The Walkabout in an Alternative High School: Narrative As a Social Practice for Reflection on and Analysis of Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differences in Energy and Nutritional Content of Menu Items Served By

RESEARCH ARTICLE Differences in energy and nutritional content of menu items served by popular UK chain restaurants with versus without voluntary menu labelling: A cross-sectional study ☯ ☯ Dolly R. Z. TheisID *, Jean AdamsID Centre for Diet and Activity Research, MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United a1111111111 Kingdom a1111111111 ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Background OPEN ACCESS Poor diet is a leading driver of obesity and morbidity. One possible contributor is increased Citation: Theis DRZ, Adams J (2019) Differences consumption of foods from out of home establishments, which tend to be high in energy den- in energy and nutritional content of menu items sity and portion size. A number of out of home establishments voluntarily provide consumers served by popular UK chain restaurants with with nutritional information through menu labelling. The aim of this study was to determine versus without voluntary menu labelling: A cross- whether there are differences in the energy and nutritional content of menu items served by sectional study. PLoS ONE 14(10): e0222773. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222773 popular UK restaurants with versus without voluntary menu labelling. Editor: Zhifeng Gao, University of Florida, UNITED STATES Methods and findings Received: February 8, 2019 We identified the 100 most popular UK restaurant chains by sales and searched their web- sites for energy and nutritional information on items served in March-April 2018. We estab- Accepted: September 6, 2019 lished whether or not restaurants provided voluntary menu labelling by telephoning head Published: October 16, 2019 offices, visiting outlets and sourcing up-to-date copies of menus. -

ENGLISH 2810: Television As Literature (V

ENGLISH 2810: Television as Literature (v. 1.0) 9:00 – 10:15 T/Th | EH 229 Dr. Scott Rogers | [email protected] | EH 448 http://faculty.weber.edu/srogers The Course The average American watches about 5 hours of television a day. We are told that this is bad. We are told that television is bad for us, that it is bad for our families, and that it is wasting our time. But not all television is that way. Some television shows have what we might call “literary pretensions.” Shows such as Twin Peaks, Homicide: Life on the Street, The Wire, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Firefly, Veronica Mars, Battlestar Galactica, and LOST have been both critically acclaimed and the subject of much academic study. In this course, we shall examine a select few of these shows, watching complete seasons as if they were self-contained literary texts. In other words, in this course, you will watch TV and get credit for it. You will also learn to view television in an active and critical fashion, paying attention to the standard literary techniques (e.g. character, theme, symbol, plot) as well as televisual issues such as lighting, music, and camerawork. Texts Students will be expected to own, or have access to, the following: Firefly ($18 on amazon.com; free on hulu.com) and Serenity ($4 used on amazon.com) LOST season one ($25 on amazon.com; free on hulu.com or abc.com) Battlestar Galactica season one ($30 on amazon.com) It is in your best interest to buy or borrow these, if only to make it easier for you to go back and re-watch episodes for your assignments. -

First Class Wording

YOUR IMPORTANT INFORMATION ENQUIRIES 01424 223964 IF YOU NEED EMERGENCY MEDICAL ASSISTANCE ABROAD OR NEED TO CUT SHORT YOUR TRIP: contact Emergency Assistance Facilities 24 hour emergency advice line on: +44 (0) 203 829 6745 FOR NON-EMERGENCIES ABROAD: +44 (0) 203 829 6761 IF YOU NEED A CLAIM FORM: you can download the relevant form: www.travel-claims.net or contact Travel Claims Facilities on: + 44 (0) 203 829 6761 IF YOU NEED LEGAL ADVICE: contact Slater & Gordon LLP on: +44 (0) 161 228 3851 Go Walkabout First Class FOR GADGET CLAIMS PLEASE CONTACT SUPERCOVER INSURANCE LTD: +44 (0) 203 794 9334 Master policy number RTYGW40009-08 A, B & C 9am-6pm Monday to Friday This insurance policy wording is a copy of the master policy wordings Or by emailing [email protected] and is subject to the same terms, conditions and exclusions. IF YOU NEED AN END SUPPLIER FAILURE CLAIM FORM CONTACT IPP CLAIMS OFFICE ON +44 (0) 208 776 3752 Go Walkabout Travel Insurance is arranged by & Underwritten by Travel Insurance Facilities & Insured by Union Reiseversicherung AG, UK. Travel Insurance Facilities are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Union Reiseversicherung This policy is for residents of the United Kingdom, AG are authorised by BaFin and subject to limited regulation Channel Islands or British Forces Posted Overseas only by the Financial Conduct Authority. For policies issued from 11/05/2017 to 13/02/2018 with travel before 13/02/2019 Page Contents Our pledge to you Page 1 2 Important contact numbers It is our aim to give a high standard of service and to meet any claims covered by these policies honestly, fairly and promptly. -

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space With

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space with Flashbacks and Flash-forwards in the Series "Lost" Promotor: Auteur: Prof. Dr. S. Slembrouck Olga Berendeeva Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde Afstudeerrichting: Master Engels Academiejaar 2008-2009 2e examenperiode For My Parents Who are so far But always so close to me Мои родителям, Которые так далеко, Но всегда рядом ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank Professor Dr. Stefaan Slembrouck for his interest in my work. I am grateful for all the encouragement, help and ideas he gave me throughout the writing. He was the one who helped me to figure out the subject of my work which I am especially thankful for as it has been such a pleasure working on it! Secondly, I want to thank my boyfriend Patrick who shared enthusiasm for my subject, inspired me, and always encouraged me to keep up even when my mood was down. Also my friend Sarah who gave me a feedback on my thesis was a very big help and I am grateful. A special thank you goes to my parents who always believed in me and supported me. Thanks to all the teachers and professors who provided me with the necessary baggage of knowledge which I will now proudly carry through life. iii Foreword In my previous research paper I wrote about film discourse, thus, this time I wanted to continue with it but have something new, some kind of challenge which would interest me. After a conversation with my thesis guide, Professor Slembrouck, we decided to stick on to film discourse but to expand it. -

Copyrighted Material

PART ON E F IS FOR FORTUNE COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL CCH001.inddH001.indd 7 99/18/10/18/10 77:13:28:13:28 AAMM CCH001.inddH001.indd 8 99/18/10/18/10 77:13:28:13:28 AAMM LOST IN LOST ’ S TIMES Richard Davies Lost and Losties have a pretty bad reputation: they seem to get too much fun out of telling and talking about stories that everyone else fi nds just irritating. Even the Onion treats us like a bunch of fanatics. Is this fair? I want to argue that it isn ’ t. Even if there are serious problems with some of the plot devices that Lost makes use of, these needn ’ t spoil the enjoyment of anyone who fi nds the series fascinating. Losing the Plot After airing only a few episodes of the third season of Lost in late 2007, the Italian TV channel Rai Due canceled the show. Apparently, ratings were falling because viewers were having diffi culty following the plot. Rai Due eventually resumed broadcasting, but only after airing The Lost Survivor Guide , which recounts the key moments of the fi rst two seasons and gives a bit of background on the making of the series. Even though I was an enthusiastic Lostie from the start, I was grateful for the Guide , if only because it reassured me 9 CCH001.inddH001.indd 9 99/18/10/18/10 77:13:28:13:28 AAMM 10 RICHARD DAVIES that I wasn’ t the only one having trouble keeping track of who was who and who had done what. -

131 West Nile Street Glasgow G1

house everything at your doorstep empire 131 WEST NILE STREET GLASGOW G1 2RX empirehouse 131 WEST NILE STREET GLASGOW G1 2RX leisure specification Glasgow Royal Concert Hall, Cineworld and Situated at the corner of West Nile Street Street Bus Station and numerous bus the Theatre Royal and Sauchiehall Street, Empire House is links, all just a stone’s throw away. There offer an abundance of • Modern open plan offices entertainmant choice one of the most “staff friendly” locations are on street and multi storey parking throughtout the year, in Glasgow city centre with fantastic facilities coveniently nearby. and all lie within close • New contemporary entrance hall shops, restaurants and leisure amenities proximity. on its doorstep. After work, the surrounding restaurants, • Office suites refurbished prior to entry bars, hotels, multi screen cinema, Furthermore, getting here could not concert hall and theatres provide eat + drink • Full time commissionaire be easier with Queen Street Station, staff with a vast choice of leisure and Buchanan Street Subway and Buchanan entertainment opportunities. From fast food to fine dining, • DDA compliant from coffee to cocktails, it’s all literally on the doorstep with Starbucks, Pret A Manger, • On site secure car parking KFC, La Bonne Auberge, Walkabout and many more • Cycle storage, showering and lockers nearby. • Security Door Entry System shopping • 24 Hour access Everyday essentials to little to let • Gas Central Heating luxuries, Empire House is Superb modern perfectly situated to take full advantge of Glasgow’s • Perimeter Trunking office suites excellent shopping provision available in a with Buchanan Galleries, • Comfort Cooled Suites Available Buchanan Quarter and variety of sizes. -

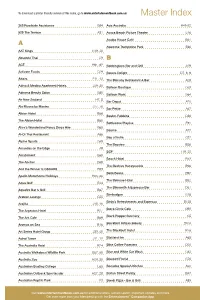

Master Index

To download a printer friendly version of this index, go to www.entertainmentbook.com.au Master Index 365 Roadside Assistance G84 Avis Australia H49-52 529 The Terrace A31 Avoca Beach Picture Theatre E46 Awaba House Café B61 A Awezone Trampoline Park E66 AAT Kings H19, 20 Absolute Thai C9 B ACE H61, 62 Babbingtons Bar and Grill A29 Activate Foods G29 Bakers Delight D7, 8, 9 Adairs F11, 12 The Balcony Restaurant & Bar A28 Adina & Medina Apartment Hotels J29, 30 Balloon Boutique G63 Adnama Beauty Salon G50 Balloon Worx G64 Air New Zealand H7, 8 Bar Depot A20 Ala Moana by Mantra J77, 78 Bar Petite A67 Albion Hotel B66 Baskin-Robbins D36 The Albion Hotel B60 Battlezone Playlive E91 Alice’s Wonderland Fancy Dress Hire G65 Baume A77 Al-Oi Thai Restaurant A66 Bay of India C37 Alpine Sports G69 The Bayview B56 Amandas on the Edge A9 BCF F19, 20 Amazement E69 Beach Hotel B13 The Anchor B68 The Beehive Honeysuckle B96 And the Winner Is OSCARS B53 Bella Beans B97 Apollo Motorhome Holidays H65, 66 The Belmore Hotel B52 Aqua Golf E24 The Bikesmith & Espresso Bar D61 Aqua re Bar & Grill B67 Bimbadgen G18 Arabian Lounge C25 Birdy’s Refreshments and Espresso B125 Arajilla J15, 16 Black Circle Cafe B95 The Argenton Hotel B27 Black Pepper Butchery G5 The Ark Cafe B69 Aromas on Sea B16 Blackbird Artisan Bakery B104 Art Series Hotel Group J39, 40 The Blackbutt Hotel B76 Astral Tower J11, 12 Blaxland Inn A65 The Australia Hotel B24 Bliss Coffee Roasters D66 Australia Walkabout Wildlife Park E87, 88 Blue and White Car Wash G82 Australia Zoo H29, 30 Bluebird Florist G76 Australian Boating College E65 Bocados Spanish Kitchen A50 Australian Outback Spectacular H27, 28 Bolton Street Pantry B47 Australian Reptile Park E3 Bondi Pizza - Bar & Grill A85 Visit www.entertainmentbook.com.au for additional offers, suburb search, important updates and more. -

Board Walkabout - Thursday 31St May 2018, 08:30 – 09:45

Board Walkabout - Thursday 31st May 2018, 08:30 – 09:45 Meet in the Hyde Park Room at 08:30 At the time of your visit the wards and departments will be extremely busy. This is one of the busiest times for areas with morning ward rounds, medication and assistance with patient care being completed. Please ensure that your team is in the Hyde Park room for 09:45 to provide verbal feedback on your areas visited. Please nominate one individual to provide a summary of the findings who will be given 3 minutes to complete this. During your visit to areas this is an opportunity to meet with staff and understand the breadth of services that are provided. You are encouraged to discuss with staff the services they provide and challenges they may face. In addition to this we would ask that you continue to observe environmental cleanliness and infection control principles and therefore the following points may assist you in this process. 1. Are staff bare below the elbows in clinical areas and adhering to principles of hand washing? 2. Is the ward/department clutter free? 3. What impression are you given on entering? 4. Is the ward calm and organised? Is the ward odor free? 5. Are signs and notice boards clear and well displayed? 6. Is any unused equipment clean and labeled as clean and ready for use? 7. Are resus trollies, ledges etc free from dust? 8. Are there any outstanding urgent estates or maintenance issues? 9. What do staff enjoy most about working at St Georges Hospital? 10. -

Willow-Lodge-Brochure.Pdf

at Watford Riverwell A true breath of fresh air Watford Riverwell is a joint venture between Watford Borough Council and the construction and property company Kier. The regeneration project will be delivering homes, shops, a care community and other upgrades to the area near Watford General Hospital. As part of this development, Watford Community Housing will be helping to deliver and manage 29 homes for affordable rent and shared ownership. Williow Lodge, in the Woodlands section of Watford Riverwell, will provide 9 one-bed homes and 14 two-bed homes for shared ownership, as well as 6 two-bed apartments for affordable rent. 1 Lifestyle Shop Dine Meet Relax Watford is home to a vast array of shops, A great selection of eateries on its If you like to visit the theatre, you will be Home to the Green Flag award-winning including the recently extended Intu doorstep with a plethora of well-known spoilt for choice as you have both The Cassiobury Park where you can enjoy over shopping centre in the town centre which chains including Wagamama, Yo! Sushi, Watford Palace and Pump House theatres 190 acres of parkland housing the Cha houses retailers such as Debenhams, TGI Fridays and Zizzi to name a few. Or in the town centre. You also have the Café, children’s playground, outdoor gym, John Lewis, Apple Store and Hugo if you are after a caffeine fix you can take Watford Colosseum, which houses a miniature railway and paddling pools. Boss. Outside of the town centre is the your pick from Starbucks, Costa Coffee, variety of events from comedy, live music Waterfields Retail Park, where you can Pret A Manger and and dance. -

Go Walkabout First Class Key Facts YOUR IMPORTANT INFORMATION

YOUR IMPORTANT INFORMATION ENQUIRIES 01424 223964 IF YOU NEED EMERGENCY MEDICAL ASSISTANCE ABROAD OR NEED TO CUT SHORT YOUR TRIP: contact Emergency Assistance Facilities 24 hour emergency advice line on: +44 (0) 203 829 6745 FOR NON-EMERGENCIES ABROAD: +44 (0) 203 829 6761 IF YOU NEED A CLAIM FORM: you can download the relevant form: www.travel-claims.net or contact Travel Claims Facilities on: + 44 (0) 203 829 6761 IF YOU NEED LEGAL ADVICE: contact Slater & Gordon LLP on: Go Walkabout First Class +44 (0) 161 228 3851 FOR GADGET CLAIMS PLEASE CONTACT Key Facts SUPERCOVER INSURANCE LTD: +44 (0) 203 794 9334 Master policy number RTYGW40009-08 A, B & C 9am-6pm Monday to Friday This insurance policy wording is a copy of the master policy wordings Or by emailing [email protected] and is subject to the same terms, conditions and exclusions. IF YOU NEED AN END SUPPLIER FAILURE CLAIM FORM CONTACT IPP CLAIMS OFFICE ON +44 (0) 208 776 3752 Go Walkabout Travel Insurance is arranged by & Underwritten by Travel Insurance Facilities & Insured by Union Reiseversicherung AG, UK. Travel Insurance Facilities are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Union Reiseversicherung This policy is for residents of the United Kingdom, AG are authorised by BaFin and subject to limited regulation Channel Islands or British Forces Posted Overseas only by the Financial Conduct Authority. For policies issued from 11/05/2017 to 13/02/2018 with travel before 13/02/2019 Our pledge to you It is our aim to give a high standard of service and to meet any claims covered by these policies honestly, fairly and promptly. -

Report Name: Food Service - Hotel Restaurant Institutional

Required Report: Required - Public Distribution Date: September 28,2020 Report Number: UK2020-0028 Report Name: Food Service - Hotel Restaurant Institutional Country: United Kingdom Post: London Report Category: Food Service - Hotel Restaurant Institutional Prepared By: Julie Vasquez-Nicholson Approved By: Cynthia Guven Report Highlights: This report covers an overview of the UK food service market. THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Executive Summary The UK, a leading trading power and financial center, is the third largest economy in Europe. Agriculture is Independent stores continue to face strong competition intensive, highly mechanized, and efficient by European from modern grocery retailers. Online food sales are standards but, represents less than one percent of the showing tremendous growth, with the sector being valued Gross Domestic Product (GDP). While UK agriculture at $15.2 billion (£12.7 billion) in 2019. UK consumers are produces about 60 percent of the country’s food needs willing to try foods from other countries but expect with less than two percent of the labor force, the UK is quality products at a competitive price. heavily reliant on imports to meet the varied demands of the UK consumer who expects year-round availability of Quick Facts CY 2019 all food products. The UK is very receptive to goods and Imports of Consumer-Oriented Products -$49.0 billion services from the United States. With its $2.91 trillion GDP in 2019, the UK is the United States’ largest List of Top 10 Consumer-Oriented Growth Products in European market and fifth largest in the world for all UK goods. -

Anabat Walkabout Bat Detector

Anabat Walkabout Bat Detector User Manual Titley Scientific Version 1.6 Notice for Customers in the U.S.A Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Radio Frequency Interference Statement This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the limits for a Class B digital device, pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC rules. These limits are designed to provide reasonable protection against harmful interference in a residential installation. This equipment generates, uses, and can radiate radio frequency energy and, if not installed and used in accordance with the instructions, may cause harmful interference to radio communications. However, there is no guarantee that interference will not occur in a particular installation. If this equipment does cause harmful interference to radio or television reception, which can be determined by turning the equipment off and on, the user is encouraged to try to correct the interference by one or more of the following measures: • Reorient or relocate the receiving antenna. • Increase the separation between the equipment and receiver. • Connect the equipment into an outlet on a circuit different from that to which the receiver is connected. • Consult the dealer or an experienced radio/television technician for help. This device complies with Part 15 of the FCC Rules. Operation is subject to the following two conditions: (1) This device may not cause harmful interference, and (2) this device must accept any interference received, including interference that may cause undesired operation. CAUTION Modifications Changes or modifications not expressly approved by Titley Scientific could void the user's authority to operate the equipment. Interface Cables Use the interface cables sold or provided by Titley Scientific for your equipment.