Us Nuclear Testing Enhancing Deterrence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heater Element Specifications Bulletin Number 592

Technical Data Heater Element Specifications Bulletin Number 592 Topic Page Description 2 Heater Element Selection Procedure 2 Index to Heater Element Selection Tables 5 Heater Element Selection Tables 6 Additional Resources These documents contain additional information concerning related products from Rockwell Automation. Resource Description Industrial Automation Wiring and Grounding Guidelines, publication 1770-4.1 Provides general guidelines for installing a Rockwell Automation industrial system. Product Certifications website, http://www.ab.com Provides declarations of conformity, certificates, and other certification details. You can view or download publications at http://www.rockwellautomation.com/literature/. To order paper copies of technical documentation, contact your local Allen-Bradley distributor or Rockwell Automation sales representative. For Application on Bulletin 100/500/609/1200 Line Starters Heater Element Specifications Eutectic Alloy Overload Relay Heater Elements Type J — CLASS 10 Type P — CLASS 20 (Bul. 600 ONLY) Type W — CLASS 20 Type WL — CLASS 30 Note: Heater Element Type W/WL does not currently meet the material Type W Heater Elements restrictions related to EU ROHS Description The following is for motors rated for Continuous Duty: For motors with marked service factor of not less than 1.15, or Overload Relay Class Designation motors with a marked temperature rise not over +40 °C United States Industry Standards (NEMA ICS 2 Part 4) designate an (+104 °F), apply application rules 1 through 3. Apply application overload relay by a class number indicating the maximum time in rules 2 and 3 when the temperature difference does not exceed seconds at which it will trip when carrying a current equal to 600 +10 °C (+18 °F). -

EUROPE RECEPTION T: +1 905-338-0000/ +1 888-901-3090 E: [email protected] CANADIAN DEALERSHIP PRICE 2020 Gvainteriors.Com PRICES ARE in CANADIAN DOLLARS

GVA Interiors, Inc. PRICELIST 2771 Bristol Circle, Oakville, Ontario L6H 6X5 Canada EUROPE RECEPTION T: +1 905-338-0000/ +1 888-901-3090 E: [email protected] CANADIAN DEALERSHIP PRICE 2020 gvainteriors.com PRICES ARE IN CANADIAN DOLLARS CONFIDENTIAL E: [email protected] gvainteriors.com EUROPE RECEPTION *** RECEPTION HEIGHT 1162 MM / 45.7" *** LASEREDGE BANDING TECHNOLOGY *** STRAIGHT LINE INTERMEDIATE RECEPTION DIMENSIONS, INCHES DIMENSIONS, MM PART NUMBER PROJECT PRICE TOP COVER WITHOUT CUT W47.2"D29.6"H45.7" W1200 D752 H1162 193900 $ 1,151.13 a TOP CUTOUT COVER W47.2"D29.6"H45.7" W1200 D752 H1162 193904 $ 1,170.84 a ANGULAR INTERMEDIATE RECEPTION DIMENSIONS, INCHES DIMENSIONS, MM PART NUMBER PROJECT PRICE W47.2"D29.6"H45.7" W1200 D752 H1162 193970 $ 1,025.91 W55.1" D29.6" H45.7" W1400 D752 H1162 193972 $ 1,214.63 a TOP COVER WITHOUT CUT W47.2"D29.6"H45.7" W1200 D752 H1162 193971 $ 1,025.94 W55.1" D29.6" H45.7" W1400 D752 H1162 193973 $ 1,214.63 a DIMENSIONS, INCHES DIMENSIONS, MM PART NUMBER PROJECT PRICE W47.2" D29.6" H45.7" W1200 D752 H1162 193974 $ 1,041.79 W55.1" D29.6" H45.7" W1400 D752 H1162 193976 $ 1,232.69 a TOP CUTOUT COVER W47.2" D29.6" H45.7" W1200 D752 H1162 193975 $ 1,041.79 W55.1" D29.6" H45.7" W1400 D752 H1162 193977 $ 1,232.69 a STRAIGHT LINE END PART RECEPTION DIMENSIONS, INCHES DIMENSIONS, MM PART NUMBER PROJECT PRICE W63" D29.6" H45.7" W1600 D752 H1162 193910 $ 1,457.05 W71" D29.6" H45.7" W1800 D752 H1162 193912 $ 1,614.87 a TOP COVER WITHOUT CUT W63" D29.6" H45.7" W1600 D752 H1162 193911 $ 1,457.05 W71" D29.6" H45.7" W1800 D752 H1162 193913 $ 1,614.87 a DIMENSIONS, INCHES DIMENSIONS, MM PART NUMBER PROJECT PRICE W63" D29.6" H45.7" W1600 D752 H1162 193914 $ 1,477.80 a W71" D29.6" H45.7" W1800 D752 H1162 193916 $ 1,638.04 TOP CUTOUT COVER W63" D29.6" H45.7" W1600 D752 H1162 193915 $ 1,477.80 W71" D29.6" H45.7" W1800 D752 H1162 193917 $ 1,638.04 a GVA Interiors, Inc. -

Experience a Lower Total Cost of Ownership

EXPERIENCE A LOWER TOTAL COST OF OWNERSHIP Timken® Spherical Roller Bearings are engineered to give you more of what you need. Lower Operating Temperatures Rollers are guided by cage pockets—not a center guide ring—eliminating a friction point and resulting in 4–10% less rotational torque and 5ºC lower operating temperatures.* Less rotational torque leads to improved efficiency, lower energy consumption and more savings. Lower temperatures reduce the oil oxidation rate by 50% to extend lubricant life. Tougher Protection Hardened steel cages deliver greater fatigue strength, increased wear resistance and tougher protection against shock and acceleration. Optimized Uptime Unique slots in the cage face improve oil flow and purge more contaminants from the bearing to help extend equipment uptime. Minimized Wear Improved profiles reduce internal stresses and optimize load distribution to minimize wear. Improved Lube Film Enhanced surface finishes avoid metal-to-metal contact to reduce friction and result in improved lube film. Higher Loads Longer rollers result in 4–8% higher load ratings or 14–29% longer predicted bearing life. Higher load ratings enable you to carry heavier loads. Brass Cages Available in all sizes; ready when you need extra strength and durability in the most unrelenting conditions, including extreme shock and vibration, high acceleration forces, and minimal lubrication. Increase your operational efficiencies and extend maintenance intervals. Starting now. Visit Timken.com/spherical to find out more. *All results are from head-to-head -

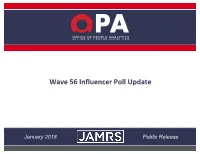

Influencer Poll: Likelihood to Recommend & Support

Wave 56 Influencer Poll Update January 2018 Public Release Influencer Poll: Likelihood to Recommend & Support 1 Likelihood to Recommend and Support Military Service Likelihood to Recommend and Support Military Service 80% 71% 70% 71% 70% 66% 66% 66% 67% 63% 63% 63% 64% 61% 63% 60% 50% 46% 47% 47% 45% 44% 42% 43% 42% 39% 38% 40% 35% 32% 33% 34% 34% 30% 20% 10% Likely to Recommend: % Likely/Very Likely Likely to Support: % Agree/Strongly Agree Yearly Quarterly 0% Jan–Mar 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Likely to Recommend Military Service Likely to Support Decision to Join § Influencers’ likelihood to support the decision to join the Military increased significantly from 67% in 2015 to 70% in 2016. § However, Influencers’ likelihood to support the decision to join the Military remained stable in January–March 2017. = Significantly change from previous poll Source: Military Ad Tracking Study (Influencer Market) Wave 56 2 Questions: q1a–c: “Suppose [relation] came to you for advice about various post-high school options. How likely is it that you would recommend joining a Military Service such as the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, or Coast Guard?” q2ff: “If [relation] told me they were planning to join the Military, I would support their decision.” Likelihood to Recommend Military Service By Influencer Type Likelihood to Recommend Military Service 80% 70% 63% 59% 59% 60% 58% 60% 57% 56% 57% 55% 54% 53% 48% 55% 50% 54% 47% 52% 51% 44% 51% 47% 42% 42% 42% 49% 41% 43% 42% 45% 45% 46% 40% 42% 37% 41% 39% 41% 38% 38% 38% 37% 37% 39% 34% 35% 34% 30% 33% 33% 32% 33% 32% 31% 32% 31% 31% 31% 32% 20% 25% 25% 24% 31% 29% 10% % Likely/Very Likely Yearly Quarterly 0% Jan–Mar 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Fathers Mothers Grandparents Other Influencers § Influencers’ likelihood to recommend military service remained stable in January–March 2017 for all influencer groups. -

Nuclear Weapons: the Reliable Replacement Warhead Program

Order Code RL32929 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Nuclear Weapons: The Reliable Replacement Warhead Program May 24, 2005 Jonathan Medalia Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Nuclear Weapons: The Reliable Replacement Warhead Program Summary Most current U.S. nuclear warheads were built in the 1980s, and are being retained longer than was planned. Yet warheads deteriorate with age, and must be maintained. The current approach monitors them for signs of aging. When problems are found, a Life Extension Program (LEP) rebuilds components. While some can be made to new specifications, a nuclear test moratorium bars that approach for critical components that would require a nuclear test. Instead, LEP rebuilds them as closely as possible to original specifications. Using this approach, the Secretaries of Defense and Energy have certified stockpile safety and reliability for the past nine years without nuclear testing. In the FY2005 Consolidated Appropriations Act, Congress initiated the Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW) program by providing $9 million for it. The program will study developing replacement components for existing weapons, trading off features important in the Cold War, such as high yield and low weight, to gain features more valuable now, such as lower cost, elimination of some hazardous materials, greater ease of manufacture, greater ease of certification without nuclear testing, and increased long-term confidence in the stockpile. It would modify components to make these improvements; in contrast, LEP makes changes mainly to maintain existing weapons. Representative David Hobson, RRW’s prime sponsor, views it as part of a comprehensive plan for the U.S. -

APRIL 2018 SUPPLEMENT PORTFOLIO Inspired by Classic Forms, the Portfolio Collection Adopts Modern Influences to Elevate Casual Silhouettes

APRIL 2018 SUPPLEMENT PORTFOLIO Inspired by classic forms, the Portfolio collection adopts modern influences to elevate casual silhouettes. Deliberate consideration is given to proportion and form, balanced with an unwavering focus on comfort. Rooted in the core of Precedent’s design legacy, these timeless pieces introduce luxury into today’s interior living spaces. 3320-S1 Zelda Sofa 2 PRECEDENT-FURNITURE.COM PRECEDENT-FURNITURE.COM 1 PORTFOLIO 3311-C1 Elaine Chair / W31 D34 H30.5 Seat H17.5 / Arm H25 / Inside Seat W22 D22 Optional Ember finish shown Also available: L3311-C1 Elaine Leather Chair 3318-S1 Halifax Sofa / W87 D39 H37 Seat H20 / Arm H29.5 / Inside Seat W74 D22 Available in Espresso finish only Standard with two toss pillows Also available: L3318-S1 Halifax Leather Sofa 3327-C1 Marion Chair / W32.5 D38 H33.5 Seat H18 / Arm H24.5 / Inside Seat W21 D22 Available in Espresso finish only Also available: L3327-C1 Marion Leather Chair 3320-S1 Zelda Sofa / W90.5 D35.5 H30 Seat H17 / Arm H30 / Inside Seat W78 D23 Optional Ember finish shown Standard with two toss pillows 2 PRECEDENT-FURNITURE.COM PRECEDENT-FURNITURE.COM 3 3278-S1 Rosalyn Sofa (see main catalog, page 26), 229-830 Arles Round Cocktail Table, 3297-C1 Zoey Chair (see main catalog, page 136) 4 PRECEDENT-FURNITURE.COM PRECEDENT-FURNITURE.COM 5 PORTFOLIO 3280 Nicole Series 3282 Hilton Series 3280-SL Nicole Left Arm Sofa / W83.5 D38 H33 3280-CR Nicole Right Arm Chaise / W47 D65 H33 3282-S2 Hilton Sofa / W100 D42 H35 Seat H18 / Arm H22 / Inside Seat W73.5 D22 Seat H18 / Arm -

LUZERNE COUNTY COMMUNITY COLLEGE LIBRARY New Materials July 01, 2015 - September 30, 2015

LUZERNE COUNTY COMMUNITY COLLEGE LIBRARY New Materials July 01, 2015 - September 30, 2015 CIRCULATING MATERIALS BF295 .R45 2014 The relation of childhood physical activity to brain health, cognition, and scholastic achievement. Boston, MA: Wiley, c2014. BF531 .O73 2014 Orians, Gordon H., author. Snakes, sunrises, and Shakespeare: how evolution shapes our loves and fears. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, c2014. BF723.S45 S53 2015 Sleep and development: advancing theory and research. Boston, MA: Wiley, c2015. BL312 .L435 2015 Leeming, David Adams. The handy mythology answer book. Detroit, MI: Visible Ink, c2015. BL504 .S86 2014 Sumegi, Angela. Understanding death: an introduction to ideas of self and the afterlife in world religions. Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell, c2014. BP182 .S74 2015 Stern, Jessica. ISIS: the state of terror. First edition. New York: Ecco Press, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, c2015. BX1378.7 .W55 2015 Wills, Garry. The future of the Catholic Church with Pope Francis. New York: Viking, 2015. CS16 .S646 2010 Smolenyak, Megan. Who do you think you are? : the essential guide to tracing your family history. New York: Penguin Books, c2010. CS21.5 .H465 2014 Hendrickson, Nancy, author. Unofficial Guide to Ancestry.com: How to Find Your Family History on the #1 Genealogy Website. Cincinnati, OH: Family Tree Books, an imprint of F+W Media, Inc., c2014. Luzerne County Community College Library New Materials – July – September 2015 CT120 .W33 2015 Wagman-Geller, Marlene. Behind every great man: the forgotten women behind the world's famous and infamous. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, c2015. D769.8.A6 R43 2015 Reeves, Richard, author. Infamy: the shocking story of the Japanese American internment in World War II. -

Water Volume Index, 1869 - 1906

November 14, 2004 WATER VOLUME INDEX, 1869 - 1906 Name Date Entry Number Name Date Entry Number A B Accounting: Baldwin Creek See: nd W122 Receipts and Expenses Baldwin, Frederick Douglass, Supervisor Agreements 1900 W85 Branciforte 1901 W101 1877 W38-W42 Baldwin, Levi Karner Agreements, Water 1881 W63 Branciforte Ball-cocks 1877 W9-W11,W28-W32,W35-W37,W43- See: W45,W89-W91 Water Valves 1900 W82-W83 Bank of Santa Cruz County 1901 W92,W95,W98-W100 1882 W60 1902 W103-W107,W109-W115 Banks 1904 W117-W118 See: Laguna Bank of Santa Cruz County 1881 W68-W70 Santa Cruz Bank of Savings & Loan Santa Cruz Baptist Churches 1882 W58-W59 See: 1900 W85 Twin Lakes Baptist Assembly 1901 W94,W101 Barns 1902 W102 Branciforte 1904 W116 1877 W40 1906 W119-W121 1901 W98 Soquel Bath Tubs 1901 W96-W97 See: See also: Home Furnishings Water Rights Bay Street Agriculture Santa Cruz See: nd W77,W79 Farms and Agriculture 1888 W13-W14,W19 Alfalfa Ben Lomond Winery See: 1901 W99 Hay 1904 W117 Allardt, George F. Bennett, E.H. [Reverend] 1888 W20 1906 W119 Almstead, Fanny A. [aka Mrs. Leonard T. Berries [Crop] Almstead], Grantor Branciforte 1881 W1-W4,W46-W51 1901 W92 1882 W73-W74 Santa Cruz Almstead, Leonard T. 1900 W81 1881 W62-W63,W68-W69 1906 W121 Almstead, Leonard T., Grantor Bias, William Henry, Clerk 1881 W1-W4,W46-51 1888 W57 1882 W73-74 Blackberries Anthony, Elihu, Grantee See: 1869 W75 Berries Anthony, George Blackburn Dam 1877 W12,W33 1877 W29 Anthony’s Farm Blackburn Gulch 1877 W12,W33 1895 W87 Aqueducts Blackburn Gulch Road See: Branciforte Dams and Flumes 1900 W82 Arana Gulch 1901 W99 1902 W103 1904 W117 Arroyo de la Villa Blaine Street 1869 W75 Santa Cruz 1906 W121 Index: Water Volume F.A. -

Keyword Index

Neuropsychopharmacology (2012) 38, S479–S521 & 2012 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. All rights reserved 0893-133X/12 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org S479 Keyword Index 10b-Hydroxyestra-14-diene-3-one . W87 M114, M115, M116, M119, M123, M130, M131, M132, M134, M140, M142, 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy . W34 M143, M144, M145, M146, M149, M150, M151, M152, M154, M155, M156, M157, M158, M159, M166, M168, M172, M174, M178, M179, M181, M182, 22q11 deletion . T123 M185, M186, M187, M188, M193, M197, M198, M199, M200, M201, M202, 2-AG . .23.2, 23.3, M145, T69, T161 M205, M212, T3, T5, T8, T13, T16, T17, T20, T22, T24, T25, T27, T31, T35, 3-MT . M182 T44, T49, T51, T58, T60, T66, T67, T72, T75, T77, T79, T80, T82, T83, T86, T88, T91, T95, T98, T99, T103, T109, T111, T113, T114, T116, T117, T119, 5-HT . 14.2, 17.4, 44.2, 52, M19, M45, M64, M72, M75, M91, T121, T125, T126, T128, T138, T140, T144, T147, T148, T151, T153, T154, M115, M144, M147, M154, M157, M161, M162, M183, M185, M186, T17, T49, T158, T161, T166, T167, T171, T173, T176, T177, T179, T181, T185, T188, T53, T120, T163, T194, W54, W125, W165, W176, W191 T189, T192, T194, T197, T198, T202, T203, T209, T210, W3, W5, W8, W10, 5-HT6 . .W125 W18, W20, W31, W32, W45, W46, W53, W54, W57, W64, W71, W72, W75, W76, W81, W83, W84, W87, W93, W94, W97, W100, W103, W104, W105, A W106, W107, W115, W116, W117, W118, W120, W124, W129, W137, W138, W143, W154, W158, W159, W160, W169, W172, W173, W176, W177, W186, W188, W195, W197, W199, W201, W203, W208, W214, W218 AAV . -

The Reliable Replacement Warhead Program: Background and Current Developments

Order Code RL32929 The Reliable Replacement Warhead Program: Background and Current Developments Updated June 16, 2008 Jonathan Medalia Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division The Reliable Replacement Warhead Program: Background and Current Developments Summary Most current U.S. nuclear warheads were built in the 1970s and 1980s and are being retained longer than was planned. Yet they deteriorate and must be maintained. To correct problems, a Life Extension Program (LEP), part of a larger Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP), replaces components. Modifying some components would require a nuclear test, but the United States has observed a test moratorium since 1992. Congress and the Administration prefer to avoid a return to testing, so LEP rebuilds these components as closely as possible to original specifications. With this approach, the Secretaries of Defense and Energy have certified stockpile safety and reliability for the past 12 years without nuclear testing. The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), which operates the U.S. nuclear weapons program, would develop the Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW). For FY2005, Congress provided an unrequested $9.0 million to start RRW. The FY2006 RRW appropriation was $24.8 million, the FY2007 operating plan had $35.8 million, and the FY2008 request was $88.8 million for NNSA and $30.0 million for the Navy. The Department of Defense Appropriations Act, P.L. 110-116, included $15.0 million for the Navy for RRW. The FY2008 Consolidated Appropriations Act, P.L. 110-161, provided no NNSA funds for RRW. For FY2009, DOE requests $10.0 million for RRW. The Navy requests $23.3 million for RRW but says its request was prepared before Congress eliminated NNSA RRW funds and that the Navy funds would not be used for RRW. -

Formerly Restricted Data Declassification Working Group

OFFICE OF THE UNDERSECRETARY OF DEFENSE FOR INTELLIGENCE Formerly Restricted Data Declassification Working Group USD(I), DUSD I&S October 11, 2016 SECURITY POLICY & OVERSIGHT DIVISION OFFICE OF THE UNDERSECRETARY OF DEFENSE FOR COUNTERINTELLIGENCECOUNTERINTELLIGENCE INTELLIGENCEPUT TEXT FIELD HEREFIELD ACTIVITY ACTIVITY Agenda • Formerly Restricted Data (FRD) Examples • Decision-Making Process • Actions Overview • Website Information / Declassification • Pending Decision Tracker • Declined Declassification Actions • Way Ahead • Questions SECURITY POLICY & OVERSIGHT DIVISION Back to front exit OFFICE OF THE UNDERSECRETARY OF DEFENSE FOR COUNTERINTELLIGENCECOUNTERINTELLIGENCE INTELLIGENCEPUT TEXT FIELD HEREFIELD ACTIVITY ACTIVITY FRD Examples • Stockpile Size and Subcategory Numbers-unless properly declassified by joint DoD/DOE determination • Locations of Weapons Current and Past • Including numbers and types at locations – with some exceptions • Past CONUS locations Unclassified unless co-located with current location-current locations classified with some exceptions • Fact that weapons are/were in NATO, Germany and UK is unclassified unless specific location is given • Any specified OCONUS location (current or past) to include country other than Germany or the UK remain classified • Yields (some have been declassified i.e. the W53) • Circular Error Probability (CEP) • Some Above Ground and Underground Test Results SECURITY POLICY & OVERSIGHT DIVISION Back to front exit3 OFFICE OF THE UNDERSECRETARY OF DEFENSE FOR COUNTERINTELLIGENCECOUNTERINTELLIGENCE -

Keyword Index

Neuropsychopharmacology (2013) 38, S628–S653 & 2013 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. All rights reserved 0893-133X/13 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Keyword Index 17b-estradiol . w224, W137, W14, W156, W158, W162, W165, W171, W174, W177, 2-AG.......................................... W161, W178 W18, W186, W189, W195, W198, W199, W2, W204, W206, W211, W218, W224, W225, W230, W233, W235, 31PMRS............................................M169 W236, W24, W43, W45, W56, W65, W69, W72, W74, 5-HT1A. .M47, T142, T147, W185, W189, W202, W93 W80, W81, W88, W93 5-HT2A. 42.4, W185, W204, W215, W216, W220, W93 acute effects. 55.3, T152, T157, W49 5-HT3 receptor . M209 acute stress . 26.4, T208, T26, T63, T87, W230 5-HT4 receptor . .M192 acute treatment . .T160, T225, W148, W150, W19 5-HTTLPR. M17, W59, W60 adaptive mechanisms . .W159, W219 5ht............................................... W100 ADAR.............................................. W95 5HT-7..............................................W130 addiction. 6.4, 14.1, 28.1, 28.2, 29.1, 29.2, 29.3, 30.1, 5HT2c..............................................W217 30.2, 36.4, 37.1, 37.3, 39.4, 41.3, 42.3, 47.3, 54.4, 55.3, M105, M106, M11, AAV2/5 . T71 M12, M123, M13, M131, M135, M139, M152, M158, M16, Abeta . M83, T144 M163, M164, M168, M198, M203, M217, M218, M226, abstinence . .28.3, 29.2, 29.3, 37.1, 37.3, 38.1, 38.2, 38.3, M229, M231, M234, M36, M50, M82, T10, T114, T125, 45.1, 47.1, M116, M12, M123, M158, M199, M51, M82, T170, T126, T130, T133, T16, T168, T215, T216, T28, T3, T41, T44, T197, T215, T41, W110, W111, W173, W204, W217, W49, T56, T68, T71, T72, T76, T98, W104, W118, W145, W152, W52, W60, W98 W153, W171, W179, W181, W194, W200, W211, W213, abuse .