Entrepreneurial Recording Artists in Platform Capitalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEPTEMBER 10, 2021 Featuring: DEVIL’S REEF INFERI MR

NEW RELEASES FOR SEPTEMBER 10, 2021 featuring: DEVIL’S REEF INFERI MR. T EXPERIENCE Exclusively Distributed by DEVIL’S REEF A Whisper From The Cosmos LP/CD Street Date: September 10, 2021 ARTIST HOMETOWN: Frederick, MD KEY MARKETS: Chicago, Montreal, Los Angeles, Denver, Dallas FOR FANS OF: REVOCATION, OBSCURA, DEATH DEVIL’S REEF brings forth the perfect mix of death and thrash metal with A Whisper From The Cosmos. This EP packs a load of grooves laden with shreddy guitars a la the old school stylings of DEATH, but with the more modern approach of bands like OBSCURA and REVOCATION. ARTIST: DEVIL’S REEF MARKETING POINTS: TITLE: A Whisper From • Colored Vinyl The Cosmos • Limited edition of 600 copies LABEL: The Artisan Era • Legendary Canadian band CAT#: LP: AE-49-1 / CD: AE-49-2 FORMAT: LP/CD GENRE: Death Metal BOX LOT: 30/CD SRLP: LP: $39.98/CD: $13.98 UPC: LP: 123184004913 CD: 123184004920 EXPORT: No Restrictions TRACK LIST: 1. Quantum Strings 2. A Whisper From The Cosmos 3. Plague Uncovered 4. Ankida 5. Beyond Eternal Exclusively Distributed by Contact your sales rep: Mike Beer - [email protected] phone 414-672-9948 www.ildistro.com INFERI Vile Genesis LP/CD Street Date: September 10, 2021 ARTIST HOMETOWN: Nashville, TN KEY MARKETS: Chicago, Montreal, Los Angeles, Denver, Dallas FOR FANS OF: NECROPHAGIST, THE BLACK DAHLIA MURDER, ARCHSPIRE, OBSCURA, BEYOND CREATION, REVOCATION, FLESHGOD APOCALYPSE INFERI is back with their first full length in three years! Recorded, mixed, and mastered by Dave Otero (CATTLE DECAPITATION, ALLEGAEON, ARCHSPIRE), Vile Genesis shows that the band is more refined and mature than ever, focusing on over-the-top orchestra ARTIST: INFERI and strangely tasteful death metal riffs and grooves. -

OVFF Program Book Final

October 23-25, 2020 GUEST OF HONOR MISBEHAVIN' MAIDENS TOASTMASTER TOM SMITH HONORED LISTENERS DENNIS, SHARON, & KAITLIN PALMER INTERFILK GUEST JAMES MAHFFEY THE BROUGHT TO YOU BY AND STAFF WITH THE HELP THE OVFF COMMITTEE OF THE FRIENDS PEGASUS Mary Bertke OF OVFF COMMITTEE Linnea Davis Halle Snyder Alan Dormire Chair Emily Vazquez- Mark Freeman Lorene Andrews Erica Neely, Doug Cottrill Coulson Lisa Garrison Nancy Graf Evangelista Lori Coulson Elizabeth Gabrielle Gold Gary Hartman Steve Macdonald Leslie Davis Wilson Jade Ragsdale Judi Miller Co-Evangelista Trace Seamus Ragsdale Mary Frost-Pierson Trace Hagemann Hagemann Lyn Spring J. Elaine Richards Steve Shortino Kathy Hamilton David Tucker Jeff Tolliver Rob Wynne Jim Hayter Sally Kobee Steve Macdonald BJ Mattson Robin Nakkula Erica Neely Mark Peters Kat Sharp Roberta Slocumb OVFF 36 page 1 Chairman’s Welcome Welcome to NoVFF 2020. This has You are among friends. Enjoy! Welcome from been a very trying year for everyone on planet Lin Davis Earth. It seems only fair that by holding our Virtual NoVFF Con we allow Filkers from around the world to attend. Since you cannot come to us, we are sending NoVFF 2020 to you. ConChair OVFF 36 Just sit back at your favorite electronic device and link to us. There will be a wonderful Pegasus Concert, workshops and other Filk delights. You will get a chance to see the guests for 2021. They have agreed to attend and play for all in 2021. Please pay attention to our logo for this year. Created by Kat Sharp, it shows what we want to do with the COVID 19 virus. -

The Importance of the Catholic School Ethos Or Four Men in a Bateau

THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS OR FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health, and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ruth Joy August 2018 A dissertation written by Ruth Joy B.S., Kent State University, 1969 M.S., Kent State University, 2001 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2018 Approved by _________________________, Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Natasha Levinson _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Averil McClelland _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Catherine E. Hackney Accepted by _________________________, Director, School of Foundations, Leadership and Kimberly S. Schimmel Administration ........................ _________________________, Dean, College of Education, Health and Human Services James C. Hannon ii JOY, RUTH, Ph.D., August 2018 Cultural Foundations ........................ of Education THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS. OR, FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU (213 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Natasha Levinson, Ph. D. Dozens of academic studies over the course of the past four or five decades have shown empirically that Catholic schools, according to a wide array of standards and measures, are the best schools at producing good American citizens. This dissertation proposes that this is so is partly because the schools are infused with the Catholic ethos (also called the Catholic Imagination or the Analogical Imagination) and its approach to the world in general. A large part of this ethos is based upon Catholic Anthropology, the Church’s teaching about the nature of the human person and his or her relationship to other people, to Society, to the State, and to God. -

Bad Rhetoric: Towards a Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2012 Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Utley, Michael, "Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy" (2012). All Theses. 1465. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1465 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BAD RHETORIC: TOWARDS A PUNK ROCK PEDAGOGY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Michael M. Utley August 2012 Accepted by: Dr. Jan Rune Holmevik, Committee Chair Dr. Cynthia Haynes Dr. Scot Barnett TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ..........................................................................................................................4 Theory ................................................................................................................................32 The Bad Brains: Rhetoric, Rage & Rastafarianism in Early 1980s Hardcore Punk ..........67 Rise Above: Black Flag and the Foundation of Punk Rock’s DIY Ethos .........................93 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................109 -

Ilu Ustrat Io Nbyrobertmaes Ta S • Rmm Il Lu Strat Io N

JESUS SHAPED HOLES IN OUR HEARTS SINCE 1992 ILUUSTRATION BY ROBERT MAESTAS • RMMILLUSTRATION.PROSITE.COM VOLUME 23 | ISSUE 43 | OCTOBER 23-29, 2014 | FREE [2] OCTOBER 23-29 , 2014 WEEKLY ALIBI WEEKLY ALIBI OCTOBER 23-29 , 2014 [3] [4] OCTOBER 23-29 , 2014 WEEKLY ALIBI alibi VOLUME 23 | ISSUE 43 | OCTOBER 23-29 , 2014 EDITORIAL MANAGING EDITOR/MUSIC EDITOR: Samantha Anne Carrillo (ext. 243) [email protected] FILM EDITOR: Devin D. O’Leary (ext. 230) [email protected] FOOD EDITOR/FEATURES EDITOR : Ty Bannerman (ext. 260) [email protected] ARTS & LIT EDITOR/ WEB EDITOR : Lisa Barrow (ext. 267) [email protected] CALENDARS EDITOR/COPY EDITOR: Mark Lopez (ext. 239) [email protected] CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Cecil Adams, Steven Robert Allen, Captain America, Gustavo Arellano, Rob Brezsny, Shawna Brown, Suzanne Buck, Eric Castillo, David Correia, Erik Gamlem, Gail Guengerich, Nora Hickey, Zachary Kluckman, Kristi D. Lawrence, Ari LeVaux, Mark Lopez, August March, Genevieve Mueller, Amelia Olson, Geoffrey Plant, Benjamin Radford, Jeremy Shattuck, Mike Smith, M. Brianna Stallings, M.J. Wilde, Holly von Winckel PRODUCTION ART DIRECTOR: Jesse Schulz (ext. 229) [email protected] PRODUCTION MANAGER : Archie Archuleta (ext. 240) [email protected] GRAPHIC DESIGNER: Tasha Lujan (ext. 254) [email protected] STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER: Eric Williams [email protected] CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS: Ben Adams, Cutty Bage, ¡Brapola!, Michael Ellis, Stacy Hawkinson, KAZ, Robert Maestas, Julia Minamata, Tom Nayder, Ryan North, Jesse Phillips, Brian Steinhoff SALES SALES DIRECTOR: John Hankinson (ext. 265) [email protected] SENIOR DISPLAY ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE: Sarah Bonneau (ext. 235) [email protected] ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES: Valerie Hollingsworth (ext. 263) [email protected] Chelsea Kibbee (ext. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS MAY 17, 2021 | PAGE 1 OF 18 BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] INSIDE Grand Ole Opry Moves Toward The Old Normal THIS As U.S. Reemerges From COVID-19 ISSUE It likely won’t have the shelf life of Throwback Thursdays or In ideal Opry fashion, the lineup reflected a variety of styles Taco Tuesdays, but “full-capacity Friday night” had an oddly and eras. Lorrie Morgan opened with her chart-topping 1990 Sam Hunt’s ‘90’s’ special ring to it on May 14. single “Five Minutes,” and the rest of the talent parade fea- Breaks Out Grand Ole Opry announcer tured current hitmaker Michael Ray, >page 4 Bill Cody uncorked the phrase as Western vocal quartet Riders in the the WSM-AM Nashville show had Sky, comedian Aaron Weber, Nash- every ticket in the 4,400-seat Opry ville actor Charles Esten and new- House available for the first time comer Brittney Spencer, who sang Underwood, since March 10, 2020, when the a new song, “Sober & Skinny,” for the Aldean, Brooks coronavirus pandemic forced live first time in public. In Play entertainment off the stage. Some Spencer’s appearance was a >page 10 2,400 tickets were sold, according personal milestone, for she made to Opry vp/executive producer Dan her Opry debut. While she felt its Rogers, as the reboot coincided significance (she conceded that her with an unexpected bonus: Barely breathing was more pronounced Makin’ Tracks: 24 hours before the show’s start, the during “Sober” as she fought off a Drew Parker’s city of Nashville dropped face-mask case of nerves), she was still present ‘BP PBR’ Song mandates. -

![HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8672/how-black-is-black-metal-journalismus-nachrichten-von-heute-488672.webp)

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] nachrichten von heute Kevin Coogan - Lords of Chaos (LOC), a recent book-length examination of the “Satanic” black metal music scene, is less concerned with sound than fury. Authors Michael Moynihan and Didrik Sederlind zero in on Norway, where a tiny clique of black metal musicians torched some churches in 1992. The church burners’ own place of worship was a small Oslo record store called Helvete (Hell). Helvete was run by the godfather of Norwegian black metal, 0ystein Aarseth (“Euronymous”, or “Prince of Death”), who first brought black metal to Norway with his group Mayhem and his Deathlike Silence record label. One early member of the movement, “Frost” from the band Satyricon, recalled his first visit to Helvete: I felt like this was the place I had always dreamed about being in. It was a kick in the back. The black painted walls, the bizarre fitted out with inverted crosses, weapons, candelabra etc. And then just the downright evil atmosphere...it was just perfect. Frost was also impressed at how talented Euronymous was in “bringing forth the evil in people – and bringing the right people together” and then dominating them. “With a scene ruled by the firm hand of Euronymous,” Frost reminisced, “one could not avoid a certain herd-mentality. There were strict codes for what was accept- ed.” Euronymous may have honed his dictatorial skills while a member of Red Ungdom (Red Youth), the youth wing of the Marxist/Leninist Communist Workers Party, a Stalinist/Maoist outfit that idolized Pol Pot. All who wanted to be part of black metal’s inner core “had to please the leader in one way or the other.” Yet to Frost, Euronymous’s control over the scene was precisely “what made it so special and obscure, creating a center of dark, evil energies and inspiration.” Lords of Chaos, however, is far less interested in Euronymous than in the man who killed him, Varg Vikemes from the one-man group Burzum. -

The Fan Data Goldmine Sam Hunt’S Second Studio Full-Length, and First in Over Five Years, Southside Sales (Up 21%) in the Tracking Week

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayFEBRUARY 24, 2021 Page 1 of 30 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE The Fan Data Goldmine Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debuts at No. 1 on Billboard’s lionBY audienceTATIANA impressions, CIRISANO up 16%). Top Country• Spotify’s Albums Music chart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earnedLeaders 46,000 onequivalent the album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cordingStreaming to Nielsen Giant’s Music/MRC JessieData. Reyez loves to text, especially with fans.and Ustotal- Countryand Airplay Community No. 1 as “Catch” allows (Big you Machine to do that, Label especially Group) ascends Southside‘Audio-First’ marks Future: Hunt’s seconding No.a phone 1 on the number assigned through the celebrity when you’re2-1, not increasing touring,” 13% says to 36.6Reyez million co-manager, impressions. chart andExclusive fourth top 10. It followstext-messaging freshman LP startup Community and shared on her Mauricio Ruiz.Young’s “Using first every of six digital chart outletentries, that “Sleep you canWith- Montevallo, which arrived at thesocial summit media in No accounts,- the singer-songwriter makes to make sureout you’re You,” stillreached engaging No. -

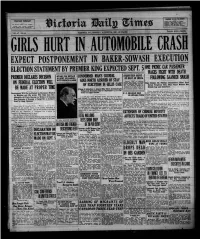

Expect Postponement in Barer Execution

WHERE T0_G0 TO-NIGHT WEATHER FORECAST Capitol—“The Making of0’M**ley rolembln—The Yankee Consul. _ . „ Dominion—"NWÿt Mfe In N.w Tort- Coliseum—"Lend Me YourWIfe.^ For 36 hours ending 5 pm, Tuesday: Victoria and vicinity — Southerly winds, cloudy and coo) with showers t>RICE FIVE CENTS VICTORIA, B.C., MONDAY, AUGUST 24, 1925 —16 PAGES VOL. 67 NO. 46 EXPECT POSTPONEMENT IN BARER EXECUTION ELECTION STATEMENT BY PREMIER KING EXPECTED SEPT, 5 mam SPEAKS FOR BRITAIN CONDEMNED MAN’S COUNSEL EIGHTEEN HURT PREMIER DECLARES DECISION IN DEBT EXCHANGES IN RIOT IN INDIA ti FOLLOWING SAANICH SMASH WITH FRENCH LEADER GOES NORTH ASSURED OF STAY Calcutta. Aug. 24.—Eighteen persons were Injured In serious rioting between Hindus and Mos Mi— Evelyn M. Phillips Unconscious Since Auto ON FEDERAL ELECTION WILL lems at Tagorgh. near here, to Struck Telephone Pole; Miss Jennie McGaw Has OF EXECUTION IN GILLIS CASE day. The Moslems charged the Hindus were carrying an Idol In a procession and played music aa Broken Leg and Collarbone. BE MADE AT PROPER TIE Filing of Intention to App May Have Automatically the procession passed a mosque. Postponed Execution 6 for September 4, it is Be- With a fractured skull sustained early yesterday morning in Government Will Not be Bushed by Discussion Started lieved in Legal Circles a motor accident on the West Saanich Road, Miss Evelyn Maude W. H. MILLMAN DIED Phillips, twenty-three, is waging a battle for life at the Royal by Meighen and His Aides; Will Take Into Con IN ONTARIO TOWN Jubilee Hospital. -

Life Is Hard's Indie Artist Guide to Music Marketing

Life is Hard’s Indie Artist Guide to Music Marketing The Importance of Music Marketing The biggest problem independent artists’ face is obscurity. You can have extraordinary songs, but if nobody is listening to them you will never achieve major success. It’s more than just having a great product or a catchy tune, you need to promote your brand. People need to get to know you, and they need to be inspired by you. As an artist, you need to connect with your audience in a personal way. The good news is we are living in amazing times where technology has made this process so much easier than in the past. The barriers to entry have been lowered so that you don’t have to rely on a producer or a major label to reach an audience. Within the past 16 years we have experienced the emergence of the internet, email, social media, DIY distribution channels, affordable home recording software and equipment, and many more tools at our disposal. So be encouraged and embrace the possibilities. The sky is the limit! One last thing on this topic… Don’t be overly protective of sharing your music, taking on an attitude of “they will have to pay to hear my music.” The main goal is to get it out there in the public domain, regardless of whether you have to sell it, or give it away. If your music is good, people will pay for it, regardless. You will make money! Copyrighting your Music Songwriters need to protect their music. -

The-DIY-Musician's-Starter-Guide.Pdf

Table of Contents Introduction 1 - 2 Music Copyright Basics 3 Compositions vs. Sound Recordings 4 - 5 Being Your Own Record Label 6 Being Your Own Music Publisher 7 Wearing Multiple Hats: Being Four Income Participants 8 - 12 Asserting Your Rights and Collecting Your Royalties 13 - 18 Conclusion 19 Legal Notice: This guide is solely for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal or other professional advice. © 2017 TuneRegistry, LLC. All Rights Reserved. 0 Introduction A DIY musician is a musician who takes a “Do-It-Yourself” approach to building a music career. That is, a DIY musician must literally do everything themselves. A DIY musician might have a small network of friends, family, collaborators, and acquaintances that assists them with tasks from time to time. However, virtually all decisions, all failures, and all successes are a result of the DIY musician’s capabilities and efforts. Being a DIY musician can be overwhelming. A DIY musician has a lot on their plate including: writing, recording, promoting, releasing, and monetizing new music; planning, marketing, and producing tours; reaching, building, and engaging a fan base; managing social media; securing publicity; and so much more. A DIY musician may hire a manager and/or attorney to assist them with their career, but they are not signed to or backed by a record label or a music publishing company. Just three decades ago it was virtually impossible for the average DIY musician to get their music widely distributed without the help of a record company. While some DIY musicians were successful in releasing music locally and developing local fan bases, widespread distribution and reach was hard to achieve. -

It's Jerry's Birthday Chatham County Line

K k JULY 2014 VOL. 26 #7 H WOWHALL.ORG KWOW HALL NOTESK g k IT’S JERRY’S BIRTHDAY On Friday, August 1, KLCC and Dead Air present an evening to celebrate Jerry Garcia featuring two full sets by the Garcia Birthday Band. Jerry Garcia, famed lead guitarist, songwriter and singer for The Grateful Dead and the Jerry Garcia Band, among others, was born on August 1, 1941 in San Francisco, CA. Dead.net has this to say: “As lead guitarist in a rock environment, Jerry Garcia naturally got a lot of attention. But it was his warm, charismatic personality that earned him the affection of millions of Dead Heads. He picked up the guitar at the age of 15, played a little ‘50s rock and roll, then moved into the folk acoustic guitar era before becoming a bluegrass banjo player. Impressed by The Beatles and Stones, he and his friends formed a rock band called the Warlocks in late 1964 and debuted in 1965. As the band evolved from being blues-oriented to psychedelic/experi- mental to adding country and folk influences, his guitar stayed out front. His songwriting partnership with Robert Hunter led to many of the band’s most memorable songs, including “Dark Star”, “Uncle John’s Band” and the group’s only Top 10 hit, “Touch of Grey”. Over the years he was married three times and fathered four daughters. He died of a heart attack CHATHAM COUNTY LINE in 1995.” On Sunday, July 27, the Community Tightrope also marks a return to Sound Fans have kept the spirit of Jerry Garcia alive in their hearts, and have spread the spirit Center for the Performing Arts proudly wel- Pure Studios in Durham, NC, where the and the music to new generations.