An Interface Between Ecological Theory and Statistical Modelling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resilience of Alternative States in Spatially Extended Ecosystems

RESEARCH ARTICLE Resilience of Alternative States in Spatially Extended Ecosystems Ingrid A. van de Leemput*, Egbert H. van Nes, Marten Scheffer Department of Environmental Sciences, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands * [email protected] Abstract Alternative stable states in ecology have been well studied in isolated, well-mixed systems. However, in reality, most ecosystems exist on spatially extended landscapes. Applying ex- isting theory from dynamic systems, we explore how such a spatial setting should be ex- pected to affect ecological resilience. We focus on the effect of local disturbances, defining resilience as the size of the area of a strong local disturbance needed to trigger a shift. We show that in contrast to well-mixed systems, resilience in a homogeneous spatial setting does not decrease gradually as a bifurcation point is approached. Instead, as an environ- OPEN ACCESS mental driver changes, the present dominant state remains virtually ‘indestructible’, until at Citation: van de Leemput IA, van Nes EH, Scheffer a critical point (the Maxwell point) its resilience drops sharply in the sense that even a very M (2015) Resilience of Alternative States in Spatially Extended Ecosystems. PLoS ONE 10(2): e0116859. local disturbance can cause a domino effect leading eventually to a landscape-wide shift to doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116859 the alternative state. Close to this Maxwell point the travelling wave moves very slow. Under Academic Editor: Emanuele Paci, University of these conditions both states have a comparable resilience, allowing long transient co-occur- Leeds, UNITED KINGDOM rence of alternative states side-by-side, and also permanent co-existence if there are mild Received: April 11, 2014 spatial barriers. -

NEW DATA ABOUT MOSSES on the SVALBARD GLACIERS Olga

NEW DATA ABOUT MOSSES ON THE SVALBARD GLACIERS Olga Belkina Polar-Alpine Botanical Garden-Institute, Kola Science Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Apatity, Murmansk Province, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] Rapid melting and retreat of glaciers in the Arctic is a cause of sustainable long‐ In Svalbard moss populations were found on 9 glaciers. In 2012, during re‐examination of the populations a few term existence of ablation zone on them. Sometimes these areas are the habitats In 2007 B.R.Mavlyudov collected one specimen on individuals of Bryum cryophilum Mårtensson and some plants of some mosses partly due to good availability of water and cryoconite Bertilbreen (Paludella squarrosa (Hedw.) Brid.) and of Sanionia uncinata were found among H. polare shoots in substratum. 14 species were found in this unusual habitat on Alaska and Iceland: some specimens on Austre Grønfjordbreen (Ceratodon some large cushions. Therefore the next stage of cushion Andreaea rupestris Hedw., Ceratodon purpureus (Hedw.) Brid., Ditrichum purpureus (Hedw.) Brid., Warnstorfia sarmentosa succession had begun –emergence of a di‐ and multi‐species flexicaule (Schwaegr.) Hampe, Pohlia nutans (Hedw.) Lindb., Polytrichum (Wahlenb.) Hedenäs, Sanionia uncinata (Hedw.) community. A similar process was observed earlier on the juniperinum Hedw. (Benninghoff, 1955), Racomitrium fasciculare (Hedw.) Brid. Loeske, Hygrohypnella polare (Lindb.) Ignatov & bone of a mammal that was lying on the same glacier. (=Codriophorus fascicularis (Hedw.) Bendarek‐Ochyra et Ochyra) (Shacklette, Ignatova.). Ceratodon purpureus settled in center of almost spherical 1966), Drepanocladus berggrenii (C.Jens.) Broth. (Heusser, 1972), Racomitrium In 2009 populations of two latter species were studied cushion of Sanionia uncinata on the both butt‐ends of the crispulum var. -

Meta-Ecosystems: a Theoretical Framework for a Spatial Ecosystem Ecology

Ecology Letters, (2003) 6: 673–679 doi: 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00483.x IDEAS AND PERSPECTIVES Meta-ecosystems: a theoretical framework for a spatial ecosystem ecology Abstract Michel Loreau1*, Nicolas This contribution proposes the meta-ecosystem concept as a natural extension of the Mouquet2,4 and Robert D. Holt3 metapopulation and metacommunity concepts. A meta-ecosystem is defined as a set of 1Laboratoire d’Ecologie, UMR ecosystems connected by spatial flows of energy, materials and organisms across 7625, Ecole Normale Supe´rieure, ecosystem boundaries. This concept provides a powerful theoretical tool to understand 46 rue d’Ulm, F–75230 Paris the emergent properties that arise from spatial coupling of local ecosystems, such as Cedex 05, France global source–sink constraints, diversity–productivity patterns, stabilization of ecosystem 2Department of Biological processes and indirect interactions at landscape or regional scales. The meta-ecosystem Science and School of perspective thereby has the potential to integrate the perspectives of community and Computational Science and Information Technology, Florida landscape ecology, to provide novel fundamental insights into the dynamics and State University, Tallahassee, FL functioning of ecosystems from local to global scales, and to increase our ability to 32306-1100, USA predict the consequences of land-use changes on biodiversity and the provision of 3Department of Zoology, ecosystem services to human societies. University of Florida, 111 Bartram Hall, Gainesville, FL Keywords 32611-8525, -

Spatial Ecology and Modeling of Fish Populations - FAS 6416

Spatial Ecology and Modeling of Fish Populations - FAS 6416 1 Overview Spatial approaches to fisheries management are increasingly of interest the conservation and management of fish populations; and spatial research on fish populations and fish ecology is becoming a cornerstone of fisheries research. This course explores spatial ecology concepts, population dynamics models, examples of field data, and computer simulation tools to understand the ecological origin of spatial fish populations and their importance for fisheries management and conservation. The course is suitable for students who are interested in an interdisciplinary research field that draws as much from ecology as from fisheries management. 2 credits Spring Semester Face-to-face Location TBD with course website: http://elearning.ufl.edu/ The course is intended to provide students with different types of models and concepts that explain the spatial distribution of fish at different spatial and temporal scales. The course is new and evolving, and contains structured elements as well as exploratory exercises and discussions that are aimed at providing students with new perspectives on the dynamics of fish populations. Course Prerequisites: Graduate student status in Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences (or related, as determined by instructor). Interested graduate students in Wildlife Ecology are welcome. Instructor: Dr. Juliane Struve, [email protected]. SFRC Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Rm. 34, Building 544. Telephone: 352-273-3632. Cell Phone: 352-213-5108 Please use the Canvas message/Inbox feature for fastest response. Office hours: Tuesdays, 3-5pm or online by appointment Textbook(s) and/or readings: The course does not have a designated text book. Reading materials will be assigned for every session and typical consist of 1-2 classic and recent papers. -

Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author's Permission) ,, l • ...J ..... The Disjunct Bryophyte Element of the Gulf of St. Lawrence Region: Glacial and Postglacial Dispersal and Migrational Histories By @Rene J. Belland B.Sc., M.Sc. A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Biology Memorial University of Newfoundland December, 1Q84 St. John's Newfoundland Abstract The Gulf St. Lawrence region has a bryophyte flora of 698 species. Of these 267 (38%) are disjunct to this region from western North America, eastern Asia, or Europe. The Gulf of St. Lawrence and eastern North American distributions of the disjuncts were analysed and their possible migrational and dispersal histories during and after the Last Glaciation (Wisconsin) examined. Based on eastern North American distribution patterns, the disjuncts fell into 22 sub elements supporting five migrational/ dispersal histories or combinations of these : (1) migration from the south, (2) migration from the north, (3) migration from the west, (4) survival in refugia, and (5) introduction by man. The largest groups of disjuncts had eastern North American distributions supporting either survival of bryophytes in Wisconsin ice-free areas of the Gulf of St. Lawrence or postglacial migration to the Gulf from the south. About 26% of the disjuncts have complex histories and their distributions support two histories. These may have migrated to the Gulf from the west and/or north, or from the west and/or survived glaciation in Gulf ice-free areas. -

Community Stability and Turnover in Changing Environments Kevin Liautaud

Community stability and turnover in changing environments Kevin Liautaud To cite this version: Kevin Liautaud. Community stability and turnover in changing environments. Biodiversity and Ecology. Université Paul Sabatier - Toulouse III, 2020. English. NNT : 2020TOU30264. tel- 03236079 HAL Id: tel-03236079 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03236079 Submitted on 26 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THTHESEESE`` En vue de l’obtention du DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE´ DE TOULOUSE D´elivr´epar : l’Universit´eToulouse 3 Paul Sabatier (UT3 Paul Sabatier) Pr´esent´eeet soutenue le 13 Mars 2020 par : Kevin LIAUTAUD Community stability and turnover in changing environments JURY THEBAUD Christophe Professeur d’Universit´e Pr´esident du Jury BARABAS Gyorgy¨ Professeur Assistant Membre du Jury POGGIALE Jean-Christophe Professeur d’Universit´e Membre du Jury THEBAULT Elisa Charg´eede Recherche Membre du Jury SCHEFFER Marten Directeur de Recherche Membre du Jury LOREAU Michel Directeur de Recherche Membre du Jury Ecole´ doctorale et sp´ecialit´e: -

Landscapes of Fear: Spatial Patterns of Risk

TREE 2486 No. of Pages 14 Review Landscapes of Fear: Spatial Patterns of Risk Perception and Response 1, ,@ 2,3,5 1,5 4,5 Kaitlyn M. Gaynor , * Joel S. Brown, Arthur D. Middleton, Mary E. Power, and 1 Justin S. Brashares Animals experience varying levels of predation risk as they navigate heteroge- Highlights neous landscapes, and behavioral responses to perceived risk can structure Recent technological advances have provided unprecedented insights into ecosystems. The concept of the landscape of fear has recently become central the movement and behavior of animals to describing this spatial variation in risk, perception, and response. We present on heterogeneous landscapes. Some studies have indicated that spatial var- a framework linking the landscape of fear, defined as spatial variation in prey iation in predation risk plays a major perception of risk, to the underlying physical landscape and predation risk, and role in prey decision making, which can to resulting patterns of prey distribution and antipredator behavior. By disam- ultimately structure ecosystems. biguating the mechanisms through which prey perceive risk and incorporate The concept of the ‘landscape of fear’ fear into decision making, we can better quantify the nonlinear relationship was introduced in 2001 and has been between risk and response and evaluate the relative importance of the land- widely adopted to describe spatial var- iation predation risk, risk perception, scape of fear across taxa and ecosystems. and response. However, increasingly divergent interpretations of its meaning Introduction and application now cloud under- The risk of predation plays a powerful role in shaping behavior of fearful prey, with conse- standing and synthesis, and at least 15 distinct processes and states have quences for individual physiology, population dynamics, and community interactions [1,2]. -

Spatial Ecology of Territorial Populations

Spatial ecology of territorial populations Benjamin G. Weinera, Anna Posfaib, and Ned S. Wingreenc,1 aDepartment of Physics, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544; bSimons Center for Quantitative Biology, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY 11724; and cLewis–Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544 Edited by Nigel Goldenfeld, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Urbana, IL, and approved July 30, 2019 (received for review July 9, 2019) Many ecosystems, from vegetation to biofilms, are composed of and penalize niche overlap (25), but did not otherwise struc- territorial populations that compete for both nutrients and phys- ture the spatial interactions. All these models allow coexistence ical space. What are the implications of such spatial organization when the combination of spatial segregation and local interac- for biodiversity? To address this question, we developed and ana- tions weakens interspecific competition relative to intraspecifc lyzed a model of territorial resource competition. In the model, competition. However, it remains unclear how such interactions all species obey trade-offs inspired by biophysical constraints on relate to concrete biophysical processes. metabolism; the species occupy nonoverlapping territories, while Here, we study biodiversity in a model where species interact nutrients diffuse in space. We find that the nutrient diffusion through spatial resource competition. We specifically consider time is an important control parameter for both biodiversity and surface-associated populations which exclude each other as they the timescale of population dynamics. Interestingly, fast nutri- compete for territory. This is an appropriate description for ent diffusion allows the populations of some species to fluctuate biofilms, vegetation, and marine ecosystems like mussels (28) or to zero, leading to extinctions. -

Introduction to the Special Issue on Spatial Ecology

International Journal of Geo-Information Editorial Space-Ruled Ecological Processes: Introduction to the Special Issue on Spatial Ecology Duccio Rocchini 1,2,3 1 University of Trento, Center Agriculture Food Environment, Via E. Mach 1, 38010 S. Michele all’Adige (TN), Italy; [email protected] 2 University of Trento, Centre for Integrative Biology, Via Sommarive, 14, 38123 Povo (TN), Italy 3 Fondazione Edmund Mach, Department of Biodiversity and Molecular Ecology, Research and Innovation Centre, Via E. Mach 1, 38010 S. Michele all’Adige (TN), Italy Received: 12 December 2017; Accepted: 23 December 2017; Published: 2 January 2018 This special issue explores most of the scientific issues related to spatial ecology and its integration with geographical information at different spatial and temporal scales. Papers are mainly related to challenging aspects of species variability over space and landscape dynamics, providing a benchmark for future exploration on this theme. The need for a spatial view in Ecology is a fact. Dealing with ecological changes over space and time represents a long-lasting theme, now faced by means of innovative techniques and modelling approaches (e.g., Chaudhary et al. [1], Palmer [2], Rocchini [3]). This special issue explores some of them, with challenging ideas facing different components of spatial patterns related to ecological processes, such as: (i) species variability over space [4–11]; and (ii) landscape dynamics [12,13]. Concerning biodiversity variability over space, key spatial datasets are needed to fully investigate biodiversity change in space and time, as shown by Geri et al. [7], who carried out innovative procedures to recover and properly map historical floristic and vegetation data for biodiversity monitoring. -

Pattern and Process Second Edition Monica G. Turner Robert H. Gardner

Monica G. Turner Robert H. Gardner Landscape Ecology in Theory and Practice Pattern and Process Second Edition L ANDSCAPE E COLOGY IN T HEORY AND P RACTICE M ONICA G . T URNER R OBERT H . G ARDNER LANDSCAPE ECOLOGY IN THEORY AND PRACTICE Pattern and Process Second Edition Monica G. Turner University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Zoology Madison , WI , USA Robert H. Gardner University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science Frostburg, MD , USA ISBN 978-1-4939-2793-7 ISBN 978-1-4939-2794-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4939-2794-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015945952 Springer New York Heidelberg Dordrecht London © Springer-Verlag New York 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

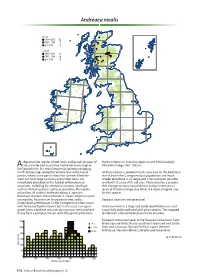

Andreaea Nivalis

Andreaea nivalis Britain 1990–2013 12 1950–1989 7 pre-1950 4 Ireland 1990–2013 0 1950–1989 0 pre-1950 0 characteristic species of wet rocks and gravels in areas of Nardia compressa, Scapania uliginosa and Pohlia ludwigii. Alate snow-lie and associated meltwater burns high in Altitudinal range: 880–1340 m. the Scottish hills. It is most frequently found on dripping, north-facing crags along the ‘cornice line’ at the top of Andreaea nivalis is abundant in its core area on the Ben Nevis corries, where snow persists into the summer. Here the massif and in the Cairngorms but populations are much moss can form large cushions and on Ben Nevis it is smaller elsewhere in its range and it has not been possible remarkably abundant in this habitat with numerous to refind it at some of its old sites. There must be a concern associates, including Deschampsia cespitosa, Saxifraga that changes in snow accumulation and persistence as a stellaris, Anthelia julacea, Lophozia opacifolia, Marsupella result of climate change may affect the more marginal sites sphacelata, M. stableri, Andreaea alpina, A. rupestris, for this species. Ditrichum zonatum, Kiaeria falcata, K. starkei, Polytrichastrum sexangulare, Racomitrium lanuginosum and, rarely, Dioicous; capsules are occasional. Oedipodium griffithianum. In the Cairngorms it often occurs with Andreaea frigida in burns but it also occurs on open Andreaea nivalis is a large and easily identifiable moss and gravel areas which are very wet during snow melt and here is not likely to be confused with other species. The mapped it may form a complex mosaic with Marsupella sphacelata, distribution is therefore believed to be accurate. -

THE ANDEAN SPECIES of PILEA by Ellsworth P. Killip INTRODUCTION

THE ANDEAN SPECIES OF PILEA By Ellsworth P. Killip INTRODUCTION Pilea is by far the largest genus of Urticaceae. Weddell in his final monograph 1 of the family recognized 159 species as valid, about 50 of which were said to occur in the Andes of South America. That these species had a very limited range of distribution was indicated by the fact that more than 30 were known from only a single collection and that only 9 of the others were in any sense widely distributed in the Andean countries. Two, P. microphyUa and P. pubescens, occurred throughout the American Tropics, and P. kyalina and P. dendrophUa extended eastward in South America. In the 50 years following the publication of this monograph only 10 species were described from the Andean region. Because of the large number of specimens of Pilea collected by expeditions to the Andes sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution, the New York Botanical Garden, the Gray Herbarium and the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, the Field Museum of Natural History, and the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, which were submitted to me for identification but which could not be assigned to any known species, I began the preparation of a mono- graph of all the Andean species. This was completed in 1935 but unfortunately could not be printed in its entirety at that time. Instead, a greatly abridged paper was published,2 which contained a key to all the Andean species, descriptions of 30 new ones, and a few changes of name and of rank. In this there was no opportunity to present descriptions of the earlier species or to discuss their synonymy.