Public Order, Crime and Punishment in Istanbul, 1914-1918

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix F Ottoman Casualties

ORDERED TO DIE Recent Titles in Contributions in Military Studies Jerome Bonaparte: The War Years, 1800-1815 Glenn J. Lamar Toward a Revolution in Military Affairs9: Defense and Security at the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century Thierry Gongora and Harald von RiekhojJ, editors Rolling the Iron Dice: Historical Analogies and Decisions to Use Military Force in Regional Contingencies Scot Macdonald To Acknowledge a War: The Korean War in American Memory Paid M. Edwards Implosion: Downsizing the U.S. Military, 1987-2015 Bart Brasher From Ice-Breaker to Missile Boat: The Evolution of Israel's Naval Strategy Mo she Tzalel Creating an American Lake: United States Imperialism and Strategic Security in the Pacific Basin, 1945-1947 Hal M. Friedman Native vs. Settler: Ethnic Conflict in Israel/Palestine, Northern Ireland, and South Africa Thomas G. Mitchell Battling for Bombers: The U.S. Air Force Fights for Its Modern Strategic Aircraft Programs Frank P. Donnini The Formative Influences, Theones, and Campaigns of the Archduke Carl of Austria Lee Eystnrlid Great Captains of Antiquity Richard A. Gabriel Doctrine Under Trial: American Artillery Employment in World War I Mark E. Grotelueschen ORDERED TO DIE A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War Edward J. Erickson Foreword by General Huseyin Kivrikoglu Contributions in Military Studies, Number 201 GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Erickson, Edward J., 1950— Ordered to die : a history of the Ottoman army in the first World War / Edward J. Erickson, foreword by General Htiseyin Kivrikoglu p. cm.—(Contributions in military studies, ISSN 0883-6884 ; no. -

The Political Ideas of Derviş Vahdeti As Reflected in Volkan Newspaper (1908-1909)

THE POLITICAL IDEAS OF DERVİŞ VAHDETİ AS REFLECTED IN VOLKAN NEWSPAPER (1908-1909) by TALHA MURAT Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabancı University AUGUST 2020 THE POLITICAL IDEAS OF DERVİŞ VAHDETİ AS REFLECTED IN VOLKAN NEWSPAPER (1908-1909) Approved by: Assoc. Prof. Selçuk Akşin Somel . (Thesis Supervisor) Assist. Prof. Ayşe Ozil . Assist. Prof. Fatih Bayram . Date of Approval: August 10, 2020 TALHA MURAT 2020 c All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT THE POLITICAL IDEAS OF DERVİŞ VAHDETİ AS REFLECTED IN VOLKAN NEWSPAPER (1908-1909) TALHA MURAT TURKISH STUDIES M.A. THESIS, AUGUST 2020 Thesis Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Selçuk Akşin Somel Keywords: Derviş Vahdeti, Volkan, Pan-Islamism, Ottomanism, Political Islam The aim of this study is to reveal and explore the political ideas of Derviş Vahdeti (1870-1909) who was an important and controversial actor during the first months of the Second Constitutional Period (1908-1918). Starting from 11 December 1908, Vahdeti edited a daily newspaper, named Volkan (Volcano), until 20 April 1909. He personally published a number of writings in Volkan, and expressed his ideas on multiple subjects ranging from politics to the social life in the Ottoman Empire. His harsh criticism that targeted the policies of the Ottoman Committee of Progress and Union (CUP, Osmanlı İttihâd ve Terakki Cemiyeti) made him a serious threat for the authority of the CUP. Vahdeti later established an activist and religion- oriented party, named Muhammadan Union (İttihâd-ı Muhammedi). Although he was subject to a number of studies on the Second Constitutional Period due to his alleged role in the 31 March Incident of 1909, his ideas were mostly ignored and/or he was labelled as a religious extremist (mürteci). -

© 2008 Hyeong-Jong

© 2011 Elise Soyun Ahn SEEING TURKISH STATE FORMATION PROCESSES: MAPPING LANGUAGE AND EDUCATION CENSUS DATA BY ELISE SOYUN AHN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Policy Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2011 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Pradeep Dhillon, Chair Professor Douglas Kibbee Professor Fazal Rizvi Professor Thomas Schwandt Abstract Language provides an interesting lens to look at state-building processes because of its cross- cutting nature. For example, in addition to its symbolic value and appeal, a national language has other roles in the process, including: (a) becoming the primary medium of communication which permits the nation to function efficiently in its political and economic life, (b) promoting social cohesion, allowing the nation to develop a common culture, and (c) forming a primordial basis for self-determination. Moreover, because of its cross-cutting nature, language interventions are rarely isolated activities. Languages are adopted by speakers, taking root in and spreading between communities because they are legitimated by legislation, and then reproduced through institutions like the education and military systems. Pádraig Ó’ Riagáin (1997) makes a case for this observing that ―Language policy is formulated, implemented, and accomplishes its results within a complex interrelated set of economic, social, and political processes which include, inter alia, the operation of other non-language state policies‖ (p. 45). In the Turkish case, its foundational role in the formation of the Turkish nation-state but its linkages to human rights issues raises interesting issues about how socio-cultural practices become reproduced through institutional infrastructure formation. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

Download Download

British Journal for Military History Volume 7, Issue 1, March 2021 What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915-1918 Roslyn Shepherd King Pike ISSN: 2057-0422 Date of Publication: 19 March 2021 Citation: Roslyn Shepherd King Pike, ‘What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915-1918’, British Journal for Military History, 7.1 (2021), pp. 87-112. www.bjmh.org.uk This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The BJMH is produced with the support of IDENTIFYING MILITARY ENGAGEMENTS IN EGYPT & THE LEVANT 1915-1918 What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915- 1918 Roslyn Shepherd King Pike* Independent Scholar Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This article examines the official names listed in the 'Egypt and Palestine' section of the 1922 report by the British Army’s Battles Nomenclature Committee and compares them with descriptions of military engagements in the Official History to establish if they clearly identify the events. The Committee’s application of their own definitions and guidelines during the process of naming these conflicts is evaluated together with examples of more recent usages in selected secondary sources. The articles concludes that the Committee’s failure to accurately identify the events of this campaign have had a negative impacted on subsequent historiography. Introduction While the perennial rose would still smell the same if called a lily, any discussion of military engagements relies on accurate and generally agreed on enduring names, so historians, veterans, and the wider community, can talk with some degree of confidence about particular events, and they can be meaningfully written into history. -

The Story of the Life and Times of Thomas Cosmades

Thomas Cosmades The Story of the Life and Times of Thomas Cosmades Introduction For years friends and family have been requesting me to put down at least the highlights of my life, pleasant and unpleasant. Following serious thought I concluded that doing this could be of service to people dear to me. Also my account can benefit coming generations. Many recollections in my thoughts still cheer my heart and others sadden, or make me ashamed, even after many years. If I fail to put my remembrances on paper they will die with me; otherwise they will profit those interested. I am confident of their being useful, at least to some. Innumerable people have written and published their life stories. Some have attracted favorable impressions and others the contrary. The free pen entrusted for free expression shouldn’t hesitate to record memories of some value. We are living in an age of intimidation and trepidation. People everywhere are weighing their words, writings, criticisms, drawings, etc. Prevailing conditions often dictate people’s manner of communication. Much talk is going around regarding democracy and free speech. Let’s be candid about it, democratic freedom is curtailed at every turn with the erosion of unrestricted utterance. The free person shouldn’t be intimidated by exorbitant reaction, or even violence. I firmly believe that thoughts, events and injustices should be spelled out. Therefore, I have recorded these pages. I did not conceal my failures, unwise decisions and crises in my own life. The same principle I have applied to conditions under which I lived and encountered from my childhood onwards. -

A REASSESSMENT: the YOUNG TURKS, THEIR POLITICS and ANTI-COLONIAL STRUGGLE the Jeunes Turcs Or Young Turks Were a Heterogeneous

DOĞU ERGIL A REASSESSMENT: THE YOUNG TURKS, THEIR POLITICS AND ANTI-COLONIAL STRUGGLE INTRODUCTION The Jeunes Turcs or Young Turks were a heterogeneous body of in tellectuals with conflicting interests and ideologies. However, their common goal was opposition to Hamidian absolutism. Although the Young Turks were the heirs of the New Ottoman political tradition of constitutionalism and freedom —which were believed to be the final words in modernization by both factions— they did not come from the elite bureaucratic circles of the New Ottomans1. The Young Turks were the products of the modern secular, military or civilian professional schools. They «belonged to the newly emerging professional classes: lecturers in the recently founded government colleges, lawyers trained in western law, journalists, minor clerks in the bureaucracy, and junior officers trained in western-style war colleges. Most of them were half-educated and products of the state (high) schools. The well-educated ones had no experience of administration and little idea about running a government. There was not a single ex perienced statesman amongst them»12. The historical evidence at hand suggests that the great majority of the Young Turk cadres was recruited primarily from among the children of the petty-bourgeoisie. Most of the prominent Young Turk statesmen came from such marginal middle-class families. For example, Talat Paşa (Prime Minister) was a small postal clerk in Salonica with only a junior high-school education 1. The best socio-historical account of the -

Fall 1958 SOCIALIST Volume 19 No.4 REVIEW

Another Step Ahead Deserved Praise The United Independent-Socialist porty Barring legal tricks which either the ever, has endorsed virtually all the ticket in New York deserves proise for mok ing a clean break with the Communist porty Republican or Democratic machines Democratic candidates, including Hogan that all might attempt in a last-ditch effort to for senator. Hogan is such an abject ond rejecting the latter's proposal condidates except Corliss Lamont for U.S. maintain their monopoly of the voting creature of the De Sapio machine that booths, the United . Independent-So even the millionaire Harriman sought Senate withdraw as the price of CP support. Such support would in any cIISe be a ruin cialist ticket was assured of its place to block his nomination. ous incubus. The Worker, the porty's weekly on the New York ballot as we went to The capacity of the Social Democratic press. orgon, hos sunk into the most deadly slovish and Communist party leaders to unite ness to Muscovite line, os wos evident ogoin The success in getting sufficient sig against a socialist ticket and in favor (Aug. 17) in its criticism of John T. Mc natures on the nominating petitions was of "lesser evil" candidates of one of the Monus, the U.I.S. candidate for Governor, a signal achievement, for besides the two capitalist machines should prove in because the National Guardi~n of which he unreasonable technical requirements, the structive to members of both organiza is editor criticized the execution of Nagy arduous work was hampered by ambush tions. -

Faculty of Humanities

FACULTY OF HUMANITIES The Faculty of Humanities was founded in 1993 due to the restoration with the provision of law legal decision numbered 496. It is the first faculty of the country with the name of The Faculty of Humanities after 1982. The Faculty started its education with the departments of History, Sociology, Art History and Classical Archaeology. In the first two years it provided education to extern and intern students. In the academic year of 1998-1999, the Department of Art History and Archaeology were divided into two separate departments as Department of Art History and Department of Archaeology. Then, the Department of Turkish Language and Literature was founded in the academic year of 1999-2000 , the Department of Philosophy was founded in the academic year of 2007-2008 and the Department of Russian Language and Literature was founded in the academic year of 2010- 2011. English prep school is optional for all our departments. Our faculty had been established on 5962 m2 area and serving in a building which is supplied with new and technological equipments in Yunusemre Campus. In our departments many research enhancement projects and Archaeology and Art History excavations that students take place are carried on which are supported by TÜBİTAK, University Searching Fund and Ministry of Culture. Dean : Vice Dean : Prof. Dr. Feriştah ALANYALI Vice Dean : Assoc. Prof. Dr. Erkan İZNİK Secretary of Faculty : Murat TÜRKYILMAZ STAFF Professors: Feriştah ALANYALI, H. Sabri ALANYALI, Erol ALTINSAPAN, Muzaffer DOĞAN, İhsan GÜNEŞ, Bilhan -

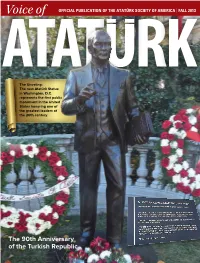

The 90Th Anniversary of the Turkish Republic CHAIRMAN’S COMMENTS the Atatürk Society of America Voice of 4731 Massachusetts Ave

Voice of OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE ATATÜRK SOCIETY OF AMERICA | FALL 2013 The Unveling: The new Atatürk Statue in Washington, D.C. represents the first public monument in the United States honoring one of the greatest leaders of the 20th century. The 90th Anniversary of the Turkish Republic CHAIRMAN’S COMMENTS The Atatürk Society of America Voice of 4731 Massachusetts Ave. NW CONTENTS Washington DC 20016 Phone 202 362 7173 Fax 202 363 4075 Mustafa Kemal’in Askerleriyiz... CHAIRMAN’S COMMENTS E-mail [email protected] 03 www.Ataturksociety.org Reversal of the Atatürk miracle— We are the soldiers of Mustafa Kemal... Destruction of Secular Democracy EXECUTIVE BOARD “There are two Mustafa Kemals. One, the flesh-and-blood Mustafa Kemal who now stands before Hudai Yavalar you and who will pass away. The other is you, all of you here who will go to the far corners of our President land to spread the ideals which must be defended with your lives if necessary. I stand for the nation's Prof. Bülent Atalay PRESIDENT’S COMMENTS dreams, and my life's work is to make them come true.” 04 Vice President —Mustafa Kemal Atatürk 10th of November — A day to Mourn Filiz Odabas-Geldiay Dr. Bulent Atalay Treasurer Members Believing secularism , democracy, science and technology Mirat Yavalar Aynur Uluatam Sumer 06 he year 2013 marked the 90th anniversary of the founding of the Turkish Republic. And ASA NEWS Secretary Ilknur Boray Hudai Yavalar 05 it was also the year of the most significant uprising in the history of Turkey. The chant Lecture by Dr. -

THE GREAT WAR and the TRAGEDY of ANATOLIA ATATURK SUPREME COUNCIL for CULTURE, LANGUAGE and HISTORY PUBLICATIONS of TURKISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY Serial XVI - No

THE GREAT WAR AND THE TRAGEDY OF ANATOLIA ATATURK SUPREME COUNCIL FOR CULTURE, LANGUAGE AND HISTORY PUBLICATIONS OF TURKISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY Serial XVI - No. 88 THE GREAT WAR AND THE TRAGEDY OF ANATOLIA (TURKS AND ARMENIANS IN THE MAELSTROM OF MAJOR POWERS) SALAHi SONYEL TURKISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRINTING HOUSE - ANKARA 2000 CONTENTS Sonyel, Salahi Abbreviations....................................................................................................................... VII The great war and the tragedy of Anatolia (Turks and Note on the Turkish Alphabet and Names.................................................................. VIII Armenians in the maelstrom of major powers) / Salahi Son Preface.................................................................................................................................... IX yel.- Ankara: Turkish Historical Society, 2000. x, 221s.; 24cm.~( Atattirk Supreme Council for Culture, Introduction.............................................................................................................................1 Language and History Publications of Turkish Historical Chapter 1 - Genesis of the 'Eastern Q uestion'................................................................ 14 Society; Serial VII - No. 189) Turco- Russian war of 1877-78......................................................................... 14 Bibliyografya ve indeks var. The Congress of B erlin....................................................................................... 17 ISBN 975 - 16 -

Who's Who in Politics in Turkey

WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS IN TURKEY Sarıdemir Mah. Ragıp Gümüşpala Cad. No: 10 34134 Eminönü/İstanbul Tel: (0212) 522 02 02 - Faks: (0212) 513 54 00 www.tarihvakfi.org.tr - [email protected] © Tarih Vakfı Yayınları, 2019 WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS IN TURKEY PROJECT Project Coordinators İsmet Akça, Barış Alp Özden Editors İsmet Akça, Barış Alp Özden Authors Süreyya Algül, Aslı Aydemir, Gökhan Demir, Ali Yalçın Göymen, Erhan Keleşoğlu, Canan Özbey, Baran Alp Uncu Translation Bilge Güler Proofreading in English Mark David Wyers Book Design Aşkın Yücel Seçkin Cover Design Aşkın Yücel Seçkin Printing Yıkılmazlar Basın Yayın Prom. ve Kağıt San. Tic. Ltd. Şti. Evren Mahallesi, Gülbahar Cd. 62/C, 34212 Bağcılar/İstanbull Tel: (0212) 630 64 73 Registered Publisher: 12102 Registered Printer: 11965 First Edition: İstanbul, 2019 ISBN Who’s Who in Politics in Turkey Project has been carried out with the coordination by the History Foundation and the contribution of Heinrich Böll Foundation Turkey Representation. WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS IN TURKEY —EDITORS İSMET AKÇA - BARIŞ ALP ÖZDEN AUTHORS SÜREYYA ALGÜL - ASLI AYDEMİR - GÖKHAN DEMİR ALİ YALÇIN GÖYMEN - ERHAN KELEŞOĞLU CANAN ÖZBEY - BARAN ALP UNCU TARİH VAKFI YAYINLARI Table of Contents i Foreword 1 Abdi İpekçi 3 Abdülkadir Aksu 6 Abdullah Çatlı 8 Abdullah Gül 11 Abdullah Öcalan 14 Abdüllatif Şener 16 Adnan Menderes 19 Ahmet Altan 21 Ahmet Davutoğlu 24 Ahmet Necdet Sezer 26 Ahmet Şık 28 Ahmet Taner Kışlalı 30 Ahmet Türk 32 Akın Birdal 34 Alaattin Çakıcı 36 Ali Babacan 38 Alparslan Türkeş 41 Arzu Çerkezoğlu