Dissertation Final Draft V6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward a QQ Meaningful Shavuot

B”H Q Toward a QQ Meaningful ShavuoT A Personal and Spiritual Guide to Shavuot Making Shavuot Relevant EXCLUSIVE FOR SHLUCHIM By Simon Jacobson Author of Toward A Meaningful Life , A Spiritual Guide to Counting the Omer and 60 Days: A Spiritual Guide to the High Holidays 1. whAt iS ShAvUot? Page 2 5. the SiGnificAnce of MAttAn toRAh Page 18 2. MAttAn toRAh Page 4 a. formal giving of the mitzvoth a. what is torah? b. Uniting heaven and earth, spirit b. the general torah structure and matter c. why was the torah given in a desert? c. the 10 commandments d. G-d chose Us, we chose him 3. diffeRent nAMeS of the holidAy Page 12 e. Special role of children as guarantors f. Special role of women 4. lAwS, cUStoMS Page 13 a. Special prayers; torah readings 6. MoRe iMPoRtAnt eventS Page 21 b. Staying up the first night; tikkun King david and Baal Shem tov’s yahrzeits leil Shavuot 7. MAjoR ShAvUot theMeS And inSiGhtS c. Megillat Ruth Page 24 d. eating dairy e. everyone, even newborns, participate 8. SPeciAl SUPPleMent: 250th AnniveRSARy in hearing the 10 commandments of BAAl SheM tov’S yAhRzeit lecture/Sermon/class : how the Baal Shem tov changed the world Page 33 loAded with MAteRiAl – excellent for your all-night-Shavuos classes and discussions XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Q whaT iS ShavuoT ? Q in the 23rd chapter of leviticus, the torah instructs: you shall count for yourselves, from the morrow of the Shabbat, from the day on which you bring the raised omer— q seven complete weeks shall there be. -

The Rosh Chodesh Planner Was Designed to Serve As a Resource for Shluchos When Planning Women's Programs. Many Years Ago, When

בס"ד PREFACE The Rosh Chodesh Planner was designed to serve as a resource for shluchos when planning women’s programs. Many years ago, when one of the first shluchim arrived in Pittsburgh, PA, prepared to combat the assimilation of America through hafotzas hamayonos, one of the directives of the Rebbe to the shlucha was that it did not suffice for her to only become involved in her husband’s endeavors, but that she should become involved in her own areas of activities as well. Throughout the years of his nesiyus, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Nesi Dorenu, appreciated and valued the influential role the woman plays as the akeres habayis. This is evident in the many sichos which the Rebbe dedicated specifically to Jewish women and girls worldwide. Involved women are catalysts for involved families and involved communities. Shluchos, therefore, have always dedicated themselves towards reaching a broad spectrum of Jewish women from many affiliations, professions and interests. Programs become educational vehicles, provide networking and outreach opportunities for the participants, and draw them closer in their unified quest for a better and more meaningful tomorrow. Many shluchos have incorporated a schedule of gathering on a monthly basis. Brochures are mailed out at the onset of the year containing the year’s schedule at a glance. Any major event(s) are incorporated as well. This system offers the community an organized and well-planned view of the year’s events. It lets them know what to expect and gives them the ability to plan ahead. In the z’chus of all the positive accomplishments that have been and are continuously generated from women’s programs, may we be worthy of the immediate and complete Geulah. -

The Lubavitcher Rebbe's Topsy-Turvy Sukkah

The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s Topsy-Turvy Sukkah he hallmark of a true sage of the mesorah (tradition) is Rabbi Yosef Bronstein the radical embracement of a Tparadox. On the one hand, the talmid Judaic Studies Faculty, Isaac Breuer College and chacham is completely beholden to Stern College for Women the Torah received from previous generations. But simultaneously, 3 העולם נחשב בעינינו כתוהו וכצל ולכך אמרו /he has the ability and obligation to innovativeness. It was this new )סוכה ב.( צא מדירת קבע ושב בדירת עראי breathe new life into these ancient old philosophy that fueled Chabad’s להורות כי גרים אנחנו עלי ארץ מבלי קבע. sources by offering innovative singular activities in the second half of interpretations and novel theories.1 the twentieth century. Behold, the Torah counselled us that It is the proper balance between The Rebbe’s approach to the mitzvah on Sukkot, which is the end of the days these two poles that allows the talmid of sukkah is a prime example of his of repentance, we should accept upon chacham to stay true to the timeless interpretive method and philosophy. ourselves an exile, so that the entire world mesorah while making the eternal In this essay, I will summarize what will be in our eyes like nothing and like a Torah timely and relevant to the I understand to be his central thesis shadow. And therefore they said (Sukkah people of his generation. regarding the nature of the sukkah and 2a) “leave your permanent dwelling and stay in a temporary dwelling” to This description is perfectly apt for contextualize it within the broader framework of his thought. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES English Department Hasidic Judaism in American Literature by Eva van Loenen Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF YOUR HUMANITIES English Department Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy HASIDIC JUDAISM IN AMERICAN LITERATURE Eva Maria van Loenen This thesis brings together literary texts that portray Hasidic Judaism in Jewish-American literature, predominantly of the 20th and 21st centuries. Although other scholars may have studied Rabbi Nachman, I.B. Singer, Chaim Potok and Pearl Abraham individually, no one has combined their works and examined the depiction of Hasidism through the codes and conventions of different literary genres. Additionally, my research on Judy Brown and Frieda Vizel raises urgent questions about the gendered foundations of Hasidism that are largely elided in the earlier texts. -

676 Beis Moshiach

676:Beis Moshiach 22/12/2008 8:58 AM Page 3 contents YOSEF’S SHABBOS 4 D’var Malchus TWO SHLUCHIM ACHIEVED WHAT 6 4,000 COULD NOT Terror in Bombay | Rabbi Naftali Estulin YOSEF WAS FORGOTTEN IN PRISON, 10 BUT NOT ME Feature | Nosson Avrohom THE LUBAVITCH LIBRARY FROM ALEF 12 THROUGH TAV Hei Teives | Avrohom Reinitz USA ONE OF THE TEKIOS CHILDREN 744 Eastern Parkway 24 Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409 Stories | Sholom Gurary Tel: (718) 778-8000 Fax: (718) 778-0800 [email protected] www.beismoshiach.org A DIAMOND AMONG DIAMOND 30 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: DEALERS M.M. Hendel Terror in Bombay | Nosson Avrohom ENGLISH EDITOR: Boruch Merkur [email protected] MIRACLES BROUGHT THEM CLOSE 32 ASSISTANT EDITOR: Miracle Story | Nosson Avrohom Dr. Aryeh Gotfryd HEBREW EDITOR: Rabbi Sholom Yaakov Chazan [email protected] 9TH EUROPEAN MOSHIACH CONGRESS 36 Beis Moshiach (USPS 012-542) ISSN 1082- A TREMENDOUS SUCCESS 0272 is published weekly, except Jewish News holidays (only once in April and October) for $160.00 in Crown Heights, Brooklyn and in all other places for $180.00 per year (45 issues), by Beis Moshiach, 744 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409. Periodicals postage paid at Brooklyn, NY and additional offices. Postmaster: send address changes to Beis Moshiach 744 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409. Copyright 2008 by Beis Moshiach, Inc. Beis Moshiach is not responsible for the content of the advertisements. 676:Beis Moshiach 22/12/2008 8:58 AM Page 4 d’var malchus prescription for Redemption applies even if the Jewish people observe Shabbos properly only YOSEFS once, being careful about the laws and its details just one time. -

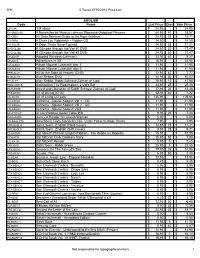

B"H 5 Teves 5775/2014 Price List ENGLISH Code Name List Price

B"H 5 Teves 5775/2014 Price List ENGLISH Code Name List Price Disc Sale Price EO-334I 334 Ideas $ 24.95 $ 24.95 EY-5NOV.SB 5 Novelettes by Marcus Lehman Slipcased (Adopted Princess, $ 64.95 40 $ 38.97 EF-60DA 60 Days Spiritual Guide to the High Holidays $ 24.95 25 $ 18.71 CD-DIRA A Dirah Loy Yisboraich - Yiddish CD $ 14.50 $ 14.50 EO-DOOR A Door That's Never Locked $ 14.95 25 $ 11.21 DVD-GLIM1 A Glimpse through the Veil #1 DVD $ 24.95 30 $ 17.47 DVD-GLIM2 A Glimpse through the Veil #2 DVD $ 24.95 30 $ 17.47 EY-ADOP Adopted Princess (Lehman) $ 13.95 40 $ 8.37 EY-ADVE Adventures in 3D $ 16.95 $ 16.95 CD-ALBU1 Album Nigunei Lubavitch disc 1 $ 11.95 $ 11.95 CD-ALBU2 Album Nigunei Lubavitch disc 2 $ 11.95 $ 11.95 ERR-ALLF All for the Sake of Heaven (CHS) $ 12.95 40 $ 7.77 DVD-ALTE Alter Rebbe, DVD $ 14.95 30 $ 10.47 EY-ALTE Alter Rebbe: Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi $ 19.95 10 $ 17.96 EMO-ANTI.S Anticipating The Redemption, 2 Vol's Set $ 33.95 25 $ 25.46 EAR-ARRE Arrest and Liberation of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi $ 17.95 25 $ 13.46 ETZ-ARTO Art of Giving (CHS) $ 12.95 40 $ 7.77 CD-ARTO Art of Living CD sets $ 125.95 $ 125.95 CD-ASHR1 Ashreinu...Sipurei Kodesh Vol 1 - CD $ 11.95 $ 11.95 CD-ASHR2 Ashreinu...Sipurei Kodesh Vol 2 - CD $ 11.95 $ 11.95 CD-ASHR3 Ashreinu...Sipurei Kodesh Vol3 $ 11.95 $ 11.95 EP-ATOU.P At Our Rebbes' Seder Table P/B $ 9.95 25 $ 7.46 EWO-AURA Aura - A Reader On Jewish Woman $ 5.00 $ 5.00 CD-BAALSTS Baal Shem Tov's Storyteller CD - Uncle Yossi Heritage Series $ 7.95 $ 7.95 EFR-BASI.H Basi L'Gani - English (Hard Cover) -

View Sample of This Item

Praise for Turning Judaism Outward “Wonderfully written as well as intensely thought provoking, Turning Judaism Outward is the most in-depth treatment of the life of the Rebbe ever written. !e author has managed to successfully reconstruct the history of one of the most important Jewish religious leaders of the 20th century, whose life has up to now been shrouded in mystery. A compassionate, engaging biography, this magni"cent work will open up many new avenues of research.” —Dana Evan Kaplan, author, Contemporary American Judaism: Transformation and Renewal; editor, !e Cambridge Companion to American Judaism “In contrast to other recent biographies of the Rebbe, Chaim Miller has availed himself of all the relevant textual sources and archival docu- ments to recount the details of one of the more fascinating religious leaders of the twentieth century. !rough the voice of the author, even the most seemingly trivial aspect of the Rebbe’s life is teeming with interest.... I am con"dent that readers of Miller’s book will derive great pleasure and receive much knowledge from this splendid and compel- ling portrait of the Rebbe.” —Elliot R. Wolfson, Abraham Lieberman Professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, New York University “Only truly great biographers have been able to accomplish what Chaim Miller has with this book... I am awed by his work, and am now even more awed than ever before by the Rebbe’s personality and prodi- gious accomplishments.” —Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb, Executive Vice President Emeritus, Orthodox Union; Editor-in-Chief, Koren-Steinsaltz Talmud “A fascinating account of the life and legacy of a spiritual master. -

Catalog 2020-2021

CATALOG 2020-2021 [1] RABBINICAL COLLEGE OF AMERICA 226 SUSSEX AVENUE MORRISTOWN, NJ 07962-1996 (973) 267-9404 [2] TABLE OF CONTENTS Covid-19 Update ................................................................................... 5 Licensure and Accreditation ................................................................. 5 General Information .............................................................................. 6 Administration ...................................................................................... 7 Faculty .................................................................................................. 7 Availability of Full Time Employee to Assist Enrolled and Prospective Students ................................................................................................ 8 Mission .................................................................................................. 8 The College Campus ............................................................................. 9 Textbook Information ......................................................................... 10 Married Student Housing .................................................................... 10 Dormitory ........................................................................................... 11 History ................................................................................................ 11 Admission Requirements .................................................................... 14 Admission Procedure ......................................................................... -

Imagining the Rebbe: Twoworks in Progress

Kerem 13-allofit-3 4/5/12 1:41 PM Page 101 101 KEREM Imagining the Rebbe: TwoWorks in Progress TWO VERY DIFFERENT IMAGININGS OF RABBI Shneur Zalman of Liadi inspired the two works in progress that follow. Shneur Zalman, also known as the Alter Rebbe ( - ), was the founder of the Chabad movement, the Lubavitch branch of Hasidism. He was widely known not only for his leadership of the Hasidic movement in Lithuania during his lifetime, but also as the author of the Tanya, a master work of Hasidic philosophy and theology. A great-grandson of the mystic and philosopher Rabbi Judah Loew, the “Maharal of Prague,” Shneur Zalman was a prominent disciple of Rabbi Dov Ber of Mezeritch, the “Great Mag - gid,” who was in turn the successor of the founder of Hasidism, the Baal Shem Tov. But Shneur Zalman sought a rational, intellectual basis for Kabbalah and Hasidism, with the “mind ruling over the heart.” Shneur Zalman’s quarrels with the Mitnagdim (opponents of Hasid- ism) and the Gaon of Vilna (Elijah ben Shlomo Zalman, - ) were leg - endary. Starting in , a series of excommunications ( herem ) were launched by the Mitnagdim against the Hasidim; in , the Gaon of Vilna declared the Hasidim heretics and outlawed marriages with Hasidic families. A year after the death of the Gaon in , the leaders of the Vilna Jewish community accused the Hasidim of the subversive activity of supporting the Ottoman Empire. Rabbi Shneur Zalman, who had advocated sending charity to support Jews living in the Ottoman territory of Palestine, was arrested on suspicion of treason and brought to St. -

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the Freevisited Encyclopedi Ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the freevisited encyclopedi ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19 Hasidic Judaism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Sephardic pronunciation: [ħasiˈdut]; Ashkenazic , תודיסח :Hasidic Judaism (from the Hebrew pronunciation: [χaˈsidus]), meaning "piety" (or "loving-kindness"), is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that promotes spirituality through the popularization and internalization of Jewish mysticism as the fundamental aspect of the faith. It was founded in 18th-century Eastern Europe by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov as a reaction against overly legalistic Judaism. His example began the characteristic veneration of leadership in Hasidism as embodiments and intercessors of Divinity for the followers. [1] Contrary to this, Hasidic teachings cherished the sincerity and concealed holiness of the unlettered common folk, and their equality with the scholarly elite. The emphasis on the Immanent Divine presence in everything gave new value to prayer and deeds of kindness, alongside rabbinical supremacy of study, and replaced historical mystical (kabbalistic) and ethical (musar) asceticism and admonishment with Simcha, encouragement, and daily fervor.[2] Hasidism comprises part of contemporary Haredi Judaism, alongside the previous Talmudic Lithuanian-Yeshiva approach and the Sephardi and Mizrahi traditions. Its charismatic mysticism has inspired non-Orthodox Neo-Hasidic thinkers and influenced wider modern Jewish denominations, while its scholarly thought has interested contemporary academic study. Each Hasidic Jews praying in the Hasidic dynasty follows its own principles; thus, Hasidic Judaism is not one movement but a synagogue on Yom Kippur, by collection of separate groups with some commonality. There are approximately 30 larger Hasidic Maurycy Gottlieb groups, and several hundred smaller groups. Though there is no one version of Hasidism, individual Hasidic groups often share with each other underlying philosophy, worship practices, dress (borrowed from local cultures), and songs (borrowed from local cultures). -

Tina Hamrin-Dahl

TINA HAmrin-DAHL This-Worldly and Other-Worldly A Holocaust pilgrimage Pilgrims and the Holocaust Częstochowa is a town known for a shrine to the Black Madonna and every year millions of pilgrims from all over the world come to this Virgin Mary town in south-west Poland. My story is about another kind of pilgrimage, which in a sense is connected to the course of events which occurred in Częstochowa on 22 September 1942. In the morning, the German Captain Degenhardt lined up around 8,000 Jews and commanded them to step either to the left or to the right. This efficient judge from the police force in Leipzig was rapid in his deci- sions and he thus settled the destinies of thousands of people.1 After the Polish Defensive War of 1939, the town (renamed Tschenstochau) had been occupied by Nazi Germany, and incorporated into the General Government. The Nazis marched into Częstochowa on Sunday, 3 September 1939, two days after they invaded Poland. The next day, which became known as Bloody Monday, approximately 150 Jews were shot dead by the Germans. On 9 April 1941, a ghetto for Jews was created. During World War II about 45,000 of the Częstochowa Jews were killed by the Germans; almost the entire Jewish community living there. The late Swedish Professor of Oncology, Jerzy Einhorn (1925–2000), lived in the borderhouse Aleja 14, and heard of the terrible horrors; a ghastliness that was elucidated and concretized by all the stories told around him (Einhorn 2006: 186–9). Jerzy Einhorn survived the ghetto, but was detained at the Hasag-Palcery concentration camp between June 1943 and January 1945.