S F COMMENTARY 23 DISCUSSED in ISSUE Zl7--.S .;F-.-.-Xomivlentftr-Y 23 CHECKLIST —------I;------:.4L £ '

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

To Sunday 31St August 2003

The World Science Fiction Society Minutes of the Business Meeting at Torcon 3 th Friday 29 to Sunday 31st August 2003 Introduction………………………………………………………………….… 3 Preliminary Business Meeting, Friday……………………………………… 4 Main Business Meeting, Saturday…………………………………………… 11 Main Business Meeting, Sunday……………………………………………… 16 Preliminary Business Meeting Agenda, Friday………………………………. 21 Report of the WSFS Nitpicking and Flyspecking Committee 27 FOLLE Report 33 LA con III Financial Report 48 LoneStarCon II Financial Report 50 BucConeer Financial Report 51 Chicon 2000 Financial Report 52 The Millennium Philcon Financial Report 53 ConJosé Financial Report 54 Torcon 3 Financial Report 59 Noreascon 4 Financial Report 62 Interaction Financial Report 63 WSFS Business Meeting Procedures 65 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Saturday…………………………………...... 69 Report of the Mark Protection Committee 73 ConAdian Financial Report 77 Aussiecon Three Financial Report 78 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Sunday………………………….................... 79 Time Travel Worldcon Report………………………………………………… 81 Response to the Time Travel Worldcon Report, from the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention…………………………… 82 WSFS Constitution, with amendments ratified at Torcon 3……...……………. 83 Standing Rules ……………………………………………………………….. 96 Proposed Agenda for Noreascon 4, including Business Passed On from Torcon 3…….……………………………………… 100 Site Selection Report………………………………………………………… 106 Attendance List ………………………………………………………………. 109 Resolutions and Rulings of Continuing Effect………………………………… 111 Mark Protection Committee Members………………………………………… 121 Introduction All three meetings were held in the Ontario Room of the Fairmont Royal York Hotel. The head table officers were: Chair: Kevin Standlee Deputy Chair / P.O: Donald Eastlake III Secretary: Pat McMurray Timekeeper: Clint Budd Tech Support: William J Keaton, Glenn Glazer [Secretary: The debates in these minutes are not word for word accurate, but every attempt has been made to represent the sense of the arguments made. -

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

The Tarzan Series of Edgar Rice Burroughs

I The Tarzan Series of Edgar Rice Burroughs: Lost Races and Racism in American Popular Culture James R. Nesteby Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy August 1978 Approved: © 1978 JAMES RONALD NESTEBY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ¡ ¡ in Abstract The Tarzan series of Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875-1950), beginning with the All-Story serialization in 1912 of Tarzan of the Apes (1914 book), reveals deepseated racism in the popular imagination of early twentieth-century American culture. The fictional fantasies of lost races like that ruled by La of Opar (or Atlantis) are interwoven with the realities of racism, particularly toward Afro-Americans and black Africans. In analyzing popular culture, Stith Thompson's Motif-Index of Folk-Literature (1932) and John G. Cawelti's Adventure, Mystery, and Romance (1976) are utilized for their indexing and formula concepts. The groundwork for examining explanations of American culture which occur in Burroughs' science fantasies about Tarzan is provided by Ray R. Browne, publisher of The Journal of Popular Culture and The Journal of American Culture, and by Gene Wise, author of American Historical Explanations (1973). The lost race tradition and its relationship to racism in American popular fiction is explored through the inner earth motif popularized by John Cleves Symmes' Symzonla: A Voyage of Discovery (1820) and Edgar Allan Poe's The narrative of A. Gordon Pym (1838); Burroughs frequently uses the motif in his perennially popular romances of adventure which have made Tarzan of the Apes (Lord Greystoke) an ubiquitous feature of American culture. -

The Apocalyptic Book List

The Apocalyptic Book List Presented by: The Post Apocalyptic Forge Compiled by: Paul Williams ([email protected]) As with other lists compiled by me, this list contains material that is not strictly apocalyptic or post apocalyptic, but that may contain elements that have that fresh roasted apocalyptic feel. Because I have not read every single title here and have relied on other peoples input, you may on occasion find a title that is not appropriate for the intended genre....please do let me know and I will remove it, just as if you find a title that needs to be added...that is appreciated as well. At the end of the main book list you will find lists for select series of books. Title Author 8.4 Peter Hernon 905 Tom Pane 2011, The Evacuation of Planet Earth G. Cope Schellhorn 2084: The Year of the Liberal David L. Hale 3000 Ad : A New Beginning Jon Fleetwood '48 James Herbert Abyss, The Jere Cunningham Acts of God James BeauSeigneur Adulthood Rites Octavia Butler Adulthood Rites, Vol. 2 Octavia E. Butler Aestival Tide Elizabeth Hand Afrikorps Bill Dolan After Doomsday Poul Anderson After the Blue Russel C. Like After the Bomb Gloria D. Miklowitz After the Dark Max Allan Collins After the Flames Elizabeth Mitchell After the Flood P. C. Jersild After the Plague Jean Ure After the Rain John Bowen After the Zap Michael Armstrong After Things Fell Apart Ron Goulart After Worlds Collide Edwin Balmer, Philip Wylie Aftermath Charles Sheffield Aftermath K. A. Applegate Aftermath John Russell Fearn Aftermath LeVar Burton Aftermath, The Samuel Florman Aftershock Charles Scarborough Afterwar Janet Morris Against a Dark Background Iain M. -

No Truce with Kings” Karen Anderson on Poul Anderson’S Hall of Fame Award

Liberty, Art, & Culture Vol. 29, No. 1 Fall 2010 Inspiration for Poul Anderson’s “No Truce with Kings” Karen Anderson on Poul Anderson’s Hall of Fame Award I wish to thank the members of the Libertarian Future loses itself in a desert sink. We knew the farmland and pastures Society for honoring Poul’s work yet again. He particularly of the Central Valley, watered in those days only by the San valued these awards; the three plaques for stories, and that Joaquin river that meets the Sacramento in the great inland for the Lifetime Achievement Award, were displayed above delta, and the cave-riddled Pinnacles under Fremont Peak in the desk where he worked. the center of the state. I made several false starts on this acceptance, but finally We’d seen missions, presidios, and barracks from San Diego concluded it would be best just to tell you a little about the de Alcalá up the Camino Real by San Juan Bautista and San man who wrote it—where he lived, what he’d done lately, Francisco de Asís, to San Francisco Solano in Sonoma, north what he did on his vacations. of the Bay; and further north on the coast we’d visited the Poul was a fan before he was a pro, and we met at the Russian fort with its Orthodox church; Spain and Russia both 1952 Worldcon. He’d been born in Pennsylvania, spent his wanted San Francisco Bay, even before the gold was found in boyhood in Texas, and after periods in Denmark and outside 1849. -

Starfarer's Handbook

Requires the use of the Dungeons & Dragons® Player's Handbook starfarer s handbook credits ORIGINAL CREATION PRINTING Greg Benage Quebecor Printing, Inc. Printed in Canada WRITING AND DESIGN PLAYTESTING AND FEEDBACK Greg Benage and Matt Forbeck Chad Boyer, Andrew Christian, Mike Coleman, INTERIOR ILLUSTRATIONS Jacob Driscoll, Claus Emmer, Greg Frantsen, Tod Gelle, Jason Kemp, Tracy McCormick, Ragin Andy Brase, Darren Calvert, Mitch Cotie, Jesper Miller, Brian Schomburg, Erik Terrell, Chris White, Ejsing, David Griffith, Dave Lynch, Klaus Brian Wood, and everyone on the Dragonstar mail- Scherwinksi, Brian Schomburg, Simone Bianchi, ing list Jean-Pierre Targete, Kieran Yanner GRAPHIC DESIGN GREG’S DEDICATION Brian Schomburg To my moms, who gave me the world and taught COVER DESIGN me to dream of the stars. Brian Schomburg MATT’S DEDICATION EDITING AND LAYOUT To George Lucas and Dave Arneson & E. Gary Greg Benage Gygax for firing my generation's imagination. ART DIRECTION Brian Wood ‘d20 System’ and the d20 System logo are PUBLISHER Trademarks owned by Wizards of the Coast and are used with permission. Christian T. Petersen Dungeons & Dragons® and Wizards of the Coast® are Registered Trademarks of Wizards of the Coast, and are used with Permission. FANTASY FLIGHT GAMES 1975 W. County Rd. B2 #1 Dragonstar © 2001, Fantasy Flight, Inc. Roseville, MN 55113 All rights reserved. 651.639.1905 www.fantasyflightgames.com contents CHAPTER 1: WELCOME TO DRAGONSTAR . .4 CHAPTER 2: RACES . .17 CHAPTER 3: CLASSES . .35 CHAPTER 4: SKILLS . .70 CHAPTER 5: FEATS . .85 CHAPTER 6: EQUIPMENT . .91 CHAPTER 7: COMBAT . .124 CHAPTER 8: MAGIC . .136 CHAPTER 9: VEHICLES . .150 Introduction The Open Game License The Dragonstar Starfarer’s Handbook is published 3 Fantasy Flight Games is pleased to present under the terms of the Open Game License and the d20 Dragonstar, a unique space fantasy campaign setting System Trademark License. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction

Andrew May Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction Editorial Board Mark Alpert Philip Ball Gregory Benford Michael Brotherton Victor Callaghan Amnon H Eden Nick Kanas Geoffrey Landis Rudi Rucker Dirk Schulze-Makuch Ru€diger Vaas Ulrich Walter Stephen Webb Science and Fiction – A Springer Series This collection of entertaining and thought-provoking books will appeal equally to science buffs, scientists and science-fiction fans. It was born out of the recognition that scientific discovery and the creation of plausible fictional scenarios are often two sides of the same coin. Each relies on an understanding of the way the world works, coupled with the imaginative ability to invent new or alternative explanations—and even other worlds. Authored by practicing scientists as well as writers of hard science fiction, these books explore and exploit the borderlands between accepted science and its fictional counterpart. Uncovering mutual influences, promoting fruitful interaction, narrating and analyzing fictional scenarios, together they serve as a reaction vessel for inspired new ideas in science, technology, and beyond. Whether fiction, fact, or forever undecidable: the Springer Series “Science and Fiction” intends to go where no one has gone before! Its largely non-technical books take several different approaches. Journey with their authors as they • Indulge in science speculation—describing intriguing, plausible yet unproven ideas; • Exploit science fiction for educational purposes and as a means of promoting critical thinking; • Explore the interplay of science and science fiction—throughout the history of the genre and looking ahead; • Delve into related topics including, but not limited to: science as a creative process, the limits of science, interplay of literature and knowledge; • Tell fictional short stories built around well-defined scientific ideas, with a supplement summarizing the science underlying the plot. -

By Poul Anderson Change Without Notice Before, During, Or After the Convention

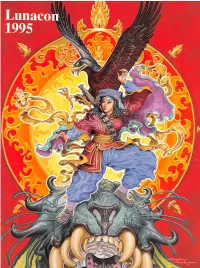

NEW EMPIRES Expansion Set!!! i. Four All New Empires! .A 0 Entity (ultra rare) cards found only in the first print run! r Basic Deck C - CGE1120450 nonrandom cards) $6.95 ea. 127display Expansion Packs - CGE5110 (12 random cards) $2.45 ea. 36/Display ! GALACTIC EMPIRES™ Primary Edition: The 430 card major release! First print run going, going... will beholding Fantastic Graphics and illustrations! s half hour demonstrations games of Eight different empires! Plus 9 Entity (ultra rare) cards found only in the first print run! Galactic Empires in the gaming section. The Basic Deck A & B - CGE1110 (55 cards, 50 nonrandom) demonstrations of Galactic Empires will be $8.95ea. 12/display hosted by designers C. Henry Schulte and Expansion Packs - CGE4110 (12 random) $2.45 ea. 36/Display Richard J. Rausch. Every person who partici Limited Edition Prints (500 signed & numbered) Coming Soon! pates in the demonstration games will receive CLP0001 - ‘Assault on a Clydon Bridge’ (this illustration 20x24) $39.95 Illustration © 1995 Douglas Chaffee. an ultra-rare ‘entity’ card. Call Companion Games for Details: 1-800-49-GAMES or 607-652-9038 The New York Science Fiction Society — The Lunarians, Inc. presents: Lunacon 1995 March 17 - 19 Rye Town Hilton Rye Brook, New York Writer Guest of Honor Poul Anderson Artist Guest of Honor Stephen F. Hickman Fan Guest of Honor: Mike Glyer Featured Filker: Graham Leathers I TOR SALUTES LUNACON GUEST OF HONOR POUL ANDERSON the Hugo and Nebula-award winning SF Grand Master! Don’t miss THE STARS ARE ALSO FIRE, Poul Anderson’s -

By Tom Shippey; Bob Shaw - the Family Photographs; and MORE

More journeys into the Number 20: history of science fiction Autumn 2012 fandom in Britain. RELAPSE “Another totally absorbing issue full of fascinating information. I love it!” - Don Allen, e-mail comment. INSIDE: ‘A Truly Generous Chap’ by Ian Watson; ‘New Worlds for Old’ by Charles Platt; ‘Out of this World’ by Mike Ashley; ‘Goodbye, Harry!’ by Tom Shippey; Bob Shaw - the family photographs; AND MORE........ RELAPSE Oh dear, eighteen months since the last issue. That’s much too long, and just when 1 was generating a nice bit of momentum in my quest for stories about the people & places who have shaped British science fiction and its attendant fandom. Must do better! But please keep telling those tales to me, Peter Weston, at 53 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, B74 2PS; or by e-mail to pr.westonfa,blinternet.com. This is the printed edition for the favoured few who contribute, express interest or can’t switch on a computer, but I’ll send the pdf on request and it goes onto the eFanzines website a month after publication. “...the mixture as before, in the best possible way; history mixed with anecdote to result in a cracking read.” - Sandra Bond, LoC You may be reeling in shock because for the first time since issue #3 there’s no Giles cartoon on the cover. No, not a policy change but just my taking merciless advantage of something Ian Watson wrote in a brief LoC on the last issue: “Not much of a send-off for ‘poor old Brunner’ what with your deciding that he didn’t achieve all that much really, and some geezer calling him a pratt (evidently worse than your usual prat). -

Foundation Review of Science Fiction 125 Foundation the International Review of Science Fiction

The InternationalFoundation Review of Science Fiction 125 Foundation The International Review of Science Fiction In this issue: Jacob Huntley and Mark P. Williams guest-edit on the legacy of the New Wave A previously unpublished interview with Michael Moorcock Brian Baker tours Europe with Brian Aldiss Jonathan Barlow conjures with Elric, Jerry Cornelius and Lord Horror Foundation Nick Hubble on the persistence of New Wave-forms in Christopher Priest Peter Higgins is inspired by Gene Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun Gwyneth Jones revisits aliens and the Aleutians 45.3 Volume Conference reports from Kerry Dodd and Gul Dag In addition, there are reviews by: number 125 Jeremy Brett, Kanta Dihal, Carl Freedman, Jennifer Harwood-Smith, Nick Hubble, Carl Kears, Paul Kincaid, Sandor Klapcsik, Chris Pak, Umberto Rossi, Alison Tedman and Juha Virtanen 2016 Of books by: Anne Hiebert Alton and William C. Spruiell, Martyn Amos and Ra Page, Gerry Canavan and Kim Stanley Robinson, Brian Catling, Sonja Fritzsche, Ian McDonald, Paul March-Russell, China Miéville, Carlo Pagetti, Hannu Rajaniemi, Tricia Sullivan and Gene Wolfe Special section on Michael Moorcock and the New Wave Cover image/credit: Mal Dean, cover to the original hardback edition of Michael Moorcock, The Final Programme (Allison & Busby, 1968) Foundation is published three times a year by the Science Fiction Foundation (Registered Charity no. 1041052). It is typeset and printed by The Lavenham Press Ltd., 47 Water Street, Lavenham, Suffolk, CO10 9RD. Foundation is a peer-reviewed journal. Subscription rates for 2017 Individuals (three numbers) United Kingdom £22.00 Europe (inc. Eire) £24.00 Rest of the world £27.50 / $42.00 (U.S.A.) Student discount £15.00 / $23.00 (U.S.A.) Institutions (three numbers) Anywhere £45.00 / $70.00 (U.S.A.) Airmail surcharge £7.50 / $12.00 (U.S.A.) Single issues of Foundation can also be bought for £7.00 / $15.00 (U.S.A.).