The Case of Nusret's Sexualized Performative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universidad Peruana De Ciencias Aplicadas Facultad

Caracterización de los procesos de consumo de los K- Dramas y videos musicales de K-Pop, y su incidencia en la construcción de la identidad y formas de socialización en la comunidad Hallyu de Lima. Una aproximación desde los fenómenos de audiencia en K-Dramas Descendants of the Sun y Goblin: The Lonely and Great God, y los fenómenos de tendencia musical de los grupos BIG BANG y Bangtan Boys; Beyond The Scene a.k.a BTS Item Type info:eu-repo/semantics/bachelorThesis Authors Mosquera Anaya, Heidy Winie Publisher Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC) Rights info:eu-repo/semantics/openAccess; Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Download date 10/10/2021 11:56:20 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10757/648589 UNIVERSIDAD PERUANA DE CIENCIAS APLICADAS FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIONES PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO DE COMUNICACIÓN AUDIOVISUAL Y MEDIOS INTERACTIVOS Caracterización de los procesos de consumo de los K-Dramas y videos musicales de K-Pop, y su incidencia en la construcción de la identidad y formas de socialización en la comunidad Hallyu de Lima. Una aproximación desde los fenómenos de audiencia en K-Dramas Descendants of the Sun y Goblin: The Lonely and Great God, y los fenómenos de tendencia musical de los grupos BIG BANG y Bangtan Boys; Beyond The Scene a.k.a BTS. TESIS Para optar el título profesional de Licenciado en Comunicación Audiovisual y Medios Interactivos AUTOR(A) Mosquera Anaya, Heidy Winie (0000-0003-4569-9612) ASESOR(A) Calderón Chuquitaype, Gabriel Raúl (0000-0002-1596-8423) Lima, 01 de Junio de 2019 DEDICATORIA A mis padres Abraham y Luz quienes con su amor, paciencia y esfuerzo me han permitido llegar a cumplir hoy un sueño más. -

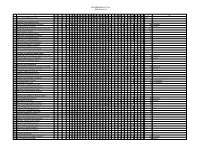

2020 MAQHA Select Points 2020 Final Points Horses Name

2020 MAQHA Select Points 2020 Final Points A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z AA ABAC AD AE AF AJ AK 1 Horses Name/Exhibitors Name HC1 HC2 HC3 D1 D2 D3 D4 Y1 Y2 Y3 S1 S2 S3 S4 G1 G2 G3 G4 L1 L2 L3 L4 F1 F2 F3 F4 G5A1 A2 A3 P4Total 2 3 Amateur Select Showmanship 4 Splash O Moonlite/Barbara Chambers 4 4 3 9 9 9 8 7 9 9 9 7 5 6 6 9 9 9 8 8 9 9 165 Champion 5 The Sheik/Denise Hoffman 5 5 5 3 3 3 9 7 7 7 6 6 5 7 4 5 5 3 6 8 8 117 Reserve 6 PSU His Rhythm Rocks/Sandy Slocum-Lipscomb 1 2 4 5 7 8 7 8 8 8 6 8 8 6 7 9 6 6 114 7 Moonwalk/Christi Free 2 2 2 1 5 2 4 3 1 1 3 3 4 7 4 7 7 5 63 8 Been Alota Fun/Jeannie Hotard 3 3 3 2 5 1 5 5 2 2 2 2 0 3 2 1 41 9 Relentless Chase/Christine Schlecht 1 1 1 1 3 2 1 2 4 4 4 4 0 0 0 0 3 3 3 37 10 Shifty Doc Riddle/Debbie Purvis 4 4 4 3 1 1 0 6 23 11 Defination Of Lazy/Lisa Weaver 0 0 0 0 1 3 3 1 5 2 4 2 21 12 Talkaboutasweetchip/Debbie Wells 2 3 3 1 2 2 2 15 13 Certainly A Goodbar/Lisa Weaver 2 1 2 5 14 Bae Bae R Smokin/Aprille Watts 1 1 1 3 15 Shiney Red Kadillac/Sheila Schmidt 0 0 0 0 0 16 17 Amateur Select Hunter Under Saddle 18 PSU His Rhythm Rocks/Samdy Slocum-Lipscomb 3 1 1 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 39 Champion 19 Relentles Chase/Christine Schlecht 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 1 18 Reserve 20 Shifty Doc Riddle/Debbie Purvis 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 9 21 22 Amateur Select Equitation 23 PSU His Rhythm Rocks/Sandy Slocum-Lipscomb 3 3 4 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 36 Champion 24 Relentless Chase/Christine Schlecht 1 2 1 1 2 2 2 2 14 Reserve 25 Willie B Caaned/Lisa Marshall 4 4 3 3 14 26 Shifty Doc Riddle/Debbie Purvis -

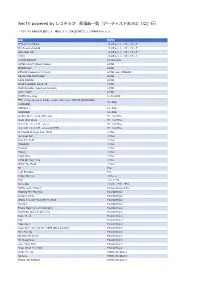

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

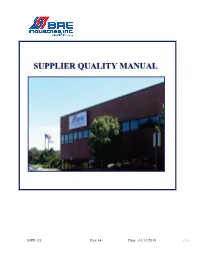

Bae Quality Guidelines for Suppliers

SUPPLIER QUALITY MANUAL MPP- 05 Rev.14 Date: 03/13/2019 - 1 - Table of Contents 1. Introduction 4 1.1 Preface 4 1.2 Purpose and Scope 4 2. Supplier Qualification 4 2.1 Supplier Approval & Evaluation 4 2.2 Supplier Selection 5 2.3 Supplier Development 5 3. Prototype/Pre-Approved Product Requirements 5 3.1 Scope and Definition 5 3.2 Procedure 5 3.2.1 Quotation Requirements 6 3.2.2 Design Requirements 7 3.2.3 Quality Requirements 8 3.3 Control Plan for Prototypes 8 4. Quality Planning 8 4.1 Specifications and Requirements 8 4.2 Process Flow Chart 9 4.3 Feasibility Analysis 9 4.4 Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) 9 MPP- 05 Rev.14 Date: 03/13/2019 - 2 - 4.5 Control Plans 10 4.6 Process Instructions 10 4.7 Planning of Tooling and Equipment 11 4.8 Gauge Measuring and Test Equipment 11 4.9 Preliminary Process Capability 11 4.10 Packaging Planning 12 4.10.1 Labeling 12 4.10.2 Shipment Documents 13 4.10.3 Special Packing Labels 13 4.11 Quality Assurance of Sub-Contracted Parts 13 5. Parts Approval & Initial Samples 14 5.1 Definitions 14 5.2 Procedure 14 5.2.1 Production Trial Run 14 5.2.2 Identification of Initial Samples 14 5.3 Productions Part Approval Process (PPAP) 15 5.3.1 Requirements . 15 5.3.2 Expectations of Launch Readiness 16 5.4 Approval 16 5.5 Tool Invoices 17 MPP- 05 Rev.14 Date: 03/13/2019 - 3 - 5.6 Tool Tag 17 5.6.1 Tool Tag Template 17 6. -

Download Bigbang Made Full Album Japanese K2nblog Zinnia Magenta

download bigbang made full album japanese k2nblog Zinnia Magenta. Download Musik, MV/PV Jepang & Korea Full Version + Drama Korea Subtittle Indonesia. Newest Post. Download [Album] BIGBANG - MADE. BIGBANG – MADE [FULL ALBUM] Release Date: 2016.12.13 Genre: Rap / Hip-hop, Ballad, Dance, Folk, Rock Language: Korean Bit Rate: MP3-320kbps + iTunes Plus AAC M4A Big Bang’s tenth anniversary project comes to an end with the last album of the Made series. Besides the Made singles, such as Bang Bang Bang, Loser, Bae Bae and “Let’s Not Fall in Love,” the album also features three new tracks, namely the double title numbers FXXK IT and Last Dance, as well as Girlfriend written by G-Dragon, TOP and YG in-house producer Teddy. Track List: 01. 에라 모르겠다 (FXXK IT) *Title 02. LAST DANCE *Title 03. GIRLFRIEND 04. 우리 사랑하지 말아요 (LET’S NOT FALL IN LOVE) 05. LOSER 06. BAE BAE 07. 뱅뱅뱅 (BANG BANG BANG) 08. 맨정신 (SOBER) 09. IF YOU 10. 쩔어 (ZUTTER) (GD & T.O.P) 11. WE LIKE 2 PARTY. Download Album File: BIGBANG – MADE [Zinnia Magenta].rar Size: 95.9 MB. Download bigbang made full album japanese k2nblog. BIG BANG Albums Download. BIGBANG – Alive (Monster Edition) 1. Still Alive 2. MONSTER 3. FANTASTIC BABY 4. Blue 5. Love Dust 6. FEELING 7. Ain't No Fun 8. BAD BOY 9. EGO 10. Wings 11. Bingle Bingle 12. Haru Haru (Japanese ver.) DOWNLOAD. BIGBANG - Still Alive Special Edition. 1. Still Alive 2. MONSTER 3. Feeling 4. FANTASTIC BABY 5. BAD BOY 6. Blue 7. Round and Round 빙글빙글 (Bingeul Bingeul) 8. -

Ismert K-Pop Előadók Dalai 5

Ismert előadók híresebb dalai - 5 Írta: Edina holmes Mi is az a K-pop? VIII. Zene k-pop 094 Ezzel a résszel befejezzük az ismerkedést a k-pop dalokkal az első generációtól mostanáig. A változatosság érdekében nemcsak egy generációt veszünk végig a cikkben, hanem az összesből sze- mezgetünk időrendi sorrendben. Vágjunk is bele! A dalokat meghallgathatjátok az edinaholmes. com-on előadók szerinti lejátszólistákban. Psy Aktív évek: 2001-napjainkig Ügynökség: P Nation Híresebb dalai: Bird, The End, Champion, We Are The One, Delight, Entertainer, Right Now, Shake It, Gangnam Style, Gentleman, Daddy, Napal Baji, New Face, I Luv It Big Bang Sechs Kies Tagok száma: 4 J. Y. Park Tagok száma: 4 Aktív évek: 2006-napjainkig Aktív évek: 1994-napjainkig Aktív évek: 1997-2000; 2016-napjainkig Lee Hyori Ügynökség: YG Ügynökség: JYP Ügynökség: YG Aktív évek: 2003-napjainkig Híresebb dalaik: Lies, Last Farewell, Haru Haru, Híresebb dalai: Don’t Leave Me, Elevator, Híresebb dalaik: School Byeolgok, Ügynökség: Esteem Sunset Glow, Tonight, Love Song, Blue, Bad Boy, She Was Pretty, Honey, Kiss, Your House, Pom Saeng Pom Sa, Chivalry, Road Fighter, Híresebb dalai: 10 Minutes, Toc Toc Toc, Fantastic Baby, Monster, Loser, Bae Bae, Someone Else, You’re The One, Who’s Your Reckless Love, Couple, Com’ Back, Hunch, U-Go-Girl, Swing, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, Bang Bang Bang, If You, Let’s Not Fall In Love, Mama?, I’m So Sexy, Fever, When We Disco Three Words, Be Well, Something Special Miss Korea, Bad Girls, Seoul, Black Fxxk It, Last Dance, Flower Road AniMagazin Tartalomjegyzék △ Zene k-pop 095 Legendás K-pop zenék - vol 8. -

The Homosexuals Q U Homose S H T

Fringe, the 2016 Outstanding performing arts as an actor, production. She was in the Access Award at Melbourne singer and producer. London and Sydney seasons The Farce is popular enough, when it comes to revivals. In This is where I’ve wound up setting my BIOGRAPHIES Darwin Festival: Highway of State Theatre Company and National Studio program; for Fringe, and a 2015 Nominee of Working Title’s production the last few years in Australia we’ve seen plays like Noises farce: square in the cross-fire of a culture Declan Greene Lost Hearts; for the National Belvoir: The Sapphires, which Jetpack Theatre Collective: for GLOBE LGBTI Artist of the Simon Corfield of Billy Elliot, for which she Off, A Flea In Her Ear, and One Man, Two Guvners hit stages war where outrage is currency, feelings are Playwright Institute of Dramatic Art: Big toured nationally,BIOGRAPHIES and to South How. Dare., co-written for Declan Greene is a theatre- Love, Shopping and Fucking, Korea and London’s Barbican Sydney Fringe Festival; Year. Mama has worked with Kim received a Helpmann Award to mass delight. But as far as new playwriting goes, over facts, sensitivities are ignored, atonement Brook Andrew, Phillip Adams Simon’s acting credits include: for Best Female Actor in a maker based in Melbourne. His After Dinner and The Winter’s Theatre; with Melbourne for Montague Basement: BalletLab, is a proud alumni of for Griffin: Motortown, Orestes Musical, the Sydney Theatre GRIFFIN THEATRE COMPANY IN ASSOCIATION the last few decades the Farce has gone the way of the is impossible, and simplistic buzz- words previous works as a playwright Tale; and for the Western Theatre Company: National Kaleidoscope, Telescope; Monash Uni Student Theatre, 2.0, Tattoo; for Belvoir: Bliss; for Critics Award for the Judith WITH MALTHOUSE THEATRE PRESENTS Passion Play, the Verse Drama, and Commedia dell’Arte.. -

Talbot Brothers of Bermuda Ziggi Talent Marion Talley

TALBOT BROTHERS OF BERMUDA A group of calypso, the Archie brothers (singer, acoustic guitar, harmonica, Autrie acoustic guitar, harmonica, Bryan, tipple, Ross, electric guitar and roy Talbot, bass and cousin Mandy Mandius accordion active years 1942-1980. Lp ABC-156 “Talbet Brothers”, 1956. Calypo Chacha / ch ZIGGI TALENT 88608. 1955 Dec 26888 Cheek to cheek chachacha/ ch MARION TALLEY Nevada, Mississippi 12/20/1906 - 1/3/1983. American operates coloratura soprano. 5/1/30 V BVE 59778 Mirame asi/r ESF THE TARIERS It was a vocal group specialized in folk music. Lp DL-4538 “Gather room of TT”, 1964. Guantanamera / r JF TARRAGANO ORCHESTRA Lp Kapp- ML-7511/MS 7511 “Surprise Party latin style”, 1960. In a little Spanish town chachacha / ch Rockambo / mb Mambo jambo / mb Mama Inez / r MS Tabu / r ML Lp London HA-R-2399/ SAHR 6199 “Surprise Party latin style”, 1960. In a little Spanish town chachacha / ch Rockambo / mb Mambo jambo / mb Mama Inez / r MS Tabu / r ML JUAN BRUNO TARRAZA (cu) Caibarién, Las Villas, 10/6/1917 - México, D.F., 5/23/2001. He had a musical background in the family, and he played other instruments until he sat at the piano, and as a child he played at the Caibarién Yacht Club The trip to Havana occurred in 1935, he played first with the maestro Valdespí's orchestra, in 1937 he went to the Riverside orchestra and shortly afterwards he started working at the CMQ, where he worked with the Mexican singers who brought the Crusellas and company program, such as Tito Guizar, Juan Arvizu and even the temperamental Elvira Ríos, with whom he got along so well that they went on tour for Buenos Aires and Mexico, in 1942. -

Bigbang Mp3 Download

Bigbang mp3 download Continue Flash player flash player big bang - if you (instrumental cover of modern disco postdisco) mp3, 320 kbit, 320 kbit, sorry for using the old one. BIG BANG - IF YOU (3:56) BIGBANG - IF YOU (Chill Instrumental Cover) (4:35) BIGBANG - If you (Cello Cover) (3:53) suggi - if you (big blast cover) (4:25) BIGBANG - IF YOU (live) (4:23) D.SO x P.KEYS x J.CHEN - If you (live) (4) (4:23) D.SO x P.KEYS x J.CHEN - If You (Live) (YouBANG BIGCOVER) (3:53) Kiri KERY PARK (WL1) - BIGBANG 'IF YOU' (GETTY) rus) (4:23) - Bigbang - If you (4:24) BigBang (BIGBANG) - IF YOU -JP Ver.- (4:27) Micro lis - If you (BIG BANG) (4:24) I'm a fool, I stand like a fool, but I think I'm going to be boring again after a while because I'm just looking at the back of the story. Yes yes, I think if you're not too late, you can't go back if you're like me, if you can't go a little easier, you're going to do well when you're a bit like me. If you're not late, we won't be able to come back, if you're like me, we'll be fine when it rains a little easier, and on a rainy day like this, your shadow comes to mind, and we're reminded of our memories that we sneaked into a drawer, and you don't know why you weighed in with grief. -

AIR EMISSION PERMIT NO. 06100004-005 Major Amendment

AIR EMISSION PERMIT NO. 06100004-005 Major Amendment IS ISSUED TO Minnesota Power Division of ALLETE Inc. WPPI Energy MINNESOTA POWER INC. - BOSWELL ENERGY CENTER 1210 Northwest 3rd Street Cohasset, Itasca County, Minnesota 55721 The emission units, control equipment and emission stacks at the stationary source authorized in this permit amendment are as described in the Permit Applications Table. Upon the Authorization to Construct and Operate (40 CFR § 52.21) Effective Date, this permit amendment will supersede Air Emission Permit No. 06100004-004 and authorize the Permittee to operate and modify the stationary source at the address listed above unless otherwise noted in Table A. The Permittee must comply with all the conditions of the permit. Any changes or modifications to the stationary source must be performed in compliance with Minn. R. 7007.1150 to 7007.1500. Terms used in the permit are as defined in the state air pollution control rules unless the term is explicitly defined in the permit. Unless otherwise indicated, all the Minnesota rules cited as the origin of the permit terms are incorporated into the State Implementation Plan under 40 CFR § 52.1220, and as such are enforceable by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Administrator or citizens under the Clean Air Act. Permit Type: Federal; Part 70/Major for New Source Review Operating Permit Issue Date: 03/28/2007 Major Amendment Issue Date: July 16, 2010 Authorization to Construct and Operate (40 CFR § 52.21) Effective Date: August 19, 2010 Expiration Date: 03/28/2012– -

Gd&T Tolerance Stack up Analysis

Gd Continue For G-Dragon's eponymous EP, see Kwon Ji Yong. The merger is being considered for the merger of the South Korean singer, rapper and producer Pattern below (Korean name). See the templates for discussion to help reach consensus. It's a Korean name; Kwon's last name. G-DragonG-Dragon on Infinite Challenge Yeongdong Expressway Song Festival 2015BornKwon Ji-yong (1988-08-18) August 18, 1988 (age 32)Seoul, South KoreaOther namesGDOccupationRappersingersongwriterrecord producerentrepreneurfashion designerNet worthUS$40 million[1]Musical careerGenresHip hopK-popdance-popR&BtrapInstrumentsVocalsYears active1994– presentLabelsYGAssociated actsBig BangYG FamilyGD & TOPGD X TaeyangKorean nameHangul권지용Hanja權志⿓Revised RomanizationGwon Ji-yongMcCune–ReischauerKwŏn Chiyong Websiteygbigbang.com/gdragonSignature Kwon Ji-yong (Korean: 권지용; born August 18, 1988),[2] also known by his stage name G-Dragon, is a South Korean rapper, singer-songwriter, record producer, entrepreneur and fashion designer, dubbed as the 'King of K-Pop'. G-Dragon trained for six years, from the age of twelve, on the South Korean entertainment label YG Entertainment, before debuting in 2006 as the leader of the hip-hop boy band Big Bang, which became one of the best-selling boy bands in the world. His first solo album, Heartbreaker, and his title track of the same name, released in 2009, were commercially successful, becoming the top-selling album of the Korean soloist at the time and earning him album of the year at the Mnet Asian Music Awards 2009. G-Dragon collaborated with Big Bang Bandmate T.O.P to release the album GD and TOP in 2010. His first EP, One of a Kind (2012), received critical acclaim and three singles: One of a Kind, Crayon and That XX. -

Historic Preservation

5 HISTORIC PRESERVATION Shipyard aerial, 1945 3 6 | P ier 7 0 P referred M aster P lan Chapter 5: Historic PreserVation The Pier 70 Historic District showcases a wide range of archi- 3. Encourage adaptive reuse of the historic resources that add new tectural styles from the late 19th to the mid-20th centuries and life to Pier 70, consistent with Secretary Standards. includes a combination of master architect, “Cathedral of Industry” style complexes, landmark quality buildings, and more modest utili- 4. Apply design criteria for new infill development to ensure new tarian industrial structures. It is the oldest, largest and most intact construction meets Plan objectives and is sensitively designed, historic industrial complex in San Francisco. consistent with Secretary Standards. As a district, Pier 70 contains a rich collection of resources and 5. Prioritize the stabilization and rehabilitation of Very Significant provides a physical record expressing continuity with past trends in resources along 20th Street for public and private investment as industrial architecture and design. It is significant for its association early as possible. with pioneering technological developments in shipbuilding, labor relations, government, and private industry relationships, as well as 6. Promote an understanding of the site’s history, significance, and HISTORIC PRESERVATION for the production of significant wartime vessels. The district is also function through a program of coordinated interpretive exhibits significant because it includes important works of master architects. in public areas and open spaces and as part of new development 5 and historic rehabilitation improvements. Objectives 1. Recognize continuation of viable ship repair and drydock Historic Resources operations as an act of preserving Pier 70’s history, and give Pier 70 hosts a number of individual historic resources of varying priority to physical shipyard changes necessary to support the significance.