Wikileaks 2010: a Glimpse of the Future? by Tim Maurer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romanian Political Science Review Vol. XXI, No. 1 2021

Romanian Political Science Review vol. XXI, no. 1 2021 The end of the Cold War, and the extinction of communism both as an ideology and a practice of government, not only have made possible an unparalleled experiment in building a democratic order in Central and Eastern Europe, but have opened up a most extraordinary intellectual opportunity: to understand, compare and eventually appraise what had previously been neither understandable nor comparable. Studia Politica. Romanian Political Science Review was established in the realization that the problems and concerns of both new and old democracies are beginning to converge. The journal fosters the work of the first generations of Romanian political scientists permeated by a sense of critical engagement with European and American intellectual and political traditions that inspired and explained the modern notions of democracy, pluralism, political liberty, individual freedom, and civil rights. Believing that ideas do matter, the Editors share a common commitment as intellectuals and scholars to try to shed light on the major political problems facing Romania, a country that has recently undergone unprecedented political and social changes. They think of Studia Politica. Romanian Political Science Review as a challenge and a mandate to be involved in scholarly issues of fundamental importance, related not only to the democratization of Romanian polity and politics, to the “great transformation” that is taking place in Central and Eastern Europe, but also to the make-over of the assumptions and prospects of their discipline. They hope to be joined in by those scholars in other countries who feel that the demise of communism calls for a new political science able to reassess the very foundations of democratic ideals and procedures. -

Complete Tape Subject

1 NIXON PRESIDENTIAL MATERIALS STAFF Tape Subject Log (rev. Mar-02) Conversation No. 140-1 Date: August 14, 1972 Time: 7:55 pm Location: Camp David Study Table The Camp David operator talked with the President. Request for a call to John D. Ehrlichman -Ehrlichman’s location Conversation No. 140-2 Date: August 15, 1972 Time: Unknown between 8:43 pm and 9:30 pm Location: Camp David Study Table The President talked with the Camp David operator. [See Conversation No. 202-12] Request for a call to Julie Nixon Eisenhower Conversation No. 140-3 Date: August 15, 1972 Time: 9:30 pm - 9:35 pm Location: Camp David Study Table The President talked with Julie Nixon Eisenhower. [See Conversation No. 202-13] 2 NIXON PRESIDENTIAL MATERIALS STAFF Tape Subject Log (rev. Mar-02) ***************************************************************** BEGIN WITHDRAWN ITEM NO. 1 [Personal returnable] [Duration: 4m 57s ] END WITHDRAWN ITEM NO. 1 ***************************************************************** Conversation No. 140-4 Date: August 16, 1972 Time: Unknown between 8:15 am and 8:21 am Location: Camp David Study Table The President talked with the Camp David operator. [See Conversation No. 202-14] Request for a call to Alexander M. Haig, Jr. Conversation No. 140-5 Date: August 16, 1972 Time: 8:21 am - 8:29 am Location: Camp David Study Table The President talked with Alexander M. Haig, Jr. [See Conversation No. 202-15] Paul C. Warnke -George S. McGovern's statement -Possible briefing of Warnke -Security clearance process -Questions on Pentagon Papers 3 NIXON PRESIDENTIAL MATERIALS STAFF Tape Subject Log (rev. Mar-02) -The President’s instructions -Report by Richard M. -

NAPF Report to UN Secretary General on Disarmament Education

Report to UN Secretary-General on NAPF Disarmament Education Activities The Nuclear Age Peace Foundation (NAPF) has been educating people in the United States and around the world about the urgent need for the abolition of nuclear weapons since 1982. Based in Santa Barbara, California, the Foundation’s mission is to educate and advocate for peace and a world free of nuclear weapons, and to empower peace leaders. The following document was submitted to United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. It will make up a portion of the “Report of the Secretary-General to the 69th Session of the General Assembly on the Implementation of the Recommendations of the 2002 UN Study on Disarmament and Non-Proliferation Education.” Websites www.wagingpeace.org NAPF’s primary website, www.wagingpeace.org, serves as an educational and advocacy tool for members of the public concerned about nuclear weapons issues. During this reporting period, there were over 700,000 unique visitors to this site. The Waging Peace site covers current nuclear weapons policy and other relevant issues of global security. It includes information about the Foundation’s activities and offers visitors the opportunity to participate in online advocacy and activism. The site additionally offers a unique archive section containing hundreds of articles and essays on issues ranging from nuclear weapons policy to international law and youth activism. The site is updated frequently. www.nuclearfiles.org The Foundation’s educational website, www.nuclearfiles.org, details a comprehensive history of the Nuclear Age. It is regularly updated and expanded. By providing background information, an extensive timeline, access to primary documents and analysis, this site is one of the preeminent online educational resources in the field. -

Running Head: Wikileaks and the Censorship of News Media in the U.S

RUNNING HEAD: WIKILEAKS AND THE CENSORSHIP OF NEWS MEDIA IN THE U.S. WikiLeaks and the Censorship of News Media in the U.S. Author: Asa Hilmersson Faculty Mentor: Professor Keeton Ramapo College of New Jersey WIKILEAKS AND THE CENSORSHIP OF NEWS MEDIA IN THE U.S. 1 “Censorship in free societies is infinitely more sophisticated and thorough than in dictatorships, because ‘unpopular ideas can be silenced, and inconvenient facts kept dark, without any need for an official ban’.” – George Orwell Introduction Throughout history, media has been censored or obscured in different ways which seem to fit the dominant ideology or ruling regime. As William Powers (1995) from The Washington Post said; the Nazis were censored, Big Brother was a censor, and nightmare regimes such as China have censors. Though we are all aware of censorship around the world and in history, little do we look to ourselves because as Powers writes, “None of that [censorship] for us. This is America” (para. 3). People in America have long been led to believe that they live in a free world where every voice is heard. It is not until someone uses the opportunities of this right that we see that this freedom of speech might only be an illusion. The emergence of WikiLeaks in 2010 and the censorship exercised against this organization by the United States’ government exemplifies the major obstacles individuals can face when seeking to expose potential wrongdoing by public officials. Through questioning of media’s power as whistleblowers it is hinted that there are institutions which may carry more weight than the truth in making decisions that affect that public interest. -

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections David Hirsh Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK The Working Papers Series is intended to initiate discussion, debate and discourse on a wide variety of issues as it pertains to the analysis of antisemitism, and to further the study of this subject matter. Please feel free to submit papers to the ISGAP working paper series. Contact the ISGAP Coordinator or the Editor of the Working Paper Series, Charles Asher Small. Working Paper Hirsh 2007 ISSN: 1940-610X © Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, Second floor New York, NY 10022 United States Office Telephone: 212-230-1840 www.isgap.org ABSTRACT This paper aims to disentangle the difficult relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. On one side, antisemitism appears as a pressing contemporary problem, intimately connected to an intensification of hostility to Israel. Opposing accounts downplay the fact of antisemitism and tend to treat the charge as an instrumental attempt to de-legitimize criticism of Israel. I address the central relationship both conceptually and through a number of empirical case studies which lie in the disputed territory between criticism and demonization. The paper focuses on current debates in the British public sphere and in particular on the campaign to boycott Israeli academia. Sociologically the paper seeks to develop a cosmopolitan framework to confront the methodological nationalism of both Zionism and anti-Zionism. It does not assume that exaggerated hostility to Israel is caused by underlying antisemitism but it explores the possibility that antisemitism may be an effect even of some antiracist forms of anti- Zionism. -

La Quadrature Du Net Campaigning on Telecoms Package Pan-European Activism for Patching a “Pirated” Law

25th Chaos Communication Congress Nothing to hide Berlin, 2008-12-30 La Quadrature du Net Campaigning on Telecoms Package Pan-european activism for patching a \pirated" law by J´er´emieZimmermann <[email protected]> \Whatever you do will be insignificant, but it is very important that you do it." Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi Contents Prelude 3 Who are we ? 4 Who is La Quadrature du Net ...................................4 Why this name?..........................................4 They support La Quadrature du Net ...............................5 Campaign on Telecoms Package6 Squaring the net..........................................6 The debate is open.........................................7 European Parliament rejects graduated response........................8 Will France Introduce the Digital Guillotine in Europe?....................8 Privacy: Film industry pirates European law..........................9 MEPs want to torpedo the Free Internet on July 7th...................... 10 The \Telecoms Package": out of the shadows, into the light.................. 10 Telecoms Package: vote postponed................................ 11 Telecoms Package: the spectre of the graduated response hangs over Europe......... 12 Telecoms Package: protect the free and just society!...................... 12 Telecoms Package: European democracy's victory already threatened............. 13 Letter sent to all MEPs on september 23rd........................... 14 Graduated Response: The Lesson................................. 15 \Graduated response": Will France -

In Re Motion of Propublica, Inc. for the Release of Court Records [FISC

IN RE OPINIONS & ORDERS OF THIS COURT ADDRESSING BULK COLLECTION OF DATA Docket No. Misc. 13-02 UNDER THE FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE ACT IN RE MOTION FOR THE RELEASE OF Docket No. Misc. 13-08 COURT RECORDS IN RE MOTION OF PROPUBLICA, INC. FOR Docket No. Misc. 13-09 THE RELEASE OF COURT RECORDS BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE THE REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS AND 25 MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS, IN SUPPORT OF THE NOVEMBER 6,2013 MOTION BY THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, ET AL, FOR THE RELEASE OF COURT RECORDS; THE OCTOBER 11, 2013 MOTION BY THE MEDIA FREEDOM AND INFORMATION ACCESS CLINIC FOR RECONSIDERATION OF THIS COURT'S SEPTEMBER 13, 2013 OPINION ON THE ISSUE OF ARTICLE III STANDING; AND THE NOVEMBER 12,2013 MOTION OF PRO PUBLICA, INC. FOR RELEASE OF COURT RECORDS Bruce D. Brown The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press 1101 Wilson Blvd., Suite 1100 Arlington, VA 22209 Counsel for Amici Curiae November 26. 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................... iii IDENTITY OF AMICI CURIAE .................................................................................................... 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ............................................................................................. 2 ARGUMENT ................................................................................................................................. -

Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty's Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism

Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Ash Center Occasional Papers Series Series Editor Tony Saich Deputy Editor Jessica Engelman The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. By training the very best leaders, developing powerful new ideas, and disseminating innovative solutions and institutional reforms, the Center’s goal is to meet the profound challenges facing the world’s citizens. The Ford Foundation is a founding donor of the Center. Additional information about the Ash Center is available at ash.harvard.edu. This research paper is one in a series funded by the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. The views expressed in the Ash Center Occasional Papers Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or of Harvard University. The papers in this series are intended to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. This paper is copyrighted by the author(s). It cannot be reproduced or reused without permission. Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Letter from the Editor The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. -

The Views of the U.S. Left and Right on Whistleblowers Whistleblowers on Right and U.S

The Views of the U.S. Left and Right on Whistleblowers Concerning Government Secrets By Casey McKenzie Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations and European Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Erin Kristin Jenne Word Count: 12,868 CEU eTD Collection Budapest Hungary 2014 Abstract The debates on whistleblowers in the United States produce no simple answers and to make thing more confusing there is no simple political left and right wings. The political wings can be further divided into far-left, moderate-left, moderate-right, far-right. To understand the reactions of these political factions, the correct political spectrum must be applied. By using qualitative content analysis of far-left, moderate-left, moderate-right, far-right news sites I demonstrate the debate over whistleblowers belongs along a establishment vs. anti- establishment spectrum. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgments I would like to express my fullest gratitude to my supervisor, Erin Kristin Jenne, for the all the help see gave me and without whose guidance I would have been completely lost. And to Danielle who always hit me in the back of the head when I wanted to give up. CEU eTD Collection ii Table of Contents Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... i Acknowledgments..................................................................................................................... -

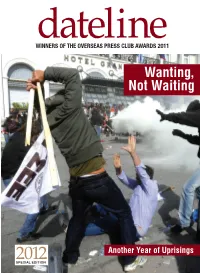

Wanting, Not Waiting

WINNERSdateline OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB AWARDS 2011 Wanting, Not Waiting 2012 Another Year of Uprisings SPECIAL EDITION dateline 2012 1 letter from the president ne year ago, at our last OPC Awards gala, paying tribute to two of our most courageous fallen heroes, I hardly imagined that I would be standing in the same position again with the identical burden. While last year, we faced the sad task of recognizing the lives and careers of two Oincomparable photographers, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, this year our attention turns to two writers — The New York Times’ Anthony Shadid and Marie Colvin of The Sunday Times of London. While our focus then was on the horrors of Gadhafi’s Libya, it is now the Syria of Bashar al- Assad. All four of these giants of our profession gave their lives in the service of an ideal and a mission that we consider so vital to our way of life — a full, complete and objective understanding of a world that is so all too often contemptuous or ignorant of these values. Theirs are the same talents and accomplishments to which we pay tribute in each of our awards tonight — and that the Overseas Press Club represents every day throughout the year. For our mission, like theirs, does not stop as we file from this room. The OPC has moved resolutely into the digital age but our winners and their skills remain grounded in the most fundamental tenets expressed through words and pictures — unwavering objectivity, unceasing curiosity, vivid story- telling, thought-provoking commentary. -

Wikileaks and the Institutional Framework for National Security Disclosures

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL PATRICIA L. BELLIA WikiLeaks and the Institutional Framework for National Security Disclosures ABSTRACT. WikiLeaks' successive disclosures of classified U.S. documents throughout 2010 and 2011 invite comparison to publishers' decisions forty years ago to release portions of the Pentagon Papers, the classified analytic history of U.S. policy in Vietnam. The analogy is a powerful weapon for WikiLeaks' defenders. The Supreme Court's decision in the Pentagon Papers case signaled that the task of weighing whether to publicly disclose leaked national security information would fall to publishers, not the executive or the courts, at least in the absence of an exceedingly grave threat of harm. The lessons of the PentagonPapers case for WikiLeaks, however, are more complicated than they may first appear. The Court's per curiam opinion masks areas of substantial disagreement as well as a number of shared assumptions among the Court's members. Specifically, the Pentagon Papers case reflects an institutional framework for downstream disclosure of leaked national security information, under which publishers within the reach of U.S. law would weigh the potential harms and benefits of disclosure against the backdrop of potential criminal penalties and recognized journalistic norms. The WikiLeaks disclosures show the instability of this framework by revealing new challenges for controlling the downstream disclosure of leaked information and the corresponding likelihood of "unintermediated" disclosure by an insider; the risks of non-media intermediaries attempting to curtail such disclosures, in response to government pressure or otherwise; and the pressing need to prevent and respond to leaks at the source. AUTHOR. -

USA -V- Julian Assange Judgment

JUDICIARY OF ENGLAND AND WALES District Judge (Magistrates’ Court) Vanessa Baraitser In the Westminster Magistrates’ Court Between: THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Requesting State -v- JULIAN PAUL ASSANGE Requested Person INDEX Page A. Introduction 2 a. The Request 2 b. Procedural History (US) 3 c. Procedural History (UK) 4 B. The Conduct 5 a. Second Superseding Indictment 5 b. Alleged Conduct 9 c. The Evidence 15 C. Issues Raised 15 D. The US-UK Treaty 16 E. Initial Stages of the Extradition Hearing 25 a. Section 78(2) 25 b. Section 78(4) 26 I. Section 78(4)(a) 26 II. Section 78(4)(b) 26 i. Section 137(3)(a): The Conduct 27 ii. Section 137(3)(b): Dual Criminality 27 1 The first strand (count 2) 33 The second strand (counts 3-14,1,18) and Article 10 34 The third strand (counts 15-17, 1) and Article 10 43 The right to truth/ Necessity 50 iii. Section 137(3)(c): maximum sentence requirement 53 F. Bars to Extradition 53 a. Section 81 (Extraneous Considerations) 53 I. Section 81(a) 55 II. Section 81(b) 69 b. Section 82 (Passage of Time) 71 G. Human Rights 76 a. Article 6 84 b. Article 7 82 c. Article 10 88 H. Health – Section 91 92 a. Prison Conditions 93 I. Pre-Trial 93 II. Post-Trial 98 b. Psychiatric Evidence 101 I. The defence medical evidence 101 II. The US medical evidence 105 III. Findings on the medical evidence 108 c. The Turner Criteria 111 I.