Lake Leelanau Watershed Protection Plan Final Draft Approved 9-14-2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michigan Department of Natural Resources Fisheries Division

ATUR F N AL O R T E N S E O U M R T C R E A S STATE OF MICHIGAN P E DNR D M ICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES SR42 April 2007 The Fish Community and Fishery of Lake Leelanau, Leelanau County, Michigan with Emphasis on Walleyes, Northern Pike, and Smallmouth Bass Patrick A. Hanchin, Todd G. Kalish, Zhenming Su, and Richard D. Clark, Jr. ������������� ��������������������������� 0 1 2 3 Miles www.michigan.gov/dnr/ FISHERIES DIVISION SPECIAL REPORT 42 MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES FISHERIES DIVISION Fisheries Special Report 42 April 2007 The Fish Community and Fishery of Lake Leelanau, Leelanau County, Michigan with Emphasis on Walleyes, Northern Pike and Smallmouth Bass Patrick A. Hanchin, Todd G. Kalish, Zhenming Su, and Richard D. Clark, Jr. MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES (DNR) MISSION STATEMENT “The Michigan Department of Natural Resources is committed to the conservation, protection, management, use and enjoyment of the State’s natural resources for current and future generations.” NATURAL RESOURCES COMMISSION (NRC) STATEMENT The Natural Resources Commission, as the governing body for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, provides a strategic framework for the DNR to effectively manage your resources. The NRC holds monthly, public meetings throughout Michigan, working closely with its constituencies in establishing and improving natural resources management policy. MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES NON DISCRIMINATION STATEMENT The Michigan Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) provides equal opportunities for employment and access to Michigan’s natural resources. Both State and Federal laws prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, disability, age, sex, height, weight or marital status under the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 as amended (MI PA 453 and MI PA 220, Title V of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 as amended, and the Americans with Disabilities Act). -

Map of Natural and Preserves

The Leelanau Conservancy An Accredited Organization The Leelanau Conservancy was awarded accreditation status in September, 008. The Land Trust Accreditation Commission awards the accreditation seal to community institutions that meet national quality standards for protecting important natural places and working lands forever. Learn more at the Land Trust Alliance website: www.landtrustaccreditation.org. Map of Natural and Preserves Leelanau State Park and Open to the public Grand Traverse Light Best seen on a guided hike Lighthouse West Natural Area Finton Natural Area Critical areas, o limits Je Lamont Preserve Kehl Lake Natural Area North Soper Preserve Manitou Houdek Dunes M201 Island Natural Area NORTHPORT Gull Island Nedows Bay M 22 Preserve OMENA Belanger 637 Creek South Leland Village Green Preserve Manitou Whittlesey Lake MichiganIsland LELAND 641 Preserve Hall Beach North PESHAWBESTOWN Frazier-Freeland Manitou Passage Preserve Lake Leelanau M204 Whaleback Suttons Bay Sleeping Bear Dunes Natural Area 45th Parallel LAKE Park National Lakeshore LEELANAU SUTTONS Narrows 643 Natural Area GLEN Little M 22 BAY Crystal River HAVEN Traverse GLEN Lake Krumweide ARBOR 633 Forest 645 Reserve Little Big Greeno Preserve Glen Glen Lime Mebert Creek Preserve BINGHAM Teichner Lake Lake Lake 643 Preserve South M109 616 Lake Grand BURDICKVILLE MAPLE Leelanau Traverse CITY CEDAR 641 Chippewa Run Bay 669 651 M 22 Natural Area M 22 677 Cedar River 667 614 Cedar Sleeping Bear Dunes Lake Preserve Visitor's Center EMPIRE 616 DeYoung 651 616 Natural Area GREILICKVILLE M 72 Benzie County Grand Traverse County TRAVERSE CITY Conserving Leelanau’s Land, Water, and Scenic Character Who We Are We’re the group that, since 1988, has worked to protect the places that you love and the character that makes the Leelanau Peninsula so unique. -

Ultrasociality: When Institutions Make a Difference

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304625948 Ultrasociality: When institutions make a difference Article in Behavioral and Brain Sciences · June 2016 DOI: 10.1017/S0140525X15001089 CITATIONS READS 0 5 3 authors, including: Petr Houdek Julie Novakova Vysoká škola ekonomická v Praze Charles University in Prague 11 PUBLICATIONS 5 CITATIONS 6 PUBLICATIONS 9 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Petr Houdek Retrieved on: 20 September 2016 BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2016), Page 1 of 60 doi:10.1017/S0140525X1500059X, e92 The economic origins of ultrasociality John Gowdy Department of Economics and Department of Science and Technology Studies, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY 12180 [email protected] http://www.economics.rpi.edu/pl/people/john-gowdy Lisi Krall Department of Economics, State University of New York (SUNY) at Cortland, Cortland, NY 13045 [email protected] Abstract: Ultrasociality refers to the social organization of a few species, including humans and some social insects, having a complex division of labor, city-states, and an almost exclusive dependence on agriculture for subsistence. We argue that the driving forces in the evolution of these ultrasocial societies were economic. With the agricultural transition, species could directly produce their own food and this was such a competitive advantage that those species now dominate the planet. Once underway, this transition was propelled by the selection of within-species groups that could best capture the advantages of (1) actively managing the inputs to food production, (2) a more complex division of labor, and (3) increasing returns to larger scale and larger group size. -

Quantitative Appraisal of Non-Irrigated Cropland in South Dakota Shelby Riggs University of Nebraska - Lincoln

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Honors Program 10-22-2018 Quantitative Appraisal of Non-irrigated Cropland in South Dakota Shelby Riggs University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses Part of the Agribusiness Commons, Agricultural Economics Commons, Agricultural Science Commons, Applied Mathematics Commons, Applied Statistics Commons, and the Soil Science Commons Riggs, Shelby, "Quantitative Appraisal of Non-irrigated Cropland in South Dakota" (2018). Honors Theses, University of Nebraska- Lincoln. 117. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/117 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Quantitative Appraisal of Non-irrigated Ag Land in South Dakota An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the University Honors Program Requirements University of Nebraska – Lincoln By Shelby Riggs, BS Agricultural Economics College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources October 22nd, 2018 Faculty Mentor: Jeffrey Stokes, PhD, Agricultural Economics Abstract This appraisal attempts to remove subjectivity from the appraisal process and replace it with quantitative analysis of known data to generate fair market value the subject property. Two methods of appraisal will be used, the income approach and the sales comparison approach. For the income approach, I use the average cash rent for the region, the current property taxes for the subject property, and a capitalization rate based on Stokes’ (2018) capitalization rate formula to arrive at my income-based valuation. -

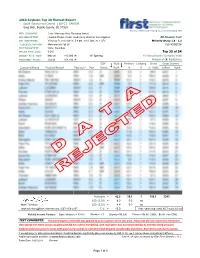

2018 Soybean Top 30 Harvest Report Top 30 of 54

2018 Soybean Top 30 Harvest Report South Dakota East Central [ SDEC ] CAVOUR Greg Bich, Beadle County, SD 57324 Test by: MNS Seed Testing, LLC, New Richland, MN PREV. CROP/HERB: Corn / Harness Xtra, Roundup (twice) SOIL DESCRIPTION: Houdek-Prosper loam, moderately drained, non-irrigated All-Season Test SOIL CONDITIONS: Very low P, very high K, 5.9 pH, 3.0% OM, 20.1 CEC Maturity Group 1.6 - 2.3 TILLAGE/CULTIVATION: Minimum w/o fall till S2018SDEC06 PEST MANAGEMENT: Valor, Roundup APPLIED N-P-K (units): 0-0-0 Top 30 of 54 SEEDED - RATE - ROW: May 26 140,000 /A 30" Spacing For Gross Income (Sorted by Yield) HARVESTED - STAND: Oct 23 108,100 /A Average of (2) Replications SCN Yield Moisture Lodging Stand Gross Income Company/Brand Product/Brand†Technol.† Mat. Resist. Bu/A % % (x 1000) $/Acre Rank Averages = 42.8 10.1 1 108.1 $343 LSD (0.10) = 8.3 0.5 ns Mark Tollefson LSD (0.25) = 4.4 0.3 ns [email protected], (507) 456-2357 C.V. = 15.0 Prev. years avg. yield, 45.7 bu/a, 10 yrs Yield & Income Factors: Base Moisture = 13.0% Shrink = 1.3 Drying = $0.020 Prices = $8.00 GMO; $8.00 non-GMO TEST COMMENTS: The preemergence herbicide was applied to only a portion of the test area. Areas that did not receive this treatment were weedy the entire season as glphosate did not control everything. One replication was not harvested due to extreme weed pressure. Soybean yield was great in areas with good weed control (1 replication) but dropped considerably elsewhere. -

Selected Qualitative Parameters Above-Ground Phytomass of the Lenor-First Slovak Cultivar of Festulolium A

Acta fytotechn zootechn, 22, 2019(1): 13–16 http://www.acta.fapz.uniag.sk Original Paper Selected qualitative parameters above-ground phytomass of the Lenor-first Slovak cultivar of Festulolium A. et Gr. Peter Hric*, Ľuboš Vozár, Peter Kovár Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra, Slovak Republic Article Details: Received: 2018-10-04 | Accepted: 2018-11-06 | Available online: 2019-01-31 https://doi.org/10.15414/afz.2019.22.01.13-16 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License The aim of this experiment was to compare selected qualitative parameters in above-ground phytomass of the first Slovak cultivar of Festulolium A et. Gr. cv. Lenor in comparison to earlier registered cultivars Felina and Hykor. The pot experiment was conducted at the Demonstrating and Research base of the Department of Grassland Ecosystems and Forage Crops, Slovak Agricultural University in Nitra (Slovak Republic) with controlled moisture conditions (shelter) in 2017. Content of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, crude fibre and water soluble carbohydrates were determined from dry above-ground phytomass of grasses. The significantly highest (P <0.05) nitrogen content in average of cuts was in above-ground phytomass of Felina (30.3 g kg-1) compared to Hykor (25.4 g kg-1) and new intergeneric hybrid Lenor (25.0 g kg-1). The lowest phosphorus content was found out in hybrid Lenor (3.4 g kg-1). In average of three cuts, the lowest concentration of potassium was in new intergeneric hybrid Lenor (5.8 g kg-1). The lowest content of calcium was found out in hybrid Lenor (7.0 g kg-1). -

Brochure No Bleed

trailo BEST N WINE 2 REGION guide by USA TODAY HELLO FRIENDS OF DOWNLOAD THE NORTHERN MICHIGAN! LEELANAU PENINSULA The Leelanau Peninsula Wine Trail is open for WINE TRAIL APP! business and we are excited to see you soon. The Leelanau Peninsula Wine Trail App will connect As we continue to operate with the safety of you with Michigan's oldest and largest wine trail. Get our guests and our teams as the number one maps and details for great wine destinations and be priority, we must evaluate each event we host among the first to know about promotions, discounts, based on that criteria and within the mandates ticket giveaways and fun prizes. handed down by the Governor's office and Michigan HHS. Because of this, we are making decisions on our event plans for the remainder of 2020 and through the spring of 2021 on a case-by-case basis. We were very excited to host successful events this fall in a format that allows for safe and meaningful engagement with our wineries and it is our hope to continue to do so in the months to come. Please refer to www.lpwines.com for current and up-to-date information and details about what the Leelanau Peninsula Wine Trail is offering. We also encourage you to visit the individual websites of the wineries along our trail when planning your visit to best understand what protocols and procedures may be in place in each unique tasting room. While we work together, we would like to thank you for your continued support and we look forward to seeing you along the trail! Rick DeBlasio, President Cover photo credit: -

Comprehensive Conservation Plan, Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex, South Dakota

Comprehensive Conservation Plan Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex South Dakota December 2012 Approved by Noreen Walsh, Regional Director Date U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6 Lakewood, Colorado Prepared by Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex 38672 291st Street Lake Andes, South Dakota 57356 605 /487 7603 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 6, Mountain–Prairie Region Division of Refuge Planning 134 Union Boulevard, Suite 300 Lakewood, Colorado 80228 303 /236 8145 CITATION for this document: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Comprehensive Conservation Plan, Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex, South Dakota. Lakewood, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 218 p. Comprehensive Conservation Plan Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex South Dakota Submitted by Concurred with by Michael J. Bryant Date Bernie Peterson. Date Project Leader Refuge Supervisor, Region 6 Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Lake Andes, South Dakota Lakewood, Colorado Matt Hogan Date Assistant Regional Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6 National Wildlife Refuge System Lakewood, Colorado Contents Summary ....................................................................................................................................... XI Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................. XVII CHAPTER 1–Introduction ..................................................................... -

2019 FIRST Harvest Report

SCN Yield Moisture Lodging Stand Gross Income Company/Brand Product/Brand Technol.† RM Resist. Bu/A % % (x 1000) $/Acre Rank HEFTY H24X8 RRX 2.4 MR 58.2 15.0 1 114.2 492 1 ASGROW AG22X0 § RRX 2.2 R 57.4 14.2 6 112.3 486 2 Test by: MNS Seed Testing, LLC New Richland, MN TITAN PRO 28E8 E3 2.8 R 55.8 14.4 5 112.3 472 3 2019 Soybeans Top 30 Harvest Report HOEGEMEYER 2540 E E3 2.5 R 55.2 14.4 2 113.3 467 4 South Dakota Southeast [SDSE] SALEM, SD REA RX2518 § RRX 2.5 R 54.9 14.5 4 110.4 465 5 Ernie Christensen, McCook County, SD 57048 HOEGEMEYER 2202 NX RRX 2.2 R 54.5 14.3 4 113.3 461 6 All-Season Test 2.1 - 2.8 Day CRM REA RX2639 GC RRX 2.6 R 53.8 14.1 7 114.7 456 7 S2019SDSE04 GENESIS G2140E E3 2.1 R 53.4 14.1 5 112.3 452 8 For Gross Income Top 30 of 54 CREDENZ CZ 2550GTLL LG27 2.5 MR 53.4 14.1 2 110.4 452 9 (Sorted by Yield) Average of (3) Replications LATHAM L 2549R2X RRX 2.5 R 53.1 14.1 2 112.3 450 10 CHAMPION 25X70N RRX 2.5 R 52.9 14.2 2 111.4 448 11 PREV. CROP/HERB: Corn / Valor, Roundup GENESIS G2181GL LG27 2.2 R 52.6 14.5 1 107.4 445 12 SOIL DESCRIPTION: Houdek-Prosper loam, moderately drained, non- NK BRAND S20-J5X § RRX 2.0 R 52.4 13.9 14 108.4 444 13 irrigated HEFTY Z2300E E3 2.3 R 52.3 13.8 2 112.3 444 14 SOIL CONDITION: very high P, very high K, 5.9 NK BRAND S21-W8X § RRX 2.1 R 52.2 14.0 5 109.4 442 15 pH, 3.0% OM, 19.3 CEC STINE 25GA62 § LG27 2.5 R 52.0 14.0 2 111.3 441 16 TILLAGE/CULTIVATION: Conventional W/ Fall Till PIONEER P21A28X § RRX 2.1 R 51.7 14.1 2 105.5 438 17 PEST MANAGEMENT: Valor, Roundup, Select Max HOEGEMEYER 2820 E E3 2.8 R 51.4 15.1 5 112.3 434 18 Applied N-P-K (units): 0-0-0 HEFTY Z2700E E3 2.7 R 51.3 14.7 1 113.3 434 19 SEEDED - RATE - ROW: Jun 12 140.0 /A 30" spacing LATHAM L 2395 LLGT27 LG27 2.3 R 51.2 14.0 5 108.4 434 20 HARVESTED - STAND: Nov 1 111.4 /A DYNA-GRO S24XT08 RRX 2.4 R 51.2 15.1 2 113.3 433 22 RENK RS248NX RRX 2.4 R 51.2 15.5 2 112.3 432 23 TEST COMMENTS: RENK RS250NX RRX 2.5 R 51.2 14.1 1 112.3 434 21 This was a clean field with a fairly consistent stand of HEFTY H25X0 RRX 2.5 R 50.9 14.3 2 113.3 431 24 soybeans. -

Management Plan 2011.Pub

Leelanau Scenic Heritage Route Corridor Management Plan Update 2012 Leelanau Scenic Heritage Route Committee Committee Members Jack Kelly, Elmwood Township Doug Hill, Bingham Township Tom Nixon, Suttons Bay Township Wally Delamater, Village of Suttons Bay Erik Zehender, Lake Leelanau Community Marsha Buehler, Leelanau Township Phil Mikesell, Village of Northport Leland Township Centerville Township Tim Stein Cleveland Township Sharon Oriel, Glen Arbor Township Jill Webb, Empire Township Linda Payment, Village of Empire Robert Kalbfleisch, Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians Greg Julian, Leelanau County Planning Commission Charles Godbout, Leelanau County Planning Commission Lee Bowen, Leelanau County Road Commission Kimberly Mann, Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore Lois Bahle, Suttons Bay Chamber of Commerce Yarrow Wolfe, Leelanau Conservancy Leonard Marzalek, Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes Becky Thatcher, Leland Merchants Lee Maynard, TART Trails Inc. Joanie Woods, Citizen Michigan Department of Transportation Gary Niemi, Transportation Service Center, Traverse City Dave Langhorst, North Region Office Northwest Michigan Council of Governments Committee coordination, staffing and administrative support This Corridor Management Plan is Presented by: The Leelanau Scenic Heritage Route Committee, Leelanau County, Michigan www.nwm.org/lshr.asp Prepared by: Northwest Michigan Council of Governments Northwest Michigan Council of Governments. PO Box 506, Traverse City, Michigan 49685-0506. www.nwm.org The Northwest Michigan Council of Governments provides regional planning, economic development, and workforce development services to its ten member counties of Antrim, Benzie, Charlevoix, Emmet, Grand Traverse, Kalkaska, Leelanau, Manistee, Missaukee, and Wexford. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page # I. Executive Summary 5 II. Corridor Management Update 6 A. Introduction B. Corridor Inventory 1. -

2020 South Dakota Soybean Variety Trial Results

South Dakota Agricultural agronomy Experiment Station at SDSU SOUTH DAKOTA STATE UNIVERSITY® OCTOBER 2020 AGRONOMY, HORTICULTURE, & PLANT SCIENCE DEPARTMENT 2020 South Dakota Soybean Variety Trial Results Plankinton Jonathan Kleinjan | SDSU Extension Crop Production Associate Kevin Kirby | Agricultural Research Manager Shawn Hawks | Agricultural Research Manager Location: 6 miles north and 4 miles west of Plankinton (57368) in Aurora County, SD (GPS: 43.802972° -98.556917°) Cooperator: Edinger Brothers Soil Type: Houdek-Dudley complex, 0-2% slopes Fertilizer: none Previous crop: corn Tillage: minimum-till Row spacing: 30 inches Seeding Rate: 150,000/acre Herbicide: Pre: 3 oz/acre Fierce (flumioxazin + pyroxasulfone) + 5 oz/acre Metribuzin (metribuzin) + 3.3 pt/acre Prowl H2O (pendimethalin) Post: none Insecticide: none Date seeded: 6/2/2020 Date harvested: 10/16/2020 SDSU Extension is an equal opportunity provider and employer in accordance with the nondiscrimination policies of South Dakota State University, the South Dakota Board of Regents and the United States Department of Agriculture. Learn more at extension.sdstate.edu. S-0002-06 2020 South Dakota Soybean Variety Trial Results Plankinton Table 1. Glyphosate-resistant soybean variety performance results (average of 4 replications - Maturity Group 1 at Plankinton, SD. Variety Information Agronomic Performance Maturity Yield Lodging Score Brand Variety Moisture (%) Rating (bu/ac@13%) (1-5)* LG Seeds C1838RX 1.8 62.8 9.2 1.0 P3 Genetics 2117E 1.7 60.3 9.1 1.0 Peterson Farms Seed 21X16N 1.6 59.8 9.3 1.0 LG Seeds LGS1776RX 1.7 58.4 9.3 1.0 Farmer Check 1 1818R2X 1.8 58.0 9.2 1.0 Farmer Check 2 P19A14X 1.9 57.9 8.8 1.0 Check 14X0 1.4 54.9 9.0 1.0 Trial Average 58.9 9.1 1.0 LSD (0.05)† 3.3 0.4 - C.V.‡ 3.8 3.1 - *Lodging Score (1 = no lodging to 5 = flat on the ground). -

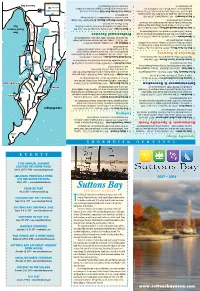

Suttonsbayarea.Com

www.suttonsbayarea.com historic village by “slowing down” just a bit. a just down” “slowing by village historic ELIZABETH HAYDEN|EHGRAPHICDESIGN January 27 2018– www.suttonsbayarea.com 2018– 27 January century architecture intact. We hope that you will savor the charms of this this of charms the savor will you that hope We intact. architecture century FEST YETI anymore, but on St. Joseph Street, our main street, with much of its 19th 19th its of much with street, main our Street, Joseph St. on but anymore, up highway M-22, you will suddenly find that you are not on a state highway highway state a on not are you that find suddenly will you M-22, highway up or a parking meter. In some ways little has changed. Today, when you travel travel you when Today, changed. has little ways some In meter. parking a or December 2 & 3, 2017– www.suttonsbayarea.com 2017– 3, & 2 December In our village there are no fast food franchises, nor is there a stoplight stoplight a there is nor franchises, food fast no are there village our In VILLAGE THE IN HOLIDAY short drive away. drive short boating, cross country skiing, casino gaming, and two national parks – all a a all – parks national two and gaming, casino skiing, country cross boating, November 25, 2017 – www.suttonsbayarea.com – 2017 25, November The Leelanau Peninsula offers wineries, golf, sport fishing, Great Lakes Lakes Great fishing, sport golf, wineries, offers Peninsula Leelanau The SATURDAY BUSINESS SMALL beautiful nature walk along the bay. the along walk nature beautiful side of the Marina.