Integrating the Rational and the Mystical: the Insights and Methods of Three Hassidic̣ Rebbeim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward a QQ Meaningful Shavuot

B”H Q Toward a QQ Meaningful ShavuoT A Personal and Spiritual Guide to Shavuot Making Shavuot Relevant EXCLUSIVE FOR SHLUCHIM By Simon Jacobson Author of Toward A Meaningful Life , A Spiritual Guide to Counting the Omer and 60 Days: A Spiritual Guide to the High Holidays 1. whAt iS ShAvUot? Page 2 5. the SiGnificAnce of MAttAn toRAh Page 18 2. MAttAn toRAh Page 4 a. formal giving of the mitzvoth a. what is torah? b. Uniting heaven and earth, spirit b. the general torah structure and matter c. why was the torah given in a desert? c. the 10 commandments d. G-d chose Us, we chose him 3. diffeRent nAMeS of the holidAy Page 12 e. Special role of children as guarantors f. Special role of women 4. lAwS, cUStoMS Page 13 a. Special prayers; torah readings 6. MoRe iMPoRtAnt eventS Page 21 b. Staying up the first night; tikkun King david and Baal Shem tov’s yahrzeits leil Shavuot 7. MAjoR ShAvUot theMeS And inSiGhtS c. Megillat Ruth Page 24 d. eating dairy e. everyone, even newborns, participate 8. SPeciAl SUPPleMent: 250th AnniveRSARy in hearing the 10 commandments of BAAl SheM tov’S yAhRzeit lecture/Sermon/class : how the Baal Shem tov changed the world Page 33 loAded with MAteRiAl – excellent for your all-night-Shavuos classes and discussions XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Q whaT iS ShavuoT ? Q in the 23rd chapter of leviticus, the torah instructs: you shall count for yourselves, from the morrow of the Shabbat, from the day on which you bring the raised omer— q seven complete weeks shall there be. -

Living the Story About Life in the Midst of the Coronavirus Pesach Guide

ב״ה Wellspringswww.chabadlehighvalley.com Spring 2020/Pesach 5780 DEVORAH’S RECIPE CORNER HOW TO BE Passover CONTAGIOUS ALMOND COOKIES 10 Things I’m Learning Living the Story About Life in the Midst of the Coronavirus Pesach guide A Little Nosh for the Soul Compliments of Chabad of the Lehigh Valley St. Luke’s has been named one of the IBM Watson Health™ 100 Top Hospitals in the Nation. Shana Tova, To learn more visit: stlukes100top.org NOTE FROM THE RABBI Wellsprings Magazine Passover is here... the snow is gone, the weather is turning warmer and the birds are Dedicated to back from their trip to the south. Spring is the Love and in the air! Inspiration of the In Judaism, the proximity of Passover to Lubavitcher springtime is not coincidental. The Torah Rebbe calls Passover “chag ha’aviv” the Holiday of OB”M Spring. In fact, every few years, the Jewish calendar which is lunar-based, is recalibrated to match the solar calendar, for one purpose: to ensure that Passover is in spring. Wellsprings Why spring? The reason is simple, yet profound. While Rosh Ha- shanah marks the beginning of the world’s creation, Passover com- memorates the birth of the Jewish people. For 210 years, the Jewish people were in a womb-like state during the Egyptian servitude. Like a fetus that has all its limbs developed but is unable to control them, our ancestors were living in a suspended state, “a nation within a nation.” And on the 15th of Nissan, they were “born” into freedom. As we celebrate Passover amidst the chirping of the birds and the Editorial flowering of our gardens, we not only remember the birth of the Jewish people 3,300 years ago, but actually re-experience our own Rabbi Yaacov Halperin rebirth. -

Farbrengen Wi Th the Rebbe

פארברענגען התוועדות י״ט כסלו ה׳תשמ״ב עם הרבי Farbrengen wi th the Rebbe english úמי בúימ עו וﬢ ‰ﬧ ו ﬨו ﬨ ר ע ﬨ ˆ ר ﬡ ﬡ י מ נ ו פארברענגען עם הרבי פארברענגען עם הרבי י״ט כסלו תשמ״ב Published and Copyrighted by © VAAD TALMIDEI HATMIMIM HAOLAMI 770 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213 Tel: 718 771 9674 Email: [email protected] VAADHATMIMIM.ORG The Sichos included in this Kovetz are printed with permission of: “Jewish Educational Media” We thank them greatly for this. INDEX Maamar 5 Maamar Padah Beshalom Sicha 1 11 Not the Same Old Story Sicha 2 17 A Voice with No Echo Sicha 3 23 Learning Never Ends Sicha 4 31 Called to Duty Sicha 5 35 Write for yourselves this Song…; Hadran on Minyan Hamitzvos; in honor of the Mivtzah of Ois B’sefer Torah Sicha 6 51 Architects of Peace; Hadran on Maseches Brachos Sicha 7 71 Full time occupation Sicha 8 73 The Road to Peace Sicha 9 87 In Word and in Deed Maamar Maamar Padah Beshalom Peace in our Avodas Hashem Padah Beshalom – peace in our Avodas Hashem. התוועדות י״ט כסלו ה׳תשמ״ב 6 MAAMAR 1. “He delivered my soul in peace from battles against me, because of the many who were with me.” The Alter Rebbe writes in his letter that this verse relates to his liberation, for while reciting this verse, before reciting the following verse, he was notified that he was free. Consequently, many maamarim said on Yud Tes Kislev begin with, and are based on this verse. -

The Soul of a Jew and the Soul of a Non-Jew an Inconvenient Truth and the Search for an Alternative

47 The Soul of a Jew and the Soul of a Non-Jew An Inconvenient Truth and the Search for an Alternative By: HANAN BALK Holiness is not found in the human being in essence unless he sanctifies himself. According to his preparation for holiness, so the fullness comes upon him from on High. A person does not acquire holiness while inside his mother. He is not holy from the womb, but has to labor from the very day he comes into the air of the world. 1 Introduction: The Soul of a Jew is Superior to that of a Non-Jew The view expressed in the above heading—as uncomfortable and racially charged as it may be in the minds of some—was undoubtedly, as we shall show, the prominent position maintained by authorities of Jewish thought throughout the ages, and continues to be so even today. While Jewish mysticism is the source and primary expositor of this theory, it has achieved a ubiquitous presence not only in the writings of Kabbalists,2 but also in the works of thinkers found in the libraries of most observant Jews, who hardly consider themselves followers of Kabbalah. Clearly, for one committed to the Torah and its principles, it is not tenable to presume that so long as he is not a Kabbalist, such a belief need not be a part of his religious worldview. Is there an alternative view that is an equally authentic representation of Jewish thought on the subject? In response to this question, we will 1 R. Simhạ Bunim of Przysukha, Kol Simha,̣ Parshat Miketz, p. -

Jewish Studies Adult Education the Way It Was Meant to Be

The Center for Jewish Studies Adult Education the way it was meant to be Fall Semester 2005 Courses Study Groups Lectures A project of Chabad Women’s Circle Children’s Programs Holidays Prayer Services The Center for Jewish Studies Friends of Lubavitch of Bergen County WELCOME Shalom elcome to The Center for Jewish Studies. Our goal here at Friends of Lubavitch of Bergen County is to provide the most Wcomprehensive, interesting and educational adult Jewish studies program that one can find. We offer courses, which will be a finite number of classes on a certain topic in Judaism; study groups which are ongoing weekly classes that are continuous; and of course our famous lectures where we have scholars, authors and other such Jewish luminaries for an evening of inspiration. Unless otherwise noted, every course, class and lecture is for men and women of all ages and all backgrounds. The courses and classes are geared to both those who have no formal Jewish education and those who have an extensive background - everyone will find each course and class fascinating and worthwhile. We will also be continuing our Chabad Women’s Circle, a hands-on evening with a fascinating lecture, wonderful desserts and much The Center more. This year we have added a Mommy and Me to our many is dedicated to the programs as well, please see page 20 for details. living legacy of The Lubavitcher Feel free to drop in on and sample any course to see if it’s for you, Rebbe, with our “complimentary evening pass.” Rabbi Menachem If you have any questions (on any of the classes or courses) please Mendel Schneerson feel free to call me at 201-907-0686 or e-mail me at [email protected] at anytime. -

UNVERISTY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Spiritual Narrative In

UNVERISTY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Spiritual Narrative in Sound and Structure of Chabad Nigunim A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Zachary Alexander Klein 2019 © Copyright by Zachary Alexander Klein 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Spiritual Narrative in Sound and Structure of Chabad Nigunim by Zachary Alexander Klein Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Richard Dane Danielpour , Co-Chair Professor David Samuel Lefkowitz, Co-Chair In the Chabad-Lubavitch chasidic community, the singing of religious folksongs called nigunim holds a fundamental place in communal and individual life. There is a well-known saying in Chabad circles that while words are the pen of the heart, music is the pen of the soul. The implication of this statement is that music is able to express thoughts and emotions in a deeper way than words could on their own could. In chasidic thought, there are various spiritual narratives that may be expressed through nigunim. These narratives are fundamental in understanding what is being experienced and performed through singing nigunim. At times, the narrative has already been established in Chabad chasidic literature and knowing the particular aspects of this narrative is indispensible in understanding how the nigun unfolds in musical time. ii In other cases, the particular details of this narrative are unknown. In such a case, understanding how melodic construction, mode, ornamentation, and form function to create a musical syntax can inform our understanding of how a nigun can reflect a particular spiritual narrative. This dissertation examines the ways in which musical syntax and spiritual parameters work together to express these various spiritual narratives in sound and structure of nigunim. -

Chapter 51 the Tanya of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, Elucidated by Rabbi Yosef Wineberg Published and Copyrighted by Kehot Publication Society

Chapter 51 The Tanya of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, elucidated by Rabbi Yosef Wineberg Published and copyrighted by Kehot Publication Society « Previous Next » Chapter 50 Chapter 52 The title-page of Tanya tells us that the entire work is based upon the verse (Devarim 30:14), “For this thing (the Torah) is very near to you, in your mouth and in your heart, that you may do it.” And the concluding phrase (“that you may do it”) implies that the ultimate purpose of the entire Torah is the fulfillment of the mitzvot in practice. In order to clarify this, ch. 35 began to explain the purpose of the entire Seder Hishtalshelut (“chain of descent” of spiritual levels from the highest emanation of the Creator down to our physical world), and of man’s serving G‑d. The purpose of both is to bring a revelation of G‑d’s Presence into this lowly world, and to elevate the world spiritually so that it may become a fitting dwelling-place for His Presence. To further explain this, ch. 35 quoted the words of the Yenuka in the Zohar that a Jew should not walk four cubits bareheaded because the Shechinah dwells above his head. This light of the Divine Presence, continues the Zohar, resembles the light of a lamp, where oil and wick are needed for the flame to keep burning. A Jew should therefore be aware, says the Zohar, of the Shechinah above him and keep it supplied with “oil” (good deeds), in order to ensure that the “flame” of the Shechinah keeps its hold on the “wick” (the physical body). -

Essay Question Parsha Inner Dimensions

a project of www.Chabad.org Vayeira 5763 (2002) G-d Revealed Himself to You, How'd You Comment Know It's Him? You're sitting in your room and meditating when you hear a voice. Is it the real thing? Is it another Said the Divine Attribute of of your roommate's pranks? Or just your imagi- nation running wild? How to know? Chessed (love): "As long as Abraham was around, there was Nine, Eleven and Ten nothing for me to do, for he did Essay Where have I heard the numbers 9/11 before? Then my work in my stead." it comes to me. In Sefer Yetzirah, the oldest . Kabbalistic text, a cryptic phrase states: Ten sefirot (Sefer HaBahir) of nothingness; ten and not nine, ten and not eleven People Knocking on my Door Question The mezuzah on our front door seems to act as a beacon that draws charity-seeking individuals to our door at all hours of the evening and night. Frankly, we are considering removing it! Story The Probelm One day, a rich and learned Jew came to one of the great European centers of Torah learning to search for a fitting match for his wise, pious and The Doctor beautiful daughter Why do we go to a doctor? Does a doctor give life? We The Feet We go to the doctor because Inner One way to treat what ails the soul is through the we need to repair not just our head -- talking through the problem. Many are now souls, not just our bodies, but our Dimensions realizing, however, that starting at the other end of world as well. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Visio-Tanya, Ch1, V3.Vsd

The Legend - major new statement, point or idea - key point of the chapter - illustration; paranthetical remark; proving or explanatory comment on the antecedent - reference - logical following, continuation, explanation or reference - justification or proof - juxtaposition of complementary (mutual substitute) or co-existing satements - contrasting of mutually exclusive or contradictory, opposite, incompatible alternatives - connection, with connector A from the previous p age withinh the same chapter A being the antecedent A - connection, with connector A on the next page withinh the same chapter being the successor A ch. 6 - connection, with connector A from chapter 6 being the antecedent A - connection, with connector A in chapter 6 being the successor ch. 6 1 Chapter 1. Structure and Logic. "Be righteous, and be not "And be not wicked; and even if the whole Niddah, wicked in Avot , world tells you that you are 30b your own ch.2.13 righteous, regard yourself as if estimation." you were wicked." A ch.13 If a man considers himself to be wicked he willbe grieved in heart and depressed, and will not be able to serve G-d joyfully and with a content heart; while if he is not perturbed by this, it may lead him to irreverence. "Lord of the universe, Thou It is not preordained Bava hast created righteous men Niddah, A whether a man will be Batra , 16a and Thou hast created 16b ch.14 righteous or wicked. wicked men,..." A There are five types of man: ch.27 righteous man who prospers righteous man who suffers Berachot , wicked man who prospers 7a wicked man who suffers intermediate man The "righteous man who prospers" is the perfect tzaddik ; the "righteous man who suffers" is the imperfect tzaddik . -

Interpreting Diagrams from the Sefer Yetsirah and Its Commentaries 1

NOTES 1 Word and Image in Medieval Kabbalah: Interpreting Diagrams from the Sefer Yetsirah and Its Commentaries 1. The most notorious example of these practices is the popularizing work of Aryeh Kaplan. His critical editions of the SY and the Sefer ha Bahir are some of the most widely read in the field because they provide the texts in Hebrew and English with comprehensive and useful appendices. However, these works are deeply problematic because they dehistoricize the tradi- tion by adding later diagrams to earlier works. For example, in his edition of the SY he appends eighteenth-century diagrams to later versions of this tenth-century text. Popularizers of kabbalah such as Michael Berg of the Kabbalah Centre treat the Zohar as a second-century rabbinic tract without acknowledging textual evidence to the contrary. See his introduction to the Centre’s translation of the Zohar: P. S. Berg. The Essential Zohar. New York: Random House, 2002. 2. For a variety of reasons, kabbalistic works were transmitted in manuscript form long after other works, such as the Hebrew Bible, the Talmud, and their commentaries were widely available in print. This is true in large part because kabbalistic treatises were “private” works, transmitted from teacher to student. Kabbalistic manuscripts were also traditionally transmitted in manuscript form because of their provenance. The Maghreb and other parts of North Africa were important centers of later mystical activity, and print technology came quite late to these regions, with manuscript culture persisting well into the nineteenth, and even into the mid- twentieth century in some regions. -

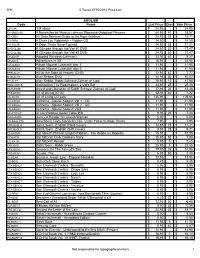

B"H 5 Teves 5775/2014 Price List ENGLISH Code Name List Price

B"H 5 Teves 5775/2014 Price List ENGLISH Code Name List Price Disc Sale Price EO-334I 334 Ideas $ 24.95 $ 24.95 EY-5NOV.SB 5 Novelettes by Marcus Lehman Slipcased (Adopted Princess, $ 64.95 40 $ 38.97 EF-60DA 60 Days Spiritual Guide to the High Holidays $ 24.95 25 $ 18.71 CD-DIRA A Dirah Loy Yisboraich - Yiddish CD $ 14.50 $ 14.50 EO-DOOR A Door That's Never Locked $ 14.95 25 $ 11.21 DVD-GLIM1 A Glimpse through the Veil #1 DVD $ 24.95 30 $ 17.47 DVD-GLIM2 A Glimpse through the Veil #2 DVD $ 24.95 30 $ 17.47 EY-ADOP Adopted Princess (Lehman) $ 13.95 40 $ 8.37 EY-ADVE Adventures in 3D $ 16.95 $ 16.95 CD-ALBU1 Album Nigunei Lubavitch disc 1 $ 11.95 $ 11.95 CD-ALBU2 Album Nigunei Lubavitch disc 2 $ 11.95 $ 11.95 ERR-ALLF All for the Sake of Heaven (CHS) $ 12.95 40 $ 7.77 DVD-ALTE Alter Rebbe, DVD $ 14.95 30 $ 10.47 EY-ALTE Alter Rebbe: Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi $ 19.95 10 $ 17.96 EMO-ANTI.S Anticipating The Redemption, 2 Vol's Set $ 33.95 25 $ 25.46 EAR-ARRE Arrest and Liberation of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi $ 17.95 25 $ 13.46 ETZ-ARTO Art of Giving (CHS) $ 12.95 40 $ 7.77 CD-ARTO Art of Living CD sets $ 125.95 $ 125.95 CD-ASHR1 Ashreinu...Sipurei Kodesh Vol 1 - CD $ 11.95 $ 11.95 CD-ASHR2 Ashreinu...Sipurei Kodesh Vol 2 - CD $ 11.95 $ 11.95 CD-ASHR3 Ashreinu...Sipurei Kodesh Vol3 $ 11.95 $ 11.95 EP-ATOU.P At Our Rebbes' Seder Table P/B $ 9.95 25 $ 7.46 EWO-AURA Aura - A Reader On Jewish Woman $ 5.00 $ 5.00 CD-BAALSTS Baal Shem Tov's Storyteller CD - Uncle Yossi Heritage Series $ 7.95 $ 7.95 EFR-BASI.H Basi L'Gani - English (Hard Cover)