Racist Encounters: a Pragmatist Semiotic Analysis of Interaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qualia NICHOLAS HARKNESS Harvard University, USA

Qualia NICHOLAS HARKNESS Harvard University, USA Qualia (singular, quale) are cultural emergents that manifest phenomenally as sensuous features or qualities. The anthropological challenge presented by qualia is to theorize elements of experience that are semiotically generated but apperceived as non-signs. Qualia are not reducible to a psychology of individual perceptions of sensory data, to a cultural ontology of “materiality,” or to philosophical intuitions about the subjective properties of consciousness. The analytical solution to the challenge of qualia is to con- sider tone in relation to the familiar linguistic anthropological categories of token and type. This solution has been made methodologically practical by conceptualizing qualia, in Peircean terms, as “facts of firstness” or firstness “under its form of secondness.” Inthephilosophyofmind,theterm“qualia”hasbeenusedtodescribetheineffable, intrinsic, private, and directly or immediately apprehensible experiences of “the way things seem,” which have been taken to constitute the atomic subjective properties of consciousness. This concept was challenged in an influential paper by Daniel Dennett, who argued that qualia “is a philosophers’ term which fosters nothing but confusion, and refers in the end to no properties or features at all” (Dennett 1988, 387). Dennett concluded, correctly, that these diverse elements of feeling, made sensuously present atvariouslevelsofattention,wereactuallyidiosyncraticresponsestoapperceptions of “public, relational” qualities. Qualia were, in effect, -

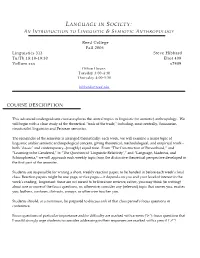

Language in Society: an Introduction to Linguistic & Semiotic Anthropology

LANGUAGE IN SOCIETY: AN INTRODUCTION TO LINGUISTIC & SEMIOTIC ANTHROPOLOGY Reed College Fall 2006 Linguistics 313 Steve Hibbard Tu/Th 18:10‐19:30 Eliot 409 Vollum xxx x7489 Office Hours: Tuesday 3:00‐4:30 Thursday 4:00‐5:30 [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION This advanced undergraduate course explores the central topics in linguistic (or semiotic) anthropology. We will begin with a close study of the theoretical ʺtools of the trade,ʺ including, most centrally, Saussurian structuralist linguistics and Peircean semiotics. The remainder of the semester is arranged thematically: each week, we will examine a major topic of linguistic and/or semiotic anthropological concern, giving theoretical, methodological, and empirical work‐‐ both ʺclassicʺ and contemporary‐‐(roughly) equal time. From “The Construction of Personhood,” and “Learning to be Gendered,” to “The Question of ‘Linguistic Relativity’,” and “Language, Madness, and Schizophrenia,” we will approach each weekly topic from the distinctive theoretical perspective developed in the first part of the semester. Students are responsible for writing a short, weekly reaction paper, to be handed in before each week’s final class. Reaction papers might be one page, or five pages—it depends on you and your level of interest in the week’s reading. Important: these are not meant to be literature reviews; rather, you may think (in writing) about one or more of the focus questions, or, otherwise, consider any (relevant) topic that moves you, excites you, bothers, confuses, distracts, annoys, or otherwise touches you. Students should, at a minimum, be prepared to discuss each of that class period’s focus questions in conference. -

Linguistic Anthropology in 2013: Super-New-Big

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST Linguistic Anthropology Linguistic Anthropology in 2013: Super-New-Big Angela Reyes ABSTRACT In this essay, I discuss how linguistic anthropological scholarship in 2013 has been increasingly con- fronted by the concepts of “superdiversity,” “new media,” and “big data.” As the “super-new-big” purports to identify a contemporary moment in which we are witnessing unprecedented change, I interrogate the degree to which these concepts rely on assumptions about “reality” as natural state versus ideological production. I consider how the super-new-big invites us to scrutinize various reconceptualizations of diversity (is it super?), media (is it new?), and data (is it big?), leaving us to inevitably contemplate each concept’s implicitly invoked opposite: “regular diversity,” “old media,” and “small data.” In the section on “diversity,” I explore linguistic anthropological scholarship that examines how notions of difference continue to be entangled in projects of the nation-state, the market economy, and social inequality. In the sections on “media” and “data,” I consider how questions about what constitutes lin- guistic anthropological data and methodology are being raised and addressed by research that analyzes new and old technologies, ethnographic material, semiotic forms, scale, and ontology. I conclude by questioning the extent to which it is the super-new-big itself or the contemplation about the super-new-big that produces perceived change in the world. [linguistic anthropology, superdiversity, new media, big data, -

Skeeling 1.Pdf

Musicking Tradition in Place: Participation, Values, and Banks in Bamiléké Territory by Simon Robert Jo-Keeling A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Judith T. Irvine, Chair Emeritus Professor Judith O. Becker Professor Bruce Mannheim Associate Professor Kelly M. Askew © Simon Robert Jo-Keeling, 2011 acknowledgements Most of all, my thanks go to those residents of Cameroon who assisted with or parti- cipated in my research, especially Theophile Ematchoua, Theophile Issola Missé, Moise Kamndjo, Valerie Kamta, Majolie Kwamu Wandji, Josiane Mbakob, Georges Ngandjou, Antoine Ngoyou Tchouta, Francois Nkwilang, Epiphanie Nya, Basil, Brenda, Elizabeth, Julienne, Majolie, Moise, Pierre, Raisa, Rita, Tresor, Yonga, Le Comité d’Etudes et de la Production des Oeuvres Mèdûmbà and the real-life Association de Benskin and Associa- tion de Mangambeu. Most of all Cameroonians, I thank Emanuel Kamadjou, Alain Kamtchoua, Jules Tankeu and Elise, and Joseph Wansi Eyoumbi. I am grateful to the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research for fund- ing my field work. For support, guidance, inspiration, encouragement, and mentoring, I thank the mem- bers of my dissertation committee, Kelly Askew, Judith Becker, Judith Irvine, and Bruce Mannheim. The three members from the anthropology department supported me the whole way through my graduate training. I am especially grateful to my superb advisor, Judith Irvine, who worked very closely and skillfully with me, particularly during field work and writing up. Other people affiliated with the department of anthropology at the University of Michigan were especially helpful or supportive in a variety of ways. -

Chapter 2 Style

Chapter 2 Style "Every apparition can be experienced in two ways. The two ways are not at random, but they are attached to the apparitions – they are derived from the nature of the apparition, from two of their characteristics: exterior – interior.” Wassily Kandinsky1 “Le style c’est l’homme même.” Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon2 Although people find it difficult to define the concept of style spontaneously, they classify each other as belonging or not belonging together by respective styles. They always do so when they see others as punk, nerd, hipster, hippie, yuppie, emo, or belonging to hip hop or the mainstream. Which succeeds more fre- quently than not! Yet, the question is how this works and why. Sociology asserts style to be either representative or constitutive of social groups, or else both.3 However, there is consensus in all of sociology that social 1 Kandinsky 1973 (1926), p. 13, my translation. 2 Cited after Saisselin 1958. 3 Modernist sociology regards differences in endowment (financial and cultural capital) as being constitutive for forming social groups; style is merely representative of social groups (for exam- ple, the Birmingham School in its analysis of British youth cultures [Hebdige 1988]). In contrast, in the postmodern variant of sociology, the group style is understood as the constituent charac- teristic of the group; it is only by showing a style, that groups can come into being and are able to persist; other socio-cultural characteristics, for example the endowment with capital, play no or only a secondary role. Bourdieu (1982) marks the transition from modernism to postmodernism, 48 Part 1: Culture of Dissimiarity groups and their style form an inseparable entity. -

Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity Krystal A

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 1-1-2015 Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity Krystal A. Smalls University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the African American Studies Commons, Anthropological Linguistics and Sociolinguistics Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Smalls, Krystal A., "Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2022. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2022 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2022 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity Abstract From the colonization of the “Dark Continent,” to the global industry that turned black bodies into chattel, to the total absence of modern Africa from most American public school curricula, to superfluous representations of African primitivity in mainstream media, to the unflinching state-sanctioned murders of unarmed black people in the Americas, antiblackness and anti-black racism have been part and parcel to modernity, swathing centuries and continents, and seeping into the tiny spaces and moments that constitute social reality for most black-identified -

Language in Culture Syllabus Petko Ivanov Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Slavic Studies Course Materials Slavic Studies Department 2015 Language in Culture Syllabus Petko Ivanov Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/slaviccourse Recommended Citation Ivanov, Petko, "Language in Culture Syllabus" (2015). Slavic Studies Course Materials. Paper 1. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/slaviccourse/1 This Course Materials is brought to you for free and open access by the Slavic Studies Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Slavic Studies Course Materials by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. C o n n e c t i c u t C o l l e g e Spring 2015 ANT/SLA 226 René Magritte This is not a pipe (1936) Language in Culture Prof. Petko Ivanov ANT 226: Language in Culture Connecticut College Spring 2015 ANT / SLA 226 Language in Culture Spring 2015, Wednesday/Friday 2:45-4:00 Olin 113 Foucault, Lacan, Lévi-Strauss, and Barthes Instructor: Petko Ivanov Blaustein 330, x5449, [email protected] Office hours W/F 1:30-2:30 and by appointment Course Description The course is an introduction to linguistic anthropology with a main focus on language “use” in society. Among the main topics to be addressed are the notions of language ideology (how language is conceptualized by its users, e.g., what they think they do with language when they talk and otherwise utilize their language); pragmatics and metapragmatics; socio-cultural semiosis of linguistic practices, incl. -

Introduction: QUALIA

Article Anthropological Theory 13(1/2) 3–11 ! The Author(s) 2013 Introduction: QUALIA Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Lily Hope Chumley DOI: 10.1177/1463499613483389 New York University, USA ant.sagepub.com Nicholas Harkness Harvard University Press, USA Abstract This special issue proposes that the semiotically theorized concept of ‘qualia’ is useful for anthropologists working on problems of the senses, materiality, embodiment, aes- thetics, and affect. Qualia are experiences of sensuous qualities (such as colors, tex- tures, sounds, and smells) and feelings (such as satiety, anxiety, proximity, and otherness). The papers in this issue, first presented in a conference in honor of Nancy Munn and her groundbreaking book, The Fame of Gawa: A Symbolic Study of Value Transformation in a Massim Society (1986), offer ethnographic accounts of the dis- cursive, historical, and political conditions under which sensations come to be under- stood as being sensations of qualities – the qualia of softness, lightness, clarity, pain, stink, etc. – and in which those qualia are endowed with cultural value, whether positive or negative. The papers in this issue demonstrate that qualia are not just subjective mental experiences but rather sociocultural events of ‘qualic’ – and qualitative – orien- tation and evaluation. These papers thus provide models for the analysis of experience by calling into question what counts for social groups as the senses, materiality or immateriality, interiority, embodiment, or exteriority. Keywords Nancy Munn, qualia, qualisign, C.S. Peirce Sociocultural anthropology has always been interested in the senses, materiality, embodiment, aesthetics, and affect. Our discipline is fundamentally concerned with the perceptible qualities of the world: looks, tastes, sounds, smells, and feels. -

Musical Meaning and Indexicality in the Analysis of Ceremonial Mbira Music

Semiotica 2020; 236–237: 55–83 Tony Perman* Musical meaning and indexicality in the analysis of ceremonial mbira music https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2018-0057 Abstract: In this essay I examine three different indexical processes that inform meaning during a mbira performance in Zimbabwe in order to clarify the nature of meaning in musical practice. I continue others’ efforts to provincialize language and correct the damage done by “symbolocentrism’s” continued reliance on post- Saussurian models of signification and structure by addressing processes of purpose, effect, and agency in meaning. Emphases on language and/or structure mislead explanations of musical meaning and compromise the understanding of meaning itself. By foregrounding the unique properties of indexicality in musical practice, and highlighting three distinct indexical processes that drive music’s meaning (deictic, metonym, and replica), I help free meaning from language and offer an ethnomu- sicological counterpoint to multidisciplinary efforts that define meaning within lin- guistic and physiological paradigms. Indexical meaning is direct but unpredictable, rooted in experience, embodied habits, and the here and now. Keywords: index, meaning, music, semiotics, Zimbabwe Broadly speaking, this essay is about musical meaning. More narrowly, it examines the nature of indices as defined by C. S. Peirce and their primary importance to musical inquiry relative to the limited relevance of his concept of symbols. More narrowly still, I ask whether one specific performance of the mbira piece “Shumba” at one particular ceremony in Zimbabwe can be explained via symbolism, or is more appropriately understood through different indexical processes. Despite flourishing in seemingly every community on earth for millennia and despite decades of thor- ough multidisciplinary attention, explanations for why musicking feels good and what it means remain elusive and fragmented for musicians, scholars, and critics.1 Music’s power is knowable, but seemingly unexplainable. -

Developments in Polynesian Ethnology

Developments in Polynesian Ethnology Developments in Polynesian Ethnology Edited by Alan Howard and Robert Borofsky Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824881962 (PDF) 9780824881955 (EPUB) This version created: 20 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. ©1989 University of Hawaii Press All rights reserved For Jan and Nancy CONTENTS Title Page ii Copyright 3 Dedication iv Acknowledgments vi 1. Introduction ALAN HOWARD AND ROBERT BOROFSKY 1 2. Prehistory PATRICK V. KIRCH 14 3. Social Organization ALAN HOWARD AND JOHN KIRKPATRICK 52 4. Socialization and Character Development JANE RITCHIE AND JAMES RITCHIE 105 5. Mana and Tapu BRADD SHORE 151 6. Chieftainship GEORGE E. MARCUS 187 7. Art and Aesthetics ADRIENNE L. KAEPPLER 224 8. The Early Contact Period ROBERT BOROFSKY AND ALAN HOWARD 257 9. Looking Ahead ROBERT BOROFSKY AND ALAN HOWARD 290 Bibliography 307 Contributors 407 Notes 410 v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A VARIETY of people contributed to the preparation of this book. -

SEMIOTIC ANTHROPOLOGY Fall 2016 Instructor: Dr

SOAN 236/323 SEMIOTIC ANTHROPOLOGY Fall 2016 Instructor: Dr. Sylvain Perdigon ([email protected], Nicely 201D) Semiotics, from the Greek sēmeion, is the study of all forms of activity, conduct or process that involve signs. Semiotic anthropology explores the role language and other sign systems plays in the ways we, the human animal, inhabit the world and our bodies, the ways we interact with each other, finally the ways in which power is distributed and operates in our everyday lives. As a distinct field of empirical research and theoretical inquiry, semiotic anthropology addresses fundamental questions about the place and workings of signs in the human form(s) of life. How to understand, for example, the relationship between the many kinds of signs that we use in the course of our everyday life, and what these signs stand for or represent? If our ability to make sense to each other depends on the stability of this relationship, how is this stability achieved across a multitude of sign-users? And how to account for the extraordinary force, too, that signs can acquire in our interactions, as demonstrated in the efficacy of religious and other rituals, the devastating impact of spells or insults, or the hold some words (e.g. “man” or “woman”) come to have on our intimate sense of who we are and what we can do? While we humans like to revel in our unique ability to create signs, are we not, just as much, the creation of the signs that we inherited and put to use? In dealing with such questions, and by looking at the multiple answers they have received in a variety of social and cultural worlds, semiotic anthropology has developed a powerful set of conceptual and methodological tools that can be applied to a wide range of sociocultural contexts and questions. -

Angela Reyes

Angela Reyes CONTACT INFORMATION Department of English Email: [email protected] Hunter College, CUNY Office: (212) 772-5076 695 Park Avenue Webpage: hunter.cuny.edu/english/angela-reyes New York, NY 10065 POSITIONS HELD Chair, 2018–2019, 2020–present (on leave 2020–2021) Professor, 2016–present Associate Professor, 2008–2016 Assistant Professor, 2003–2007 Department of English, Hunter College, CUNY Doctoral Faculty, 2011–present Program in Anthropology, CUNY Graduate Center Visiting Scholar, 2016, 2017 Department of English and Applied Linguistics, De La Salle University, Manila, Philippines Associate Editor for Linguistic Anthropology, 2016–2020 American Anthropologist Associate Editor, 2014–2016 Language in Society EDUCATION Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania, Educational Linguistics, with Distinction, 2003 Dissertation: “‘The Other Asian’: Linguistic, Ethnic and Cultural Stereotypes at an After-school Asian American Teen Videomaking Project.” Committee: Nancy H. Hornberger, Stanton Wortham, and Asif Agha M.S.Ed., University of Pennsylvania, Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages, 2000 Thesis: “English for Citizenship: Preparing Adult Vietnamese ESL Learners for the INS Exam” B.A., Michigan State University, Interdisciplinary Humanities, with Honors, 1992 BOOKS AND VOLUMES Wortham, Stanton and Angela Reyes (2021) Discourse Analysis Beyond the Speech Event, 2nd Edition. New York: Routledge. Alim, H. Samy, Angela Reyes, and Paul V. Kroskrity (Eds.) (2020) The Oxford Handbook of Language and Race. New York: Oxford University Press. Angela Reyes, 1 of 15 Wortham, Stanton and Angela Reyes (2015) Discourse Analysis Beyond the Speech Event. New York: Routledge. *Awarded the 2016 Edward Sapir Book Prize, Society for Linguistic Anthropology, American Anthropological Association. Alim, H. Samy and Angela Reyes (Eds.) (2011) Complicating Race: Articulating Race Across Multiple Social Dimensions.