LEADERSHIP in NIGERIA's PUBLIC SERVICE the Case of the Lagos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 UNIVERSITY PRESS PLC - LIST of UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND - Payment No: 28

UNIVERSITY PRESS PLC - LIST OF UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND - Payment No: 28 S/No NAME S/No NAME S/No NAME S/No NAME 1 ABAADAM LUCKY SUANU 71 ADEGOKE SALOMON A. 141 ADESOKAN MORADEYO AKINWALE 211 AGBOMEJI KASAKI IBISOMI 2 ABBA HAWWA'U, 72 ADEGOKE SOLOMON ADEGBOYEGA 142 ADESOKAN MURAINA ADENIYI 212 AGBOOLA AKINTOMIDE, 3 ABBA YAHAY BAURE 73 ADEGUNLOYE BOLUWAJI CHARLES 143 ADESOLA OLADEJI 213 AGBOOLA JOHN OLADEJO 4 ABDU MUSA 74 ADEIFE ISAIAH, ADEWOLE 144 ADESOLA-OJO IYABO OLUBISI 214 AGBOOLA OLUFEMI&ABIOLA .A 5 ABDU SAULAWA ABDUL-AZIZ 75 ADEIYE OLUKEMI 145 ADESOMI KEHINDE 215 AGBOR DAVID ABANG AGBOR 6 ABDULIAHI ALIYU ARDO 76 ADEJUMO ADEMOLA 146 ADESOMI MOJISOLA OLAJUMOKE 216 AGBORUME MARTINS AYO 7 ABDULLAHI TALATU 77 ADEJUMOBI OLASUMBO 147 ADESONA MUDASHIR ADENIYI 217 AGHASILI DENNIS CHIMBA ODUH 8 ABDULLAHI ZAINAB MUHAMMAD 78 ADEKAHUNSI BABATOPE MICHAEL 148 ADESOPE ALANI O 218 AGIDI HELEN EGINIME 9 ABDUL-WAHID TUNDE JAMIU 79 ADEKANYE TAIWO 149 ADESOPE YEKINI ADETUNJI 219 AGINAM BERNARD NWAFOR 10 ABE ADEWALE DAVID 80 ADEKEYE RASHEED AYODELE 150 ADESUNKANMI ANAT, ARAMIDE 220 AGINAM JAMES OKEKE 11 ABIODUN GANIYU ADIO 81 ADEKOLA BABATUNDE 151 ADESUYI DAMION AJIBOLA OLANREWAJU 221 AGODIMUO BENNETH 12 ABIOLA ALH/MRS EGBEYEMI ADIAT 82 ADEKOYA ADEBAYO SAMUEL 152 ADESUYI OLANREWAJU DAMION 222 AGOMUO MOSES UMEH 13 ABIOLA JIMOH ABIOLA 83 ADEKOYA ADEYINKA ADEREMI 153 ADESUYI OLUFUNKE BAMIDELE 223 AGU CYPRIAN OBIDIKE 14 ABIOYE EBENEZER OLUSOLA 84 ADEKOYA JUSTUS ADEKUNLE 154 ADETIFA JOHN AJIBADE 224 AGU MAXWELL NNABIKE 15 ABOLADE JOSEPH OLADEJO 85 ADEKOYA MICHAEL -

Northern Education Initiative Plus PY4 Quarterly Report Second Quarter – January 1 to March 31, 2019

d Northern Education Initiative Plus PY4 Quarterly Report Second Quarter – January 1 to March 31, 2019 DISCLAIMER This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Creative Associates International. Submission Date: April 30, 2019 Contract Number: AID-620-C-15-00002 October 26, 2015 – October 25, 2020 COR: Olawale Samuel Submitted by: Nurudeen Lawal, Acting Chief of Party, Northern Education Initiative Plus 38 Mike Akhigbe Street, Jabi, Abuja, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Northern Education Initiative Plus - PY4 Quarter 2 Report iii CONTENT 1. PROGRAM OVERVIEW ................................................................................................... 5 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................. 6 1.1 Program Description ...................................................................................... 8 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................ 12 2.1 Implementation Status ................................................................................. 15 Intermediate Result 1. Government systems strengthened to increase the number of students enrolled in appropriate, relevant, approved educational options, especially girls and out-of-school children (OOSC) in target locations ............................................................................. 15 Sub IR 1.1 Increased number of educational options (formal, NFLC) meeting -

Tuesday, 21St February, 2017

8TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECOND SESSION NO. 110 397 SENATE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday, 21st February, 2017 1. Prayers 2. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 3. Oaths 4. Announcements (if any) 5. Petitions PRESENTATION OF REPORTS 1. Report of the Committee on Trade and Investment Consumer Protection Act (Repeal & Re-enactment) Bill, 2017 (SB. 257) Sen. Fatima Raji-Rasaki (Ekiti Central) -That the Senate do receive the report of the Committee on Trade and Investment on the Consumer Protection Act (Repeal & Re-enactment) Bill, 2017 (SB. 257) – To be laid. 2. Report of the Committee on Works Federal Roads Maintenance Agency (Repeal & Re-enactment) Bill, 2017 (SB. 219) Sen. Kabiru Gaya (Kano South) -That the Senate do receive the report of the Committee on Works on the Federal Roads Authority Bill, 2017 (SB. 219) – To be laid. 3. Report of the Auditor General for the Federation Senate Leader -That the Senate do receive the report of the Auditor General for the Federation on the Accounts of the Federation of Nigeria for the year ended 31st December, 2015 Part 1 – To be laid. ORDERS OF THE DAY MOTIONS 1. The urgent need for the Federal Government to redeem Local Contractors Debts. Sponsor: Sen. Oluremi Tinubu (Lagos Central) Co-sponsors: Sen. Shehu Sani (Kaduna Central) Sen. Solomon O. Adeola (Lagos West) Sen. David Umaru (Niger East) Sen. Magnus Abe (Rivers East) Sen. Gbenga Ashafa (Lagos East) The senate: Notes that the Nigerian economy is experiencing difficult times caused by a slump in oil prices, with the result that a negative GDP (it shrank by 0.36% in the first quarter, 2.06% in the second quarter, and 2.24% in the third quarter) was recorded in three consecutive quarters of 2016. -

Legislative Control of the Executive in Nigeria Under the Second Republic

04, 03 01 AWO 593~ By AWOTOKUN, ADEKUNLE MESHACK B.A. (HONS) (ABU) M.Sc. (!BADAN) Thesis submitted to the Department of Public Administration Faculty of Administration in Partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of --~~·---------.---·-.......... , Progrnmme c:~ Petites Subventions ARRIVEE - · Enregistré sous lo no l ~ 1 ()ate :. Il fi&~t. JWi~ DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PUBLIC ADMIJISTRATION) Obafemi Awolowo University, CE\/ 1993 1le-Ife, Nigeria. 2 3 r • CODESRIA-LIBRARY 1991. CERTIFICATION 1 hereby certify that this thesis was prepared by AWOTOKUN, ADEKUNLE MESHACK under my supervision. __ _I }J /J1,, --- Date CODESRIA-LIBRARY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A work such as this could not have been completed without the support of numerous individuals and institutions. 1 therefore wish to place on record my indebtedness to them. First, 1 owe Professer Ladipo Adamolekun a debt of gratitude, as the persan who encouraged me to work on Legislative contrai of the Executive. He agreed to supervise the preparation of the thesis and he did until he retired from the University. Professor Adamolekun's wealth of academic experience ·has no doubt sharpened my outlciok and served as a source of inspiration to me. 1 am also very grateful to Professor Dele Olowu (the Acting Head of Department) under whose intellectual guidance I developed part of the proposai which culminated ·in the final production qf .this work. My pupilage under him i though short was memorable and inspiring. He has also gone through the entire draft and his comments and criticisms, no doubt have improved the quality of the thesis. Perhaps more than anyone else, the Almighty God has used my indefatigable superviser Dr. -

Obi Patience Igwara ETHNICITY, NATIONALISM and NATION

Obi Patience Igwara ETHNICITY, NATIONALISM AND NATION-BUILDING IN NIGERIA, 1970-1992 Submitted for examination for the degree of Ph.D. London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 1993 UMI Number: U615538 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615538 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 V - x \ - 1^0 r La 2 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the relationship between ethnicity and nation-building and nationalism in Nigeria. It is argued that ethnicity is not necessarily incompatible with nationalism and nation-building. Ethnicity and nationalism both play a role in nation-state formation. They are each functional to political stability and, therefore, to civil peace and to the ability of individual Nigerians to pursue their non-political goals. Ethnicity is functional to political stability because it provides the basis for political socialization and for popular allegiance to political actors. It provides the framework within which patronage is institutionalized and related to traditional forms of welfare within a state which is itself unable to provide such benefits to its subjects. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

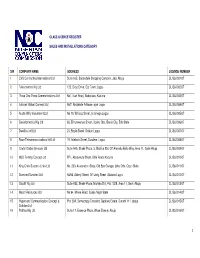

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

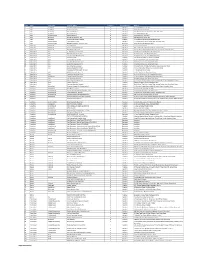

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. -

Lagos State Poctket Factfinder

HISTORY Before the creation of the States in 1967, the identity of Lagos was restricted to the Lagos Island of Eko (Bini word for war camp). The first settlers in Eko were the Aworis, who were mostly hunters and fishermen. They had migrated from Ile-Ife by stages to the coast at Ebute- Metta. The Aworis were later reinforced by a band of Benin warriors and joined by other Yoruba elements who settled on the mainland for a while till the danger of an attack by the warring tribes plaguing Yorubaland drove them to seek the security of the nearest island, Iddo, from where they spread to Eko. By 1851 after the abolition of the slave trade, there was a great attraction to Lagos by the repatriates. First were the Saro, mainly freed Yoruba captives and their descendants who, having been set ashore in Sierra Leone, responded to the pull of their homeland, and returned in successive waves to Lagos. Having had the privilege of Western education and christianity, they made remarkable contributions to education and the rapid modernisation of Lagos. They were granted land to settle in the Olowogbowo and Breadfruit areas of the island. The Brazilian returnees, the Aguda, also started arriving in Lagos in the mid-19th century and brought with them the skills they had acquired in Brazil. Most of them were master-builders, carpenters and masons, and gave the distinct charaterisitics of Brazilian architecture to their residential buildings at Bamgbose and Campos Square areas which form a large proportion of architectural richness of the city. -

DAVID OLUGBENGA OGUNGBILE Professor of Religious Studies

Professor David Olugbenga 0~lingbil6 B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Ife), MTS (Marvard), I'hD (lfc) Professor of Religio~rsSrlrdicc. TRULY, THE SACRED STILL DWELLS: MAKING SENSE OF EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN WORLD An Inaugural Lecture Delivered at Oduduwa Hall, Obafemi ~wolowoUniversity, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. On Tuesday, July 10, 2018. DAVID OLUGBENGA OGUNGBILE Professor of Religious Studies Inaugural Lecture Series 322 avid Olugbenga 0gungbile i1.A. (lfc). MTS (Har\,ard),I'hl) (112) ~/[,,S,TO~of'Rc~ligioi~.s .Ytz/(iic~.s Q OBAFEMI AWOLOWO UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2018 ISSN 01 89-7848 Printed by Obafemi Awolowo University Press Limited, Ile-Ife, Nigeria Truly, the Sacred Still Dwells: Making Sense of Existence in the African World )LOM.'O UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2018 Prolegornenon/Prelirninary Remarks The Inaugural Lecture is noted for providing rare opportunities to Professors so as to increase both their research and academic visibility. They are able to publicly declare and expound their past, present and future research endeavours. Mr Vice Chancellor Sir, Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen, I feel so honoured and humbled to be presenting today, the second Inaugural Lecture in the Department of Religious Studies of this great University, since its establishment in September, 1962. The first and only inaugural lecturer before me was Prof Matthews Ojo. All glory to the Lord! Religious Studies was one of the foundation disciplines in the Faculty of Arts and was initially run alongside Philosophy until the 1975176 ISSN 0189-7848 Academic Session when they became separate Departments. Since its inception, it has continued to offer the B.A. Religious Studies (Single Honours) and Religious Studies (Combined) with History, English or Philosophy Programme. -

Northern Education Initiative Plus PY4 Q3 Report April 1 – June 30, 2019

Northern Education Initiative Plus PY4 Q3 Report April 1 – June 30, 2019 DISCLAIMER This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Creative Associates International. Submission Date: July 31, 2019 Contract Number:AID-620-C-15-00002 October 26, 2015 – October 25, 2020 COR: Nura Ibrahim Submitted by: Jordene Hale, Chief of Party The Northern Education Initiative Plus 38 Mike Akhigbe Street, Jabi,Abuja, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Northern Education Initiative Plus - PY4 Quarter 3 Report 3 CONTENT 1. PROGRAM OVERVIEW .................................................................................................5 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................6 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................10 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .........................................................................................12 2.1 Implementation Status ..................................................................................16 Intermediate Result 1. Government systems strengthened to increase the number of students enrolled in appropriate, relevant, approved educational options, especially girls and out-of-school children (OOSC) in target locations ..............................................................................16 Sub IR 1.1 Increased number of educational options (formal, NFLC) meeting school quality and safety benchmarks: .............................................16 -

Public Disclosure Authorized

INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION THE INSPECTION PANEL 1818 H Street, N.W. Telephone: (202) 458-5200 Washington, D.C. 20433 Fax: (202) 522-0916 Email: [email protected] Eimi Watanabe Chairperson Public Disclosure Authorized JPN REQUEST RQ13/09 July 16, 2014 MEMORANDUM TO THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS OF THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Request for Inspection Public Disclosure Authorized NIGERIA: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P071340) Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions Please find attached a copy of the Memorandum from the Chairperson of the Inspection Panel entitled "Request for Inspection - Nigeria: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P071340) - Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions", dated July 16, 2014 and its attachments. This Memorandum was also distributed to the President of the International Development Association. Public Disclosure Authorized Attachment cc.: The President Public Disclosure Authorized International Development Association INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION THE INSPECTION PANEL 1818 H Street, N.W. Telephone: (202) 458-5200 Washington, D.C. 20433 Fax : (202) 522-0916 Email: [email protected] Eimi Watanabe Chairperson IPN REQUEST RQ13/09 July 16, 2014 MEMORANDUM TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Request for Inspection NIGERIA: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P071340) Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions Please find attached a copy of the Memorandum from the Chairperson of the Inspection Panel entitled "Request for Inspection - Nigeria: Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (P07 J340) - Notice of Non Registration and Panel's Observations of the First Pilot to Support Early Solutions" dated July 16, 2014 and its attachments.