Dino Fracchia / Alamy Stock Photo Page 110: Dino Fracchia / Alamy Stock Photo Publication design by Lita Ledesma Contents Foreword 5 Preface 7 Introduction 11 Chapter 1: The Italian Approach to Counter-Terrorism 21 Chapter 2: Post War Italian Politics: Stasis And Chaos 31 Chapter 3: The Italian Security Apparatus 43 Chapter 4: Birth of the Red Brigades: Years of Lead 49 Chapter 5: Attacking the Heart of the State 61 Chapter 6: Escalation, Repentance, Defeat 73 Chapter 7: State Sponsorship: a Comforting Illusion 81 Chapter 8: A Strategy for Psychological Warfare 91 Chapter 9: Conclusion: Defeating A Terrorist Threat 111 Bibliography 119 4 Terror Vanquished: The Italian Approach to Defeating Terrorism Foreword 5 Foreword It is my pleasure to introduce Terrorism Vanquished: the Italian Approach to Defeating Terror, by Simon Clark. In this compelling analysis, Mr. -

Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa. L'esempio Di Un Uomo/12

35 GIOVEDÌ 24 DICEMBRE 2009 IL DIZIONARIO DELLA MAFIA STATO/12 Carlo Alberto dalla Chiesa L’esempio di un uomo Una vita in trincea UN SISTEMA COSÌ LONTANO DAL SUD IL SENSO PROFONDO DI UNA PAROLA Nicola Tranfaglia STORICO adefinizioneèchiarafindalMe- dioevo: «persona giuridica territo- L riale sovrana costituita dall’orga- nizzazione politica di un gruppo sociale stanziato stabilmente su un territo- rio». Ed emerge già da quel che scrivono in Italia Dante Alighieri e più tardi Machia- velli ma la storia italiana ci mette molti se- coli per dare alla lingua e alla nazione la consistenza che occorre a uno Stato. Anzi èproprioilsegretariofiorentino(lostesso Machiavelli) alla fine del Quattrocento a precisare il significato del vocabolo che di- venta popolare nel Cinquecento. La discus- sione cresce nei secoli successivi e l’aggetti- vazione è quella che chiarisce i problemi legati alla nascita come alle trasformazio- ni dello Stato. La storia italiana è contrassegnata dalla lentezza nella nascita di quello che è consi- derato lo Stato moderno inteso come espressione di un progresso che allontana dal dominio di un uomo o di una famiglia sola. E spesso gli storici mettono in connes- sione le difficoltà di nascita dello stato mo- derno nel Mezzogiorno e nelle isole con lo sviluppo dei fenomeni mafiosi, che mo- strano peraltro grande capacità di adatta- mento all’evoluzione dello Stato e al suo modo di funzionare. Alcuni studiosi hanno parlato a lungo, proprio in relazione a nascita e sviluppo di associazioni mafiose, di “assenza” o “lontananza dello Stato” come ragioni di Uno «strenuo combattente» crescita da parte di queste associazioni. -

ORGANIZED CRIME in OSTIA. a THEORETICAL NOTE Ilaria Meli

La ricerca 1 ORGANIZED CRIME IN OSTIA. A THEORETICAL NOTE Ilaria Meli Abstract Even if only recently public opinion is focalizing on Ostia, this criminal context had been very problematic since the 1970s. Here several criminal organizations cohabit, fight and shared power and areas of influence. But what made very particular this municipality is the presence of very strong and well embedded local mafias (autochthonous criminal groups that adopt mafia model, without any link with traditional organizations). These groups had been developed also in others Italian region, but in Rome seems to be permanent and stronger (sometime also stronger than traditional mafias). So, this paper proposes an analysis of local mafias embedded model in a non-traditional territory, and in particular it is presented a case study on Ostia. Keywords: Territory, local mafias, Ostia, non-traditional areas, mafia model 1. Local roots and international trafficking. The framework of a debate Even if traditional mafia organizations (Cosa nostra, ‘ndrangheta e camorra) originally arose – respectively - in Sicilian and Calabrese agricultural areas and in Napoli’s popular quarters during the Bourbons period, they have been able to emerge and succeed in very different contexts too. This paper proposes a cause of reflection on the mafia model expansion process and its efficiency and in particular, it is focalized on the phenomenon of the autochthonous mafia groups. In order to do so, the most interesting field of study is the city of Rome, due to the fact here coexist – almost always – pacifically traditional mafias and local ones. However differently from what literature says on the latter, sometimes those are able to be stronger and better embedded in the territory than the first ones. -

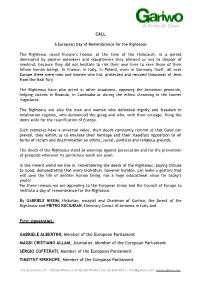

Gariwo's Call

CALL A European Day of Remembrance for the Righteous The Righteous saved Europe’s honour at the time of the Holocaust: in a period dominated by passive onlookers and slaughterers they allowed us not to despair of mankind, because they did not hesitate to risk their own lives to save those of their fellow human beings. In France, in Italy, in Poland, even in Germany itself, all over Europe there were men and women who hid, protected and rescued thousands of Jews from the Nazi fury. The Righteous have also acted in other situations, opposing the Armenian genocide, helping victims in Rwanda, in Cambodia or during the ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia. The Righteous are also the men and women who defended dignity and freedom in totalitarian regimes, who denounced the gulag and who, with their courage, flung the doors wide for the reunification of Europe. Such examples have a universal value, their deeds constantly remind us that Good can prevail, they exhort us to emulate their heritage and their steadfast opposition to all forms of racism and discrimination on ethnic, social, political and religious grounds. The deeds of the Righteous stand as warnings against persecution and for the prevention of genocide wherever its pernicious seeds are sown. In the violent world we live in, remembering the deeds of the Righteous, paying tribute to Good, demonstrating that every individual, however humble, can make a gesture that will save the life of another human being, has a huge educational value for today’s youth! For these reasons we are appealing to the European Union and the Council of Europe to institute a day of remembrance for the Righteous. -

Doctoral Research Seminar EMUNI University

Doctoral Research Seminar EMUNI University University of Genoa, Faculty of Political Sciences 18-23 July 2011 Civil Rights Protection and the Rights of Migrants in the Framework of the Mediterranean Cooperation Monday 18 July 2011 9 to 10: Openings GIACOMO DEFERRARI, Rector of the University of Genoa M. MARSONET, Vice - Rector for International Relations G. B. VARNIER, Dean of the Faculty of Political Sciences NANDO DALLA CHIESA, University of Milan, Co-ordinator of the Project “Genova città dei diritti” 10 to 10.45: JOSEPH MIFSUD (President of EMUNI University – Slovenia), European Neighbourhood. The Mediterranean Perspective 10.45 to 11: Coffee break 11 to 11.45 G. GILIBERTI (University of Urbino, Member of EMUNI University’s Senate), The EMUNI University and Euro-Mediterranean Relations 11.45 to 12.30 G. GRIMALDI (University of Aosta), The EU and the Mediterranean Space between Partnership, Cooperation and Inter-regional Integration 2.30 to 3.15 pm G. CARLINI (University of Genoa), Interculturalité et société civile dans la Méditerrané 3.15 to 4.00 pm A. BCHIR (University of Tunis - Tunisia), La question des droits humains et civils entre la politique légitimiste (la dictature), l’option libérale (la mondialisation) et la montée de l’islamisme politique en Tunisie 1 4.00 to 4.45 pm A. BALLERINI (Lawyer in Genoa), Immigration: between Rights and Obligations 4.45 to 5.30 pm A. PIRNI (University of Genoa), The “M” Factor in Otherness Social Construction: Towards a Research Project 5.30 to 7 pm: Research paper preparation and bibliography research Tuesday 19 July 2011 9 to 10.30 am P. -

L'antimafia Come Risorsa Politica

Lʼantimafia come risorsa politica 28/02/19, 10)18 Laboratoire italien Politique et société 22/2019 « Sans recourir à la violence » : la société italienne face aux terrorismes et aux mafias (1969-1992) Dossier L’antimafia come risorsa politica L’antimafia comme ressource politique Antimafia as a political resource ANTONINO BLANDO Résumés Italiano Français English In questo saggio si discute un momento particolare della storia dell’antimafia. Si tratta degli anni 1985-1994, che hanno come figura principale Leoluca Orlando, sindaco di Palermo. In quel periodo storico, per la prima volta, il discorso politico dell’antimafia viene fatto proprio da questo giovane leader della Democrazia cristiana. Il partito era stato al governo di Palermo e dell’Italia dal secondo dopoguerra senza porsi il problema della lotta alla mafia. Sin all’inizio del 1980, erano state le forze di opposizioni, in particolare il Partito comunista e i sindacati, a portare avanti la lotta antimafia. Con l’omicidio di Piersanti Mattarella, presidente della Regione siciliana, e poi di Carlo Alberto dalla Chiesa, prefetto a Palermo, la Democrazia cristiana, guidata in Sicilia, da Sergio Mattarella (fratello di Piersanti), decise di tagliare i rapporti con la mafia, in particolare con Vito Ciancimino, ex sindaco capo-mafia di Palermo. L’esperienza di Orlando è prima di tutto il frutto di quella politica e poi di uno scontro nazionale, per la leadership governativa, tra Democrazia cristiana e Partito socialista. Tuttavia, nel 1994, con la fine della Prima Repubblica, l’antimafia non è stata più il principale terreno di confronto tra le forze politiche impegnate a contendersi il comune di Palermo. -

THE ANTIMAFIA MOVEMENT in ITALY. HISTORY and IDENTITY: a FOCUS on the GENDER DIMENSION Nando Dalla Chiesa

Saggio THE ANTIMAFIA MOVEMENT IN ITALY. HISTORY AND IDENTITY: A FOCUS ON THE GENDER DIMENSION Nando dalla Chiesa Title: The Antimafia Movement in Italy. History and Identity: a Focus on the Gender Dimension Gender and Generation. Abstract For many years now the Antimafia movement has been one of the most significant forms of collective movement in Italy. It is a coherent and lasting social movement, perhaps one of the largest in Europe, but it is struggling to find its place in academic studies. This article reviews its fundamental phases and protagonists, underlining the extraordinary role historically played by women and new generations and especially analysing the forms of female contribution. Key words: Antimafia movement; history; identity; women; new generations Da molti anni il movimento Antimafia rappresenta una tra le forme più significative di movimento collettivo in Italia. Si tratta di un movimento coerente e duraturo, forse tra i più grandi in Europa, che tuttavia fatica a trovare un suo spazio negli studi accademici. Il presente articolo ne ripercorre le fasi e i protagonisti fondamentali, sottolineando il ruolo straordinario storicamente rivestito dalle donne e dalle giovani generazioni e analizzando in particolare le forme del contributo femminile. Parole chiave: movimento antimafia; storia; identità; donne; nuove generazioni 6 Cross Vol.6 N°4 (2020) - DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13130/cross-15339 Saggio Introduction Italy is home to a phenomenon known the world over: The Mafia. As scholars know, the name first appeared in a theatrical piece staged in Palermo in 1863 (I mafiusi di la Vicaria), and immediately became part of the official Italian language.1 After a short time it also contributed to shaping Italy’s image worldwide and increasingly conditioned and influenced Italian life: culturally, socially, politically, economically, and institutionally.2 All this is well known. -

RESEARCH NOTE a Book Festival Dedicated to the Mafia(S)

View metadata,CMIT citation 806141—23/5/2013—CHANDRAN.C—451693———Style and similar papers at core.ac.uk 2 brought to you by CORE provided by Institutional Research Information System University of Turin Modern Italy, 2013 Vol. 00, No. 0, 1–6, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13532944.2013.806141 1 2 3 4 RESEARCH NOTE 5 6 A book festival dedicated to the Mafia(s): a report from the first two editions 7 of the Trame Festival, Lamezia Terme, 2011–2012 8 a b 9 Vittorio Mete * and Rocco Sciarrone 10 aDepartment of Law and Social Sciences, University Magna Græcia of Catanzaro, Catanzaro, Italy; [Q1]11 bDepartment of Social and Political Sciences, University of Turin, Turin, Italy 12 13 (Received 4 February 2013; final version accepted 14 April 2013 ) 14 This article provides a detailed report on the first two editions of the festival of books 15 about the Mafia held in Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Italy) in June 2011 and June 2012. 16 The article reviews the 101 books presented in the two festivals. The analysis of the 17 books presented at the public event gives us the opportunity to analyse the ways in 18 which the Mafia’s public image has been constructed in recent times. The books 19 presented at the first two Festival editions have been divided by the authors into four main categories: books written by journalists, by magistrates, by Mafia researchers and 20 books by activists from the anti-mafia movement. The debate on Mafia and anti-mafia 21 seems to have a number of different ‘voices’, some of which (like those of magistrates 22 and journalists) prevail over others, and this has led to a public debate about organised 23 crime at a series of levels.