A Genus-Level Phylogenetic Linear Sequence of Monocots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beginner's Guide to Bromeliad Names by Derek Butcher May 2015

Beginner’s Guide to Bromeliad Names by Derek Butcher May 2015 This is a general look at Bromeliad names because, as in life, there are always exceptions to the rule! First let us look at plants found in the wild which Botanists are interested in and which are given two Latin names. One is the genus – or surname and the other is the species name - or given name. Plants have been given these names for some 300 years and there has been duplication and different interpretation which means that various botanists over the years have changed names and also have relegated some names to what we call synonymy. See The New Bromeliad Taxon List at: http://botu07.bio.uu.nl/bcg/taxonList.php This is a list of what I have recorded and the current name is in bold letters. If a botanists name is in brackets it means that he gave the original species name but someone later has changed the genus name. 1 Whenever a new species is named you should have a herbarium specimen or equivalent and a written description. A couple of examples of species: (note the bold black writing in The New Bromeliad Taxon List) Acanthostachys pitcairnioides Acanthostachys strobilacea Jose Donayre 2 Now to a plant you should be familiar with - Aechmea fasciata and how the botanist sees it. You may first see the old names that have been used in the past. But let us concentrate on the bold black. You may have plants with two of the names but what about the other two. -

Partial Flora Survey Rottnest Island Golf Course

PARTIAL FLORA SURVEY ROTTNEST ISLAND GOLF COURSE Prepared by Marion Timms Commencing 1 st Fairway travelling to 2 nd – 11 th left hand side Family Botanical Name Common Name Mimosaceae Acacia rostellifera Summer scented wattle Dasypogonaceae Acanthocarpus preissii Prickle lily Apocynaceae Alyxia Buxifolia Dysentry bush Casuarinacea Casuarina obesa Swamp sheoak Cupressaceae Callitris preissii Rottnest Is. Pine Chenopodiaceae Halosarcia indica supsp. Bidens Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia blackiana Samphire Chenopodiaceae Threlkeldia diffusa Coast bonefruit Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia quinqueflora Beaded samphire Chenopodiaceae Suada australis Seablite Chenopodiaceae Atriplex isatidea Coast saltbush Poaceae Sporabolis virginicus Marine couch Myrtaceae Melaleuca lanceolata Rottnest Is. Teatree Pittosporaceae Pittosporum phylliraeoides Weeping pittosporum Poaceae Stipa flavescens Tussock grass 2nd – 11 th Fairway Family Botanical Name Common Name Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia quinqueflora Beaded samphire Chenopodiaceae Atriplex isatidea Coast saltbush Cyperaceae Gahnia trifida Coast sword sedge Pittosporaceae Pittosporum phyliraeoides Weeping pittosporum Myrtaceae Melaleuca lanceolata Rottnest Is. Teatree Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia blackiana Samphire Central drainage wetland commencing at Vietnam sign Family Botanical Name Common Name Chenopodiaceae Halosarcia halecnomoides Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia quinqueflora Beaded samphire Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia blackiana Samphire Poaceae Sporobolis virginicus Cyperaceae Gahnia Trifida Coast sword sedge -

Journal of the International Palm Society Vol. 58(1) Mar. 2014 the INTERNATIONAL PALM SOCIETY, INC

Palms Journal of the International Palm Society Vol. 58(1) Mar. 2014 THE INTERNATIONAL PALM SOCIETY, INC. The International Palm Society Palms (formerly PRINCIPES) Journal of The International Palm Society Founder: Dent Smith The International Palm Society is a nonprofit corporation An illustrated, peer-reviewed quarterly devoted to engaged in the study of palms. The society is inter- information about palms and published in March, national in scope with worldwide membership, and the June, September and December by The International formation of regional or local chapters affiliated with the Palm Society Inc., 9300 Sandstone St., Austin, TX international society is encouraged. Please address all 78737-1135 USA. inquiries regarding membership or information about Editors: John Dransfield, Herbarium, Royal Botanic the society to The International Palm Society Inc., 9300 Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3AE, United Sandstone St., Austin, TX 78737-1135 USA, or by e-mail Kingdom, e-mail [email protected], tel. 44-20- to [email protected], fax 512-607-6468. 8332-5225, Fax 44-20-8332-5278. OFFICERS: Scott Zona, Dept. of Biological Sciences (OE 167), Florida International University, 11200 SW 8 Street, President: Leland Lai, 21480 Colina Drive, Topanga, Miami, Florida 33199 USA, e-mail [email protected], tel. California 90290 USA, e-mail [email protected], 1-305-348-1247, Fax 1-305-348-1986. tel. 1-310-383-2607. Associate Editor: Natalie Uhl, 228 Plant Science, Vice-Presidents: Jeff Brusseau, 1030 Heather Drive, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853 USA, e- Vista, California 92084 USA, e-mail mail [email protected], tel. 1-607-257-0885. -

BURIED TREASURE Summer 2019 Rannveig Wallis, Llwyn Ifan, Porthyrhyd, Carmarthen, UK

BURIED TREASURE Summer 2019 Rannveig Wallis, Llwyn Ifan, Porthyrhyd, Carmarthen, UK. SA32 8BP Email: [email protected] I am still trying unsuccessfully to retire from this enterprise. In order to reduce work, I am sowing fewer seeds and concentrating on selling excess stock which has been repotted in the current year. Some are therefore in quite small numbers. I hope that you find something of interest and order early to avoid any disappointments. Please note that my autumn seed list is included below. This means that seed is fresher and you can sow it earlier. Terms of Business: I can accept payment by either: • Cheque made out to "R Wallis" (n.b. Please do not fill in the amount but add the words “not to exceed £xx” ACROSS THE TOP); • PayPal, please include your email address with the order and wait for an invoice after I dispatch your order; • In cash (Sterling, Euro or US dollar are accepted, in this case I advise using registered mail). Please note that I can only accept orders placed before the end of August. Parcels will be dispatched at the beginning of September. If you are going to be away please let me know so that I can coordinate dispatch. I will not cash your cheque until your order is dispatched. If ordering by email, and following up by post, please ensure that you tick the box on the order form to avoid duplication. Acis autumnalis var pulchella A Moroccan version of this excellent early autumn flowerer. It is quite distinct in the fact that the pedicels and bracts are green rather than maroon as in the type variety. -

Winter-Fall Sale 2002 Palm Trees-Web

Mailing Address: 3233 Brant St. San Diego Ca, 92103 Phone: (619) 291 4605 Fax: (619) 574 1595 E mail: [email protected] Fall/Winter 2002 Palm Price List Tree Citrus 25/+ Band$ 1 gal$ 2 gal$ 3/5 gal$ 7 gal$ 15 gal$ 20 gal$ Box$ Species Pot$ Pot$ gal$ Acanthophoenix crinita $ 30 $ 30-40 $ 35-45 $ 55-65 $ 95 $ 125+ Acanthophoenix rubra $ 35 Acanthophoenix sp. $ 25+ $ 35+ $ 55+ Acoelorrhaphe wrightii $ 15 $ 300 Acrocomia aculeata $ 25+ $ 35 $ 35-45 $ 65 $ 65 $ 100- $ 150+ Actinokentia divaricata 135 Actinorhytis calapparia $ 55 $ 125 Aiphanes acanthophylla $ 45-55 inquire $ 125 Aiphanes caryotaefolia $ 25 $ 55-65 $ 45-55 $ 85 $ 125 Aiphanes elegans $ 20 $ 35 Aiphanes erosa $ 45-55 $ 125 Aiphanes lindeniana $ 55 $ 125 Aiphanes vincentsiana $ 55 Allagoptera arenaria $ 25 $ 40 $ 55 $ 135 Allagoptera campestris $ 35 Alloschmidtia glabrata $ 35 $ 45 $ 55 $ 85 $ 150 $ 175 Alsmithia longipes $ 35+ $ 55 Aphandra natalia $ 35 $ 55 Archontophoenix Alexandrae $ 55 $ 85 $ 125 inquire Archontophoenix Beatricae $ 20 $ 35 $ 55 $ 125 Archontophoenix $ 25 $ 45 $ 65 $ 100 $ 150- $ 200+ $ 310- 175 350 cunninghamiana Archontophoenix maxima $ 25 $ 30 inquire Archontophoenix maxima (Wash River) Archontophoenix myolaensis $ 25+ $ 30 $ 50 $ 75 $ 125 Archontophoenix purpurea $ 30 $ 25 $ 35 $ 50 $ 85 $ 125 $ 300+ Archontophoenix sp. Archontophoenix tuckerii (peach $ 25+ $ 55 river) Areca alicae $ 45 Areca catechu $ 20 $ 35 $ 45 $ 125 Areca guppyana $ 30 $ 45 Areca ipot $ 45 Areca triandra $ 25 $ 30 $ 95 $ 125 Areca vestiaria $ 25 $ 30-35 $ 35-40 $ 55 $ 85-95 $ 125 Arecastrum romanzoffianum $ 125 Arenga australasica $ 20 $ 30 $ 35 $ 45-55 $ 85 $ 125 Arenga caudata $ 20 $ 30 $ 45 $ 55 $ 75 $ 100 Arenga engleri $ 20 $ 60 $ 35 $ 45 $ 85 $ 125 $ 200 $ 300+ Arenga hastata $ 25 www.junglemusic.net Page 1 of 22 Tree Citrus 25/+ Band$ 1 gal$ 2 gal$ 3/5 gal$ 7 gal$ 15 gal$ 20 gal$ Box$ Species Pot$ Pot$ gal$ Arenga hookeriana inquire Arenga micranthe 'Lhutan' $ 20 inquire Arenga pinnata $ 35 $ 50 $ 85 $ 125 Arenga sp. -

From Genes to Genomes: Botanic Gardens Embracing New Tools for Conservation and Research Volume 18 • Number 1

Journal of Botanic Gardens Conservation International Volume 18 • Number 1 • February 2021 From genes to genomes: botanic gardens embracing new tools for conservation and research Volume 18 • Number 1 IN THIS ISSUE... EDITORS Suzanne Sharrock EDITORIAL: Director of Global Programmes FROM GENES TO GENOMES: BOTANIC GARDENS EMBRACING NEW TOOLS FOR CONSERVATION AND RESEARCH .... 03 Morgan Gostel Research Botanist, FEATURES Fort Worth Botanic Garden Botanical Research Institute of Texas and Director, GGI-Gardens NEWS FROM BGCI .... 06 Jean Linksy FEATURED GARDEN: THE NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Magnolia Consortium Coordinator, ECOLOGICAL PARK & BOTANIC GARDENS .... 09 Atlanta Botanical Garden PLANT HUNTING TALES: GARDENS AND THEIR LESSONS: THE JOURNAL OF A BOTANY STUDENT Farahnoz Khojayori .... 13 Cover Photo: Young and aspiring scientists assist career scientists in sampling plants at the U.S. Botanic Garden for TALKING PLANTS: JONATHAN CODDINGTON, the Global Genome Initiative (U.S. Botanic Garden). DIRECTOR OF THE GLOBAL GENOME INITIATIVE .... 16 Design: Seascape www.seascapedesign.co.uk BGjournal is published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI). It is published twice a year. Membership is open to all interested individuals, institutions and organisations that support the aims of BGCI. Further details available from: ARTICLES • Botanic Gardens Conservation International, Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3BW UK. Tel: +44 (0)20 8332 5953, Fax: +44 (0)20 8332 5956, E-mail: [email protected], www.bgci.org BANKING BOTANICAL BIODIVERSITY WITH THE GLOBAL GENOME • BGCI (US) Inc, The Huntington Library, BIODIVERSITY NETWORK (GGBN) Art Collections and Botanical Gardens, Ole Seberg, Gabi Dröge, Jonathan Coddington and Katharine Barker .... 19 1151 Oxford Rd, San Marino, CA 91108, USA. -

Saving Tahina — You Can Help

July 2020 NEWSLETTER SAVING TAHINA — YOU CAN HELP PalmTalk (the public forum of the International Palm Society) is initiating a pro- gram to preserve Tahina spectabilis, an endangered palm that PalmTalk brought to the world’s attention in 2007. The discovery of this enormous, new palm gen- erated worldwide interest, but now due to its extremely limited and fragile range in Madagascar, Tahina needs our help. Please visit PalmTalk (go to www. palms.org, and click on the PalmTalk Forums tab) to see how the IPS and the Roy- al Botanic Gardens, Kew are partnering with a local village in Madagascar to help save this amazing palm. You can make a donation to the pro- ject and be a part of this unique partnership in conser- vation. Please donate today! One of the first photos posted on PalmTalk of the mysterious palm that came to be known as Tahina spectabilis and the little girl (at the time) for whom it was named, Anne-Tahina Metz. Volume 8.06 · July 2020 · Newsletter of the International Palm Society | Editor: Andy Hurwitz [email protected] Virtual hiking on Reunion Island, lowlands editionby Andy Hurwitz This article continues the “virtual hike” and tour of Reunion’s palms that began in last month’s News- letter. This month, we explore the palms and landscapes of the low to middle elevations. We begin by traveling to the windward eastern coast of the island, just south of Piton-Sainte-Rose, to ramble in Anse des Cascades. This idyllic cove is situated among groves of palm trees. The park is cool and shady. -

Current Plant Availability List, Including Descriptions 2021 Issue No 6: Final Autumn Stock Pelham Plants Nursery Ltd

Current plant availability list, including descriptions 2021 Issue no 6: Final autumn stock Pelham Plants Nursery Ltd Listed below are the plants currently available. Please use this list to order from us by email at [email protected] or over the phone on 07377 145970. Please use the most recent version of this list as more varieties are being added all the time. Some cultivars produced in small numbers may also sell out. We are proud of ‘home growing’ all our plants. The list will grow and change substantially as many new varieties become available week by week. It is also advisable to book to visit the nursery in person for the best range and advice. It can be difficult to keep this list up to date at our busiest times or when batches are small. We reserve the right to withdraw plants or changes prices without notice. Full explanation, delivery charges and terms and conditions are listed on our website www.pelhamplants.co.uk Plants currently Approx Price Description available pot size Acis autumnalis. AGM. 0.5L £4.50 A little 'Leucojum' now renamed Acis. Little white bonnets in autumn over grassy foliage and stems. Ideal for a focal pot. 10cm. Aconitum 'Blue Opal'. 2.0L £8.50 Opalescent violet-blue flowers in late summer. Aconitum carmichaelii 2.0L £8.50 syn. Late Vintage. Originally a seed strain, this is a valuable late 'Spätlese'. summer flowering selection with lilac-purple flowers from pale green buds. Aconitum carmichaelii 2.0L £8.50 Late summer flowering in a particularly good cobalt blue. -

2951 – 3000 Trinidad to British Guiana

2951 – 3000 Trinidad to British Guiana [Inside cover] Book 9 Acanthophoenix 2956 Lecythis 2963 Acrocomia 2961 Licuala 2978 Ananas 2993 Livistona 2982 Archontophoenix 2983 Lodoicea 2985 Areca 2953 2953 Mauritia 2984 “ 2954 Mokka-mokka 2997 Astrocaryum 2957 Nipa 2981 “ 2986 Pachira 2976 “ 2987 “ 3000 Asystasia 2964 Passiflora 2952 Bauhinia 2960 “ 2995 Borassus 2979 Peltogyne 2970 Bromelia 2996 Pithecolobium 2965 Caryocar 2999 Randia 2994 Citrus 2998 Samanea 2966 Copernicia 2977 Undetermined 2967 Crotolaria 2973 “ In ink:]Ochna 2971 “ 2974 “ 2972 Desmoncus 2951 “ 2989 Diospyrus 2968 “ 2990 Euterpe 2955 “ 2991 Gmelina 2969 “ 2992 Hyphaene 2980 Zingerberaciae 2958 Ixora 2975 TILLANDSIA 2996 Jacaranda 2962 2951 Demoncus minor? See Harold Loomis’ notes and photo of inflorescence. #54 Villainously spacing & hooked climbing palm reminding one of those terrible Rattan palms of the Orient. When in fruit its bunches of deep scarlet fruits are attractive. A denizen of the deep shade forest and requiring moisture. From my experience in Coconut Grove with this genus I judge it wants half shade. Collected in Arena Forest Reserve Trinidad. 2/4/32 [In pencil] Loomis Photo 220 See D. F. Photo 18454-5 2952 P. H. Dorsett [In ink] “rubra?” Passiflora Sp Wild species of passion vine collected in the outskirts of the town of Eleuthera Bluff Island of Eleuthera Bahamas. Attractive looking species useful [Break in text, in ink] 1 single plant in pot Dec. 14/32. C. F. [Continuation of text] for breeding purposes. 1-7-32 (I’d like a few seeds or plants for my passiflora collection in Coconut Grove) Passiflora sp. Wild species growing in pothole in rocky soil of Eleuthera Bluff a colored town on Eleuthera Island. -

Supporting Information Appendix Pliocene Reversal of Late Neogene

1 Supporting Information Appendix 2 Pliocene reversal of late Neogene aridification 3 4 J.M.K. Sniderman, J. Woodhead, J. Hellstrom, G.J. Jordan, R.N. Drysdale, J.J. Tyler, N. 5 Porch 6 7 8 SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS AND METHODS 9 10 Pollen analysis. We attempted to extract fossil pollen from 81 speleothems collected from 11 16 caves from the Western Australian portion of the Nullarbor Plain. Nullarbor speleothems 12 and caves are essentially “fossil” features that appear to have been preserved by very slow 13 rates of landscape change in a semi-arid landscape. Sample collection targeted fallen, well 14 preserved speleothems in multiple caves. U-Pb dates of these speleothems (Table S3) 15 ranged from late Miocene (8.19 Ma) to Middle Pleistocene (0.41 Ma), with an average age 16 of 4.11 Ma. 17 Fossil pollen typically is present in speleothems in very low concentrations, so pollen 18 processing techniques were developed to minimize contamination by modern pollen (1), but 19 also to maximize recovery, to accommodate the highly variable organic matter content of the 20 speleothems, and to remove a clay- to fine silt-sized mineral fraction present in many 21 samples, which was resistant to cold HF and which can become electrostatically attracted to 22 pollen grains, inhibiting their identification. Stalagmite and flowstone samples of 30-200 g 23 mass were first cut on a diamond rock saw in order to remove any obviously porous material. 24 All subsequent physical and chemical processes were carried out within a HEPA-filtered 25 exhausting clean air cabinet in an ISO Class 7 clean room. -

RCM028 Hutt Lagoon Condition Report

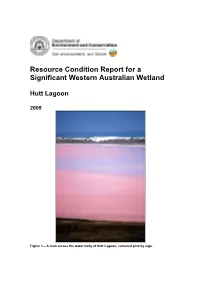

Resource Condition Report for a Significant Western Australian Wetland Hutt Lagoon 2009 Figure 1 – A view across the water body at Hutt Lagoon, coloured pink by alga. This report was prepared by: Anna Nowicki, Technical Officer, Department of Environment and Conservation, PO Box 51, Wanneroo 6946 Adrian Pinder, Senior Research Scientist, Department of Environment and Conservation, PO Box 51, Wanneroo 6946 Stephen Kern, Botanist, Department of Environment and Conservation, Locked Bag 104 Bentley Delivery Centre 6983 Glen Daniel, Environmental Officer, Department of Environment and Conservation, Locked Bag 104 Bentley Delivery Centre 6983 Invertebrate sorting and identification by: Nadine Guthrie, Research Scientist, Department of Environment and Conservation, PO Box 51, Wanneroo 6946 Ross Gordon, Project Officer, Department of Environment and Conservation, PO Box 51, Wanneroo 6946 Prepared for: Inland Aquatic Integrity Resource Condition Monitoring Project, Strategic Reserve Fund, Department of Environment and Conservation August 2009 Suggested Citation: Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC) (2009). Resource Condition Report for a Significant Western Australian Wetland: Hutt Lagoon. Department of Environment and Conservation, Perth, Western Australia. Contents 1. Introduction.........................................................................................................................1 1.1. Site Code ...............................................................................................................1 1.2. -

Red Palm Mite)

Crop Protection Compendium Datasheet report for Raoiella indica (red palm mite) Top of page Pictures Picture Title Caption Copyright Adult The red palm mite (Raoiella indica), an invasive species in the Caribbean, may threaten USDA- mite several important palms found in the southern USA. (Original magnified approx. 300x.) ARS Photo by Eric Erbe; Digital colourization by Chris Pooley. Colony Colony of red palm mites (Raoiella indica) on coconut leaflet, from India. Bryony of Taylor mites Colony Close-up of a colony of red palm mites (Raoiella indica) on coconut leaflet, from India. Bryony of Taylor mites Top of page Identity Preferred Scientific Name Raoiella indica Hirst (1924) Preferred Common Name red palm mite International Common Names English: coconut red mite; frond crimson mite; leaflet false spider mite; red date palm mite; scarlet mite EPPO code RAOIIN (Raoiella indica) Top of page Taxonomic Tree Domain: Eukaryota Kingdom: Metazoa Phylum: Arthropoda Subphylum: Chelicerata Class: Arachnida Subclass: Acari Superorder: Acariformes Suborder: Prostigmata Family: Tenuipalpidae Genus: Raoiella Species: Raoiella indica / Top of page Notes on Taxonomy and Nomenclature R. indica was first described in the district of Coimbatore (India) by Hirst in 1924 on coconut leaflets [Cocos nucifera]. A comprehensive taxonomic review of the genus and species was carried out by Mesa et al. (2009), which lists all suspected junior synonyms of R. indica, including Raoiella camur (Chaudhri and Akbar), Raoiella empedos (Chaudhri and Akbar), Raoiella obelias (Hasan and Akbar), Raoiella pandanae (Mohanasundaram), Raoiella phoenica (Meyer) and Raoiella rahii (Akbar and Chaudhri). The review also highlighted synonymy with Rarosiella cocosae found on coconut in the Philippines.