NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification and Characterization of the Forkhead Box

IDENTIFICATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF THE FORKHEAD BOX FAMILY OF TRANSCRIPTIONAL REGULATORS IN PARASITIC SCHISTOSOMES by MELISSA M. VARRECCHIA Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of philosophy Department of Biology CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August 2017 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of Melissa M. Varrecchia candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Committee Chair Michael F. Benard Committee Member Emmitt R. Jolly Committee Member Christopher A. Cullis Committee Member Claudia M. Mizutani Committee Member Brian M. McDermott Date of Defense June 6, 2017 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. ii Dedication I would like to dedicate this dissertation to my Mom and Dad. Mom, thank you for your endless love, support and encouragement throughout the years. Dad, I miss you and I know that you are with me always, cheering me on in spirit. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………...1 List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………..6 List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………....8 Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………..…11 List of Abbreviations…………………………………………………………………...13 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………15 Chapter 1: Introduction………………………………………………………………..17 1.1 Schistosomiasis………………………………………………………………17 1.2 Pathogenesis and treatment…………………………………………………..18 1.3 Schistosome life cycle………………………………………………………..20 1.4 Schistosome morphology -

The Forkhead-Box Family of Transcription Factors: Key Molecular Players in Colorectal Cancer Pathogenesis Paul Laissue

Laissue Molecular Cancer (2019) 18:5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-019-0938-x REVIEW Open Access The forkhead-box family of transcription factors: key molecular players in colorectal cancer pathogenesis Paul Laissue Abstract Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly occurring cancer worldwide and the fourth most frequent cause of death having an oncological origin. It has been found that transcription factors (TF) dysregulation, leading to the significant expression modifications of genes, is a widely distributed phenomenon regarding human malignant neoplasias. These changes are key determinants regarding tumour’s behaviour as they contribute to cell differentiation/proliferation, migration and metastasis, as well as resistance to chemotherapeutic agents. The forkhead box (FOX) transcription factor family consists of an evolutionarily conserved group of transcriptional regulators engaged in numerous functions during development and adult life. Their dysfunction has been associated with human diseases. Several FOX gene subgroup transcriptional disturbances, affecting numerous complex molecular cascades, have been linked to a wide range of cancer types highlighting their potential usefulness as molecular biomarkers. At least 14 FOX subgroups have been related to CRC pathogenesis, thereby underlining their role for diagnosis, prognosis and treatment purposes. This manuscript aims to provide, for the first time, a comprehensive review of FOX genes’ roles during CRC pathogenesis. The molecular and functional characteristics of most relevant FOX molecules (FOXO, FOXM1, FOXP3) have been described within the context of CRC biology, including their usefulness regarding diagnosis and prognosis. Potential CRC therapeutics (including genome-editing approaches) involving FOX regulation have also been included. Taken together, the information provided here should enable a better understanding of FOX genes’ function in CRC pathogenesis for basic science researchers and clinicians. -

Molecular Cloning and Characterization of a Human PAX-7 Cdna Expressed in Normal and Neoplastic Myocytes

4574-4582 Nucleic Acids Research, 1994, Vol. 22, No. 22 .:/ 1994 Oxford University Press Molecular cloning and characterization of a human PAX-7 cDNA expressed in normal and neoplastic myocytes Beat W.Schafer*, Thomas Czerny1, Michele Bernasconi, Michele Genini and Meinrad Busslinger1 University of Zurich, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Clinical Chemistry, Steinwiesstrasse 75, 8032 Zurich, Switzerland and 'Research Institute of Molecular Pathology, Dr. Bohr-Gasse 7, 1030 Vienna, Austria Received August 25, 1994; Revised and Accepted October 11, 1994 EMBL accession no. Z35141 ABSTRACT The myogenic basic helix-loop-helix proteins are MRF4 (myf6) of the myogenic basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) essential components of the regulatory network con- protein family (for review, see ref. 1,2). Recent gene targeting trolling vertebrate myogenesis. However, determined experiments in mice demonstrated that mice lacking either both myoblasts appear in the limb buds which do not initially myoD and myf5, or myogenin alone display severe skeletal express any member of this transcription factor family. muscle deficiencies (3-5) which underscores the importance of In a search for potential novel regulators of myogene- this family of transcription factors for myogenesis. In addition, sis, a human PAX-7 cDNA was isolated from primary these experiments placed myoD and myf5 upstream of myogenin myoblasts. Analysis of the DNA-binding properties of in a possible transcriptional hierarchy (6). The myogenic bHLH the Pax-7 paired domain revealed that it binds DNA in factors have furthermore the potential to convert several non- a sequence-specific manner indistinguishable from that muscle cell types to the muscle phenotype upon ectopic expression of the paralogous Pax-3 protein. -

Tissue-Specific Metabolic Regulation of FOXO-Binding Protein

cells Review Tissue-Specific Metabolic Regulation of FOXO-Binding Protein: FOXO Does Not Act Alone Noriko Kodani 1 and Jun Nakae 2,* 1 Division of Nephrology, Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo 160-8582, Japan; [email protected] 2 Department of Physiology, International University of Health and Welfare School of Medicine, Narita 286-8686, Japan * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-476-20-7701 Received: 17 January 2020; Accepted: 10 March 2020; Published: 13 March 2020 Abstract: The transcription factor forkhead box (FOXO) controls important biological responses, including proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, metabolism, and oxidative stress resistance. The transcriptional activity of FOXO is tightly regulated in a variety of cellular processes. FOXO can convert the external stimuli of insulin, growth factors, nutrients, cytokines, and oxidative stress into cell-specific biological responses by regulating the transcriptional activity of target genes. However, how a single transcription factor regulates a large set of target genes in various tissues in response to a variety of external stimuli remains to be clarified. Evidence indicates that FOXO-binding proteins synergistically function to achieve tightly controlled processes. Here, we review the elaborate mechanism of FOXO-binding proteins, focusing on adipogenesis, glucose homeostasis, and other metabolic regulations in order to deepen our understanding and to identify a novel therapeutic target for the prevention and treatment of metabolic disorders. Keywords: FOXO; transcription factor; FOXO-binding protein 1. Introduction Forkhead box (FOXO) transcription factors play important roles in apoptosis, the cell cycle, DNA damage repair, oxidative stress, cell differentiation, glucose metabolism, and other cellular functions [1]. -

Systematic Functional Profiling of Transcription Factor

ARTICLE Received 3 Dec 2014 | Accepted 24 Feb 2015 | Published 7 Apr 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7757 OPEN Systematic functional profiling of transcription factor networks in Cryptococcus neoformans Kwang-Woo Jung1,*, Dong-Hoon Yang1,*, Shinae Maeng1, Kyung-Tae Lee1, Yee-Seul So1, Joohyeon Hong2, Jaeyoung Choi3, Hyo-Jeong Byun1, Hyelim Kim1, Soohyun Bang1, Min-Hee Song1, Jang-Won Lee1, Min Su Kim1, Seo-Young Kim1, Je-Hyun Ji1, Goun Park1, Hyojeong Kwon1, Suyeon Cha1, Gena Lee Meyers1,LiLiWang1, Jooyoung Jang1, Guilhem Janbon4, Gloria Adedoyin5, Taeyup Kim5, Anna K. Averette5, Joseph Heitman5, Eunji Cheong2, Yong-Hwan Lee3, Yin-Won Lee3 & Yong-Sun Bahn1 Cryptococcus neoformans causes life-threatening meningoencephalitis in humans, but its overall biological and pathogenic regulatory circuits remain elusive, particularly due to the presence of an evolutionarily divergent set of transcription factors (TFs). Here, we report the construction of a high-quality library of 322 signature-tagged gene-deletion strains for 155 putative TF genes previously predicted using the DNA-binding domain TF database, and examine their in vitro and in vivo phenotypic traits under 32 distinct growth conditions. At least one phenotypic trait is exhibited by 145 out of 155 TF mutants (93%) and B85% of them (132/155) are functionally characterized for the first time in this study. The genotypic and phenotypic data for each TF are available in the C. neoformans TF phenome database (http://tf.cryptococcus.org). In conclusion, our phenome-based functional analysis of the C. neoformans TF mutant library provides key insights into transcriptional networks of basidiomycetous fungi and human fungal pathogens. 1 Department of Biotechnology, Center for Fungal Pathogenesis, College of Life Science and Biotechnology, Yonsei University, Seoul 120-749, Korea. -

CRD1 Domain CRD1 Domain

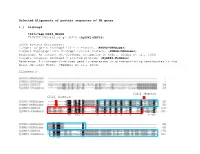

Selected Alignments of protein sequences of NR genes 1.) Dickkopf t22117aep|DKK3_MOUSE TRINITY_DN37863_c0_g1 ORF10 (HyDKK3|ORF10) HyDKK protein References: 1.Hydra Vulgaris Dickkopf 1/2/4-A Protein, (HYDVU-DKKGuder) 2.Hydra Magnipapillata Dickkopf 1/2/4-A Protein, (HYMAG-DKKGuder) Reference: An ancient Wnt-Dickkopf antagonism in Hydra. (Guder et al., 2006) 3.Hydra vulgaris Dickkopf-3 related protein, (HyDKK3-Fedders) Reference: A Dickkopf-3-related gene is expressed in differentiating nematocytes in the basal metazoan Hydra. (Fedders et al., 2004) Alignments: CRD1 domain CRD1 domain Vertebrate Dickkopf molecules consist of two cysteine-rich domains (CRD1 and CRD2), which are separated by a spacer region, diagnostic for grouping of Dkk proteins. CRD2 is necessary and sufficient to repress canonical Wnt signaling by competing with the Wnt-Frizzled complex for binding to the Lrp5/Lrp6 receptor. CRD1 is thought to have a modulating function on CRD2. HyDKK1-Guder protein only has the CRD2 domain (blue boxes). HyDKK3|ORF10 and HyDKK-Fedders have CRD2 (blue box) and CRD1 domains (red box). _________________________________________________________________________________________ 2.) Spinalin t38568aep TRINITY_DN2600_c0_g1ORF15 (Spin|ORF15) AAC39121.1 spinalin [Hydra vulgaris](Koch et al., 1998) ACM79874.1 nematoblast-specific protein nb054-sv9, partial [Hydra vulgaris] (Milde et al., 2009) XP_012553808.1 PREDICTED: midasin [Hydra vulgaris] Alignment of AAC39121.1, ACM79874.1, t38568aep, XP_012553808.1 and Spin|ORF15: XP_012553808.1 is the most complete sequence. AAC39121.1 and ACM79874.1 are both part of this sequence-indicating that the spinalin sequence published by Koch et al 1998 (Koch et al., 1998)only covers the 254 aminao acids of a 695 amino acids long protein. -

Forkhead Transcription Factors: Key Players in Development and Metabolism

Developmental Biology 250, 1–23 (2002) doi:10.1006/dbio.2002.0780 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE REVIEW provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Forkhead Transcription Factors: Key Players in Development and Metabolism Peter Carlsson*,1 and Margit Mahlapuu† *Department of Molecular Biology, Go¨teborg University, Box 462, SE-405 30 Go¨teborg, Sweden; and †Arexis AB, Kroksla¨tts Fabriker 30, 431 37 Mo¨lndal, Sweden INTRODUCTION fungi and a wide variety of metazoans. Their absence in the Arabidopsis genome and failure to identify forkhead genes Transcription factors are modular proteins where distinct in any protist, support the view that this gene family is functions, such as DNA binding, trans-activation or trans- found exclusively in animals and fungi. Thus, the distribu- repression, are often contained within separable domains. tion of forkhead genes lends further support to opisthokonts DNA-binding domains tend to be particularly well con- as a well-defined evolutionary supergroup (Baldauf, 1999). served and can be used as the basis for a classification that Mycetozoa (Myxozoa) have been classified as fungi or reflects phylogenetic relationships. Transcription factors protists and more recently as metazoans (Siddall et al., with the same basic design in their interaction with DNA 1995; Smothers et al., 1994). However, the apparent lack of also tend to be related in function and to share properties forkhead genes in Dictyostelium supports the recent reclas- such as the ability to heterodimerize or to convey certain sification of Mycetozoa as a separate clade close to, but intracellular signals. distinct from, opisthokonts (Baldauf et al., 2000). -

Foxk1 Promotes Cell Proliferation and Represses Myogenic Differentiation

Research Article 5329 Foxk1 promotes cell proliferation and represses myogenic differentiation by regulating Foxo4 and Mef2 Xiaozhong Shi1, Alicia M. Wallis1, Robert D. Gerard2, Kevin A. Voelker3, Robert W. Grange3, Ronald A. DePinho4, Mary G. Garry1 and Daniel J. Garry1,* 1Lillehei Heart Institute, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA 2Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas 75390, USA 3Department of Human Nutrition, Foods and Exercise, Virginia, USA Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, Virginia 24061, USA 4Belfer Institute for Applied Cancer Science, Departments of Medical Oncology, Medicine and Genetics, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA *Author for correspondence ([email protected]) Accepted 9 August 2012 Journal of Cell Science 125, 5329–5337 ß 2012. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd doi: 10.1242/jcs.105239 Summary In response to severe injury, adult skeletal muscle exhibits a remarkable regenerative capacity due to a resident muscle stem/progenitor cell population. While a number of factors are expressed in the muscle progenitor cell (MPC) population, the molecular networks that govern this cell population remain an area of active investigation. In this study, utilizing knockdown techniques and overexpression of Foxk1 in the myogenic lineage, we observed dysregulation of Foxo and Mef2 downstream targets. Utilizing an array of technologies, we establish that Foxk1 represses the transcriptional activity of Foxo4 and Mef2 and physically interacts with Foxo4 and Mef2, thus promoting MPC proliferation and antagonizing the myogenic lineage differentiation program, respectively. Correspondingly, knockdown of Foxk1 in C2C12 myoblasts results in cell cycle arrest, and Foxk1 overexpression in C2C12CAR myoblasts retards muscle differentiation. -

A Novel Class of Winged Helix-Turn-Helix Protein: the DNA-Binding Domain of Mu Transposase

A novel class of winged helix-turn-helix protein: the DNA-binding domain of Mu transposase Robert T Clubb1 , James G Omichinski1 , Harri Savilahti2 , Kiyoshi Mizuuchi 2, Angela M Gronenborn1 * and G Marius Clore1* 1Laboratory of Chemical Physics and 2 Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Building 5, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892-0520, USA Background: Mu transposase (MuA) is a multidomain seven-residue turn connecting them comprise a helix- protein encoded by the bacteriophage Mu genome. It turn-helix (HTH) motif. In addition, there is a long is responsible for translocation of the Mu genome, nine-residue flexible loop or wing connecting strands B2 76 which is the largest and most efficient transposon and B3 of the sheet. NMR studies of MuA complexed known. While the various domains of MuA have been with a consensus DNA site from the internal activation delineated by means of biochemical methods, no data region of the Mu genome indicate that the wing and have been obtained to date relating to its tertiary the second helix of the HTH motif are significantly structure. perturbed upon DNA binding. Results: We have solved the three-dimensional solution Conclusions: While the general appearance of the 76 structure of the DNA-binding domain (residues 1-76; DNA-binding domain of MuA is similar to that of MuA7 6) of MuA by multidimensional heteronuclear other winged HTH proteins, the connectivity of the NMR spectroscopy. The structure consists of a three- secondary structure elements is permuted. Hence, the membered -helical bundle buttressed by a three- fold of MuA 76 represents a novel class of winged HTH stranded antiparallel P-sheet. -

The Foxo Code

Oncogene (2008) 27, 2276–2288 & 2008 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9232/08 $30.00 www.nature.com/onc REVIEW The FoxO code DR Calnan1,2 and A Brunet1,2,3 1Department of Genetics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA; 2Cancer Biology Program, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA and 3Neurosciences Program, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA The FoxO family of Forkhead transcription factors plays development of a number of tissues (Nakae et al., 2002; an important role in longevity and tumor suppression by Bluher et al., 2003; Holzenberger et al., 2003; Furuyama upregulating target genes involved in stress resistance, et al., 2004; Hosaka et al., 2004; Hu et al., 2004; Paik metabolism, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis.FoxO et al., 2007) (Figure 1). transcription factors translate a variety of environmental FoxO proteins mainly act as potent transcriptional stimuli, including insulin, growth factors, nutrients and activators by binding to the conserved consensus core oxidative stress, into specific gene-expression programs. recognition motif TTGTTTAC (Furuyama et al., 2000; These environmental stimuli control FoxO activity Xuan and Zhang, 2005). FoxO transcription factors primarily by regulating their subcellular localization, promote cell cycle arrest, repair of damaged DNA, but also by affecting their protein levels, DNA-binding detoxification of reactive oxygen species, apoptosis and properties and transcriptional activity.The precise autophagy by upregulating specific gene-expression regulation of FoxO transcription factors is enacted by programs (Figure 1) (Brunet et al., 1999; Dijkers et al., an intricate combination of post-translational modifica- 2000; Medema et al., 2000; Kops et al., 2002; Nemoto tions (PTMs), including phosphorylation, acetylation and and Finkel, 2002; Tran et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2003; ubiquitination, and binding protein partners.An intriguing Murphy et al., 2003; Mammucari et al., 2007; Zhao possibility is that FoxO PTMs may act as a ‘molecular et al., 2007). -

Adjacent to the Recognition Helix

MOLECULAR AND CELLULAR BIOLOGY, Apr. 1994, p. 2755-2766 Vol. 14, No. 4 0270-7306/94/$04.00+0 Copyright ©) 1994, American Society for Microbiology The DNA-Binding Specificity of the Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 3/forkhead Domain Is Influenced by Amino Acid Residues Adjacent to the Recognition Helix DAVID G. OVERDIER, ANNA PORCELLA, AND ROBERT H. COSTA* Department of Biochemistry, College of Medicine, The University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60612-7334 Received 19 November 1993/Returned for modification 4 January 1994/Accepted 19 January 1994 Three distinct hepatocyte nuclear factor 3 (HNF-3) proteins (HNF-3ox, -3Ip, and -3-y) are known to regulate the transcription of liver-specific genes. The HNF-3 proteins bind to DNA as a monomer through a modified helix-turn-helix, known as the winged helix motif, which is also utilized by a number of developmental regulators, including the Drosophila homeotic forkhead (fkh) protein. We have previously described the isolation, from rodent tissue, of an extensive family of tissue-specific HNF-3/fkh homolog (HFH) genes sharing homology in their winged helix motifs. In this report, we have determined the preferred DNA-binding consensus sequence for the HNF-3P protein as well as for two divergent family members, HFH-1 and HFH-2. We show that these HNF-3/fkh proteins bind to distinct DNA sites and that the specificity of protein recognition is dependent on subtle nucleotide alterations in the site. The HNF-3, HFH-1, and HFH-2 consensus binding sequences were also used to search DNA regulatory regions to identify potential target genes. -

Gene Fusions Involving PAX and FOX Family Members in Alveolar Rhabdomyosarcoma

Oncogene (2001) 20, 5736 ± 5746 ã 2001 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950 ± 9232/01 $15.00 www.nature.com/onc Gene fusions involving PAX and FOX family members in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma Frederic G Barr*,1 1Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, 36th Street and Hamilton Walk, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, PA 19104-6082, USA The chromosomal translocations t(2;13)(q35;q14) and Clinical, pathologic and cytogenetic features of alveolar t(1;13)(p36;q14) are characteristic of alveolar rhabdo- rhabdomyosarcoma myosarcoma, a pediatric soft tissue cancer related to the striated muscle lineage. These translocations rearrange Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (ARMS) is one subtype PAX3 and PAX7, members of the paired box transcrip- of rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), a family of pediatric tion factor family, and juxtapose these genes with soft tissue tumors that are related to the skeletal FKHR, a member of the fork head transcription factor muscle lineage (Wexler and Helman, 1997). ARMS was family. This juxtaposition generates PAX3 ± FKHR and initially distinguished from the other major RMS PAX7 ± FKHR chimeric genes that are expressed as subtype, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (ERMS), by chimeric transcripts that encode chimeric proteins. The histologic criteria. As the criteria were re®ned, the fusion proteins, which contain the PAX3/PAX7 DNA subtypes were found to be associated with distinct binding domain and the FKHR transcriptional activation clinical behaviors (Tsokos et al., 1992). ARMS presents domain, activate transcription from PAX-binding sites mainly in adolescents and young adults, often in the with higher potency than the corresponding wild-type vicinity of skeletal muscle in the extremities and trunk, PAX proteins.