Lythological Features and Stonemasonry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CPCCST3003A Split Stone Manually

CPCCST3003A Split stone manually Release: 1 CPCCST3003A Split stone manually Date this document was generated: 26 May 2012 CPCCST3003A Split stone manually Modification History Not Applicable Unit Descriptor Unit descriptor This unit specifies the outcomes required to split stone using a range of methods for both hard and soft stone. Application of the Unit Application of the unit This unit of competency supports the achievement of skills and knowledge to split stone manually, which may include working with others and as a member of a team. Licensing/Regulatory Information Not Applicable Pre-Requisites Prerequisite units CPCCOHS2001A Apply OHS requirements, policies and procedures in the construction industry Approved Page 2 of 11 © Commonwealth of Australia, 2012 Construction & Property Services Industry Skills Council CPCCST3003A Split stone manually Date this document was generated: 26 May 2012 Employability Skills Information Employability skills This unit contains employability skills. Elements and Performance Criteria Pre-Content Elements describe the Performance criteria describe the performance needed to essential outcomes of a demonstrate achievement of the element. Where bold unit of competency. italicised text is used, further information is detailed in the required skills and knowledge section and the range statement. Assessment of performance is to be consistent with the evidence guide. Approved Page 3 of 11 © Commonwealth of Australia, 2012 Construction & Property Services Industry Skills Council CPCCST3003A Split stone manually Date this document was generated: 26 May 2012 Elements and Performance Criteria ELEMENT PERFORMANCE CRITERIA 1. Plan and prepare. 1.1. Work instructions and operational details are obtained using relevant information, confirmed and applied for planning and preparation purposes. -

Building the Lighthouse on Montague

SELF-GUIDED TOUR 2 BUILDING THE LIGHT This self-guided tour focuses on the construction of the Lighthouse on Montague Island - in particular the work of the stonemasons. PERHAPS BEGIN THIS TOUR SITTING ON THE STEPS LEADING UP TO THE TOWER... LOOK... at the tower: • Observe how it “grows” from the rock... • Appreciate its proportions suggesting strength, durability and watchfulness. • Notice the courses of blocks, the windows, the overhangs, the balcony and the lantern room at the top. CONSIDER... This Lighthouse has been operating continuously since 1881 - staffed until September 1986, and then automatically since 1986. The Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) now maintains the tower and light, totally funded by the shipping and insurance industries. GUIDE TO YOUR TOUR SIGNIFICANT DATES: 1873 Decision for a “First Order, Fixed and Flashing Light” on Montague Island 1877 Monies allocated within NSW budget – James Barnet, Colonial Architect, designs the lighthouse and buildings. 1878 – October Tenders let – Musson and Co wins the tender. 1879 – June? Musson surrenders his contract 1880 – July Fresh tenders called – William H. Jennings of Sydney wins the tender. 1880 – September Visitors impressed with Jennings’ Progress. 1881 – October Work completed by Jennings, 4 months ahead of schedule. 1881 – November 1st Lighthouse is formally opened by the NSW Marine Board THE DESIGN OF THE LIGHT STATION AND TOWER. James Barnet, the Colonial Architect from 1865 to 1890, was responsible for some 15 lighthouses in NSW, in particular during the period 1875-1885. Other lighthouses he designed include the Macquarie Light on Sydney’s south head, after Greenway’s tower experienced problems; Cape Byron; Norah Head; and the nearby Greencape light, south of Eden. -

Stillwater Stoneworks Las Vegas Fabricator & Sculptor Approaches Stone from a Different Angle TEVE Hitman Does Not by Stacy B

www.slipperyrockgazette.net VOLUME 19, ISSUE 231 THE BEACON OF THE STONE INDUSTRY OCTOBER 2013 Stillwater Stoneworks LAS VEGAS FABRICATOR & SCULPTOR APPROACHES STONE FROM A DIffERENT ANGLE TEVE Hitman does not by Stacy B. Williams like to call himself an artist, because he says Photos by Johnny Vizina not all art has to be functional. But the man with the philosophy behind Stillwater Stonework maintains a fluid bal- ance of artistry, functionality and crafts- manship in his finished products. He just approaches things from a different angle. His stone furniture and home accent pieces are one-of-a-kind creative, and his philoso- phy comes from a deep reservoir of passion, ambition and, well, water. He grew up on the New Jersey coast and water has always been the source of influence and inspiration in his stonework. Hitman has been sculpting since he was a boy and made his first surfboard at age 10. “There is constant movement in water,” Above: 3-tiered round patio table, 42˝ diameter. Hitman says, and he seeks to activate some Stone: 3cm Giallo Antigua on a steel-threaded of that movement with the stone he uses and reinforced ceramic pillar. in the sculptures he makes. Left: Kitchen counters and coordinating cladding Each project is approached with innovation from a honey-colored slab of Giallo Antigua. and fluidity according to the client’s desires Backsplash is coordinated Ivory and Noche trav- and space. Whether he is installing a white ertine. Note the matching cake stand made from a column of Giallo with Black Granite base and top. -

Siege Machines Will Spare No Effort to Storm the Town and Its Defenders

RULEBOOK (WORK IN PROGRESS) 1 THE CONVICTED INTRODUCTION The Convicted is a cooperative board game for 1-4 players. In The Convicted players become convicts who were given a second chance to expiate their crimes. In order to prove their true de- votion for the ruler, they need to colonize new lands in the name of the king. They start building their headquarters – town – with just a handful of footman, and a few structures. Through the development of fortifi cations, buildings, researching new technolo- gies, gathering resources and training recruits they can transform their colony into an impenetrable fortress. Alas, the new world is full of indigenous inhabitants who by any means possible try to get rid of unwanted colonizers. Countless hordes of barbarians, forest people, ferocious monsters and wolf men with their beasts and siege machines will spare no effort to storm the town and its defenders. The whole game-play consists of a campaign of 10 matches, 90 minutes each (15 hours total). After each match the game is saved on the Save Sheet. That gives the possibility to divide the whole campaign to as many parts as we need. The goal of each game is to survive all of the enemy assault waves. CONTENTS GAME COMPONENTS Symbols and defi nitions 3 • Game board Components overview 4 • Rulebook Setting up the game 7 • 26 building tokens • 28 building cards Selecting the Heroes 7 • 40 fortifi cation tokens Setting up the components 7 • 12 moat tokens The course of the game 8 • 12 ditch tokens • 4 enemy cards Round structure 8 • 19 technology cards I. -

A Short Text-Book on Masonry Construction, In- Cluding Descriptions of the Materials Used, Their Preparation and Arrangement in Structures

WORKS OF PROF. M. A. HOWE PUBLISHED BY JOHN WILEY & SONS, Inc. Masonry. A short Text-book on Masonry Construction, in- cluding Descriptions of the Materials Used, their Preparation and Arrangement in Structures. 8vo, ix +160 pages. 115 figures. Cloth, $1.50 net. Foundations. A short Text-book on Ordinary Foundations, including a brief Description of the Methods Used for Difficurt Foundations. 8vo, vii + 110 pages. 56 figures. Cloth, $1.25 net. Influence Diagrams for the Determination of Maximum Moments in Trusses and Beams 8vo, vii+65 pages, 42 figures. Cloth, $1.25 net. The Design of Simple Roof=trusses in Wood and Steel. With an Introduction to the Elements of Graphic Statics. Third edition, revised and enlarged. 8vo, vi+173 pages, 124 figures and 3 folding plates. Cloth, $1.80 net. Retaining-walls for Earth. Including the theory of Earth-pressure as Devel- oped from the Ellipse of Stress. With a Short Treatise on Foundations. Illustrated with Ex- amples from Practice. Sixth edition, revised and enlarged. 12mo, xv +194 pages, 110 figures. Cloth, $1.25 net. A Treatise on Arches. Designed for the use of Engineers and Students in Technical Schools. Second edition, revised and enlarged. 8vo, xxv +369 pages, 74 figures. Cloth, $4.00 net. Symmetrical Masonry Arches. Including Natural Stone, Plain concrete and Rein- forced concrete arches, for the use of Technical Schools, Engineers and Computers .in Designing Arches according to the Elastic Theory. Second edition, revised and enlarged. 8vo, xxiv -r245 pages. Profusely illustrated with figures in the text and folding plates. Cloth, $2.50 net. -

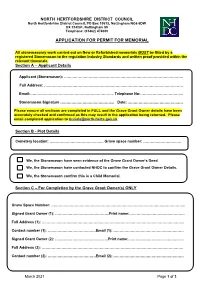

Application for Permit for Memorial

NORTH HERTFORDSHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL North Hertfordshire District Council, PO Box 10613, Nottingham NG6 6DW DX 324201, Nottingham 59 Telephone: (01462) 474000 APPLICATION FOR PERMIT FOR MEMORIAL All stonemasonry work carried out on New or Refurbished memorials MUST be fitted by a registered Stonemason to the regulation Industry Standards and written proof provided within the relevant timescale. Section A – Applicant Details Applicant (Stonemason): …………………………….……………………………………………………… Full Address: ………………………………………………………..………………………………………… Email:………………………………………………………….. Telephone No:…………………………….. Stonemason Signature …………………………………….. Date: ……………………………………… Please ensure all sections are completed in FULL and the Grave Grant Owner details have been accurately checked and confirmed as this may result in the application being returned. Please email completed application to [email protected] Section B - Plot Details Cemetery location: …………………………………….. Grave space number: …………………………. We, the Stonemason have seen evidence of the Grave Grant Owner’s Deed We, the Stonemason have contacted NHDC to confirm the Grave Grant Owner Details. We, the Stonemason confirm this is a Child Memorial. Section C – For Completion by the Grave Grant Owner(s) ONLY Grave Space Number: ………………………………………………………………………………………………. Signed Grant Owner (1): ……………………………………..Print name:……………………………………… Full Address (1): …………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Contact number (1): …………………………………Email (1): ………………………………………………… Signed Grant Owner (2): …………………………………….Print name:……………………………………… -

Italian Stoneworkers in America – Stonemasonry in Curitiba, Paraná (Brazil)

Italian stoneworkers in America – stonemasonry in Curitiba, Paraná (Brazil) Antonio Liccardo & Carlos Alberto Pereira Universidade Federal do Paraná and Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto - Brazil Interfaces of stonemasonry research • History • Culture • Geology • Mineral extraction • Mining engineering • Geography Stonemasonry technique is an ancient craft which came to Brazil from Europe with Portuguese and Spanish settlers. In Curitiba has also been developed through Italian colonization, producing stone works for pavements, walls, fountains, landmarks and monuments. Stonemasonry is considered to be an activity which is declining to extinction. Curitiba presents, besides countless works constructed with this technique, stonemason-artisans still in activity. Curitiba – most european of brazilian capitals • Curitiba is a city with about 2 million people, located in Southern Brazil • It was founded in 1693, but its development as a modern city began at the end of the 19th century because of geopolitical factors, and coincided with the beginning of the immigration Italian migration to Brazil • Italian immigration in Brazil occurred from 1860 until the 1940s • From 1875 until 1895 the migration of workers connected to urban services started, as builders, potters and, among them, stonemasons Greca family working stones in 1894 Researches about italian emigration show an exodus of stonemasons and stoneworkers in cities known for this activity, mainly in the Veneto region. Italian descendants working granite – Curitiba - 1928 General geology -

G:\Youth Services\Institutional and Industrial Education\Documents\Plans of Training\Febfinals\Word\Stonemason Pl00.Wpd

A PLAN OF TRAINING FOR STONEMASON OCCUPATION Approved by Provincial Apprenticeship Board April, 1997 Revised June, 2000 Foreword Apprenticeship training in the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador is undergoing considerable change. This change is prompted by the need to keep pace with technological changes in industry, the need to be competitive, and the desire to be efficient and effective in meeting the needs of the apprentice. We feel that this training plan will lay the groundwork to meet both the demands of industry and the needs of the apprentice. The plan that follows is a comprehensive one. It recognizes that apprenticeship training begins when a student first registers at a training institution, or signs a Contract of Apprenticeship with an employer, and continues until such time as the apprentice has completed all of the required technical training and has received the required industry experiences necessary to write an interprovincial examination. Passing this examination will result in the apprentice receiving Red Seal Certification which gives the tradesperson national mobility of trade qualifications. This plan also recognizes the need to provide flexible access to training based on the needs of the employer and the apprentice while at the same time recognizing the end goal is to complete the requirements for Red Seal Certification. It is realized that change in all facets of education and industry is continuous and sometimes rapid. This change will necessitate the review of this document on a continuous basis to ensure that current needs of industry and apprentices are being satisfied. Through a process of accreditation, regular input from industry advisory committees, as well as input from those involved in the administration and delivery of the training, we are confident that residents of our province who elect to pursue an apprenticeable trade as a career choice will receive high quality training and thus will be prepared to compete for jobs worldwide. -

STONEMASONRY Level 4

New Zealand Certificate in STONEMASONRY Level 4 Specifications October 2018 v1.2 Welcome to the Specifications that set out the technical content of the New Zealand Certificate in Stonemasonry (Level 4) with strands in Monumental Masonry, Construction Stonemasonry, and Natural Stone Fixtures and Fittings (with optional strands in Banker Masonry, and Conservation and Preservation) [Ref: 2737] These Specifications are, collectively, a prescription for achieving the requirements of the qualification. Together they describe what a person must be capable of to become a qualified trade professional. They are intended to support tertiary education organisations to develop programmes that detail how learning and assessment will occur. Programmes must encompass these Specifications and support the development of the skills, knowledge and attributes that reflect the technical competence, self-management, professionalism and leadership. 2 | Specifications required by the New Zealand Certificate in Stonemasonry (October 2018) v1.2 The individual skill sets included in these Specifications are designed to be read, interpreted and assessed together. This means that information contained in one skill set that is relevant to any other skill sets is stated only once, in the most appropriate place. However, the expectation is that assessment will look for links across skills sets. This avoids duplicating information and allows the candidate to be assessed holistically. Where the skills and knowledge included in one skill set are essential to achieving other -

Fortification in the XVI Century: the Case of Famagusta

02D0691 Project Number: MADOO1C 1 (p Fortification in the XVI Century: The Case of Famagusta An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By Matthew Cardinal and r Joseph Rennert Date: April 26, 2002 Approved: Professor Michael Demetriou, Advisor sc Professor Roberto Pietroforte, Advisor Table of Contents Chapter I- Introduction pages 1-6 Chapter II- Methodology pages 7-18 Chapter III- The Siege Warfare Before Gunpowder pages 19-26 Chapter IV- Defensive Architecture Before Gunpowder pages 27-32 Chapter V- Change: From Pre to Post Gunpowder pages 33- 38 Chapter VI- Defending Artillery pages 39- 47 Chapter VII- Venice, The Commercial Power pages 48-60 Chapter VIII- The Venetian Influences in Famagusta pages 61- 73 Chapter IX- Conclusion pages 74- 77 Appendix A pages 78- 81 Appendix B pages 82-82 Bibliography pages 83-84 Abstract The changes in the Sixteenth century of the fortifications surrounding Famagusta, Cyprus from pre to post gunpowder are studied. Methods of siege warfare and siege defense before and after the advent of artillery are compared. Literary research conducted describes evolutionary changes made in the engineering design of fortifications. The Venetian influence in the design of Famagusta's defensive structures due to the progression of Fourteenth to Sixteenth century military warfare demonstrates the effect engineering technology has on society. CHAPTER I Introduction Engineering design change has been a result of technological advances made by societies, both past and present. During the Renaissance period in the Mediterranean, the city of Venice (Fig. -

Exhibition Catalogue

Second Annual Exhibition Exhibition Catalogue About the Company A Word from the Master of the Company Dr Christine Ridgen The Worshipful Company of Masons is number 30 in the order of precedence of the ancient Livery I am very pleased to recommend to you this sale of masons’ work in Companies of the City of London, as set by the Aldermen of the City in 1515. Today there are over support of the Masons’ Company Craft Fund. This charity supports 110 and the number continues to grow. masons during their early years in the craft and is a potential lifeline for them. Without the financial support we give them they would have The focus of the Livery Company is to preserve and encourage the use of natural stone in the built a hard time and could indeed drop out of training, so for the long environment. This includes supporting the training of craftsmen as well as the preservation and term health of this ancient craft we ask for your support by buying appreciation of iconic historic stone buildings. an Item. Current Covid-19 Regulations prevent a repeat of the excellent open event which we held last year in Gallery Different, but in addition to viewing this catalogue, do contact the gallery directly if you would like a personal visit to see the works of art on display (government regulations permitting). Details of how to acquire an item of work are included within the catalogue together with full descriptions of those items available. This event celebrates the excellent work done by these gifted masons, please enjoy this catalogue and be generous in selecting items of stone for your house, garden or that very special Christmas present. -

Ancash, Peru), Ad 400–800

Fortifications as Warfare Culture Fortifications as Warfare Culture: the Hilltop Centre of Yayno (Ancash, Peru), ad 400–800 George F. Lau This article evaluates defensive works at the ancient hilltop centre of Yayno, Pomabamba, north highlands, Peru. Survey, mapping and sampling excavations show that its primary occupation dates to cal. ad 400–800, by groups of the Recuay tradition. At the centre of a network articulating small nearby farming villages, Yayno features an impressive series of natural and built defensive strategies. These worked in concert to protect the community from outsiders and keep internal groups physically segregated. The fortifications are discussed in relation to local political organization and a martial aesthetic in northern Peru during the period. Recuay elite identity and monumentalism arose out of local corporate traditions of hilltop dwelling and defence. Although such traditions are now largely absent in contemporary patterns of settlement, an archaeology of warfare at Yayno has repercussions for local understandings of the past. By now, it is axiomatic, albeit still highly provocative, promote recognition and judicious understandings of to assert that armed conflict contributed significantly warfare culture by describing the logic and historical to shaping the cultures of many past and present place of its practice. human societies (Keeley 1996; LeBlanc 2003). Quite This article examines the defensive works at rightly, it remains a sensitive topic for living descend- Yayno, a fortified centre in Peru’s north-central high- ants of groups and source communities, whose past lands, Department of Ancash (Fig. 1). It was very likely and histories are characterized as warlike or their cul- the seat of a powerful chiefly society in the Recuay tures under scrutiny as having related practices such tradition, cal.