Out of the Silence: a Celebration of Music PROGRAM THREE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PLATTEGROND VAN HET CONCERTGEBOUW Begane Grond 1E

PLATTEGROND VAN HET CONCERTGEBOUW JULI AUGUSTUS Begane grond Entree Café Woensdag 2 augustus 2017 Trap Trap T Grote Zaal 20.00 uur Zuid Würth Philharmoniker Achterzaal Garderobe Dennis Russell Davies, dirigent Voorzaal Podium Robeco Ray Chen, viool Grote Zaal Summer Restaurant Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 1756-1791 Symfonie nr. 32 in G, KV 318 (1779) Noord Allegro spiritoso Andante Trap Trap Primo tempo Felix Mendelssohn 1809-1847 Vioolconcert in e, op. 64 (1844) Allegro molto appassionato 1e verdieping Andante Pleinfoyer Allegretto non troppo - Allegro molto vivace Museum- SummerNights Live! foyer PAUZE T Trap Trap Antonín Dvořák 1841-1904 Solistenfoyer Negende symfonie in e, op. 95 ‘Uit de Balkon Zuid Nieuwe Wereld’ (1893) Podium Adagio - Allegro molto Frontbalkon Largo Scherzo: Molto vivace Kleine Zaal Grote Zaal Allegro con fuoco Muziek beleven doet u samen. Veel van Podium Balkon Noord onze bezoekers willen optimaal van de muziek genieten door geconcentreerd en in stilte te Dirigenten- luisteren. Wij vragen u daar rekening mee te Trap foyer Trap houden. WWW.ROBECOSUMMERNIGHTS.NL Informatiebeveiliging in de ambulancezorg Toelichting/TOELICHTING/Biografie//Summary//Concerttip BIOGRAFIE SUMMARYjuli-aug 2015 EN VERDER... In januari 1779 keerde Wolfgang Amadeus het nieuwe vioolconcert was onder meer dat De Würth Philharmoniker draagt de naam When Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart worked as Social media Robeco Mozart van zijn reis naar Parijs terug in de solist meteen met de deur in huis komt van zijn initiatiefnemer: de Duitse onderne- the court organist for Count Archbishop Salzburg, waar zijn (ongelukkige) dienstver- vallen, dat de solocadens niet aan het eind mer en mecenas Reinhold Würth. Het gloed- Colloredo in Salzburg, he was expected to Meer Robeco SummerNights online! De Robeco SummerNights komen voort uit band bij prins-aartsbisschop Colloredo werd van het eerste deel zit maar veel eerder, en nieuwe orkest, met het juist gebouwde provide new compositions for the court and Volg Het Concertgebouw op social media en een unieke samenwerking tussen Robeco en voortgezet. -

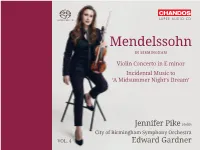

Mendelssohn in BIRMINGHAM

SUPER AUDIO CD Mendelssohn IN BIRMINGHAM Violin Concerto in E minor Incidental Music to ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ Jennifer Pike violin City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra VOL. 4 Edward Gardner Painting by Thomas Hildebrandt (1804 – 1874) / Stadtgeschichtliches Museum, Leipzig / AKG Images, London Felix Mendelssohn, 1845 Mendelssohn, Felix Felix Mendelssohn (1809 – 1847) Mendelssohn in Birmingham, Volume 4 Concerto, Op. 64* 27:56 in E minor • in e-Moll • en mi mineur for Violin and Orchestra 1 Allegro molto appassionato – Cadenza ad libitum – Tempo I – Più presto – Sempre più presto – Presto – 12:55 2 Andante – Allegretto non troppo – 9:01 3 Allegro molto vivace 6:00 Incidental Music to ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’, Op. 61† 39:44 (Ein Sommernachtstraum) by William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616) 4 Overture (Op. 21). Allegro di molto – [ ] – Tempo I – Poco ritenuto 11:25 5 1 Scherzo (After the end of the first act). Allegro vivace 4:30 6 3 Song with Chorus. Allegro ma non troppo 3:57 7 5 Intermezzo (After the end of the second act). Allegro appassionato – Allegro molto comodo 3:21 3 8 7 Notturno (After the end of the third act). Con moto tranquillo 5:34 9 9 Wedding March (After the end of the fourth act). Allegro vivace 4:30 10 11 A Dance of Clowns. Allegro di molto 1:33 11 Finale. Allegro di molto – Un poco ritardando – A tempo I. Allegro molto 4:28 TT 67:57 Rhian Lois soprano I† Keri Fuge soprano II† Jennifer Pike violin* CBSO Youth Chorus† Julian Wilkins chorus master City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Zoë Beyers leader Edward Gardner 4 Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in E minor / A Midsummer Night’s Dream Introduction fine violinist himself. -

SWR2 Musikstunde

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT ESSAYS FEATURES KOMMENTARE VORTRÄGE SWR2 Musikstunde Dänische Entdeckungen (1) Niels Wilhelm Gade und Carl Nielsen Von Jörg Lengersdorf Sendung: Montag, 27. Juli 2015 9.05 – 10.00 Uhr Redaktion: Ulla Zierau Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Mitschnitte auf CD von allen Sendungen der Redaktion SWR2 Musik sind beim SWR Mitschnittdienst in Baden-Baden für € 12,50 erhältlich. Bestellungen über Telefon: 07221/929-26030 Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2-Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de SWR2 Musikstunde, 27. Juli 2015 Dänische Entdeckungen (1) Niels Wilhelm Gade und Carl Nielsen Man kann beide wohl getrost als die wichtigsten Symphoniker der dänischen Musikgeschichte bezeichnen, Niels Wilhelm Gade und Carl Nielsen. Obwohl letzterer kurzzeitig Schüler des ersteren war, trennt hörbar ein halbes Jahrhundert Kulturhistorie die beiden Männer. Dass Lehrer Gade seinen Schüler Nielsen irgendwie nachhaltig beeinflusst haben könnte, lässt sich musikalisch kaum nachweisen. Niels Wilhelm Gade wurde kurz vor seinem Tod endgültig wahrgenommen als ein großer Konservativer der europäischen Musik, ein Mann der Rückschau ins 19. Jhd. Und es waren just jene Umbruchsjahre, in denen der junge Carl Nielsen die dänische Musik auf ein neues, völlig anders klingendes, Jahrhundert vorbereiten sollte. Beiden Komponisten ist die SWR2 Musikstunde dieser Woche gewidmet, denn beide, Gade wie Nielsen, wurden auf unterschiedliche Art und Weise volkstümlich im nördlichen Nachbarland. -

Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds

EDVARD GRIEG: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS EDVARD GRIEG: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS By REBEKAH JORDAN A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Rebekah Jordan, April, 2003 MASTER OF ARTS (2003) 1vIc1vlaster University (1vIllSic <=riticisIll) HaIllilton, Ontario Title: Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds Author: Rebekah Jordan, B. 1vIus (EastIllan School of 1vIllSic) Sllpervisor: Dr. Hllgh Hartwell NUIllber of pages: v, 129 11 ABSTRACT Although Edvard Grieg is recognized primarily as a nationalist composer among a plethora of other nationalist composers, he is much more than that. While the inspiration for much of his music rests in the hills and fjords, the folk tales and legends, and the pastoral settings of his native Norway and his melodic lines and unique harmonies bring to the mind of the listener pictures of that land, to restrict Grieg's music to the realm of nationalism requires one to ignore its international character. In tracing the various transitions in the development of Grieg's compositional style, one can discern the influences of his early training in Bergen, his four years at the Leipzig Conservatory, and his friendship with Norwegian nationalists - all intricately blended with his own harmonic inventiveness -- to produce music which is uniquely Griegian. Though his music and his performances were received with acclaim in the major concert venues of Europe, Grieg continued to pursue international recognition to repudiate the criticism that he was only a composer of Norwegian music. In conclusion, this thesis demonstrates that the international influence of this so-called Norwegian maestro had a profound influence on many other composers and was instrumental in the development of Impressionist harmonies. -

Where No Wall Remains ﺣﯾث ﻻ ﺟدار ﯾﺑﻘﯽ Donde No Queda Ningún Muro

LIVE ARTS BARD 2019 BIENNIAL Where No Wall Remains حيث ﻻ جدار يبقى Donde No Queda Ningún Muro an international festival about borders NOVEMBER 21–24, 2019 About the Fisher Center at Bard Fisher Center at Bard The Fisher Center develops, produces, and presents performing arts across disciplines Chair Jeanne Donovan through new productions and context-rich programs that challenge and inspire. As President Leon Botstein a premier professional performing arts center and a hub for research and education, Executive Director Bob Bursey the Fisher Center supports artists, students, and audiences in the development and Artistic Director Gideon Lester examination of artistic ideas, offering perspectives from the past and present, as well present as visions of the future. The Fisher Center demonstrates Bard’s commitment to the performing arts as a cultural and educational necessity. Home is the Fisher Center LIVE ARTS BARD 2019 BIENNIAL for the Performing Arts, designed by Frank Gehry and located on the campus of Bard College in New York’s Hudson Valley. The Fisher Center offers outstanding programs Where No Wall to many communities, including the students and faculty of Bard College, and audi- Remains لحيث ﻻ جدار يبقى .ences in the Hudson Valley, New York City, across the country, and around the world Building on a 159-year history as a competitive and innovative undergraduate institu- Donde No tion, Bard is committed to enriching culture, public life, and democratic discourse by training tomorrow’s thought leaders. Queda Ningún Muro an international festival about borders Land Acknowledgment Statement Cocurated by Tania El Khoury and Gideon Lester In the spirit of truth and equity, it is with gratitude and humility that we acknowl- edge that we are gathered on the sacred homelands of the Muheaconneok or Thursday, November 21, through Sunday, November 24, 2019 Mohican people, who are the stewards of this land. -

Bard College Conservatory of Music

BARD COLLEGE CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC Undergraduate Double Degree Graduate Vocal Arts Program Graduate Conducting Program THE BARD CONSERVATORY IS, ABOVE ALL, FEARLESS AND ADVENTUROUS. WE HONOR TRADITION BY LOOKING TO REINVENT IT. WE HONOR OUR STUDENTS BY TREATING THEM AS WHOLE PERSONS, CAPABLE OF MORE THAN THEY IMAGINED. WE BELIEVE IN EXCELLENCE, CURIOSITY, INQUIRY, RISK TAKING, AND COMMUNITY. THE MISSION OF THE BARD COLLEGE CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC IS TO PROVIDE THE BEST POSSIBLE PREPARATION FOR A PERSON DEDICATED TO A LIFE IMMERSED IN THE CREATION AND PERFORMANCE OF MUSIC. Grand Hall, Liszt Academy, Budapest UNDERGRADUATE Overview The unique undergraduate curriculum of the Bard College Conservatory of Music is guided by the principle that musicians DOUBLE DEGREE should be broadly educated in the liberal arts and sciences to achieve their greatest potential. The five-year, double-degree program combines rigorous Conservatory training with a challenging and comprehensive liberal arts program. All Conservatory students pursue a double degree in a thoroughly integrated program and supportive educational community. Graduating students receive a bachelor of music (B.Mus.) and a bachelor of arts in a field other than music (B.A.). At the Bard Conservatory the serious study of music goes hand in hand with the education of the whole person. 2 UNDERGRADUATE DOUBLE DEGREE bard.edu/conservatory/undergraduate 3 Outstanding Faculty The strength of the Conservatory is in its outstanding faculty— renowned performing musicians whose artistry is featured in the world’s great concert halls and in the teaching studio. They are deeply committed to the individual growth of their students through on-campus weekly lessons, chamber music coachings, and studio classes. -

Felix Mendelssohn Overture in C Major, Op. 101, “Trumpet” Felix Mendelssohn Was Born in Hamburg in 1809 and Died in Leipzig in 1847

Felix Mendelssohn Overture in C major, Op. 101, “Trumpet” Felix Mendelssohn was born in Hamburg in 1809 and died in Leipzig in 1847. He composed this work in 1826. The circumstances of its first performance are unknown, though it may have been first heard with a performance of Handel’s Israel in Egypt led by the composer in Düsseldorf the same year. Mendelssohn revised the work in 1833. The Overture is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings. Mendelssohn composed this work at the age of sixteen, just before he wrote his miraculous Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Some think it was a preliminary study for that masterpiece. If it was, it was not slavishly followed. The subtitle “Trumpet” comes from Mendelssohn’s family always referring to the piece as the “Trumpet Overture,” though hearing the relatively minor role of the trumpets in the work makes one wonder how it came about. Some point to the trumpets’ appearance to punctuate all the major divisions of the work; for others, the prominent interval of the third in the trumpet parts leads to harmonic relationships of a third in the development, but that is getting rather deep into the weeds. In any case, the sixteen year-old Mendelssohn was already a better composer than many ever become, and the Overture is typically brilliant. Mendelssohn himself didn’t think much of it, but it was his father’s favorite work! Concerto for Violin & Orchestra in E minor, Op. 64 Mendelssohn completed his Violin Concerto in 1844, and it was first performed the following year by Ferdinand David, violin, with the Gewandhous Orchestra, Leipzig conducted by Niels Gade. -

Fiery Nielsen Sparks Nordic Opener from Chicago Philharmonic by Lawrence A

Fiery Nielsen sparks Nordic opener from Chicago Philharmonic By Lawrence A. Johnson Mon Sep 22, 2014 at 11:52 am One could put together a notably adventurous season just by combining the repertory of Chicago’s top suburban orchestras. The fact that most offer consistently excellent playing as well as thought- provoking programs makes musical excursions outside the city even more essential. The Chicago Philharmonic opened its 25th anniversary season Sunday night with a “Nordic” program of intriguing yet accessible rarities that could serve as a model of its kind. In its second season under Scott Speck, the orchestra was in characteristic top form with boldly projected and largely polished performances at Pick-Staiger Hall, even if the evening overall proved something of a mixed bag. With partial sponsorship from the Danish embassy, the main works of the evening offered music from the country’s two leading composers, Carl Nielsen and Niels Gade. As Speck noted in his informed and informal verbal notes, Nielsen’s distinctive voice was largely formed even in his earliest works. The Symphony No. 1, written at age 27, showcases Nielsen’s style—the edgy, bustling energy, noodling, rhapsodic wind lines, and vaulting key changes, the First Symphony moving from G minor to C major over its four movements. Nielsen’s first of six works in the genre is a score brimming with confidence, and Speck and the Scott Speck opened the Chicago Philharmonic musicians served up a lively and idiomatic performance, the outer movements Philharmonic’s 25th season with a imbued with ample vitality and swagger. -

Lyric Pieces Janina Fialkowska

GRIEG LYRIC PIECES JANINA FIALKOWSKA PIANO ATMA Classique EDVARD GRIEG I Book | LIVRE 1, op. 12 [EXCERPTS – EXTRAITS] I Book | LIVRE 7, op. 62 [EXCERPTS – EXTRAITS] 1843-1907 1 | No. 1, Arietta [1:20] 14 | No. 1, Sylph (Sylphide) [1:21] 2 | No. 5, Popular melody (Mélodie populaire) [1:26] 15 | No. 4, Brooklet (Ruisseau) [1:28] 16 | No. 6, Homeward (Vers la patrie) [2:51] I Book | LIVRE 2, op. 38 [EXCERPTS – EXTRAITS] I Lyric Pieces 3 | No. 1, Berceuse [3:07] Book | LIVRE 8, op. 65 [EXCERPTS – EXTRAITS] 4 | No. 7, Waltz (Valse) [0:58] 17 | No. 4, Salon [1:57] Pièces lyriques 5 | No. 8, Canon [4:49] 18 | No. 6, Wedding day at Troldhaugen (Jour de Noces à Troldhaugen) [6:32] I Book | LIVRE 3, op. 43 [EXCERPTS – EXTRAITS] I Book | LIVRE 9, op. 68 [EXCERPTS – EXTRAITS] 6 | No. 1, Butterfly (Papillon) [1:33] 19 | No. 3, At your feet (À tes pieds) [3:19] 7 | No. 4, Little bird (Oisillon) [1:40] 20 | No. 4, Evening in the Mountains (Soir dans les montagnes) [3:28] 21 | No. 5, At the Cradle (Au berceau) [2:30] I Book | LIVRE 4, op. 47 [EXCERPTS – EXTRAITS] I 8 | No. 2, Album leaf (Feuille d’album) [4:18] Book | LIVRE 10, op. 71 [EXCERPTS – EXTRAITS] 9 | No. 3, Melody (Mélodie) [3:01] 22 | No. 1, Once upon a time (Il était une fois) [3:49] 10 | No. 4, Norwegian dance (Danse norvégienne) [1:16] 23 | No. 2, Summer’s eve (Soir d’été) [2:24] 24 | No. 3, Puck (Lutin) [1:50] I Book | LIVRE 5, op. -

Merry, Merry, Sarasota!

Robert Vodnoy, Music Director and Conductor Johanna Fincher, soprano Aaron Romm, trumpet Nicholas Arbolino, English horn December 10, 2019, 7:30 p.m. Church of the Redeemer Merry, Merry, Sarasota! Christmas Eve Suite Niels Gade Christmas Cantata Allesandro Scarlatti Siegfried Idyll Richard Wagner Intermission Symphony no. 26 (Lamentations) Joseph Haydn Quiet City Aaron Copland Sandman Song and Evening Song Engelbert Humperdinck Charlie Brown Christmas Vince Guaraldi and George Mendelson/arr. David Pugh White Christmas Irving Berlin/arr. Bruce Chase A Mad Russian Christmas Paul O’Neill, Robert Kinkel, Pyotr Ilych Tchaikovsky/arr. Bob Philips Season Sponsors: Great Music—Great Space Concert Series Funded in part by an Arts and Cultural Alliance of Sarasota County’s Opportunity Grant, powered by the State of the Arts Florida license plates Orchestra Personnel Concertmaster: David Qi—first season playing Concertmaster with the chamber orchestra. David plays violin in the Sarasota Orchestra. Principal Second Violin: Laurie Vodnoy-Wright has been Principal Second Violin since the orchestra’s inception. She is also the orchestra’s Personnel Manager and Librarian. Laurie has performed throughout the United States, Austria and Israel. Violin 1: Margot Zarzycka—first season with the chamber orchestra. Margot plays violin in the Sarasota Orchestra and is a violinist in the Sarasota Bay Arts Piano Trio. Violin 2: Shawna Trost has played in the chamber orchestra since its inception. She plays violin in the Sarasota Orchestra. Principal Viola: Sun-Young Gemma Shin—first season with the chamber orchestra. Sun-Young plays violin in The Venice Symphony Orchestra, and is Associate Concertmaster of the Champaign-Urbana Symphony Orchestra (Illinois). -

Irisjuly 22–31, 2016 the Richard B. Fisher Center

the richard b. fisher center for the performing arts at bard coLLege IRISJULY 22–31, 2016 About The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College Chair Jeanne Donovan Fisher The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, an environment for world-class artistic President Leon Botstein presentation in the Hudson Valley, was designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 2003. Risk- taking performances and provocative programs take place in the 800-seat Sosnoff Theater, presents a proscenium-arch space, and in the 220-seat LUMA Theater, which features a flexible seating configuration. The Center is home to Bard College’s Theater & Performance and Dance Programs, and host to two annual summer festivals: SummerScape, which offers opera, dance, theater, operetta, film, and cabaret; and the Bard Music Festival, which celebrated its 25th year in 2014. Last year’s festival, “Carlos Chávez and His World,” turned for the first time to the music of Mexico and the rest of Latin America. The 2016 festival is devoted to the life and work of Giacomo Puccini. The Center bears the name of the late Richard B. Fisher, former chair of Bard College’s Board of Trustees. This magnificent building is a tribute to his vision and leadership. By Pietro Mascagni The outstanding arts events that take place here would not be possible without the con- Libretto by Luigi Illica tributions made by the Friends of the Fisher Center. We are grateful for their support and IRIS welcome all donations. -

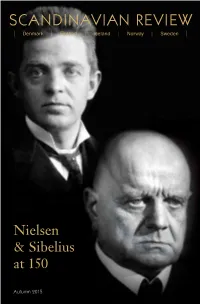

Scandinavian Review Nielsen and Sibelius at 150 Autumn—2015

SCANDINAVIAN REVIEW | Denmark | Finland | Iceland | Norway | Sweden | Nielsen & Sibelius at 150 Autumn 2015 Carl Nielsen Together with Norway’s Jean Sibelius Edvard Grieg, Carl Nielsen and Jean Sibelius are the foremost composers the Nordic countries have ever produced. The two are very different, but they at least share the same year of birth— 1865. NNielsenielsen andand SSibeliusibelius atat 150150 By Daniel M. Grimley YC N M NGER, NGER, A R G RTI / O IELSEN MUSEU GLI A N RL A HE C T PHOTO: 6 SCANDINAVIAN REVIEW AUTUMN 2015 / A. D DE AGOSTINI AUTUMN 2015 SCANDINAVIAN REVIEW 7 Both Nielsen (above) and Sibelius excelled in the field of large-scale orchestral music, but Sibelius (above) and Nielsen first met as students in Berlin in the early 1890s, and remained were equally adept in other genres. friends and colleagues for much of their professional careers. HERE ARE MANY REASONS TO ADMIRE THE LIVES AND WORKS Their strikingly divergent responses to this musical challenge, however, point of the two great Nordic composers, Jean Sibelius and Carl Nielsen, not only to profound differences of political context and cultural geography, Twell beyond celebrating the historical coincidence of their anniversary but also to their respective characters and temperaments. Casting even a year. Few composers can evoke an equivalent sense of time and place with cursory glance at the music of Sibelius and Nielsen is to acknowledge their such vivid intensity. It is difficult to name comparable figures that have been role in a remarkable wave of artistic and intellectual talent in the Nordic so intimately bound up with the formation and promotion of their countries’ region—the “breakthrough” decades of Munch, Strindberg, Gallen-Kallela, musical identities, even if both Nielsen and Sibelius struggled at times with Schjerfbeck, Lagerlöf, Bohr, and others—and to signal their essential impor- the burden that the role of “national composer” inevitably imposed.