'”Don't Let the Side Down, Old Boy”: Interrogating The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Play Sets

Oxfordshire County Council List of Play Sets Available from the Oxford Central Library 2015 Oxford Central Library – W e s t g a t e – O x f o r d – O X 1 1 D J Author Title ISBN Copies Cast Genre Russell, Willy Shirley Valentine: A play T000020903 2 1f Comedy (Dramatic) Churchill, Caryl Drunk enough to say I love you? T000096352 3 2m Short Play, Drama Churchill, Caryl Number T000026201 3 2m Drama Fourie, Charles J. Parrot woman T000037314 3 1m, 1f Harris, Richard The business of murder T000348605 3 2m, 1f Mystery/Thriller Pinter, Harold The dumb waiter: a play T000029001 3 2m Short Play Plowman, Gillian Window cleaner: a play T000030648 3 1m, 1f Short Play Russell, Willy Educating Rita T000026217 3 1m, 1f Comedy (Dramatic) Russell, Willy Educating Rita T000026217 3 Simon, Neil They're playing our song T000024099 3 1m, 1f Musical; Comedy Tristram, David Inspector Drake and the Black Widow: a comedy T000035350 3 2m, 1f Comedy Ayckbourn, A., and others Mixed doubles: An entertainment on marriage T000963427 4 2m, 1f Anthology Ayckbourn, Alan Snake in the grass: a play T000026203 4 3f Drama Bennett, Alan Green forms (from Office suite) N000384797 4 1m, 2f Short Play; Comedy Brittney, Lynn Ask the family: a one act play T000035640 4 2m, 1f Short Play; Period (1910s) Author Title ISBN Copies Cast Genre Brittney, Lynn Different way to die: a one act play T000035647 4 2m, 2f Short Play Camoletti, Marc; Happy birthday 0573111723 4 2m, 3f Adaptation; Comedy Cross, Beverley Chappell, Eric Passing Strangers: a comedy T000348606 4 2m, 2f Comedy (Romantic) -

Blue Remembered Hills by Dennis Potter Directed by Jamesine Livingstone

Skipton Little Theatre Skipton Players’ Present Blue Remembered Hills By Dennis Potter Directed By Jamesine Livingstone Tuesday 20th to Saturday 24th April 2010 Director’s notes From the Chairman Dennis Potter was born in 1935 in Gloucestershire. After National Service he won a place at New College, Oxford where he read Philosophy, Politics and Economics. Hello and welcome to our penultimate play of He became one of Britain’s most accomplished and acclaimed dramatists. His plays for television include this our anniversary season, celebrating 50 Blue Remembered Hills (1979), Brimstone and Treacle years of dramatic art at the Little Theatre. (commissioned in 1975 but banned until 1987), the series Pennies from Heaven (1978), The Singing Detective (1986), Blackeyes (1989) and Lipstick on Your Collar (1993). He also wrote novels, stage plays and screenplays. He died Next month on Saturday May 15th here We are always wanting to invite anyone Dennis Potter in June 1994. in the Little Theatre we are putting on who would like to help in any of our Some television drama ages badly: even the most revered classics creak a bit when watched again a fond remembrance in the form of an productions in any capacity whatever (no in the cold, contemporary, high-definition light of day. This does not apply to Dennis Potter’s 1979 television film Blue Remembered Hills. It was part of the ‘Play For Today’ strand, and it originally evening of “Nosh and Neuralgia”, sorry experience necessary!) from helping on lasted an hour and a quarter. Being Potter it looks without romanticism and with an analytical eye that should be “Nosh and Nostalgia” the door, selling refreshments, backstage at the long summer days of childhood during the war. -

Dennis Potter: an Unconventional Dramatist

Dennis Potter: An Unconventional Dramatist Dennis Potter (1935–1994), graduate of New College, was one of the most innovative and influential television dramatists of the twentieth century, known for works such as single plays Son of Man (1969), Brimstone and Treacle (1976) and Blue Remembered Hills (1979), and serials Pennies from Heaven (1978), The Singing Detective (1986) and Blackeyes (1989). Often controversial, he pioneered non-naturalistic techniques of drama presentation and explored themes which were to recur throughout his work. I. Early Life and Background He was born Dennis Christopher George Potter in Berry Hill in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire on 17 May 1935, the son of a coal miner. He would later describe the area as quite isolated from everywhere else (‘even Wales’).1 As a child he was an unusually bright pupil at the village primary school (which actually features as a location in ‘Pennies From Heaven’) as well as a strict attender of the local chapel (‘Up the hill . usually on a Sunday, sometimes three times to Salem Chapel . .’).2 Even at a young age he was writing: I knew that the words were chariots in some way. I didn’t know where it was going … but it was so inevitable … I cannot think of the time really when I wasn’t [a writer].3 The language of the Bible, the images it created, resonated with him; he described how the local area ‘became’ places from the Bible: Cannop Ponds by the pit where Dad worked, I knew that was where Jesus walked on the water … the Valley of the Shadow of Death was that lane where the overhanging trees were.4 I always fall back into biblical language, but that’s … part of my heritage, which I in a sense am grateful for.5 He was also a ‘physically cowardly’6 and ‘cripplingly shy’7 child who felt different from the other children at school, a feeling heightened by his being academically more advanced. -

Authenticity and Englishness in the Films of Mike Leigh

Authenticity and Englishness in the Films of Mike Leigh 著者名(英) Anthony Mills journal or The Kyoritsu journal of international studies publication title volume 29 page range 123-143 year 2012-03 URL http://id.nii.ac.jp/1087/00002285/ Creative Commons : 表示 - 非営利 - 改変禁止 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.ja Authenticity and Englishness in the Films of Mike Leigh Anthony Mills What you see in my films you mostly don't see in movies. As a kid in the '40s and '50s, I would sit in movies endlessly ... and think wouldn't it be great if you could see people in films like peo- ple actually are? Mike Leigh, The Salon Interview 1 I don't make films that are exclusively or idiosyncratically English; the subject matter of my films is not English, but universal. Mike Leigh, quoted in Movshovitz 2 Introduction In a 2008 interview for BAFTA (The British Academy of Film and Television Arts), the English movie director, Mike Leigh, recalled a moment of truth that he experienced during a life painting class at the Camberwell Art School in London in the mid 1960s.3 He had moved to London from Manchester in 1960, intending to train as an actor. At first, he attended RADA (the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts), but he found the experience very unsatisfactory. In Leigh's opinion, RADA's teaching was based on old-fashioned and unsuitable methods. In par ticular, he felt that there was no room for actors to bring their own interpretation of characters or experience of life into the process of creating a film or play. -

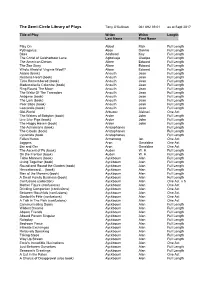

The Semi-Circle Library of Plays Tony O'sullivan 061 692 39 01 As at Sept 2017

The Semi-Circle Library of Plays Tony O'Sullivan 061 692 39 01 as at Sept 2017 Title of Play Writer Writer Length Last Name First Name . Play On Abbot Rick Full Length Pythagorus Abse Dannie Full Length Bites Adshead Kay Full Length The Christ of Coldharbour Lane Agboluaje Oladipo Full Length The American Dream Albee Edward Full Length The Zoo Story Albee Edward Full Length Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Albee Edward Full Length Ardele (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Restless Heart (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Time Remembered (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Mademoiselle Colombe (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Ring Round The Moon Anouilh Jean Full Length The Waltz Of The Toreadors Anouilh Jean Full Length Antigone (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length The Lark (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Poor Bitos (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Leocardia (book) Anouilh Jean Full Length Old-World Arbuzov Aleksei One Act The Waters of Babylon (book) Arden John Full Length Live Like Pigs (book) Arden John Full Length The Happy Haven (book) Arden John Full Length The Acharnians (book) Aristophanes Full Length The Clouds (book) Aristophanes Full Length Lysistrata (book Aristophanes Full Length Fallen Heros Armstrong Ian One Act Joggers Aron Geraldine One Act Bar and Ger Aron Geraldine One Act The Ascent of F6 (book) Auden W. H. Full Length On the Frontier (book) Auden W. H. Full Length Table Manners (book) Ayckbourn Alan Full Length Living Together (book) Ayckbourn Alan Full Length Round and Round the Garden (book) Ayckbourn Alan Full Length Henceforward... -

Epistolary Encounters: Diary and Letter Pastiche in Neo-Victorian Fiction

Epistolary Encounters: Diary and Letter Pastiche in Neo-Victorian Fiction By Kym Michelle Brindle Thesis submitted in fulfilment for the degree of PhD in English Literature Department of English and Creative Writing Lancaster University September 2010 ProQuest Number: 11003475 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003475 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis examines the significance of a ubiquitous presence of fictional letters and diaries in neo-Victorian fiction. It investigates how intercalated documents fashion pastiche narrative structures to organise conflicting viewpoints invoked in diaries, letters, and other addressed accounts as epistolary forms. This study concentrates on the strategic ways that writers put fragmented and found material traces in order to emphasise such traces of the past as fragmentary, incomplete, and contradictory. Interpolated documents evoke ideas of privacy, confession, secrecy, sincerity, and seduction only to be exploited and subverted as writers idiosyncratically manipulate epistolary devices to support metacritical agendas. Underpinning this thesis is the premise that much literary neo-Victorian fiction is bound in an incestuous relationship with Victorian studies. -

Zenker, Stephanie F., Ed. Books For

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 415 506 CS 216 144 AUTHOR Stover, Lois T., Ed.; Zenker, Stephanie F., Ed. TITLE Books for You: An Annotated Booklist for Senior High. Thirteenth Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-0368-5 ISSN ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 465p.; For the 1995 edition, see ED 384 916. Foreword by Chris Crutcher. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 03685: $16.95 members, $22.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC19 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Adolescents; Annotated Bibliographies; *Fiction; High School Students; High Schools; *Independent Reading; *Nonfiction; *Reading Interests; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Motivation; Recreational Reading; Thematic Approach IDENTIFIERS Multicultural Materials; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Designed to help teachers, students, and parents identify engaging and insightful books for young adults, this book presents annotations of over 1,400 books published between 1994 and 1996. The book begins with a foreword by young adult author, Chris Crutcher, a former reluctant high school reader, that discusses what books have meant to him. Annotations in the book are grouped by subject into 40 thematic chapters, including "Adventure and Survival"; "Animals and Pets"; "Classics"; "Death and Dying"; "Fantasy"; "Horror"; "Human Rights"; "Poetry and Drama"; "Romance"; "Science Fiction"; "War"; and "Westerns and the Old West." Annotations in the book provide full bibliographic information, a concise summary, notations identifying world literature, multicultural, and easy reading title, and notations about any awards the book has won. -

John Byrne's Scotland Paul Elliott, University of Worcester

Its Only Rock and Roll: John Byrne’s Scotland Paul Elliott, University of Worcester …I was brought up in Ferguslie Park housing scheme and found myself at the age of fourteen or so rejoicing in that fact and not really understanding why…Only later did I realise that I had been handed the greatest gift a budding painter/playwright could ever have…an enormous ‘treasure trove’ of language, oddballs, crooks, twisters, comics et al…into which I could dip a hand and pull out a mittful of gold dust. (Byrne 2014: 23) John Patrick Byrne was born six days into 1940 and grew up in the Ferguslie Park area of Glasgow. His father earned a living through a series of laboring and manual jobs and his mother was an usherette at the Moss Park Picture House. Byrne took to painting and drawing from an early age and recounts his mother stating that he began drawing in the pram as she wheeled him around the housing estate where they lived. As evidenced by the quote above, Byrne constantly drew on the people he met and saw in his early childhood for his art, and much of his later work can be seen to reflect this child-like vision of the world. When he was in his late childhood, Byrne’s mother was diagnosed with schizophrenia and taken to the Riccartsbar Mental Hospital in Paisley. This had an enormous impact on the young artist’s development and his creative output would be peppered with images of feminine abandonment and women with fragile mental states. -

British Films 1971-1981

Preface This is a reproduction of the original 1983 publication, issued now in the interests of historical research. We have resisted the temptations of hindsight to change, or comment on, the text other than to correct spelling errors. The document therefore represents the period in which it was created, as well as the hard work of former colleagues of the BFI. Researchers will notice that the continuing debate about the definitions as to what constitutes a “British” production was topical, even then, and that criteria being considered in 1983 are still valid. Also note that the Dept of Trade registration scheme ceased in May 1985 and that the Eady Levy was abolished in the same year. Finally, please note that we have included reminders in one or two places to indicate where information could be misleading if taken for current. David Sharp Deputy Head (User Services) BFI National Library August 2005 ISBN: 0 85170 149 3 © BFI Information Services 2005 British Films 1971 – 1981: - back cover text to original 1983 publication. What makes a film British? Is it the source of its finance or the nationality of the production company and/or a certain percentage of its cast and crew? Is it possible to define a British content? These were the questions which had to be addressed in compiling British Films 1971 – 1981. The publication includes commercial features either made and/or released in Britain between 1971 and 1981 and lists them alphabetically and by year of registration (where appropriate). Information given for each film includes production company, studio and/or major location, running time, director and references to trade paper production charts and Monthly Film Bulletin reviews as source of more detailed information. -

6/13/2010 Dvdsiv Page 1 TITLE * = in a Large Case, Or Multiple Movies On

DVDsIV 6/13/2010 TITLE * = In a large case, or multiple movies on 1 disc * Treasures Of Black:Devils Daughter,Gang Wars,Bronze Buck,UpInAir *And then there were none: Classic Mystery Movie * *Angel One Five / King & Country * *At War With The Army: Dean Martin: Stage And Screen *Aztec Temple Of Blood: Unsolved History *BangBros / Playboy Sizzlers / Ancient Secrets of Kama Sutra * *Battler, The/Bang The Drum Slowly (Paul Newman) * *Birth of a Nation *Black :Pacific Inferno,Death Of Prophet,TNT Jackson,Black Fist * *Body And Soul: Paul Robeson 2 * *Borderline: Paul Robeson 2 * *Caesar And Claretta / The Apple Cart ( Helen Mirren ) * *Carole Lombard 1: Man Of The World - We're Not Dressing *Carole Lombard 2: Hands Across The Table *Carole Lombard 3: Love Before Breakfast, Princess Comes Across * *Carole Lombard 4: True Confession *Classic Disaster Movies: Virus; Hurricane; Deadly Harvest * *Cry Panic: Classic Mystery Movie *Death Defying Acts / Houdini's Death Defying Acts *Emperor Jones: Paul Robeson 1 * *Empire of The Air, Ken Burns' America *Five Million Years To Earth (Quatermass And The Pit) *Giant Of Marathon / War Of The Trojans * *Go For Broke / Beyond Barbed Wire * *Great Bank Hoax / Great Bank Robbery * *HammerIcons: StopMe;Cash Demand;Snorkel;Maniac;NeverCandy;Damned *Huey Long: Ken Burns' America *Human Beast (The La Bete Humaine) *In Search of Cezanne/The Bolero * *Japan At War: Black Rain,Father Kamikaze,Japan's Longest,Okinawa *Jeopardy / To Please A Lady * *Jerico: Paul Robeson 3 * *Kill Da Wabbit (part of Looney Tunes Collection) -

Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn As Restoration Virtuosi

SAMUEL PEPYS AND JOHN EVELYN AS RESTORATION VIRTUOSI (with particular reference to the evidence in their diaries) by BERNARD GEORGE WEBBER B.A. University of British Columbia, 1950 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard The University of British Columbia October, 1962 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of English The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 8, Canada. Date October 4, 1962 V STATEMENT OF THESIS After the civil conflicts of the seventeenth century, England during the Restoration period began to emerge as a modern nation* As Charles II understood, and as James II was to learn at the cost,of his throne, absolute monarchy was no longer acceptable to the kingdom. Although Englishmen might henceforth tolerate the ,- ( trappings of absolutism, the substance was irrevocably gone. This 1 was as true of absolutism in religion as it was in government. It was only a question of time before the demands of Englishmen for freedom in belief and for participation in government would find expression in parliamentary democracy and in religious toleration. -

Ola Rotimi Postal Museum of World Famous Playwrights

SOCIETY OF YOUNG NIGERIAN WRITERS OLA ROTIMI POSTAL MUSEUM OF WORLD FAMOUS PLAYWRIGHTS Compiled by: Wole Adedoyin Edward Albee Edward Albee, born in 1928, American playwright, whose most successful plays focus on familial relationships. Edward Franklin Albee was born in Washington, D.C., and adopted as an infant by the American theater executive Reed A. Albee of the Keith-Albee chain of vaudeville and motion picture theaters. Albee attended a number of preparatory schools and, for a short time, Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut. He wrote his first one-act play, The Zoo Story (1959), in three weeks. Among his other plays are the one-act The American Dream (1961); Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962); The Ballad of the Sad Café (1963), adapted from a novel by the American author Carson McCullers; Tiny Alice (1964); and A Delicate Balance (1966), for which he won the 1967 Pulitzer Prize in drama. For Seascape (1975), which had only a brief Broadway run, Albee won his second Pulitzer Prize. His later works include The Lady from Dubuque (1977), an adaptation (1979) of Lolita by the Russian American novelist Vladimir Nabokov, and The Man Who Had Three Arms (1983). In 1994 he received a third Pulitzer Prize for Three Tall Women (1991). Albee won a Tony Award in 2002 for The Goat, or Who is Sylvia (2002), a play about a happily married architect who falls in love with a goat. Albee’s plays are marked by themes typical of the theater of the absurd, in which characters suffer from an inability or unwillingness to communicate meaningfully or to sympathize or empathize with one another.