Music, Language, and Texts: Sound and Semiotic Ethnography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Causes of Language Frames, Biases, and Cultural Transmission

Natural causes of language Frames, biases, and cultural transmission N. J. Enfield language Conceptual Foundations of science press Language Science 1 Conceptual Foundations of Language Science Series editors Mark Dingemanse, Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics N. J. Enfield, University of Sydney Editorial board Balthasar Bickel, University of Zürich, Claire Bowern, Yale University, Elizabeth Couper-Kuhlen, University of Helsinki, William Croft, University of New Mexico, Rose-Marie Déchaine, University of British Columbia, William A. Foley, University of Sydney , William F. Hanks, University of California at Berkeley, Paul Kockelman, Yale University, Keren Rice, University of Toronto, Sharon Rose, University of California at San Diego, Frederick J. Newmeyer, University of Washington, Wendy Sandler, University of Haifa, Dan Sperber Central European University No scientific work proceeds without conceptual foundations. In language science, our concepts about language determine our assumptions, direct our attention, and guide our hypotheses and our reasoning. Only with clarity about conceptual foundations can we pose coherent research questions, design critical experiments, and collect crucial data. This series publishes short and accessible books that explore well-defined topics in the conceptual foundations of language science. The series provides a venue for conceptual arguments and explorations that do not require the traditional book- length treatment, yet that demand more space than a typical journal article allows. In this series: 1. N. J. Enfield. Natural causes of language. Natural causes of language Frames, biases, and cultural transmission N. J. Enfield language science press N. J. Enfield. 2014. Natural causes of language: Frames, biases, and cultural transmission (Conceptual Foundations of Language Science 1). Berlin: Language Science Press. -

Qualia NICHOLAS HARKNESS Harvard University, USA

Qualia NICHOLAS HARKNESS Harvard University, USA Qualia (singular, quale) are cultural emergents that manifest phenomenally as sensuous features or qualities. The anthropological challenge presented by qualia is to theorize elements of experience that are semiotically generated but apperceived as non-signs. Qualia are not reducible to a psychology of individual perceptions of sensory data, to a cultural ontology of “materiality,” or to philosophical intuitions about the subjective properties of consciousness. The analytical solution to the challenge of qualia is to con- sider tone in relation to the familiar linguistic anthropological categories of token and type. This solution has been made methodologically practical by conceptualizing qualia, in Peircean terms, as “facts of firstness” or firstness “under its form of secondness.” Inthephilosophyofmind,theterm“qualia”hasbeenusedtodescribetheineffable, intrinsic, private, and directly or immediately apprehensible experiences of “the way things seem,” which have been taken to constitute the atomic subjective properties of consciousness. This concept was challenged in an influential paper by Daniel Dennett, who argued that qualia “is a philosophers’ term which fosters nothing but confusion, and refers in the end to no properties or features at all” (Dennett 1988, 387). Dennett concluded, correctly, that these diverse elements of feeling, made sensuously present atvariouslevelsofattention,wereactuallyidiosyncraticresponsestoapperceptions of “public, relational” qualities. Qualia were, in effect, -

Confessional Reflexivity As Introspection and Avowal

Establishing the ‘Truth’ of the Matter: Confessional Reflexivity as Introspection and Avowal JOSEPH WEBSTER University of Edinburgh The conceptualisation of reflexivity commonly found in social anthropology deploys the term as if it were both a ‘virtuous’ mechanism of self‐reflection and an ethical technique of truth telling, with reflexivity frequently deployed as an moral practice of introspection and avowal. Further, because reflexivity is used as a methodology for constructing the authority of ethnographic accounts, reflexivity in anthropology has come to closely resemble Foucault’s descriptions of confession. By discussing Lynch’s (2000) critical analysis of reflexivity as an ‘academic virtue’, I consider his argument through the lens of my own concept of ‘confessional reflexivity’. While supporting Lynch’s diagnosis of the ‘problem of reflexivity’, I attempt to critique his ethnomethodological cure as essentialist, I conclude that a way forward might be found by blending Foucault’s (1976, 1993) theory of confession with Bourdieu’s (1992) theory of ‘epistemic reflexivity’. The ubiquity of reflexivity and its many forms For as long as thirty years, reflexivity has occupied a ‘place of honour’ at the table of most social science researchers and research institutions. Reflexivity has become enshrined as a foundational, or, perhaps better, essential, concept which is relied upon as a kind of talisman whose power can be invoked to shore up the ‘truthiness’ of the claims those researchers and their institutions are in the business of making. No discipline, it seems, is more guilty of this ‘evoking’ than social anthropology (Lucy 2000, Sangren 2007, Salzaman 2002). Yet, despite the ubiquity of its deployment in anthropology, the term ‘reflexivity’ remains poorly defined. -

The Society of Linguistic Anthropology

Anthropology News February 2000 SECTION NEWS Emory U, Georgia Institute of Technology and in anthropology is marginal and he considers his anthropological approaches. Likewise, I have International Society for the Study of Narrative main interests as sociolinguistics. learned greatly from their dedication to studies of Literature will sponsor an International Confer- At the U of Auckland, until very recently, lin- NZ English, Maori and languages of the Pacific. ence on Narrative Apr 6-9,2000. See the Meeting guists belonged to two departments: English and Calendar for further details. Anthropology. Now, all linguists belong to a Us@l Addresses. Susan Gal, SLA Presidenl;.Dept Lmguistics Dept. I still have limited knowledge of of Anth, U of Chicago, 1126 E 59th St, Chicago IL Sociolinguistics and Anthropology in these liiguists, but my understanding is that 60637-1539; [email protected]. New Zealand those who were under the English department Alessandm Wanti, Journal of Linguistic An- are mostly formal (Chomskian) people, whereas thropology Edim; Dept of Anth, UCLA,CA 90095- By Yukako Sunaoshi (V of Auckland, New Zealand) those who were under the Anthropology depart- 1553; [email protected]. As an American-trained sociolinguist, I wasn’t ment are mostly descriptive people. It should be Laura Milk, SLA Progrmn Orgrmizer;.Dept of Soc sure what to expect when I first arrived in New noted, however, that many of these linguists are and Anthm, Lopla U, 6525 North Sheridan Road, Zealand. What I found was people doing very interested in the sociocultural aspects of language Chicago, IL 60626; tel 773/508-3469, fax 508- interesting work in sociolinguistics, but very little use and that the division between formal and 7099, lmil&[email protected]. -

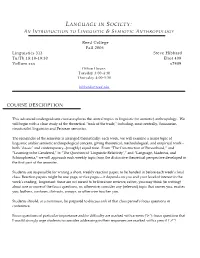

Language in Society: an Introduction to Linguistic & Semiotic Anthropology

LANGUAGE IN SOCIETY: AN INTRODUCTION TO LINGUISTIC & SEMIOTIC ANTHROPOLOGY Reed College Fall 2006 Linguistics 313 Steve Hibbard Tu/Th 18:10‐19:30 Eliot 409 Vollum xxx x7489 Office Hours: Tuesday 3:00‐4:30 Thursday 4:00‐5:30 [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION This advanced undergraduate course explores the central topics in linguistic (or semiotic) anthropology. We will begin with a close study of the theoretical ʺtools of the trade,ʺ including, most centrally, Saussurian structuralist linguistics and Peircean semiotics. The remainder of the semester is arranged thematically: each week, we will examine a major topic of linguistic and/or semiotic anthropological concern, giving theoretical, methodological, and empirical work‐‐ both ʺclassicʺ and contemporary‐‐(roughly) equal time. From “The Construction of Personhood,” and “Learning to be Gendered,” to “The Question of ‘Linguistic Relativity’,” and “Language, Madness, and Schizophrenia,” we will approach each weekly topic from the distinctive theoretical perspective developed in the first part of the semester. Students are responsible for writing a short, weekly reaction paper, to be handed in before each week’s final class. Reaction papers might be one page, or five pages—it depends on you and your level of interest in the week’s reading. Important: these are not meant to be literature reviews; rather, you may think (in writing) about one or more of the focus questions, or, otherwise, consider any (relevant) topic that moves you, excites you, bothers, confuses, distracts, annoys, or otherwise touches you. Students should, at a minimum, be prepared to discuss each of that class period’s focus questions in conference. -

Linguistic Anthropology in 2013: Super-New-Big

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST Linguistic Anthropology Linguistic Anthropology in 2013: Super-New-Big Angela Reyes ABSTRACT In this essay, I discuss how linguistic anthropological scholarship in 2013 has been increasingly con- fronted by the concepts of “superdiversity,” “new media,” and “big data.” As the “super-new-big” purports to identify a contemporary moment in which we are witnessing unprecedented change, I interrogate the degree to which these concepts rely on assumptions about “reality” as natural state versus ideological production. I consider how the super-new-big invites us to scrutinize various reconceptualizations of diversity (is it super?), media (is it new?), and data (is it big?), leaving us to inevitably contemplate each concept’s implicitly invoked opposite: “regular diversity,” “old media,” and “small data.” In the section on “diversity,” I explore linguistic anthropological scholarship that examines how notions of difference continue to be entangled in projects of the nation-state, the market economy, and social inequality. In the sections on “media” and “data,” I consider how questions about what constitutes lin- guistic anthropological data and methodology are being raised and addressed by research that analyzes new and old technologies, ethnographic material, semiotic forms, scale, and ontology. I conclude by questioning the extent to which it is the super-new-big itself or the contemplation about the super-new-big that produces perceived change in the world. [linguistic anthropology, superdiversity, new media, big data, -

Skeeling 1.Pdf

Musicking Tradition in Place: Participation, Values, and Banks in Bamiléké Territory by Simon Robert Jo-Keeling A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Judith T. Irvine, Chair Emeritus Professor Judith O. Becker Professor Bruce Mannheim Associate Professor Kelly M. Askew © Simon Robert Jo-Keeling, 2011 acknowledgements Most of all, my thanks go to those residents of Cameroon who assisted with or parti- cipated in my research, especially Theophile Ematchoua, Theophile Issola Missé, Moise Kamndjo, Valerie Kamta, Majolie Kwamu Wandji, Josiane Mbakob, Georges Ngandjou, Antoine Ngoyou Tchouta, Francois Nkwilang, Epiphanie Nya, Basil, Brenda, Elizabeth, Julienne, Majolie, Moise, Pierre, Raisa, Rita, Tresor, Yonga, Le Comité d’Etudes et de la Production des Oeuvres Mèdûmbà and the real-life Association de Benskin and Associa- tion de Mangambeu. Most of all Cameroonians, I thank Emanuel Kamadjou, Alain Kamtchoua, Jules Tankeu and Elise, and Joseph Wansi Eyoumbi. I am grateful to the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research for fund- ing my field work. For support, guidance, inspiration, encouragement, and mentoring, I thank the mem- bers of my dissertation committee, Kelly Askew, Judith Becker, Judith Irvine, and Bruce Mannheim. The three members from the anthropology department supported me the whole way through my graduate training. I am especially grateful to my superb advisor, Judith Irvine, who worked very closely and skillfully with me, particularly during field work and writing up. Other people affiliated with the department of anthropology at the University of Michigan were especially helpful or supportive in a variety of ways. -

Ethnolinguistics in the Year 2016∗

Ethnolinguistic 28 Lublin 2017 I. Research articles DOI: 10.17951/et.2016.28.7 Jerzy B a r t m i ń s k i (UMCS, Lublin, Poland) Ethnolinguistics in the Year 2016∗ This article is the voice of Etnolingwistyka’s Editor-in-Chief on the current tasks of ethnolinguistics as a scholarly subdiscipline, as well as those of the journal. According to the author, of the two foundations of Slavic ethnolin- guistics mentioned by Nikita Tolstoy (i.e., its pan-Slavic character and the unity of language and culture) it is mainly the latter that has preserved its topicality: language is the source of knowledge about people and human com- munities, as well as the basis for building one’s identity (individual, national, regional, professional). The agenda of cultural linguistics has been followed by the contributors to the present journal and its editorial team with a focus on various genres of folklore, the problems of the linguistic worldview, and in recent issues with studies on the semantics of selected cultural concepts (FAMILY, DEMOCRACY, EQUALITY, OTVETSTVENNOST’, etc.). An ethnolinguistics that thus seeks “culture in language” (i.e. in the semantic layer of linguistic forms) is close – especially in its cognitivist variant – to Western cultural or anthropological linguistics. When Slavic ethnolinguistics focuses on the semantics of value terms, it stands a good chance of engaging in a dialogue with Western anthropological linguistics and contribute original insights to the common body of research on values. A specific proposal in this direction is the international project EUROJOS. Key words: cultural linguistics, culture in language, Etnolingwistyka, EUROJOS, Axiological Lexicon of Slavs and their Neighbours, cultural concepts ∗ This is a revised and extended version of the paper presented at the conference Slawische Ethnolinguistik: Methoden, Ergebnisse, Perspektive (17–19 December, 2015), organized by the Department of Slavonic Studies at the University of Vienna. -

White Noise: Bringing Language Into Whiteness Studies

Introduction ■ Sara Trechter CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, CHICO ■ Mary Bucholtz TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY White Noise: Bringing Language into Whiteness Studies Although the burgeoning field of whiteness studies encompasses a pan- oply of disciplines within the humanities and social sciences, including edu- cation (Fine et al. 1997), literary criticism (Morrison 1990), ethnic studies (Almaguer 1994; Lipsitz 1998), gender studies (Frankenberg 1993; Pfeil 1995), and history (Roediger 1991; Saxton 1990), it owes a special debt to anthro- pology. After all, the fundamental postulate of whiteness studies—that race is socially constructed—is based on extensive anthropological research ex- tending back to Boas and continuing to the present moment (e.g., Harrison 1995, 1998). Moreover, as a phenomenon grounded in what Hill (this issue) calls the “culture of racism,” the racial project of whiteness is especially suited to anthropological study. Indeed, anthropologists have been at the vanguard of scholarship in the critical investigation of whiteness. The in- fluential studies of such researchers as Karen Brodkin (1998) and John Hartigan (1999) have enriched the field by demonstrating the importance of historical, geographic, and ethnographic specificity in understanding the workings of whiteness. It is important to acknowledge, too, that these insights, which Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 11(1):3–21. Copyright © 2001, American Anthropological Association. 3 4 Journal of Linguistic Anthropology are currently getting renewed attention under the rubric of whiteness studies, have long been fundamental to the work of scholars of color in numerous disciplines, including anthropology. From W. E. B. Du Bois (1935) to James Baldwin (1985) to bell hooks (1990, 1992) and beyond, African Americans and other scholars of color recognized early on that race is a politicized social construction (see Roediger 1998 for an excellent compilation of such work). -

Chapter 2 Style

Chapter 2 Style "Every apparition can be experienced in two ways. The two ways are not at random, but they are attached to the apparitions – they are derived from the nature of the apparition, from two of their characteristics: exterior – interior.” Wassily Kandinsky1 “Le style c’est l’homme même.” Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon2 Although people find it difficult to define the concept of style spontaneously, they classify each other as belonging or not belonging together by respective styles. They always do so when they see others as punk, nerd, hipster, hippie, yuppie, emo, or belonging to hip hop or the mainstream. Which succeeds more fre- quently than not! Yet, the question is how this works and why. Sociology asserts style to be either representative or constitutive of social groups, or else both.3 However, there is consensus in all of sociology that social 1 Kandinsky 1973 (1926), p. 13, my translation. 2 Cited after Saisselin 1958. 3 Modernist sociology regards differences in endowment (financial and cultural capital) as being constitutive for forming social groups; style is merely representative of social groups (for exam- ple, the Birmingham School in its analysis of British youth cultures [Hebdige 1988]). In contrast, in the postmodern variant of sociology, the group style is understood as the constituent charac- teristic of the group; it is only by showing a style, that groups can come into being and are able to persist; other socio-cultural characteristics, for example the endowment with capital, play no or only a secondary role. Bourdieu (1982) marks the transition from modernism to postmodernism, 48 Part 1: Culture of Dissimiarity groups and their style form an inseparable entity. -

Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity Krystal A

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 1-1-2015 Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity Krystal A. Smalls University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the African American Studies Commons, Anthropological Linguistics and Sociolinguistics Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Smalls, Krystal A., "Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2022. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2022 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2022 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity Abstract From the colonization of the “Dark Continent,” to the global industry that turned black bodies into chattel, to the total absence of modern Africa from most American public school curricula, to superfluous representations of African primitivity in mainstream media, to the unflinching state-sanctioned murders of unarmed black people in the Americas, antiblackness and anti-black racism have been part and parcel to modernity, swathing centuries and continents, and seeping into the tiny spaces and moments that constitute social reality for most black-identified -

Introduction Reframing Framing: Interaction and the Constitution of Culture and Society

Pragmatics 21:2.185-190 2011 International Pragmatics Association DOI: 10.1075/prag.21.2.01par INTRODUCTION REFRAMING FRAMING: INTERACTION AND THE CONSTITUTION OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY Joseph Sung-Yul Park and Hiroko Takanashi Abstract This special issue revisits the notion of framing based on several recent developments in the fields of sociolinguistics, discourse analysis, and linguistic anthropology, particularly the current interest in the notions of stance, style, metalinguistics and language ideology. In doing so, the contributions highlight the importance of framing not only in the management of micro-level interactional practices but also in the reproduction of cultural ideologies and social relations. Keywords: Framing; Stance; Style; Language ideology; Interaction. This special issue aims to renew the interest in framing as a key concept for the analysis of interactional discourse. In particular, it highlights the role of framing in mediating the constitution of culture and social order in interactional contexts. Based on interactional data gathered from diverse contexts of Africa, Asia, and America, and building upon recent developments in the study of stance, style, and language ideology, the papers in this collection underline how speakers’ practices of framing can be understood as a locus for the dynamic reproduction of cultural assumptions and social organization. Goffman’s (1974, 1981) formulation of framing, based on Bateson’s (1972) work, has already had a major influence on how we understand the way participants in interaction intersubjectively negotiate and manage social meaning and social relations: that is, how they understand what is going on in the situation at hand, how they make sense of utterances produced, how they determine the positions they should take in relation to each other (Tannen and Wallat 1987).