3. the Rotuman Experience with Reverse Migration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotuman Educational Resource

Fäeag Rotuam Rotuman Language Educational Resource THE LORD'S PRAYER Ro’ạit Ne ‘Os Gagaja, Jisu Karisto ‘Otomis Ö’fāat täe ‘e lạgi, ‘Ou asa la ȧf‘ȧk la ma’ma’, ‘Ou Pure'aga la leum, ‘Ou rere la sok, fak ma ‘e lạgi, la tape’ ma ‘e rȧn te’. ‘Äe la nāam se ‘ạmisa, ‘e terạnit 'e ‘i, ta ‘etemis tē la ‘ā la tạu mar ma ‘Äe la fạu‘ạkia te’ ne ‘otomis sara, la fak ma ne ‘ạmis tape’ ma rē vạhia se iris ne sar ‘e ‘ạmisag. ma ‘Äe se hoa’ ‘ạmis se faksara; ‘Äe la sại‘ạkia ‘ạmis ‘e raksa’a, ko pure'aga, ma ne’ne’i, ma kolori, mou ma ke se ‘äeag, se av se ‘es gata’ag ne tore ‘Emen Rotuman Language 2 Educational Resource TABLE OF CONTENTS ROGROG NE ĀV TĀ HISTORY 4 ROGROG NE ROTUMA 'E 'ON TẠŪSA – Our history 4 'ON FUẠG NE AS TA ROTUMA – Meaning behind Rotuma 5 HẠITOHIẠG NE FUẠG FAK PUER NE HANUA – Chiefly system 6 HATAG NE FĀMORI – Population 7 ROTU – Religion 8 AGA MA GARUE'E ROTUMA – Lifestyle on the island 8 MAK A’PUMUẠ’ẠKI(T) – A treasured song 9 FŪ’ÅK NE HANUA GEOGRAPHY 10 ROTUMA 'E JAJ(A) NE FITI – Rotuma on the map of Fiji 10 JAJ(A) NE ITU ’ HIFU – Map of the seven districts 11 FÄEAG ROTUẠM TA LANGUAGE 12 'OU ‘EA’EA NE FÄEGA – Pronunciation Guide 12-13 'ON JĪPEAR NE FÄEGA – Notes on Spelling 14 MAF NE PUKU – The Rotuman Alphabet 14 MAF NE FIKA – Numbers 15 FÄEAG ‘ES’ AO - Useful words 16-18 'OU FÄEAG’ÅK NE 'ÄE – Introductions 19 UT NE FAMORI A'MOU LA' SIN – Commonly Frequented Places 20 HUẠL NE FḀU TA – Months of the year 21 AG FAK ROTUMA CULTURE 22 KATO’ AGA - Traditional ceremonies 22-23 MAMASA - Welcome Visitors and returnees 24 GARUE NE SI'U - Artefacts 25 TĒFUI – Traditional garland 26-28 MAKA - Dance 29 TĒLA'Ā - Food 30 HANUJU - Storytelling 31-32 3 ROGROG NE ĀV TĀ HISTORY Legend has it that Rotuma’s first inhabitants Consequently, the two religious groups originated from Samoa led by Raho, a chief, competed against each other in the efforts to followed by the arrival of Tongan settlers. -

We Are Kai Tonga”

5. “We are Kai Tonga” The islands of Moala, Totoya and Matuku, collectively known as the Yasayasa Moala, lie between 100 and 130 kilometres south-east of Viti Levu and approximately the same distance south-west of Lakeba. While, during the nineteenth century, the three islands owed some allegiance to Bau, there existed also several family connections with Lakeba. The most prominent of the few practising Christians there was Donumailulu, or Donu who, after lotuing while living on Lakeba, brought the faith to Moala when he returned there in 1852.1 Because of his conversion, Donu was soon forced to leave the island’s principal village, Navucunimasi, now known as Naroi. He took refuge in the village of Vunuku where, with the aid of a Tongan teacher, he introduced Christianity.2 Donu’s home island and its two nearest neighbours were to be the scene of Ma`afu’s first military adventures, ostensibly undertaken in the cause of the lotu. Richard Lyth, still working on Lakeba, paid a pastoral visit to the Yasayasa Moala in October 1852. Despite the precarious state of Christianity on Moala itself, Lyth departed in optimistic mood, largely because of his confidence in Donu, “a very steady consistent man”.3 He observed that two young Moalan chiefs “who really ruled the land, remained determined haters of the truth”.4 On Matuku, which he also visited, all villages had accepted the lotu except the principal one, Dawaleka, to which Tui Nayau was vasu.5 The missionary’s qualified optimism was shattered in November when news reached Lakeba of an attack on Vunuku by the two chiefs opposed to the lotu. -

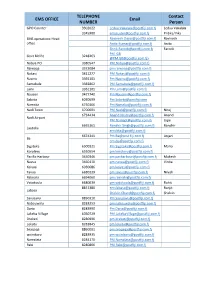

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Fara Way Rotuma

from Stories of the Southern Sea, by Lawrence Winkler Published as a Kindle book on December 26, 2013 Fara Way Rotuma “Their bodies were curiously marked with the figures of men, dogs, fishes and birds upon every part of them; so that every man was a moving landscape.” George Hamilton, Pandora’s surgeon, 1791 The whole scene was a moving landscape, directly under us, just over two hundred years after Captain Edwards had arrived on the HMS Pandora. He had been looking for the Bounty. We would find another. The pilot of our Britten-Norman banked off the huge cloud he had found over six hundred kilometers north of the rest of Fiji, and sliced down into it sideways, like he was cutting a grey soufflé. Nothing could have prepared us for the magnificence that opened up below, with the dispersal of the last gasping mists. A fringing reef, barely holding back the eternal explosions of rabid frothing foam and every blue in the reflected cosmos, encircled every green in nature. On the edge of both creations were the most spectacular beaches in the Southern Sea. Captain Edwards had called it Grenville Island. Two hundred years earlier, it was named Tuamoco by de Quiros, before he went on to establish his doomed New Jerusalem in Vanuatu. But that was less important for the moment. We had reestablished level flight, and were lining up on the dumbbell- shaped island’s only rectangular open space, a long undulating patch of grass, between the mountains and the ocean. Hardly more than a lawn bowling pitch anywhere else, here it was the airstrip, beside which a tiny remote paradise was waving all its arms. -

Fiji Meteorological Service Government of Republic of Fiji

FIJI METEOROLOGICAL SERVICE GOVERNMENT OF REPUBLIC OF FIJI MEDIA RELEASE No. 13 1pm, Wednesday, 16 December, 2020 SEVERE TC YASA INTENSIFIES FURTHER INTO A CATEGORY 5 SYSTEM AND SLOW MOVING TOWARDS FIJI Warnings A Tropical Cyclone Warning is now in force for Yasawa and Mamanuca Group, Viti Levu, Vanua Levu and nearby smaller islands and expected to be in force for the rest of the group later today. A Tropical Cyclone Alert remains in force for the rest Fiji A Strong Wind Warning remains in force for the rest of Fiji. A Storm Surge and Damaging Heavy Swell Warning is now in force for coastal waters of Rotuma, Yasawa and Mamanuca Group, Viti Levu, Vanua Levu and nearby smaller islands. A Heavy Rain Warning remains in force for the whole of Fiji. A Flash Flood Alert is now in force for all low lying areas and areas adjacent to small streams along Komave to Navua Town, Navua Town to Rewa, Rewa to Korovou and Korovou to Rakiraki in Vanua Levu and is also in force for all low lying areas and areas adjacent to small streams of Vanua Levu along Bua to Dreketi, Dreketi to Labasa and along Labasa to Udu Point. Situation Severe tropical cyclone Yasa has rapidly intensified and upgraded further into a category 5 system at 3am today. Severe TC Yasa was located near 14.6 south latitude and 174.1 east longitude or about 440km west-northwest of Yasawa-i-Rara, about 500km northwest of Nadi and about 395km southwest of Rotuma at midday today. The system is currently moving eastwards at about 6 knots or 11 kilometers per hour. -

Flood Hazard Modelling and Risk Assessment in the Nadi River Basin, Fiji, Using GIS and MCDA

CSIRO PUBLISHING The South Pacific Journal of Natural and Applied Sciences, 30, 33-43, 2012 www.publish.csiro.au/journals/spjnas 10.1071/SP12003 Flood hazard modelling and risk assessment in the Nadi River Basin, Fiji, using GIS and MCDA Jessy Paquette and John Lowry School of Geography, Earth Science and Environment, Faculty of Science, Technology and Environment, The University of the South Pacific, Private Mail Bag, Suva, Fiji. Abstract This paper presents a simple and affordable approach to flood hazard assessment in a region where primary data are scarce. Using a multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA) approach coupled with GIS layers for elevation, catchments, land-use, slope, distance from channel, and soil types, we model the spatial extent of flood hazard in the Nadi River basin in western Fiji. Based on the flood hazard model results we assess risk to flood hazards in the greater Nadi area. This is carried out using 2007 census data and building location data obtained from aerial photography. The flood model reveals that the highest hazard areas in Nadi are the Narewa, Sikituru and Yavusania villages followed by the Nadi central business district (Nadi CBD). Closer examination of the data suggests that the Nadi River is not the only flood vector in the area. Several poorly designed storm drains also present a hazard since they get clogged by rubbish and cannot properly evacuate runoff thus creating water build-up. We conclude that the MCDA approach provides a simple and effective means to model flood hazard using basic GIS data. This type of model can help decision makers focus their flood risk awareness efforts, and gives important insights to disaster management authorities. -

4.3 Fiji Port and Waterways Company Contact List Fiji Port and Waterways Company Contact List

4.3 Fiji Port and Waterways Company Contact List Fiji Port and Waterways Company Contact List Port Name Company Physical Address Website & Email Phone Number (office & Fa Description of Duties mobile) x N u m ber All Fiji Fiji Ports n/a http://www.portofsuva. +679 6662160 +6 Port Management Ports Corporation com 79 Limited 66 65 799 All Bollore 8-9 Freeston Road, Walu Bay, Chandima +679 3315044 +6 Transporter, shipping, storage: (Pacific Logistics Suva, Fiji Gunawardana, General 79 Island (Fiji) Ltd Manager. chandima. Shipping: MV Internatio gunawardana@bollor e. 33 nal Ports) com 15 Subritzky 120 MT, cargo capacity. MV, 055 Kusima 110 MT, cargo capacity MV, Mobile: +679 9994869 Kawai 115 MT, cargo capacity Ronald Dass, Manager Operations. Ronald [email protected] Mobile: +679 9905910 All (Fiji Fiji Ports n/a http://www.portofsuva. +679 6662160 +6 Port Management Ports) Corporation com 79 Limited 66 65 799 All / Suva Government Governments Wharf iliesa. Freight Superintendent: Mr. n Govt Only Shipping Shipping [email protected] Iliesa Raketekete /a Services Off Amra Street, Walu Bay, http://www. (GSS) Suva governmentshipping.gov. Tel: +679 3312246 fj Mobile: +6793314561 Port of Sea Road Fiji Seaboard Service pattersonship@connect. Sanjay Prasad n Shipping Schedule - Patterson Brothers S Suva Patterson (Patterson Brothers Seaboard com.fj /a eaboard Shipping co Brothers Shipping Co Ltd) Suite 182, + 679 3315644 Seaboard Epwoth House, Nina Street, Shipping co. Suva, Fiji. +6799221335 Port of Goundar Lot 22, Freeston Road, Walu goundarshipping@kidane Tel: + 679 3301060 n Shipping Schedule - Goundar Shipping Suva Shipping co. Bay, Suva. t.com.fj /a co Mobile: +6797775471 (Rakesh) +679 7775462 (Krishna) Vanua Wharf off Amra Street, Walu http://www. -

Researchspace@Auckland

http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz ResearchSpace@Auckland Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. To request permissions please use the Feedback form on our webpage. http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/feedback General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. CONNECTING IDENTITIES AND RELATIONSHIPS THROUGH INDIGENOUS EPISTEMOLOGY: THE SOLOMONI OF FIJI ESETA MATEIVITI-TULAVU A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Auckland Auckland, New Zealand 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................. vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................ -

Poverty Maps) in Republic of Fiji (2003-2009)

Report No.: 63842-FJ Republic of Fiji Public Disclosure Authorized Poverty Trends, Profiles and Small Area Estimation (Poverty Maps) in Republic of Fiji (2003-2009) September 15, 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective June 7, 2011) Currency Unit = Fijian Dollar USD 1.00 = FJ$ 1.76991 FJ$ 1 = USD 0.565000 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADePT Software Platform for Automated Economic Analysis AusAID Australian Agency for International Development DSW Department of Social Welfare GIC Growth Incidence Curve FAO Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations FAP Family Assistance Program FIBOS Fiji Island Bureau of Statistics HIES Household Income and Expenditure Surveys pAE Per Adult Expenditure Regional Vice President: James W. Adams Country Director: Ferid Belhaj Sector Director: Emmanuel Jimenez Sector Manager: Xiaoqing Yu Task Team Leader: Oleksiy Ivaschenko Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... v Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... vii 1 Background ........................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Poverty methodology........................................................................................................................... -

Indigenous Itaukei Worldview Prepared by Dr

Indigenous iTaukei Worldview Prepared by Dr. Tarisi Vunidilo Illustration by Cecelia Faumuina Author Dr Tarisi Vunidilo Tarisi is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo, where she teaches courses on Indigenous museology and heritage management. Her current area of research is museology, repatriation and Indigenous knowledge and language revitalization. Tarisi Vunidilo is originally from Fiji. Her father, Navitalai Sorovi and mother, Mereseini Sorovi are both from the island of Kadavu, Southern Fiji. Tarisi was born and educated in Suva. Front image caption & credit Name: Drua Description: This is a model of a Fijian drua, a double hulled sailing canoe. The Fijian drua was the largest and finest ocean-going vessel which could range up to 100 feet in length. They were made by highly skilled hereditary canoe builders and other specialist’s makers for the woven sail, coconut fibre sennit rope and paddles. Credit: Commissioned and made by Alex Kennedy 2002, collection of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, FE011790. Link: https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/648912 Page | 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 SECTION 2: PREHISTORY OF FIJI .............................................................................................................. 5 SECTION 3: ITAUKEI SOCIAL STRUCTURE ............................................................................................... -

Priorities of the People: Hardship in the Fiji Islands

Priorities of the People HARDSHIP IN THE FIJI ISLANDS September 2003 Asian Development Bank © Asian Development Bank 2003 All rights reserved This publication was prepared by consultants for the Asian Development Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in it do not necessarily repre- sent the views of ADB or those of its member governments. ADB does not guar- antee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility whatsoever for any consequences of their use. Asian Development Bank P.O. Box 789, 0980 Manila, Philippines Website: www.adb.org Contents Introduction 1 Is Hardship Really a Problem in the Fiji Islands? 3 What is Hardship? 4 Who is Facing Hardship? 6 What Causes Hardship? 7 What Can be Done? 13 © Asian Development Bank 2003 All rights reserved This publication was prepared by consultants for the Asian Development Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in it do not necessarily repre- sent the views of ADB or those of its member governments. ADB does not guar- antee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility whatsoever for any consequences of their use. Asian Development Bank P.O. Box 789, 0980 Manila, Philippines Website: www.adb.org Contents Introduction 1 Is Hardship Really a Problem in the Fiji Islands? 3 What is Hardship? 4 Who is Facing Hardship? 6 What Causes Hardship? 7 What Can be Done? 13 Introduction iji has commonly been viewed as a society with deep inequalities, but little absolute poverty. But many F people now believe that poverty—in the form of destitu- tion, homelessness, and hunger—exists in Fiji. -

Rotuman Identity in the Electronic Age

ALAN HOWARD and JAN RENSEL Rotuman identity in the Electronic Age For some groups cultural identity comes easy; at least it's relatively unprob- lematic. As Fredrik Barth (1969) pointed out many years ago, where bounda ries between groups are fixed and rigid, theories of group distinctiveness thrive. Boundaries can be set according to a wide range of physical, social, or cultural characteristics ranging from skin colour, religious affiliation or beliefs, occupations, to what people eat, and so on. Social hierarchy also can play a determining role, especially when a dominating group's social theory divides people into categories on the basis of geographical origins, blood lines, or some other defining characteristic, restricting their identity options. In the United States, for example, the historical category of 'negro' allowed little room for choice; any US citizen with an African ancestor was assigned to the category regardless of personal preference. Although in Polynesia social boundaries have traditionally been porous, cultural politics has transformed categories like 'New Zealand Maori' and 'Hawaiian' into strong identities, despite more personal choice and somewhat flexible boundaries. In these cases, where indigenous people were subjugated by European or American colonists, a long period of historically muted iden tity gave way in the last decades of the twentieth century to a Polynesian cul tural renaissance that has been accompanied by a hardening of social catego ries and a dramatic strengthening of Maori and Hawaiian identities. Samoans also have a relatively strong sense of cultural identity, but for a different reason. In their case, identity is reinforced by a commitment to fa'asamoa, the Samoan way of life.