Authenticity and Englishness in the Films of Mike Leigh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS of FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and Counting…

5 JAN 18 1 FEB 18 1 | 5 JAN 18 - 1 FEB 18 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECinema.COM CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS OF FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and counting… As you’ll spot deep within this programme (and hinted at on the front cover) January 2018 sees the start of a series of films that lead up to celebrations in October marking the 40th birthday of Filmhouse as a public cinema on Lothian Road. We’ve chosen to screen a film from every year we’ve been bringing the very best cinema to the good people of Edinburgh, and while it is tremendous fun looking back through the history of what has shown here, it was quite an undertaking going through all the old programmes and choosing what to show, and a bit of a personal journey for me as one who started coming here as a customer in the mid-80s (I know, I must have started very young...). At that time, I’d no idea that Filmhouse had only been in existence for less than 10 years – it seemed like such an established, essential institution and impossible to imagine it not existing in a city such as Edinburgh. My only hope is that the cinema is as important today as I felt it was then, and that the giants on whose shoulders we currently stand feel we’re worthy of their legacy. I hope you can join us for at least some of the screenings on this trip down memory lane... And now, back to the now. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Loving Attitudes by Rachel Billington Loving Attitudes by Rachel Billington

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Loving Attitudes by Rachel Billington Loving Attitudes by Rachel Billington. ‘One Summer is a real emotional roller-coaster of a read, and Billington expertly sustains the suspense.’ Daily Mail. Available to order. One Summer is unashamedly a tragic love story. Great passion is a theme I return to every decade or so. (For example, my earlier book, based on Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Occasion of Sin.) Of course it is a theme recurring in all fiction over the centuries. In this case the man, K, is twenty four years older than his love object who is still a school girl – and a naïve school girl at that. I have, however, not just written about the love affair but about its consequences fourteen years on so that the story is told in two different time-scales. It is also told in two voices – the male and the female. Part of the book is set in Valparaiso, Chile, where I stayed with my daughter, Rose Gaete, and my Chilean son-in-law just as I started writing the novel. Chance experience always plays a big part in what goes into my novels, although my characters are virtually never drawn directly from life. ‘Writing with grace and unflinching intensity, Billington acknowledges the complexity of cause and effect in a novel that is as much about the sufferings of expiation as the joys of passion.’ Sunday Times. ‘One Summer is a real emotional roller-coaster of a read, and Billington expertly sustains the suspense.’ Daily Mail. ‘Reading One Summer is an intense, even a claustrophobic experience: there is no escape, no let up, no Shakespearian comic gravedigger to lighten the tension. -

'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Glasgow School of Art: RADAR 'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir) David Sweeney During the Britpop era of the 1990s, the name of Mike Leigh was invoked regularly both by musicians and the journalists who wrote about them. To compare a band or a record to Mike Leigh was to use a form of cultural shorthand that established a shared aesthetic between musician and filmmaker. Often this aesthetic similarity went undiscussed beyond a vague acknowledgement that both parties were interested in 'real life' rather than the escapist fantasies usually associated with popular entertainment. This focus on 'real life' involved exposing the ugly truth of British existence concealed behind drawing room curtains and beneath prim good manners, its 'secrets and lies' as Leigh would later title one of his films. I know this because I was there. Here's how I remember it all: Jarvis Cocker and Abigail's Party To achieve this exposure, both Leigh and the Britpop bands he influenced used a form of 'real world' observation that some critics found intrusive to the extent of voyeurism, particularly when their gaze was directed, as it so often was, at the working class. Jarvis Cocker, lead singer and lyricist of the band Pulp -exemplars, along with Suede and Blur, of Leigh-esque Britpop - described the band's biggest hit, and one of the definitive Britpop songs, 'Common People', as dealing with "a certain voyeurism on the part of the middle classes, a certain romanticism of working class culture and a desire to slum it a bit". -

Mike Leigh La Vie… Et Rien D’Autre

Document generated on 09/24/2021 6:51 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma Mike Leigh La vie… et rien d’autre Number 187, November–December 1996 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/49412ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document (1996). Mike Leigh : la vie… et rien d’autre. Séquences, (187), 13–14. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 1996 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ r\ I T D C \/ I I C C Mike Leigh L/WIEa, ET RIEN 1 D'AUTRE WÊ Issu du milieu des théâtres expérimentaux où il participe à plusieurs recherches, Mike Leigh réalise Bleak Moments en 1970 et deux ans plus tard, reçoit le Grand Prix à Chicago et à Locarno pour ce film. Par la suite, il signe de nombreux téléfilms, notamment pour la BBC et Channel Four. En 1988, avec High Hopes, il se remet activement à tourner pour le cinéma. En 1993, il remporte le Prix de la mise en scène à Cannes pour Naked. Son tout dernier film, Secrets and Lies, a obtenu la Palme d'or cette année au même festival. -

March 19, 2013 (XXVI:9) Mike Leigh, NAKED (1994, 131 Min.)

March 19, 2013 (XXVI:9) Mike Leigh, NAKED (1994, 131 min.) Best Director (Leigh), Best Actor (Thewliss), Cannes 1993 Directed and written by Mike Leigh Written by Mike Leigh Produced by Simon Channing Williams Original Music by Andrew Dickson Cinematography by Dick Pope Edited by Jon Gregory Production Design by Alison Chitty Art Direction by Eve Stewart Costume Design by Lindy Hemming Steadicam operator: Andy Shuttleworth Music coordinator: Step Parikian David Thewlis…Johnny Lesley Sharp…Louise Clancy Jump, 2010 Another Year, 2008 Happy-Go-Lucky, 2004 Vera Katrin Cartlidge…Sophie Drake, 2002 All or Nothing, 1999 Topsy-Turvy, 1997 Career Girls, Greg Cruttwell…Jeremy G. Smart 1996 Secrets & Lies, 1993 Naked, 1992 “A Sense of History”, Claire Skinner…Sandra 1990 Life Is Sweet, 1988 “The Short & Curlies”, 1988 High Hopes, Peter Wight…Brian 1985 “Four Days in July”, 1984 “Meantime”, 1982 “Five-Minute Ewen Bremner…Archie Films”, 1973-1982 “Play for Today” (6 episodes), 1980 BBC2 Susan Vidler…Maggie “Playhouse”, 1975-1976 “Second City Firsts”, 1973 “Scene”, and Deborah MacLaren…Woman in Window 1971 Bleak Moments/ Gina McKee…Cafe Girl Carolina Giammetta…Masseuse ANDREW DICKSON 1945, Isleworth, London, England) has 8 film Elizabeth Berrington…Giselle composition credits: 2004 Vera Drake, 2002 All or Nothing, 1996 Darren Tunstall…Poster Man Secrets & Lies, 1995 Someone Else's America, 1994 Oublie-moi, Robert Putt...Chauffeur 1993 Naked, 1988 High Hopes, and 1984 “Meantime.” Lynda Rooke…Victim Angela Curran...Car Owner DICK POPE (1947, Bromley, -

Professor Robert Beveridge FRSA, University of Sassari

Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Relations Committee Scotland’s Screen Sector Written submission from Professor Robert Beveridge FRSA, University of Sassari 1. Introduction While it is important that the Scottish Parliament continues to investigate and monitor the state of the creative and screen industries in Scotland, the time has surely come for action rather than continued deliberation(s) The time has surely come when we need to stop having endless working parties and spending money on consultants trying to work out what to do. Remember the ‘Yes Minister’ Law of Inverse Relevance ‘ ‘The less you intend to do about something, the more you have to keep talking about it ‘ ‘Yes Minister’ Episode 1: Open Government Therefore, please note that we already know what to do. That is: 1.1 - Appoint the right people with the vision leadership and energy to succeed. 1.2 - Provide a positive legislative/strategic/policy framework for support. 1.3 - Provide better budgets and funding for investment and/or leverage for the same. (You already have access to the data on existing funding for projects and programmes of all kinds. If the Scottish Government wishes to help to improve performance in the screen sector, there will need to be a step change in investment. There is widespread agreement that more is needed.) 1.4 Give them space to get on with it. That is what happened with the National Theatre of Scotland. This is what happened with MG Alba. Both signal success stories. Do likewise with the Screen Industries in Scotland 2. Context Some ten years ago the Scottish Government established the Scottish Broadcasting Commission. -

Press Release 12 January 2016

Press Release 12 January 2016 (For immediate release) SIDNEY POITIER TO BE HONOURED WITH BAFTA FELLOWSHIP London,12 January 2016: The British Academy of Film and Television Arts will honour Sir Sidney Poitier with the Fellowship at the EE British Academy Film Awards on Sunday 14 February. Awarded annually, the Fellowship is the highest accolade bestowed by BAFTA upon an individual in recognition of an outstanding and exceptional contribution to film, television or games. Fellows previously honoured for their work in film include Charlie Chaplin, Alfred Hitchcock, Steven Spielberg, Sean Connery, Elizabeth Taylor, Stanley Kubrick, Anthony Hopkins, Laurence Olivier, Judi Dench, Vanessa Redgrave, Christopher Lee, Martin Scorsese, Alan Parker and Helen Mirren. Mike Leigh received the Fellowship at last year’s Film Awards. Sidney Poitier said: “I am extremely honored to have been chosen to receive the Fellowship and my deep appreciation to the British Academy for the recognition.” Amanda Berry OBE, Chief Executive of BAFTA, said: “I’m absolutely thrilled that Sidney Poitier is to become a Fellow of BAFTA. Sidney is a luminary of film whose outstanding talent in front of the camera, and important work in other fields, has made him one of the most important figures of his generation. His determination to pursue his dreams is an inspirational story for young people starting out in the industry today. By recognising Sidney with the Fellowship at the Film Awards on Sunday 14 February, BAFTA will be honouring one of cinema’s true greats.” Sir Sidney Poitier’s award-winning career features six BAFTA nominations, including one BAFTA win, and a British Academy Britannia Award for Lifetime Contribution to International Film. -

CC-Film-List

CC’s (incomplete, constantly evolving) list of “must-see” filmmakers and their films Buster Keaton: The General; Sherlock, Jr.; Steamboat Bill, Jr.; The High Sign; Our Hospitality Lucretia Martel: The Swamp; The Holy Girl; The Headless Woman Hirokazu Kore-Eda: Maborosi; Afterlife; Nobody Knows; Still Walking Terence Davies: Distant Voices, Still Lives; The Long Day Closes, The House of Mirth, The Deep Blue Sea Charles Burnett: Killer of Sheep; To Sleep with Anger Agnes Varda: Cleo From Five to Seven, The Vagabond; The Beaches of Agnes; The Gleaners & I Douglas Sirk: Written on the Wind; All That Heaven Allows; The Tarnished Angels Todd Haynes: Safe; Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story; Far From Heaven John Ford: Stagecoach: My Darling Clementine; The Searchers Vittorio de Sica: Bicycle Thieves; Shoeshine; Umberto D; Roberto Rossellini: Rome, Open City; Paisan; Journey to Italy Luis Buñuel: Un Chien Andalou (with Salvador Dali); Los Olvidados; Illusion Travels by Streetcar: That Obscure Object of Desire; Viridiana; Belle du Jour; The Exterminating Angel Kelly Reichardt: Old Joy; Wendy & Lucy; Meek’s Cut-off; Night Moves John Greyson: Zero Patience; Lillies Sally Potter: Orlando; Yes; Ginger and Rosa Theo Angelopoulos: The Suspended Step of the Stork; Landscape in the Midst Ousmane Sembene: Moolaadé; Faat Kiné; Guelwaar Orson Welles: Citizen Kane; The Magnificent Ambersons; Touch of Evil; The Lady from Shanghai; Chimes at Midnight Zhangke Jia: The World; Still Life; Platform Ken Loach: Riff-Raff; Kes; The Navigators, Raining Stones; My -

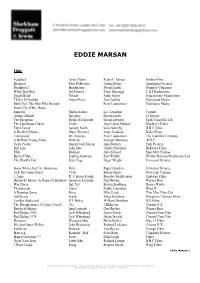

Eddie Marsan

EDDIE MARSAN Film: Feedback Jarvis Dolan Pedro C Alonso Ombra Films Backseat Paul Wolfowitz Adam Mckay Annapurna Pictures Deadpool 2 Headmaster David Leitch Donners' Company White Boy Rick Art Derrick Yann Demange L B I Productions Jungle Book Vihaan Andy Serkis Imaginarium Productions 7 Days In Entebbe Simon Peres Jose Padilha Participant Media Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Peter Landesman Endurance Media Down The White House Emperor Martin Luther Lee Tamahori Corrino Atomic Blonde Spyglass David Leitch 87 Eleven The Exception Heinrich Himmler David Leveaux Egoli Tossell K L K The Limehouse Golem Uncle Juan Carlos Medina Number 9 Films Their Finest Sammy Smith Lone Scherfig B B C Films A Kind Of Murder Marty Kimmel Andy Goddard Killer Films Concussion Dr. Dekosky Peter Landesman The Cantillon Company A Brilliant Young Mind Richard Morgan Matthews B B C God's Pocket Smilin' Jack Moran John Slattery Park Pictures Still Life John May Uberto Passolini Redwave Films Filth Bladesy John S Baird Steel Mill Pictures Best Of Men Ludwig Guttman Tim Whitby Whitby Davison Productions Ltd The World's End Peter Page Edgar Wright Universal Pictures Snow White And The Huntsman Duir Rupert Sanders Universal Pictures Jack The Giant Slayer Craw Bryan Singer New Line Cinema I, Anna D. I. Kevin Franks Barnaby Southcombe Embargo Films Sherlock Holmes: A Game Of Shadows Inspector Lestrade Guy Ritchie Warner Bros War Horse Sgt. Fry Steven Spielberg Dream Works Tyrannosaur James Paddy Considine Warp X A Running Jump Perry Mike Leigh Thin Man Films Ltd Junkhearts Frank Tinge Krishnan Disruptive Element Films London Boulevard D I. -

'”Don't Let the Side Down, Old Boy”: Interrogating The

‘Don’t let the side down, old boy’: Interrogating the Traitor in the ‘Radical’ Television Dramas of John le Carré and Dennis Potter Dr Joseph Oldham To cite this article, please use the version published in Cold War History (2019): https://doi.org/10.1080/14682745.2019.1638366. Introduction In an article suggesting future possibilities for research on Britain’s cultural Cold War, Tony Shaw concludes by pondering whether, for instance, television scriptwriters might have played a role in prolonging geopolitical tensions ‘by fostering antipathy between East and West’.1 The offhand assumption of television drama as predominantly conservative, shoring up an orthodox Cold War consensus, is significant and not without some basis. In the USA, the Second Red Scare saw the appearance numerous staunchly anti-communist spy series including I Led 3 Lives (Ziv, 1953-56) and Behind Closed Doors (NBC, 1958-59), frequently made with approval and assistance from the FBI, State Department and Department of Defence. The many British spy series which appeared over the 1960s, including Danger Man (ITV, 1960-66) and The Avengers (ITV, 1961-69), were generally not informed by such official connections.2 Nonetheless, their status as ‘products’ made with an eye on the export market encouraged a ‘reassuring’ formal model. In these series, heroes reliably overcame enemy threats on a weekly basis, affirming ‘the viewer’s faith in the value systems and moral codes which the hero represents.’3 Even John Kershaw, Associate Producer on the spy series Callan (ITV, 1967-72), eventually came to worry that its continual vilification of the Russians was ‘irresponsible’.4 Yet such genre series were only part of a diverse British broadcasting ecology still strongly rooted in public service values, and the medium’s most critically-admired output of this era typically lay elsewhere. -

Dennis Potter: an Unconventional Dramatist

Dennis Potter: An Unconventional Dramatist Dennis Potter (1935–1994), graduate of New College, was one of the most innovative and influential television dramatists of the twentieth century, known for works such as single plays Son of Man (1969), Brimstone and Treacle (1976) and Blue Remembered Hills (1979), and serials Pennies from Heaven (1978), The Singing Detective (1986) and Blackeyes (1989). Often controversial, he pioneered non-naturalistic techniques of drama presentation and explored themes which were to recur throughout his work. I. Early Life and Background He was born Dennis Christopher George Potter in Berry Hill in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire on 17 May 1935, the son of a coal miner. He would later describe the area as quite isolated from everywhere else (‘even Wales’).1 As a child he was an unusually bright pupil at the village primary school (which actually features as a location in ‘Pennies From Heaven’) as well as a strict attender of the local chapel (‘Up the hill . usually on a Sunday, sometimes three times to Salem Chapel . .’).2 Even at a young age he was writing: I knew that the words were chariots in some way. I didn’t know where it was going … but it was so inevitable … I cannot think of the time really when I wasn’t [a writer].3 The language of the Bible, the images it created, resonated with him; he described how the local area ‘became’ places from the Bible: Cannop Ponds by the pit where Dad worked, I knew that was where Jesus walked on the water … the Valley of the Shadow of Death was that lane where the overhanging trees were.4 I always fall back into biblical language, but that’s … part of my heritage, which I in a sense am grateful for.5 He was also a ‘physically cowardly’6 and ‘cripplingly shy’7 child who felt different from the other children at school, a feeling heightened by his being academically more advanced. -

Amitabh Bachchan Becomes the First Indian to Be Presented with the FIAF Award

For Immediate Dissemination Press Release Amitabh Bachchan Becomes the First Indian to Be Presented with the FIAF Award Martin Scorsese and Christopher Nolan to Congratulate the Indian Megastar at a Virtual Showcase India, 10th March 2021 - Indian film luminary Amitabh Bachchan will be conferred with the prestigious 2021 FIAF Award by the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF), the worldwide organization of film archives and museums from across the world, at a virtual showcase scheduled to take place on March 19, 2021. Mr. Bachchan’s name was nominated by the FIAF affiliate Film Heritage Foundation, a not-for-profit organization founded by filmmaker and archivist Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, dedicated to the preservation, restoration, documentation, exhibition, and study of India’s film heritage. In a landmark moment for Indian cinema, icons of world cinema and film directors Martin Scorsese and Christopher Nolan, who also share a long-standing relationship with India through their affiliation with Film Heritage Foundation, will bestow the award on Mr. Bachchan for his dedication and contribution to the preservation of, and access to, the world’s film heritage for the benefit of present and future generations, at a virtual presentation. The highly regarded National Award-winning film superstar will be the very first Indian to receive this esteemed global award. Previous recipients include legends of world cinema such as Martin Scorsese (2001), Manoel de Oliveira (2002), Ingmar Bergman (2003), Geraldine Chaplin (2004), Mike Leigh (2005), Hou Hsiao-hsien (2006), Peter Bogdanovich (2007), Nelson Pereira dos Santos (2008), Rithy Panh (2009), Liv Ullmann (2010), Kyoko Kagawa (2011), Agnès Varda (2013), Jan Švankmajer (2014), Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi (2015), Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne (2016), Christopher Nolan (2017), Apichatpong Weerasethakul (2018), Jean-Luc Godard (2019), and Walter Salles (2020).