Liquefied Natural Gas (Lng) Litigation After the Energy Policy Act of 2005: State Powers in Lng Terminal Siting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

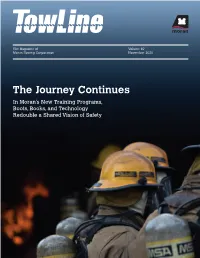

The Journey Continues

The Magazine of Volume 67 Moran Towing Corporation November 2020 The J our ney Continu es In Moran’s New Training Programs, Boots, Books, and Technology Redouble a Shared Vision of Safety PHOTO CREDITS Page 25 (inset) : Moran archives Cover: John Snyder, Pages 26 –27, both photos: marinemedia.biz Will Van Dorp Inside Front Cover: Pages 28 –29: Marcin Kocoj Moran archives Page 30: John Snyder, Page 2: Moran archives ( Fort marinemedia.biz Bragg ONE Stork ); Jeff Thoresen ( ); Page 31 (top): Dave Byrnes Barry Champagne, courtesy of Chamber of Shipping of America Page 31 (bottom): John Snyder, (CSA Environmental Achievement marinemedia.biz Awards) Pages 32 –33: John Snyder, Page 3 : Moran archives marinemedia.biz Pages 5 and 7 –13: John Snyder, Pages 3 6–37, all photos: Moran marinemedia.biz archives Page 15 –17: Moran archives Page 39, all photos: John Snyder, marinemedia.biz Page 19: MER archives Page 40: John Snyder, Page 20 –22: John Snyder, marinemedia.biz marinemedia.biz; Norfolk skyline photo by shutterstock.com Page 41: Moran archives Page 23, all photos: Pages 42 and 43: Moran archives Will Van Dorp Inside Back Cover: Moran Pages 24 –25: Stephen Morton, archives www.stephenmorton.com The Magazine of Volume 67 Moran Towing Corporation November 2020 2 News Briefs Books 34 Queen Mary 2: The Greatest Ocean Liner of Our Time , by John Maxtone- Cover Story Graham 4 The Journey Continues Published by Moran’s New Training Programs Moran Towing Corporation Redouble a Shared Vision of Safety The History Pages 36 Photographic gems from the EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Grandone family collection Mark Schnapper Operations REPORTER John Snyder 14 Moran’s Wellness Program Offers Health Coaching Milestones DESIGN DIRECTOR Mark Schnapper 18 Amid Continued Growth, MER Is 38 The christenings of four new high- Now a Wholly Owned Moran horsepower escort tugs Subsidiary People Moran Towing Corporation Ship Call Miles tones 40 50 Locust Avenue Capt. -

Transcanada Pipelines Limited Annual Information Form

TRANSCANADA PIPELINES LIMITED ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM February 23, 2009 TRANSCANADA PIPELINES LIMITED i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PRESENTATION OF INFORMATION..................................................................................................................................................ii FORWARD-LOOKING INFORMATION..............................................................................................................................................ii TRANSCANADA PIPELINES LIMITED............................................................................................................................................... 1 Corporate Structure ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Intercorporate Relationships............................................................................................................................................................... 1 GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BUSINESS .............................................................................................................................. 2 Developments in the Pipelines Business............................................................................................................................................. 2 Developments in the Energy Business............................................................................................................................................... -

Natural Gas the Composition of Natural Gas Is 95% Methane, Almost

Natural gas The composition of natural gas is 95% methane, almost 4% ethane and nitrogen, and 1% carbon dioxide and propane. It is produced by the natural transformation of organic materials over millions of years. Methane: the simplest hydrocarbon Methane gas belongs to the hydrocarbon family. A hydrocarbon is an organic composition that contains only carbon and hydrogen atoms. With just one carbon atom and four hydrogen atoms, methane (CH4) is the simplest hydrocarbon. Some other hydrocarbons are: propane (C3H8), ethane (C2H6) and butane (C4H10). Benefits of Natural Gas Natural gas is increasingly the fuel of choice in today's homes. Below are the top reasons to choose natural gas for your home. 1 | Affordability Natural gas costs less to use in your home than electricity, heating oil, propane or kerosene. On average, electricity costs almost four times more than natural gas. 2 | Convenience and reliability Natural gas is piped directly into your home. It's always there when you need it, and you never have to worry about running out of fuel or arranging for deliveries. 3 | Comfort Natural gas heat feels warmer than heat produced by an electric heat pump. 4 | Domestic supply Nearly 100% of the natural gas consumed in the U.S. is produced in North America with 90% coming directly from the U.S. 5 | Environmental impact Simply put - natural gas is the cleanest-burning energy source for your home. The combustion of natural gas emits 45% less carbon dioxide than coal. 6 | Energy efficiency Natural gas is highly efficient. About 90% of the natural gas produced is delivered to customers as useful energy. -

Special Anniversary Issue Moran’S Mexican Debut Is up and Running Milestones

The Magazine of Volume 63 Moran Towing Corporation November 2010 Special Anniversary Issue Moran’s Mexican Debut Is Up and Running Milestones 34 miles north of Ensenada, tug’s motion, thereby preventing snap-loads and Mexico, in Pacific waters breakage. This enables the tug to perform opti- just off the Mexican Baja, mally, at safe working loads for the hawser, under Moran’s SMBC joint ven- a very wide range of sea state and weather condi- ture (the initials stand for tions. The function is facilitated by sensors that Servicios Maritimos de Baja continuously detect excess slack or tension on the California) has been writ- line, and automatically compensate by triggering 15ing a new chapter in the company’s history. either spooling or feeding out of line in precise- SMBC, a joint venture with Grupo Boluda ly the amounts necessary to maintain a pre-set Maritime Corporation of Spain, has been operat- standard of tension. ing at this location since 2008. It provides ship To a hawser-connected tug and tanker snaking assist, line handling and pilot boat services to over the crests of nine-foot swells, this equipment LNG carriers calling at Sempra LNG’s Energia is as indispensable as a gyroscope is to a rocket; its Costa Azul LNG terminal. stabilizing effect on the motion of the lines and SMBC represents a new maritime presence in vessels gives the mariners complete control. North American Pacific coastal waters. Each of its As part of this capability, upper and lower load tugs bears dual insignias on its stacks: the Moran ranges can be digitally selected and monitored “M” and Boluda’s “B”. -

Energy Assurance Daily, June 22, 2010

ENERGY ASSURANCE DAILY Tuesday Evening, June 22, 2010 Major Developments Update: Federal Judge Blocks Government-Imposed Deepwater Drilling Moratorium A U.S. District Judge blocked the federal government's six-month moratorium on deepwater drilling, saying it seemed clear "that the federal government had been pressed by what happened on the Deepwater Horizon into an otherwise sweeping confirmation that all Gulf deepwater drilling activities put us all in a universal threat of irreparable harm." Numerous service companies had asked the judge to reject the moratorium, saying the government had imposed it arbitrarily. The Obama Administration said it would immediately appeal the decision. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/06/22/AR2010062200237.html?wpisrc=nl_natlalert BP Recovers About 25,830 Barrels of Oil at Site of Blown-Out Well in Gulf of Mexico June 21 BP collected about 15,560 barrels of oil, flared approximately 10,270 barrels of oil, and flared about 52.2 million cubic feet of natural gas on June 20 via its dual collection system at the blown-out MC252 well in the Gulf of Mexico, the company said on its website. http://www.bp.com/extendedsectiongenericarticle.do?categoryId=40&contentId=7061813 Update: U.S. CSB to Investigate Deepwater Horizon Explosion The U.S. Chemical Safety Board (CSB) plans to investigate the root causes of the April 20 explosion onboard the Deepwater Horizon rig in the Gulf of Mexico. The CSB expects to include the key investigators who were involved in its investigation of the March 23, 2005 explosion at BP’s Texas City refinery. -

GIIGNL Annual Report Profile

The LNG industry GIIGNL Annual Report Profile Acknowledgements Profile We wish to thank all member companies for their contribution to the report and the GIIGNL is a non-profit organisation whose objective following international experts for their is to promote the development of activities related to comments and suggestions: LNG: purchasing, importing, processing, transportation, • Cybele Henriquez – Cheniere Energy handling, regasification and its various uses. • Najla Jamoussi – Cheniere Energy • Callum Bennett – Clarksons The Group constitutes a forum for exchange of • Laurent Hamou – Elengy information and experience among its 88 members in • Jacques Rottenberg – Elengy order to enhance the safety, reliability, efficiency and • María Ángeles de Vicente – Enagás sustainability of LNG import activities and in particular • Paul-Emmanuel Decroës – Engie the operation of LNG import terminals. • Oliver Simpson – Excelerate Energy • Andy Flower – Flower LNG • Magnus Koren – Höegh LNG • Mariana Ortiz – Naturgy Energy Group • Birthe van Vliet – Shell • Mika Iseki – Tokyo Gas • Yohei Hukins – Tokyo Gas • Donna DeWick – Total • Emmanuelle Viton – Total • Xinyi Zhang – Total © GIIGNL - International Group of Liquefied Natural Gas Importers All data and maps provided in this publication are for information purposes and shall be treated as indicative only. Under no circumstances shall they be regarded as data or maps intended for commercial use. Reproduction of the contents of this publication in any manner whatsoever is prohibited without prior -

Power Sector Reform

EVOLVING PERSPECTIVES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF INDIAN INFRASTRUCTURE EVOLVING PERSPECTIVES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF INDIAN INFRASTRUCTURE Volume 1 Infrastructure Development Finance Company Limited ORIENT BLACKSWAN PRIVATE LIMITED Registered office 3-6-752 Himayatnagar, Hyderabad 500 029 (A.P.), India Email: [email protected] Other offices Bangalore, Bhopal, Bhubaneshwar, Chennai Ernakulam, Guwahati, Hyderabad, Jaipur, Kolkata, Lucknow, Mumbai, New Delhi, Noida, Patna © Infrastructure Development Finance Company Limited 2012 First published 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Orient Blackswan Private Limited. ISBN 978 81 250 4666 0 Typeset in Minion 11/14 by Trendz Phototypesetters, Mumbai 400 001 Printed in India at Aegean Offset Printers, Greater Noida Published by Orient Blackswan Private Limited 1/24 Asaf Ali Road New Delhi 110 002 E-mail: [email protected] The external boundary and coastline of India as depicted in the maps in this book are neither correct nor authentic. CONTENTS List of Tables, Figures and Boxes vii Foreword by Rajiv B. Lall xv Acknowledgements xvii Introduction xix List of Abbreviations xxiii ENERGY 1 Power Sector Reform: Policy Decisions in Distribution 3 2 Power Sector in India: A Summary Description 13 3 Power Sector Reform in Argentina: A Summary Description 22 4 Orissa -

The Pioneer December 2013

ISSUE 142 - DECEMBER 2013 DELIVERING ON OUR PROMISE CEO Address - page 1 New reem al harami surpassiNg successful winner of the Qatar safety SALES aNd PURCHASE busiNess womeN millstoNes AGREEMENTS award 2013 2Nd doha CSR New carboN aNd sustaiNability Qatargas league eNergy forum awards kicks off In this issue DEcEMBER 2013 12 16 30 44 OPERATING People Main EVENTs Corporate sOcial EXcELLENcE responsibility 2 Plateau Maintenance 15 Winter Camp 2013/2014 28 5th Hydrate Forum 34 Sustainability Reporting Project Achieves A desert haven th a Winner Significant Safety 29 8 Doha International 16 An interview with Oil & Gas Exhibition 35 JBOG wins Sustainability Milestone Award at O&G Year 2013 Reem Mohammad 9th GCC Economic 4 CEO shares insights and New Qatargas League Al-Harami Symposium in Stockholm 36 predictions at SIEW kicks off 18 An interview with nd 6 Qatargas MD delivers 30 2 Doha Carbon 38 Big on badminton keynote speech at Fatima Al-Mohannadi and Energy Forum 40 Golf Open reaches the 15th GAS Singapore 20 Shareholders’ Spotlight 31 Contractors’ 1st 7 Qatargas signs SPA Satoru Shibuta, 41 Golf Juniors tee Engineering off for 4th time with E.ON for 5-year GM, Cosmo Oil, Doha 32 LNG delivery Collaboration 42 Qatargas Pearl Sponsor 22 New Year 33 Safety Talk of Ice Hockey Season 8 5-year SPA with New Challenges PETRONAS LNG (UK) 43 First Qatargas Open 9 Qatargas and Centrica 24 ‘Best National Team’ Chess Tournament sign 4 year agreement at MOQP Challenge 2013 44 Ben Barbour A journey in art 10 JBOG achieves another 24 33 safety milestone 48 Qatar UK‒Celebrating a 11 Chubu Electric delegation Year of Cultural Exchange visits Ras Laffan 49 Qatargas engineers join 12 LNG first deliveries bolster Qatar Society of Engineers China trade 50 Supporting relief efforts around the world VIsITs 54 13 years of Blood Donation 55 Second QP Occupational 14 Global Environment Health Conference Exchange Visit by 56 Al Khor Community.. -

Liquefied Natural Gas: Understanding the Basic Facts Liquefied Natural Gas: Understanding The

Liquefied Natural Gas: Understanding the Basic Facts Liquefied Natural Gas: Understanding the “I strongly support developing new LNG capacity in the United States.” —President George W. Bush Page 2 4 Growing Demand Emergence of the for Natural Gas Global LNG Market About This Report Natural gas plays a vital role in One of several proposed the U.S. energy supply and in supply options would involve This report was prepared by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) in achieving the nation’s economic increasing imports of liquefied collaboration with the National and environmental goals. natural gas (LNG) to ensure Association of Regulatory Utility that American consumers have Although natural gas production Commissioners (NARUC). DOE’s Office of adequate supplies of natural in North America is projected Fossil Energy supports technology gas in the future. research and policy options to ensure to gradually increase through clean, reliable, and affordable supplies 2025, consumption has begun Liquefaction enables natural of oil and natural gas for American to outpace available domestic gas that would otherwise be consumers, working closely with the National Energy Technology Laboratory, natural gas supply. Over time, “stranded” to reach major which is the Department’s lead center this gap will widen. markets. Developing countries for the research and development of with plentiful natural gas advanced fossil energy technologies. resources are particularly NARUC, a nonprofit organization interested in monetizing composed of governmental agencies engaged in the regulation of natural gas by exporting it as telecommunications, energy, and water LNG. Conversely, more utilities and carriers in the 50 states, the developed nations with little District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and or no domestic natural gas the Virgin Islands, serves the public rely on imports. -

Winch and HMPE Rope Limitations

Day 2 Amsterdam, The Netherlands Paper No. 1 Organised by the ABR Company Ltd High Performance Winches for High Performance Tugs – Winch and HMPE Rope Limitations Barry Griffi n, BA Griffi n Associates, Bainbridge Island, WA, USA Gary Nishimura, Markey Machinery Company, Seattle, WA, USA SYNOPSIS In the past two years, Markey Machinery Company has been expanding its line of High Performance Render/Recover™ Hawser Winches to meet the demands for escort tugs that are being called upon to operate under increasingly strenuous offshore conditions. The new fl agship model is four 760hp DESDF-48WF-760hp double drum hawser winches developed for Moran Towing and Groupo Boluda for use on tugs to be based at the new Energia Costa Azul LNG terminal located near Ensenada, Mexico on the Baja California peninsula. These tugs are required to bring tankers to dock in 3m 10-second period sea conditions and were preceded by 100hp, 200hp and 250hp versions developed for other customers. Markey is employing cutting-edge technologies such as 3D-modelling, fi nite element analysis and numerical modelling in conjunction with model-testing to increase its capability to produce designs that meet the increasingly demanding requirements for ship assist and escort. As a contributing partner in the Marin Safe Tug project, the company is working to improve the overall safety and effi ciency of the companies that operate at exposed offshore and near-shore terminals. INTRODUCTION 20 years reveals increases in winch power from 55kW The Markey ARR winches and PSR Plasma HMPE to more than 550kW, generally without commensurate ropes fi tted to tugs servicing Sempra Energy’s Energia increases in tug direct bollard pull. -

A Review of Best Available Technology in Tanker Escort Tugs

ROBERT ALLAN LTD. NAVAL ARCHITECTS A Review of Best Available Technology in Tanker Escort Tugs Project 212-090 Revision 3 November 6, 2013 Prepared for: Prince William Sound Regional Citizens' Advisory Council Anchorage, AK Prepared by: Robert Allan Ltd. Naval Architects and Marine Engineers 230 - 1639 West 2nd Avenue Vancouver, BC V6J 1H3 Canada The opinions expressed in this PWSRCAC-commissioned report are not necessarily those of PWSRCAC. ROBERT ALLAN LTD. NAVAL ARCHITECTS A Review of Best Available Technology in Tanker Escort Tugs Document No.: 212-090 Prepared For: Client's Reference: Prince William Sound Regional Contract No. 8010.12.01 Citizens' Advisory Council Anchorage, AK Prepared By: Professional Engineer of Record: Robert G. Allan, P. Eng. Robert G. Allan, P. Eng. Brendan Smoker, M.A.Sc. Revision History Final mods per Client review: 3 RGA RGA RGA RGA Nov. 6, 13 notes re CFR 33 168 added DRAFT 2 Second Issue RGA RGA RGA RGA Sept. 3, 13 DRAFT First Issue RGA RGA RGA RGA Aug. 2, 13 P. Eng. of Rev. Description By Checked Record Approved Issue Date Class Approval Status Client Acceptance Status Rev. Approval Agency Initials Date Rev. Design Phase Initials Date Confidentiality: Confidential All information contained in or disclosed by this document is proprietary and the exclusive intellectual property of Robert Allan Ltd. This design information is reserved for the exclusive use of Prince William Sound Regional Citizens' Advisory Council of Anchorage, AK, all further use and sales rights attached thereto are exclusively reserved by Robert Allan Ltd., and any reproduction, communication or distribution of this information is prohibited without the prior written consent of Robert Allan Ltd. -

Congressional Record—House H6757

June 20, 2007 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H6757 Board of Visitors to the United States I would ask the chairman if he would ADERHOLT to restore funding for the Air Force Academy: work with Mr. LIPINSKI, the gentleman ARC, Appalachian Regional Commis- Mr. DEFAZIO, Oregon from Illinois, and me to provide fund- sion, to $65 million in this bill. This Ms. LORETTA SANCHEZ, California ing for the H-Prize as we move forward amendment brings the Commission’s Mr. LAMBORN, Colorado in conference with the Senate. funding up so that it’s equal to the f Mr. VISCLOSKY. Mr. Chairman, I ap- President’s request in the previous preciate the gentleman and Mr. LIPIN- year’s funding level. ENERGY AND WATER DEVELOP- SKI’s request for funding for this very The Appalachian Regional Commis- MENT AND RELATED AGENCIES worthwhile program, and certainly sion is very important to my district APPROPRIATIONS ACT, 2008 look forward to working with him as and many other districts from New The SPEAKER pro tempore. Pursu- well as the gentleman from Illinois as York to Mississippi. The Appalachian ant to House Resolution 481 and rule we go to conference. Regional Commission is a model for XVIII, the Chair declares the House in Mr. INGLIS of South Carolina. I Federal economic development initia- the Committee of the Whole House on thank the gentleman. tives, and has been a responsible stew- the state of the Union for the further The Acting CHAIRMAN. The Clerk ard of the Federal funds it has received consideration of the bill, H.R. 2641.