Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: an Anglican Perspective on State Education

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1995 The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: An Anglican Perspective on State Education George Sochan Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Sochan, George, "The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: An Anglican Perspective on State Education" (1995). Dissertations. 3521. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3521 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1995 George Sochan LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CULTURAL ROLE OF CHRISTIANITY IN ENGLAND, 1918-1931: AN ANGLICAN PERSPECTIVE ON STATE EDUCATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY GEORGE SOCHAN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY, 1995 Copyright by George Sochan Sochan, 1995 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION • ••.••••••••••.•••••••..•••..•••.••.•• 1 II. THE CALL FOR REFORM AND THE ANGLICAN RESPONSE ••.• 8 III. THE FISHER ACT •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 35 IV. NO AGREEMENT: THE FAILURE OF THE AMENDING BILL •. 62 v. THE EDUCATIONAL LULL, 1924-1926 •••••••••••••••• 105 VI. THE HADOW REPORT ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 135 VII. THREE FAILED BILLS, THEN THE DEPRESSION •••••••• 168 VIII. CONCLUSION ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 218 BIBLIOGRAPHY •••••••••.••••••••••.••.•••••••••••••••••.• 228 VITA ...........................................•....... 231 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Since World War II, beginning especially in the 1960s, considerable work has been done on the history of the school system in England. -

Records of Bristol Cathedral

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY’S PUBLICATIONS General Editors: MADGE DRESSER PETER FLEMING ROGER LEECH VOL. 59 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL EDITED BY JOSEPH BETTEY Published by BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 2007 1 ISBN 978 0 901538 29 1 2 © Copyright Joseph Bettey 3 4 No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, 5 electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information 6 storage or retrieval system. 7 8 The Bristol Record Society acknowledges with thanks the continued support of Bristol 9 City Council, the University of the West of England, the University of Bristol, the Bristol 10 Record Office, the Bristol and West Building Society and the Society of Merchant 11 Venturers. 12 13 BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 14 President: The Lord Mayor of Bristol 15 General Editors: Madge Dresser, M.Sc., P.G.Dip RFT, FRHS 16 Peter Fleming, Ph.D. 17 Roger Leech, M.A., Ph.D., FSA, MIFA 18 Secretaries: Madge Dresser and Peter Fleming 19 Treasurer: Mr William Evans 20 21 The Society exists to encourage the preservation, study and publication of documents 22 relating to the history of Bristol, and since its foundation in 1929 has published fifty-nine 23 major volumes of historic documents concerning the city. -

Open PDF 133KB

Select Committee on Communications and Digital Corrected oral evidence: The future of journalism Tuesday 16 June 2020 3 pm Watch the meeting Members present: Lord Gilbert of Panteg (The Chair); Lord Allen of Kensington; Baroness Bull; Baroness Buscombe; Viscount Colville of Culross; Baroness Grender; Lord McInnes of Kilwinning; Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall; Baroness Meyer; Baroness Quin; Lord Storey; The Lord Bishop of Worcester. Evidence Session No. 14 Virtual Proceeding Questions 115 – 122 Witnesses I: Fraser Nelson, Editor, Spectator; and Jason Cowley, Editor, New Statesman. USE OF THE TRANSCRIPT This is a corrected transcript of evidence taken in public and webcast on www.parliamentlive.tv. 1 Examination of witnesses Fraser Nelson and Jason Cowley. Q115 The Chair: I welcome to the House of Lords Select Committee on Communications and Digital and its inquiry into the future of journalism our witnesses for the first session of evidence today, Fraser Nelson and Jason Cowley. Before I ask you to say a little more about yourselves, I should point out that today’s session will be recorded and broadcast live on parliamentlive.tv and a transcript will be produced. Thank you very much for joining us and giving us your time. I know this is Jason’s press day when he will be putting his magazine to bed. I am not sure whether it is the same for Fraser, but we are particularly grateful to you for giving up your time. Our inquiry is into the future of journalism, particularly skills, access to the industry and the impact of technology on the conduct of journalism. -

Bishop of Gloucester, Rachel Treweek

General Synod Safeguarding presentation from Bishop of Gloucester, Rachel Treweek, February 2018 I’m aware that when we talk about safeguarding it engages our hearts, our minds and our guts, and depending on our own experiences, our antennae will be set at different angles. So I hope that in our time of questions there will be opportunity for people to clarify what they’ve heard. I have been asked to say something brief about the Diocese of Gloucester and I look forward to contributing more in response to questions. It was not long after I arrived in Gloucester that Peter Ball, a previous Bishop of Gloucester was finally convicted of horrific abuse - You have the Gibb report (GS Misc. 1172). As I have previously said publicly, I am deeply ashamed of that legacy and deeply sorry; just as I am deeply ashamed and sorry about the abuse people have suffered across the Church which has so often been compounded by wholly inadequate response and a lack of compassion and understanding… .. I do believe that in the present I have the privilege of working with a committed and professional team in Gloucester. And that is not intended to sound defensive. The starting place is the big picture of the good news of the Kingdom of God and the truth that every person is a unique individual with a name, made in the image of God. Transformation, flourishing and reconciliation is at the heart of who God is. Yet we live amid prolific broken relationship including abuse of children and adults, neglect, misused power.. -

Fraser Nelson Editor, the Spectator Media Masters – September 12, 2019 Listen to the Podcast Online, Visit

Fraser Nelson Editor, The Spectator Media Masters – September 12, 2019 Listen to the podcast online, visit www.mediamasters.fm Welcome to Media Masters, a series of one-to-one interviews with people at the top of the media game. Today I’m joined by Fraser Nelson, editor of The Spectator, the world’s oldest weekly magazine. Under his 10-year editorship it has reached a print circulation of over 70,000, the highest in its 190-year history. Previously political editor and associate editor, his roles elsewhere have included political columnist for the News of the World, political editor at the Scotsman, and business reporter with the Times. He is a board director with the Centre for Policy Studies, and the recipient of a number of awards, including the British Society of Magazine Editors’ ‘Editors’ Editor of the Year’. Fraser, thank you for joining me. Great pleasure to be here. Allie, who writes these introductions for me, clearly hates me. Editors’ Editor of the Year from the Editors’ Society. What’s that? Yes, it is, because it used to be ‘Editor of the Year’ back in the old days, and then you got this massive inflation, so now every award they give is now Editor of the Year (something or another). I see. Now that leads to a problem, so what do you call the overall award? Yes, the top one. The grand enchilada. Yes. So it’s actually a great honour. They ask other editors to vote every year. Wow. So this isn’t a panel of judges who decides the number one title, it’s other editors, and they vote for who’s going to be the ‘Editors’ Editor of the Year’, and you walk off with this lovely big trophy. -

Theos Turbulentpriests Reform:Layout 1

Turbulent Priests? The Archbishop of Canterbury in contemporary English politics Daniel Gover Theos Friends’ Programme Theos is a public theology think tank which seeks to influence public opinion about the role of faith and belief in society. We were launched in November 2006 with the support of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, and the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O'Connor. We provide • high-quality research, reports and publications; • an events programme; • news, information and analysis to media companies and other opinion formers. We can only do this with your help! Theos Friends receive complimentary copies of all Theos publications, invitations to selected events and monthly email bulletins. If you would like to become a Friend, please detach or photocopy the form below, and send it with a cheque to Theos for £60. Thank you. Yes, I would like to help change public opinion! I enclose a cheque for £60 made payable to Theos. Name Address Postcode Email Tel Data Protection Theos will use your personal data to inform you of its activities. If you prefer not to receive this information please tick here By completing you are consenting to receiving communications by telephone and email. Theos will not pass on your details to any third party. Please return this form to: Theos | 77 Great Peter Street | London | SW1P 2EZ S: 97711: D: 36701: Turbulent Priests? what Theos is Theos is a public theology think tank which exists to undertake research and provide commentary on social and political arrangements. We aim to impact opinion around issues of faith and belief in The Archbishop of Canterbury society. -

Updating Report for SCCA Campaign

Updating Report for SCCA Campaign 2012 proved incredibly important in raising public awareness of the institutional cultures and dynamics that hinder the effective implementation of Child Protection/Safeguarding policies and procedures. The Savile Inquiries, the Rochdale cases and the inquiries and police investigation into child sexual abuse perpetrated by clergy within the Diocese of Chichester all in 2012 raise considerable concerns about how those placed in positions of authority within institutions, local authorities and police services as well as within the wider communities respond to Child Sexual Abuse that is taking place in some cases quite literally before their eyes. The campaign and the Government’s response The Stop Church Child Abuse (“SCCA”) campaign was launched in March 2012. The campaign is an alliance of clergy sexual abuse survivors, charities supporting survivors, specialist lawyers and interested individuals working in the field of child safeguarding. The campaign aims to highlight the serious safeguarding failures of church institutions. The campaign and many individuals have called on the Government to institute an independent inquiry into child sexual abuse perpetrated by clergy, religious and other church officials within all Dioceses and institutions of the Catholic Church in England & Wales and the Church of England and in Wales. Many contacts and letters have passed between the campaign’s supporters and the MPs. The Government response to this pressure has been (quoting from the Education Secretary’s letter of 25th May 2012):- 1) “No child should ever have to tolerate abuse. I am not however convinced of the need for a public inquiry, as the key issues are already being addressed by reforms we have underway. -

ND Sept 2019.Pdf

usually last Sunday, 5pm. Mass Tuesday, Friday & Saturday, 9.30am. Canon David Burrows SSC , 01422 373184, rectorofel - [email protected] parish directory www.ellandoccasionals.blogspot.co.uk FOLKESTONE Kent , St Peter on the East Cliff A Society BATH Bathwick Parishes , St.Mary’s (bottom of Bathwick Hill), Wednesday 9.30am, Holy Hour, 10am Mass Friday 9.30am, Sat - Parish under the episcopal care of the Bishop of Richborough . St.John's (opposite the fire station) Sunday - 9.00am Sung Mass at urday 9.30am Mass & Rosary. Fr.Richard Norman 0208 295 6411. Sunday: 8am Low Mass, 10.30am Solemn Mass. Evensong 6pm. St.John's, 10.30am at St.Mary's 6.00pm Evening Service - 1st, Parish website: www.stgeorgebickley.co.uk Weekdays - Low Mass: Tues 7pm, Thur 12 noon. 3rd &5th Sunday at St.Mary's and 2nd & 4th at St.John's. Con - http://stpetersfolk.church e-mail :[email protected] tact Fr.Peter Edwards 01225 460052 or www.bathwick - BURGH-LE-MARSH Ss Peter & Paul , (near Skegness) PE24 parishes.org.uk 5DY A resolution parish in the care of the Bishop of Richborough . GRIMSBY St Augustine , Legsby Avenue Lovely Grade II Sunday Services: 9.30am Sung Mass (& Junior Church in term Church by Sir Charles Nicholson. A Forward in Faith Parish under BEXHILL on SEA St Augustine’s , Cooden Drive, TN39 3AZ time) On 5th Sunday a Group Mass takes place in one of the 6 Bishop of Richborough . Sunday: Parish Mass 9.30am, Solemn Saturday: Mass at 6pm (first Mass of Sunday)Sunday: Mass at churches in the Benefice. -

Time for Reflection

All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group TIME FOR REFLECTION A REPORT OF THE ALL-PARTY PARLIAMENTARY HUMANIST GROUP ON RELIGION OR BELIEF IN THE UK PARLIAMENT The All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group acts to bring together non-religious MPs and peers to discuss matters of shared interests. More details of the group can be found at https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm/cmallparty/190508/humanist.htm. This report was written by Cordelia Tucker O’Sullivan with assistance from Richy Thompson and David Pollock, both of Humanists UK. Layout and design by Laura Reid. This is not an official publication of the House of Commons or the House of Lords. It has not been approved by either House or its committees. All-Party Groups are informal groups of Members of both Houses with a common interest in particular issues. The views expressed in this report are those of the Group. © All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group, 2019-20. TIME FOR REFLECTION CONTENTS FOREWORD 4 INTRODUCTION 6 Recommendations 7 THE CHAPLAIN TO THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS 8 BISHOPS IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS 10 Cost of the Lords Spiritual 12 Retired Lords Spiritual 12 Other religious leaders in the Lords 12 Influence of the bishops on the outcome of votes 13 Arguments made for retaining the Lords Spiritual 14 Arguments against retaining the Lords Spiritual 15 House of Lords reform proposals 15 PRAYERS IN PARLIAMENT 18 PARLIAMENT’S ROLE IN GOVERNING THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND 20 Parliamentary oversight of the Church Commissioners 21 ANNEX 1: FORMER LORDS SPIRITUAL IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS 22 ANNEX 2: THE INFLUENCE OF LORDS SPIRITUAL ON THE OUTCOME OF VOTES IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS 24 Votes decided by the Lords Spiritual 24 Votes decided by current and former bishops 28 3 All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group FOREWORD The UK is more diverse than ever before. -

A Report of the House of Bishops' Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church Ho

Women Bishops in the Church of England? A report of the House of Bishops’ Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church House Publishing Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3NZ Tel: 020 7898 1451 Fax: 020 7989 1449 ISBN 0 7151 4037 X GS 1557 Printed in England by The Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Published 2004 for the House of Bishops of the General Synod of the Church of England by Church House Publishing. Copyright © The Archbishops’ Council 2004 Index copyright © Meg Davies 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or stored or transmitted by any means or in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without written permission, which should be sought from the Copyright Administrator, The Archbishops’ Council, Church of England, Church House, Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3NZ. Email: [email protected]. The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA, and are used by permission. All rights reserved. Contents Membership of the Working Party vii Prefaceix Foreword by the Chair of the Working Party xi 1. Introduction 1 2. Episcopacy in the Church of England 8 3. How should we approach the issue of whether women 66 should be ordained as bishops? 4. The development of women’s ministry 114 in the Church of England 5. Can it be right in principle for women to be consecrated as 136 bishops in the Church of England? 6. -

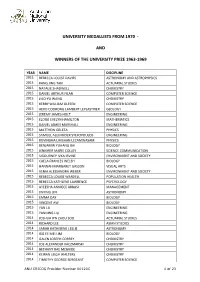

And Winners of the University Prize 1963-1969

UNIVERSITY MEDALLISTS FROM 1970 - AND WINNERS OF THE UNIVERSITY PRIZE 1963-1969 YEAR NAME DISCIPLINE 2015 REBECCA LOUISE DAVIES ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS 2015 KANG JING TAN ACTUARIAL STUDIES 2015 NATALIE SHADWELL CHEMISTRY 2015 DANIEL ARTHUR FILAN COMPUTER SCIENCE 2015 JIAO-YU WANG CHEMISTRY 2015 KERRY WILLIAM OLESEN COMPUTER SCIENCE 2015 AERO COORONG LAMBERT LEPLASTRIER GEOLOGY 2015 JEREMY JAMES HOLT ENGINEERING 2015 ELOISE EVELYN HAMILTON MATHEMATICS 2015 DANIEL JAMES MARSHALL ENGINEERING 2015 MATTHEW GELETA PHYSICS 2015 SAMUEL ALEXANDER STEFOPOULOS ENGINEERING 2015 RUVINDHA LAKSHAN LECAMWASAM PHYSICS 2015 BENJAMIN YUHANG BAI BIOLOGY 2015 JENNIFER MARIE COLLEY SCIENCE COMMUNICATION 2015 SIGOURNEY IVKA IRVINE ENVIRONMENT AND SOCIETY 2015 CAELA FRANCES WELSH BIOLOGY 2015 HANNAH MARGARET GASSON VISUAL ARTS 2015 XENIA ALESSANDRA WEBER ENVIRONMENT AND SOCIETY 2015 REBECCA LOUISE WARDELL POPULATION HEALTH 2015 REBECCA KATHLENE LAWRENCE PSYCHOLOGY 2015 AYEESHA ANNIECE ABBASI MANAGEMENT 2015 JINYING LIN ASTRONOMY 2015 EMMA DAY BIOLOGY 2015 VINCENT AW BIOLOGY 2015 YAN LU ENGINEERING 2015 YANNING LIU ENGINEERING 2014 JOSHUA IYN ZHOU SOO ACTUARIAL STUDIES 2014 RICHARD LEE ASIAN STUDIES 2014 SARAH KATHERINE LESLIE ASTRONOMY 2014 ISIS EE MEI LIM BIOLOGY 2014 GALEN JOSEPH CORREY CHEMISTRY 2014 JOE ALEXANDER KACZMARSKI CHEMISTRY 2014 BETHANY RAE MCBRIDE CHEMISTRY 2014 KEIRAN LEIGH WALTERS CHEMISTRY 2014 TIMOTHY GEORGE SERGEANT COMPUTER SCIENCE ANU CRICOS Provider Number 00120C 1 of 23 2014 JESSE ZHENGXI WU COMPUTER SCIENCE 2014 DANIEL JOHN AXTENS -

The Rt Revd Rachel Treweek

The Rt Revd Rachel Treweek Our ref: DB/10/20 Bishop of Gloucester The Bishops’ Office 13 October 2020 2 College Green, Gloucester, GL1 2LR [email protected] Tel: 01452 835511 Dear Sisters and Brothers Last week the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, IICSA, published its overarching investigation report into the Anglican Church in England and Wales, highlighting the failures of the Church of England regarding child sexual abuse. It is not comfortable reading, and neither should it be. This report brings together in one place the shocking failures of the Church, not least in often being more concerned with protecting reputation than focusing on the care of victims and survivors of abuse and responding with compassion. In many ways the sickening findings of this report come as no surprise given the content of the 2017 Gibb report investigating the Church’s response to Peter Ball’s abuse, followed in 2019 by the IICSA report on Peter Ball. I spoke out with lament and shame following these publications and now this final IICSA report highlights our failure as a Church to respond swiftly to some of the key recommendations made, which have been repeatedly voiced by victims and survivors of abuse. Listening, admittance of failure and expression of shock and sorrow are important but they are not enough. Action is required. Therefore, while I am glad that the report acknowledges significant changes which have been made over the years, it also shines a bright light on the systemic failures of governance structures and decision-making. This has undoubtedly hindered the much-needed action being taken swiftly at national level, including a process of satisfactory redress for victims and survivors of abuse, and the need for independence to be appropriately present in policies and procedures.