An Interview with David Zussman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prime Ministers

Board of Directors 25TH ANNUAL TESTIMONIAL DINNER Chair Larry Murray Vice Admiral (Ret’d) & HONOURING CANADA’s former Deputy Minister Ian Bird President and CEO Community Foundations of Canada PRIME MINISTERS Francine Blackburn Canada’s Public Policy Forum pays tribute to our living former Prime Ministers Executive Vice President, Regulatory & Corporate Affairs and the role of the highest office in Canada’s system of governance. RBC Ken Delaney Former Executive Assistant to the National Director of the Steelworkers Union Richard Dicerni Deputy Minister Industry Canada Bruce Drysdale Principal Drysdale-Forstner-Hamilton Public Affairs Doug Emsley President Emsley & Associates Inc. The Right Hon. The Right Hon. The Right Hon. Judy Fairburn Paul Martin Jean Chrétien Kim Campbell Executive Vice-President Environment and Strategic Planning, Cenovus Energy Anne-Marie Hubert Managing Partner, Advisory Services Ernst & Young LLP Marcel Lauzière President & CEO Imagine Canada Mark Lievonen President Sanofi Pasteur Ltd. David J. Mitchell The Right Hon. The Right Hon. The Right Hon. President and CEO Brian Mulroney John Turner Joseph Clark Public Policy Forum Karen Oldfield President & CEO The 25th Annual Testimonial Dinner will take place on The Public Policy Forum is an independent, not-for-profit organization Halifax Port Authority May 3, 2012 at the Metro Toronto Convention Centre. dedicated to improving the quality of government in Canada through Stephen J. Toope enhanced dialogue among the public, private and voluntary sectors. President and Vice-Chancellor For additional information or to purchase a table of tickets: At the Forum we believe that good government, robust public policy University of British Columbia Kelly Cyr 613-238-7858 x248 [email protected] and strong democratic institutions depend on the contributions of all Ilse Treurnicht sectors of society. -

Hershell Ezrin Fonds University of Toronto Archives B2017-0021

University of Toronto Archives and Records Management Services Hershell E. Ezrin fonds B2017-0021 Daniela Ansovini, 2018 © University of Toronto Archives and Records Management Services 2018 Hershell Ezrin fonds University of Toronto Archives B2017-0021 Contents Biographical note ..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and content ................................................................................................................... 4 Series 1: Personal and biographical....................................................................................... 6 Series 2: Correspondence ....................................................................................................... 7 Series 3: Addresses and presentations .................................................................................. 7 Series 4: Professional activity ................................................................................................... 8 Series 5: Photographs ............................................................................................................... 8 Series 6: Editorial cartoons ....................................................................................................... 9 Series 7: Collected bibliographic material............................................................................ 9 Appendix ................................................................................................................................ -

Towards Guidelines on Government Formation Facilitating Openness & Efficiency in Canada’S Governance

Towards Guidelines on Government Formation Facilitating Openness & Efficiency in Canada’s Governance Final Report April 2012 ppforum.ca The Public Policy Forum is an independent, not-for-profit organization dedicated to improving the quality of government in Canada through enhanced dialogue among the public, private and voluntary sectors. The Forum’s members, drawn from business, federal, provincial and territorial governments, the voluntary sector and organized labour, share a belief that an efficient and effective public service is important in ensuring Canada’s competitiveness abroad and quality of life at home. Established in 1987, the Forum has earned a reputation as a trusted, nonpartisan facilitator, capable of bringing together a wide range of stakeholders in productive dialogue. Its research program provides a neutral base to inform collective decision making. By promoting information sharing and greater links between governments and other sectors, the Forum helps ensure public policy in our country is dynamic, coordinated and responsive to future challenges and opportunities. © 2012, Public Policy Forum 1405-130 Albert St. Ottawa, ON K1P 5G4 Tel: (613) 238-7160 Fax: (613) 238-7990 www.ppforum.ca ISBN: 978-1-927009-30-7 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations for Guidelines on Government Formation ....................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... -

Diversification Not Dependence a Made-In-Canada China Strategy

DIVERSIFICATION NOT DEPENDENCE A MADE-IN-CANADA CHINA STRATEGY OCTOBER 2018 ABOUT PPF Good Policy. Better Canada. The Public Policy Forum builds bridges among diverse participants in the policy-making process and gives them a platform to examine issues, offer new perspectives and feed fresh ideas into critical policy discussions. We believe good policy is essential to making a better Canada—a country that’s cohesive, prosperous and secure. We contribute by: Conducting research on key issues Convening candid dialogues on research subjects Recognizing exceptional policy leaders Our approach—called Inclusion to Conclusion—brings emerging and established voices to policy conversations in an effort to inform policy-makers and identify policy options and obstacles. PPF is an independent, non-partisan think tank with a diverse membership drawn from private, public, academic and non-profit organizations. © 2018, Public Policy Forum 1400 - 130 Albert Street Ottawa, ON, Canada, K1P 5G4 613.238.7858 ppforum.ca @ppforumca ISBN: 978-1-988886-32-9 TABLE OF CONTENTS Canada and China: The Way Forward .................................................................................................6 Recommendations ....................................................................................................................................19 The Public Opinion Environment .........................................................................................................29 What We Heard ..................................................................................................................................36 -

PUBLIC POLICY FORUM JANUARY 2017 the SHATTERED MIRROR News, Democracy and Trust in the Digital Age About the Public Policy Forum

PUBLIC POLICY FORUM JANUARY 2017 THE SHATTERED MIRROR News, Democracy and Trust in the Digital Age About the Public Policy Forum The Public Policy Forum works with all levels of government and the public service, the private sector, labour, post-secondary institutions, NGOs and Indigenous groups to improve policy outcomes for Canadians. As a non-partisan, member-based organization, we work from “inclusion to conclusion,” by convening discussions on fundamental policy issues and by identifying new options and paths forward. For 30 years, the Public Policy Forum has broken down barriers among sectors, contributing to meaningful change that builds a better Canada. © 2017, Public Policy Forum Public Policy Forum 1400 - 130, Albert Street Ottawa, ON, Canada, K1P 5G4 Tel/Tél: 613.238.7160 www.ppforum.ca @ppforumca ISBN 978-1-927009-86-4 Table of Contents 2 Introduction 12 Section 1: Diagnostics 36 Section 2: News and Democracy 70 Section 3: What We Heard Section 4: Conclusions 80 and Recommendations Some Final Thoughts 95 Moving Forward 100 Afterword by Edward Greenspon 102 Acknowledgements In a land of bubblegum forests and lollipop trees, every man would have his own newspaper or broadcasting station, devoted exclusively to programming that man’s opinions and perceptions. The Uncertain Mirror, 1970 The Shattered Mirror: News, Democracy and Trust in the Digital Age When he made this fanciful remark in his landmark The Internet, whose fresh and diverse tributaries of report on the state of the mass media in this country, information made it a historic force for openness, now Senator Keith Davey was being facetious, not has been polluted by the runoff of lies, hate and the prophetic. -

Public Service in the Digital Age

www.policymagazine.ca July – August 2015 Canadian Politics and Public Policy Public Service in the Digital Age $6.95 Volume 3 – Issue 4 P3 Building a Better Tomorrow in Canada From railroads and highways to athletes’ villages, BMO® has been helping Canada grow for nearly two centuries. As a pioneer and thought leader in public-private partnerships and the P3 model, BMO Capital Markets brings a wide-range of products and proven execution knowledge to infrastructure clients, uniquely positioning BMO to excel for the next hundred years. BMO Capital Markets is a trade name used by BMO Financial Group for the wholesale banking businesses of Bank of Montreal, BMO Harris Bank N.A. (member FDIC), Bank of Montreal Ireland p.l.c, and Bank of Montreal (China) Co. Ltd and the institutional broker dealer businesses of BMO Capital Markets Corp. (Member SIPC) and BMO Capital Markets GKST Inc. (Member SIPC) in the U.S., BMO Nesbitt Burns Inc. (Member Canadian Investor Protection Fund) in Canada and Asia, BMO Capital Markets Limited (authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority) in Europe and Australia and BMO Advisors Private Limited in India.“Nesbitt Burns” is a registered trademark of BMO Nesbitt Burns Corporation Limited, used under license. “BMO Capital Markets” is a trademark of Bank of Montreal, used under license. “BMO (M-Bar roundel symbol)” is a registered trademark of Bank of Montreal, used under license. ® Registered trademark of Bank of Montreal in the United States, Canada and elsewhere. 14-2175 P3 Infrastructure Ads_Print_Ev5(3).indd 1 2014-10-17 3:09 PM MY LIFE is to be active MY MEDICINE is my hope I was born with hemophilia and have received many blood transfusions. -

Hard Choices

A MACDONALD-LAURIER INSTITUTE PUBLICATION October 2020 HARD CHOICES Why Canada needs a cohesive, consistent strategy towards Communist China August 2020 Andrew Pickford and Jerey F. Collins Board of Directors Advisory Council Research Advisory Board CHAIR John Beck Pierre Casgrain President and CEO, Aecon Enterprises Janet Ajzenstat Director and Corporate Secretary, Inc., Toronto Professor Emeritus of Politics, Casgrain & Company Limited, McMaster University Montreal Erin Chutter Executive Chair, Global Energy Metals Brian Ferguson VICE-CHAIR Corporation, Vancouver Professor, Health Care Economics, Laura Jones University of Guelph Executive Vice-President of the Navjeet (Bob) Dhillon Canadian Federation of Independent President and CEO, Mainstreet Equity Jack Granatstein Business, Vancouver Corp., Calgary Historian and former head of the Canadian War Museum Jim Dinning MANAGING DIRECTOR Patrick James Brian Lee Crowley, Ottawa Former Treasurer of Alberta, Calgary Dornsife Dean’s Professor, SECRETARY David Emerson University of Southern California Corporate Director, Vancouver Vaughn MacLellan Rainer Knopff DLA Piper (Canada) LLP, Toronto Richard Fadden Professor Emeritus of Politics, TREASURER Former National Security Advisor to the University of Calgary Martin MacKinnon Prime Minister, Ottawa Larry Martin Co-Founder and CEO, B4checkin, Brian Flemming Principal, Dr. Larry Martin and Halifax International lawyer, writer, and policy Associates and Partner, DIRECTORS advisor, Halifax Agri-Food Management Excellence, Wayne Critchley Robert -

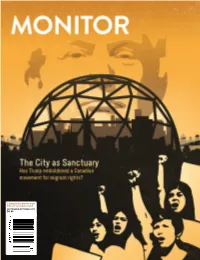

CCPA Monitor

CANADIAN CENTRE FOR POLICY ALTERNATIVES SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017 $6.95 Contributors Richard Nimijean is a member of the School of Raymond Biesinger is Indigenous and Canadian an illustrator and artist Studies at Carleton University based in Montreal. He likes in Ottawa. concepts, making music, politics, Instagram, 19th- Aditya Rao is an organizer Vol. 24, No. 3 century bird’s-eye-view with the Ottawa Sanctuary Book reviews in the ISSN 1198-497X panoramic maps, and a mix of City Network, and is in his Monitor are co-ordinated Canada Post Publication 40009942 minimalism and maximalism. final year of a joint JD and by Octopus Books, a The Monitor is published six times MA program at the University community-owned anti- Remie Geoffroi has been a a year by the Canadian Centre for of Ottawa’s faculty of law oppressive bookstore in full-time freelance illustrator Policy Alternatives. and Carleton University’s Ottawa. since 2001. His clients The opinions expressed in the Norman Paterson School include major publications Monitor are those of the authors of International Affairs, such as the Wall Street and do not necessarily reflect specializing in the law of Journal, Hollywood Reporter, the views of the CCPA. forced migration. He has ESPN, Wired, Billboard and Please send feedback to been active in refugee and New York magazine. Remie [email protected]. migrant rights organizing for recently illustrated the latest a decade. Editor: Stuart Trew book from New York Times Senior Designer: Tim Scarth best-selling author Tim Gillian Steward is a Calgary- Layout: Susan Purtell Toronto Editorial Board: Peter Bleyer, Ferriss, entitled Tool of Titans. -

Peter Mansbridge

www.policymagazine.ca July—August 2019 Canadian Politics and Public Policy The Canadian Idea $6.95 Volume 7—Issue 4 On On June 6, 1919, CN was created by an act of the Parliament of Canada. This year, we celebrate 100 years on the move. It took the best employees, retirees, customers, partners Track and neighbouring communities to make us a world leader in transportation. For our first 100 years and the next 100, we say thank you. for 100 cn.ca Years CNC_191045_CN100_Policy_Magazine.indd 1 19-06-14 10:45 dossier : CNC-191045 client : CN date/modif. rédaction relecture D.A. épreuve à description : EN ad Juin 100% titre : CN & Aboriginal Communities 1 sc/client infographe production couleur(s) publication : On Track for 100 Years 14/06/19 format : 8,5" x 11" infographe : CM 4c 358, rue Beaubien Ouest, bureau 500 Montréal (Québec) H2V 4S6 t 514 285-1414 PDF/X-1a:2003 Love moving Canada in the right direction Together, we’re leading Canadians towards a more sustainable future We’re always We’re committed We help grow We’re connecting connected to the environment the economy communities With free Wi-Fi, phone charging Where next is up to all of us. Maximizing taxpayer We are connecting more than outlets and roomy seats, Making smart choices today value is good for 400 communities across the you’re in for a comfy ride will contribute to a greener your bottom line country by bringing some (and a productive one, too). tomorrow. (and Canada’s too). 4,8 million Canadians closer to the people and places they love. -

The Government of Canada's Experience Eliminating the Deficit

Program Review: The Government of Canada’s Experience Eliminating the Deficit, 1994-1999 A Canadian Case Study Jocelyne Bourgon, P.C., O.C. Addressing International Governance Challenges The Centre for International Governance Innovation Table of Contents Summary Summary 2 Many governments relying on increased spending financed by large deficits to pull their countries out of recession will eventu- Introduction 2 ally face the challenge of restoring fiscal stability. Based exclusive- About the Author 3 ly on publicly available information, this report looks at the path Growth, Prosperity, Deficits and 3 the Government of Canada followed to improve the health of its Debts: 1975 - 1984 public finances in the mid-1990s. Over a three-year period (1994- Stagflation 1997), Canada eliminated a sizable budgetary deficit. By 1998-99, Canada Pursues a Divergent Course all Program Review decisions were implemented. Canada ran consecutive surpluses until 2007-08. The report reviews histori- Learning from the Past: 1975 - 1984 cal financial data and examines the Program Review exercise of Changing Course: 1984 - 1993 8 the mid-1990s, describing its development, process, methodology An Early Attempt and machinery. It provides an overview of the main results and Making Progress – Not Enough identifies lessons learned that may be of durable value in Canada and Not Fast Enough and of interest to other countries as they work to restore fiscal Structural Reform and Agenda stability in the future. Overload Learning from the Past: 1984 - 1993 Regaining Canada’s Fiscal Sovereign- 13 Introduction ty: 1993 - 1999 The Approach Governments around the world have made many attempts to The Scope eliminate their deficits and reduce their debt. -

ED475453.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 475 453 CE 084 822 AUTHOR Wyman, Miriam; Shulman, David; Ham, Laurie TITLE Learning to Engage: Experiences with Civic Engagement in Canada. INSTITUTION Canadian Policy Research Networks Inc., Ottawa (Ontario). PUB DATE 2000-08-00 NOTE 106p.; Part of an international research effort by the Commonwealth Foundation. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.cprn.com/docs/corporate/ lte_e.pdf. PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Activism; Adult Education; *Citizen Participation; *Citizen Role; *Citizenship Responsibility; Community Education; Community Involvement; Democracy; Global Education; *Government Role; Political Attitudes; *Social Change; Trust (Psychology) IDENTIFIERS Canada; *Government Citizen Relationship ABSTRACT This report explores questions about roles for citizens and governments in a good society by examining six Canadian experiences with civic engagement. Each case study involves different sectors of society, key players, goals, processes, and outcomes; touches on long-standing policy issues, in Canada; and, details how players have come together or failed to engage one another and work toward finding creative solutions to often overwhelming and complex policy situations. Many experiences highlight obstacles to a trusting relationship between government and citizens, while pointing to steps that citizens and governments can take to recreate their relationship and allow for meaningful, mutual engagement. None of the case studies provide a neatly packaged outcome. They involve these three kinds of situations: government-initiated engagement (immigration review, National Forum on Health); citizen-initiated engagement (Sydney Tar Ponds, Nunavut); and citizens in the global arena (Multilateral Agreement on Investment, regulating. financial services). Following each case study, questions regarding effective engagement are explored. -

G1613-B Repro English Text

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. Public Policy Issues and the Oliphant Commission The independent research studies in this volume reflect the views of their authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Commission or the Commissioner. Public Policy Issues and the Oliphant Commission Independent Research Studies Prepared for Commission of Inquiry into Certain Allegations Respecting Business and Financial Dealings Between Karlheinz Schreiber and the Right Honourable Brian Mulroney Craig Forcese Director of Research © Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2010 Cat.