Lihish'tah'weel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Download the Script. [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8585/download-the-script-pdf-18585.webp)

Download the Script. [Pdf]

The Empty Mirror screenplay by Barry Hershey and R. Buckingham Story by Barry Hershey Walden Woods Film Company, Inc. June 5, 1995 THE EMPTY MIRROR - final production script - June 5, 1995 p.1 FADE IN: 1 PROLOGUE - (ACCOMPANIED BY A WAGNERIAN OVERTURE) A SERIES OF GRAINY IMAGES Snow blows over dead soldiers in a road. A grainy image: A woman drags an emaciated corpse, its foot leaves a shallow furrow in the sand. A grief stricken mother caresses the face of her dead child. The images dissolve into a gray, swirling, grainy abstraction. 2 SWIRLING, OUT-OF-FOCUS SHAPES, BLACK AND WHITE On the sound track: VOICES, distorted, animalistic. The TITLE comes up over the abstract images. Some of the letters are runic, mystical. The title fades out. The VOICES distill to one familiar VOICE. The swirling shapes begin to focus as we MOVE back. We're watching a "screen" suspended in space. ON THE SCREEN: An impassioned man speaks to a rapt crowd of Hitler Youth. ADOLF HITLER, at the peak of his power. HITLER (German, no subtitles) We will pass from the scene, but for you, Germany will live on. And when we are gone, it will be your duty to hold high in your clenched fist the banner which we raised out of nothingness. And I know it cannot be otherwise, for you are flesh of our flesh and blood of our blood, and the same spirit that rules us burns in your young brains. Today, standing on this stage, I am but a tiny part of that which extends beyond, over the whole of Germany, and we want you, German boys and German girls, to absorb all our hopes for the future of that Germany. -

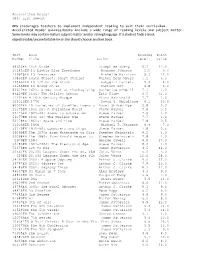

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Test List Report OHS encourages teachers to implement independent reading to suit their curriculum. Accelerated Reader quizzes/books include a wide range of reading levels and subject matter. Some books may contain mature subject matter and/or strong language. If a student finds a book objectionable/uncomfortable he or she should choose another book. Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 68630EN 10th Grade Joseph Weisberg 5.7 11.0 101453EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Maureen Johnson 5.0 9.0 136675EN 13 Treasures Michelle Harrison 5.3 11.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 135667EN 16 1/2 On the Block Babygirl Daniels 5.3 4.0 135668EN 16 Going on 21 Darrien Lee 4.8 6.0 53617EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 86429EN 1634: The Galileo Affair Eric Flint 6.5 31.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 7.7 1.0 104010EN 1776 David G. McCulloug 9.1 20.0 80002EN 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems o Naomi Shihab Nye 5.8 2.0 53175EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 53176EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Steve Parker 7.9 1.0 53177EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Steve Parker 7.7 1.0 53178EN 1960s: Space and Time Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 130068EN 1968 Michael T. Kaufman 9.9 7.0 53179EN 1970-90: Computers and Chips Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 36099EN The 1970s from Watergate to Disc Stephen Feinstein 8.2 1.0 36098EN The 1980s from Ronald Reagan to Stephen Feinstein 7.8 1.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Ad Jules Verne 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

Buddhism from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search

Buddhism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A statue of Gautama Buddha in Bodhgaya, India. Bodhgaya is traditionally considered the place of his awakening[1] Part of a series on Buddhism Outline · Portal History Timeline · Councils Gautama Buddha Disciples Later Buddhists Dharma or Concepts Four Noble Truths Dependent Origination Impermanence Suffering · Middle Way Non-self · Emptiness Five Aggregates Karma · Rebirth Samsara · Cosmology Practices Three Jewels Precepts · Perfections Meditation · Wisdom Noble Eightfold Path Wings to Awakening Monasticism · Laity Nirvāṇa Four Stages · Arhat Buddha · Bodhisattva Schools · Canons Theravāda · Pali Mahāyāna · Chinese Vajrayāna · Tibetan Countries and Regions Related topics Comparative studies Cultural elements Criticism v • d • e Buddhism (Pali/Sanskrit: बौद धमर Buddh Dharma) is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha (Pāli/Sanskrit "the awakened one"). The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE.[2] He is recognized by adherents as an awakened teacher who shared his insights to help sentient beings end suffering (or dukkha), achieve nirvana, and escape what is seen as a cycle of suffering and rebirth. Two major branches of Buddhism are recognized: Theravada ("The School of the Elders") and Mahayana ("The Great Vehicle"). Theravada—the oldest surviving branch—has a widespread following in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, and Mahayana is found throughout East Asia and includes the traditions of Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Shingon, Tendai and Shinnyo-en. In some classifications Vajrayana, a subcategory of Mahayana, is recognized as a third branch. -

War and the Results of War Films Look Inside Hitler's Bunker and at Shattered Vienna

War and the results of war Films look inside Hitler's bunker and at shattered Vienna By David Sterritt, Staff writer of The Christian Science Monitor | MAY 7, 1999 NEW YORK — World War II returned to movie screens with a vengeance in "Saving Private Ryan" and "The Thin Red Line" last year. While it's too early to say whether this trend will grow in the near future, two new releases take us back to the 1940s for sidelong explorations of the conflict and its aftermath. "The Empty Mirror" pays an impressionistic visit to Adolf Hitler skulking around his bunker as the Third Reich topples, while a 50th-anniversary reissue of "The Third Man" travels to postwar Vienna for a dramatic look at a shattered society. The Empty Mirror is set in the quarters where Hitler spent the last days before his apparent suicide. This single-setting format gives it a claustrophobic undertone that's darkly appropriate to Hitler's maniacal ideas. The movie is never monotonous, though, weaving a complex web of sounds and images around the riveting portrayal of Hitler by Norman Rodway, a British stage actor. Alternately ranting, brooding, haranguing, and whining, his stream-of-consciousness monologue provides the film with its transfixing core. Rodway also resembles comedian John Cleese just enough to evoke the tragic absurdity at the heart of Hitler's grotesque enterprise. Equally important is the visual fabric that surrounds Hitler, as he passes time watching Nazis newsreels, Holocaust atrocity films, and movies of his private moments and demagogic speeches. These images come and go with dreamlike unpredictability throughout the movie, punctuating its spoken material: the dictator's mental dialogues with his associates - his mistress, his propagandist, his military mastermind - and an imagined conversation with Sigmund Freud, whose psychological insights are closer to the mark than he can tolerate. -

Recordings by Women Table of Contents

'• ••':.•.• %*__*& -• '*r-f ":# fc** Si* o. •_ V -;r>"".y:'>^. f/i Anniversary Editi Recordings By Women table of contents Ordering Information 2 Reggae * Calypso 44 Order Blank 3 Rock 45 About Ladyslipper 4 Punk * NewWave 47 Musical Month Club 5 Soul * R&B * Rap * Dance 49 Donor Discount Club 5 Gospel 50 Gift Order Blank 6 Country 50 Gift Certificates 6 Folk * Traditional 52 Free Gifts 7 Blues 58 Be A Slipper Supporter 7 Jazz ; 60 Ladyslipper Especially Recommends 8 Classical 62 Women's Spirituality * New Age 9 Spoken 64 Recovery 22 Children's 65 Women's Music * Feminist Music 23 "Mehn's Music". 70 Comedy 35 Videos 71 Holiday 35 Kids'Videos 75 International: African 37 Songbooks, Books, Posters 76 Arabic * Middle Eastern 38 Calendars, Cards, T-shirts, Grab-bag 77 Asian 39 Jewelry 78 European 40 Ladyslipper Mailing List 79 Latin American 40 Ladyslipper's Top 40 79 Native American 42 Resources 80 Jewish 43 Readers' Comments 86 Artist Index 86 MAIL: Ladyslipper, PO Box 3124-R, Durham, NC 27715 ORDERS: 800-634-6044 M-F 9-6 INQUIRIES: 919-683-1570 M-F 9-6 ordering information FAX: 919-682-5601 Anytime! PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are tem CATALOG EXPIRATION AND PRICES: We will honor don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and porarily out of stock on a title, we will automatically prices in this catalog (except in cases of dramatic schools). Make check or money order payable to back-order it unless you include alternatives (should increase) until September. -

The World Hitler Never Made: Alternate History and the Memory of Nazism Gavriel D

Cambridge University Press 0521847060 - The World Hitler Never Made: Alternate History and the Memory of Nazism Gavriel D. Rosenfeld Frontmatter More information THE WORLD HITLER NEVER MADE What if the Nazis had triumphed in World War II? What if Adolf Hitler had escaped Berlin for the jungles of Latin America in 1945? What if Hitler had become a successful artist instead of a politician? Gavriel D. Rosenfeld’s pioneering study explores why such counter- factual questions on the subject of Nazism have proliferated in recent years within Western popular culture. Examining a wide range of novels, short stories, films, television programs, plays, comic books, and scholarly essays that have appeared in Great Britain, the United States, and Germany since 1945, Rosenfeld shows how the portrayal of historical events that never happened reflects the evolving memory of the Third Reich’s real historical legacy. He concludes that the shifting representation of Nazism in works of alternate history, as well as the popular reactions to them, highlights their subversive role in promoting the normalization of the Nazi past in Western memory. GAVRIEL D. ROSENFELD is Associate Professor of History at Fairfield University (Connecticut). He is a specialist in the history and memory of the Third Reich and the Holocaust. His previous publications include Munich and Memory: Architecture, Monuments, and the Legacy of the Third Reich (2000). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521847060 - The World Hitler Never Made: Alternate History and the Memory of Nazism Gavriel D. Rosenfeld Frontmatter More information THE WORLD HITLER NEVER MADE Alternate History and the Memory of Nazism GAVRIEL D. -

1 42.347 Dr. Stallbaumer-Beishline Holocaust Through Hollywood's

1 42.347 Dr. Stallbaumer-Beishline Holocaust through Hollywood's Eyes Holocaust Films: “Imagining the Unimaginable” The average American's most extensive exposure to the Holocaust is through popular filmic presentations on either the "big screen" or television. These forums, as Ilan Avisar points out, must yield “to popular demands and conventional taste to assure commercial success."1 Subsequently, nearing the successful completion of this course means that you know more about the Holocaust than the average American. This assignment encourages you to think critically, given your broadened knowledge base, about how the movie-television industry has treated the subject. Film scholars have grappled with the unique challenge of Holocaust-themed films. Ponder their views as you formulate your own opinions about the films that you select to watch. Annette Insdorff, Indelible Shadows: Film and the Holocaust (1989) "How great a role are films playing in determining contemporary awareness of the Final Solution? . How do you show people being butchered? How much emotion is too much? How will viewers respond to light-hearted moments in the midst of suffering?" (xviii) "How do we lead a camera or a pen to penetrate history and create art, as opposed to merely recording events? What are the formal as well as moral responsibilities if we are to understand and communicate the complexities of the Holocaust through its filmic representations?" (xv) Ilan Avisar, Screening the Holocaust: Cinema's Images of the Unimaginable (1988) "'Art [including film making] takes the sting out of suffering.'" (viii) The need for popular reception of a film inevitably leads to "melodramatization or trivialization of the subject." (46) Hollywood/American filmmakers' "universalization [using the Holocaust to make statements about contemporary problems] is rooted in specific social concerns that seek to avoid burdening a basically indifferent public with unbearable facts of the Nazi genocide of the Jews. -

Just a Man with a Little Moustache Las Parodias De Hitler En El

COLECCIÓN TESIS DIGITALES N° 1 TESIS DE GRADO Just a man with a little moustache: las parodias de Hitler en el cine. Milton Ekman 2020 Just a man with a little moustache; Las parodias de Hitler en el cine Milton Ekman Just a man with a little moustache; Las parodias de Hitler en el cine “La burla es el arma del neurótico para defenderse del perverso” El Periodista1 Universidad del Cine Buenos Aires 2020 Colección Tesis Digitales N°1 1 El Periodista. Diego Recalde (2011) Ekman, Milton Just a man with a little moustache : las parodias de Hitler en el cine / Milton Ekman ; prólogo de Rodolfo Orero. - 1a ed . - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires : Universidad del Cine, 2020. Libro digital, PDF - (Tesis digitales / 1) Archivo Digital: descarga y online ISBN 978-987-26443-2-1 1. Cine Contemporáneo. 2. Nazismo. 3. Comedia. I. Orero, Rodolfo, prolog. II. Título. CDD 791.43617 Contacto con el autor: [email protected] Contacto Editorial Universidad del Cine: [email protected] Consultar la actividad editorial de la Universidad del Cine Otros formatos disponibles: EPUB / MOBI ISBN: 978-987-26443-2-1 Hecho el depósito que marca la Ley 11.723 Colección Tesis Digitales N°1 . La Universidad del Cine autoriza la libre descarga y distribución del presente material sin fines comerciales, respetando la integridad del texto y citando su autor, título y editorial. Las opiniones y contenidos de la presente publicación no constituyen ni representan necesariamente el pensamiento institucional de la Universidad del Cine, sino que son de exclusiva responsabilidad del autor Prólogo En este ensayo, su tesis para la licenciatura en la Universidad del Cine, Milton Ekman analiza la representación de Adolf Hitler a través de la historia del cine. -

Filled with Hate Sat, 05/01/1999 – 01:00 a Review of "The Empty Mirror"

Filled with Hate Sat, 05/01/1999 – 01:00 A review of "The Empty Mirror". By Gentry Menzel Average: Barry J. Hershey's first full-length feature, "The Empty Mirror," takes place in a fantastical non-time parallel to Hitler's last days in his bunker in 1945. The story jumps off from an image that intrigued Boston-based Hershey: Hitler watching images of himself on film. What would he make of his life? How would he place himself in history? And, most interesting to Hershey, how would Hitler reconcile the icon of Hitler as German savior with the reality of millions killed, and the ultimate destruction and defeat of what he called the Motherland? To watch this film is to get inside Hitler's mind, to learn how he created the Hitler Myth, and to watch the icon ultimately crumble. The Hitler of "The Empty Mirror," as portrayed compellingly by Norman Rodway, is a control freak, the tyrannical director of a movie that would eventually engulf the world and redefine evil for the 20th century. To the accompaniment of continuously projected archival films--the Nazi uber-propaganda of Leni Riefenstahl's "Triumph of the Will," battle footage from the Russian front, Eva Braun's home movies--Hitler soliloquizes while a typist (Doug McKeon) records his words for posterity, and is visited by Eva Braun (Camilla Soeberg), Josef Goebbels (Joel Grey), Hermann Goehring (Glenn Shaddix), and Sigmund Freud (Peter Michael Goetz), with whom he discusses his beliefs and ideas. And although these visitations exist only in his increasing dementia, Hitler bullies, blusters, chastises, and, in the case of Braun, confesses almost romantic feelings. -

Film Journal International

EMPTY MIRROR, THE NR -By Ed Kelleher For movie details, please click here. Jan Kershaw, the noted biographer of Adolf Hitler, once listed that German dictator's principal characteristics as will, fantasy and brutality. All three of those attributes can be found in British actor Norman Rodway's spellbinding portrayal of the Fuhrer in The Empty Mirror, Barry J. Hershey's vivid, unsettling film, which imagines the final defeated days Hitler spent in a Berlin bunker at the end of World War II. A bold, demanding film that plunges the viewer into a realm of surrealist fantasy, The Empty Mirror isn't for the casual moviegoer, but it challenges the thoughtful viewer to look at Hitler through a prism detached from historical time. 'Germany is not worthy of me!' a dejected Hitler complains while pacing his underground retreat. Hershey's screenplay, written with R. Buckingham, imagines the German dictator as something of a cultural revisionist, wrestling with his own tortured psyche, dictating his memoirs, debating an imaginary Sigmund Freud (Peter Michael Goetz)-even committing a Freudian slip-and interacting with such phantoms as mistress Eva Braun (Camilla Soeberg), propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels (Joel Grey) and military mastermind Hermann Goering (Glenn Shadix). As played by Rodway of Royal Shakespeare Company renown, the Fuhrer is also something of a film revisionist, thanks to longtime David Lynch cinematographer Frederick Elmes, whose recently developed technology projects continuous images behind a constantly changing foreground. So while Rodway as Hitler bemoans his lot in life, we see an ongoing visual display- from German newsreels, Leni Riefenstahl's documentaries, even Braun's home movies-which provides a look at that life in a backgrounding flow behind the present narrative. -

Holocaust Filmography & Tvography

1 Holocaust through Hollywood's Eyes Dr. Stallbaumer-Beishline Hollywood is being defined here as produced in or by Americans or distributed to American audiences. Subsequently, most of the films are in English. The Holocaust may refer narrowly to the extermination of European Jews or more broadly victims of Nazi racism; perpetrators; bystanders; and post-war trials and tribulations of survivors, perpetrators, or bystanders. The Holocaust may be used as a plotting device that explains character motivations which raises question about the potential use or abuse of history in film. The list is divided into films or movies (Filmography) and made for television films or episodes (TVography). Wikipedia maintains a useful list: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Holocaust_films organized chronologically into films and documentaries. Filmography1 Adam Resurrected "In the aftermath of WWII, a former circus entertainer who was spared from the gas chamber becomes the ringleader at an asylum for Holocaust survivors." 2008. Amen "During WWII SS officer Kurt Gerstein tries to inform Pope Pius XII about Jews being sent to concentration camps. Young Jesuit priest Riccardo Fontana gives him a hand." Dir. Costa- Gavras. 2002. Apt Pupil “A boy blackmails his neighbour after suspecting him to be a Nazi war criminal.” 1998. The Aryan Couple (or The Couple) "A WWII Drama about a German/Jewish industrialist who, in order to ensure his family's safe passage out of Germany, is forced to hand over his business to the Nazis." 2004. The Assisi Underground "Based on the best-selling documentary novel, this film sheds light on the work done by the Catholic Church and the people of Assisi to rescue several hundred Italian Jews from Nazi execution following the German occupation of Italy in 1943." Dir. -

Synopsis CPL 1

General and PG titles Call: 1-800-565-1996 Criterion Pictures 30 MacIntosh Blvd., Unit 7 • Vaughan, Ontario • L4K 4P1 800-565-1996 Fax: 866-664-7545 • www.criterionpic.com 10,000 B.C. 2008 • 108 minutes • Colour • Warner Brothers Director: Roland Emmerich Cast: Nathanael Baring, Tim Barlow, Camilla Belle, Cliff Curtis, Joel Fry, Mona Hammond, Marco Khan, Reece Ritchie A prehistoric epic that follows a young mammoth hunter's journey through uncharted territory to secure the future of his tribe. The 11th Hour 2007 • 93 minutes • Colour • Warner Independent Pictures Director: Leila Conners Petersen, Nadia Conners Cast: Leonardo DiCaprio (narrated by) A look at the state of the global environment including visionary and practical solutions for restoring the planet's ecosystems. 13 Conversations About One Thing 2001 • 102 minutes • Colour • Mongrel Media Director: Jill Sprecher Cast: Matthew McConaughey, David Connolly, Joseph Siravo, A.D. Miles, Sig Libowitz, James Yaegashi In New York City, the lives of a lawyer, an actuary, a house-cleaner, a professor, and the people around them intersect as they ponder order and happiness in the face. of life's cold unpredictability. 16 Blocks 2006 • 102 minutes • Colour • Warner Brothers Director: Richard Donner Cast: Bruce Willis, Mos Def, David Morse, Alfre Woodard, Nick Alachiotis, Brian Andersson, Robert Bizik, Shon Blotzer, Cylk Cozart Based on a pitch by Richard Wenk, the mismatched buddy film follows a troubled NYPD officer who's forced to take a happy, but down-on- his-luck witness 16 blocks from the police station to 100 Centre Street, although no one wants the duo to make it.