Rare Plant Register for Huntingdonshire (VC31)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cambridge Nature Network Final Report

Cambridge Nature Network Final Report FOREWORD I’m delighted to introduce this important report. For years, now, we have known we need to ensure nature’s recovery, and for years that has been an all-too-elusive ambition. In fact, we are still overseeing nature’s decline. It’s a ship that simply must be turned around. Now we have a clear way forward. This report, building on the ambition to double nature in Cambridgeshire, tells us precisely how and where we can do it. Working from the ground up, looking at real places and the actual state of nature, it offers for the first time a tangible plan for the revitalisation of nature in the 10km around the city of Cambridge, based on what is already there and how it can be brought back to life. And there’s more. Fully integrated with the vision for nature recovery is one for the enhancement and creation of green spaces for public recreation and refreshment – vital needs, as we have come to understand fully during the covid-19 crisis. The risk with nature recovery is that in our enthusiasm we may do the wrong thing in the wrong place: plant trees on peat or valuable grassland, or put hedgerows in where the landscape should be open. This report will ensure we do the right thing in the right place. It provides a place-based analysis of where existing nature sites can be enhanced, what kind of nature-friendly farming to encourage, how to create stepping-stones to create new, linked nature networks, and how, overall, the ambition for doubling nature can be met. -

Research Framework Revised.Vp

Frontispiece: the Norfolk Rapid Coastal Zone Assessment Survey team recording timbers and ballast from the wreck of The Sheraton on Hunstanton beach, with Hunstanton cliffs and lighthouse in the background. Photo: David Robertson, copyright NAU Archaeology Research and Archaeology Revisited: a revised framework for the East of England edited by Maria Medlycott East Anglian Archaeology Occasional Paper No.24, 2011 ALGAO East of England EAST ANGLIAN ARCHAEOLOGY OCCASIONAL PAPER NO.24 Published by Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers East of England http://www.algao.org.uk/cttees/Regions Editor: David Gurney EAA Managing Editor: Jenny Glazebrook Editorial Board: Brian Ayers, Director, The Butrint Foundation Owen Bedwin, Head of Historic Environment, Essex County Council Stewart Bryant, Head of Historic Environment, Hertfordshire County Council Will Fletcher, English Heritage Kasia Gdaniec, Historic Environment, Cambridgeshire County Council David Gurney, Historic Environment Manager, Norfolk County Council Debbie Priddy, English Heritage Adrian Tindall, Archaeological Consultant Keith Wade, Archaeological Service Manager, Suffolk County Council Set in Times Roman by Jenny Glazebrook using Corel Ventura™ Printed by Henry Ling Limited, The Dorset Press © ALGAO East of England ISBN 978 0 9510695 6 1 This Research Framework was published with the aid of funding from English Heritage East Anglian Archaeology was established in 1975 by the Scole Committee for Archaeology in East Anglia. The scope of the series expanded to include all six eastern counties and responsi- bility for publication passed in 2002 to the Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers, East of England (ALGAO East). Cover illustration: The excavation of prehistoric burial monuments at Hanson’s Needingworth Quarry at Over, Cambridgeshire, by Cambridge Archaeological Unit in 2008. -

A Report on the Fourth Botanical Nomenclature Course Organized by the Botanical Survey of India at Shillong

A REPORT ON THE FOURTH BOTANICAL NOMENCLATURE COURSE ORGANIZED BY THE BOTANICAL SURVEY OF INDIA AT SHILLONG P. LAKSHMINARASIMHAN,1 N. ODYUO,2 CHAYA DEORI,2 DEEPU VIJAYAN,2 DAVID L. BIATE,2 AND KANCHI N. GANDHI3 The Botanical Survey of India (BSI) held its fourth al., 2018) and a user’s guide to the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature Course on January 27–31, 2020 Nomenclature (Turland, 2019). at BSI-Eastern Regional Centre (BSI-ERC), Shillong. The Chaya Deori (BSI-ERC) anchored the inaugural activities. course drew 66 participants from across the country, including Odyuo gave a welcome speech, followed by remarks 45 from outside BSI (Fig. 1). Ashiho A. Mao, director of BSI, from Lakshminarasimhan, Gandhi, and chief guest Mao. was the convener of the course; P. Lakshminarasimhan, ex- Rajalakshmi Prasad and Anupama Jayasimha (former joint director of BSI, and Nripemo Odyuo, head, BSI-ERC, students of Gandhi’s at National College, Bengaluru) were served as the coordinator and facilitator, respectively. Kanchi the guests of honor. Uma Shankar (North-Eastern Hill N. Gandhi served as the course director. Participants were University, Shillong) also attended the inaugural function. provided with the latest International Code of Nomenclature Gandhi began the course with a historical review of for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code; Turland et botanical nomenclature. He provided a detailed review of FIGURE 1. Fourth Botanical Nomenclature Course organized by the Botanical Survey of India at Shillong. Delegates of the course. We thank A. R. Brach (A, GH) for helpful suggestions on the text, C. M. Gallagher, and D. -

All Other Huntingdon Walks

____ ....;;.;. ,)l,i.--= --...______ /H'untingdonshire D STRICT C O U N C L ALL OTHER HUNTINGDON WALKS WALKS KEY 1111 Green walks are accessible for push chairs and wheelchairs. Unless found in the Short Walks section, walks last approximately 60 minutes. 1111 Moderate walks last 30 to 60 minutes over 2 to 3 miles. Mixture of pathways and grass tracks. May include stiles or kissing gates. Not suitable for wheelchairs or buggies. 1111 Moderate walks with the option of a shorter easier route if desired. Mixture of pathways and grass tracks. May include stiles or kissing gates. Not suitable for wheelchairs or buggies. 1111 Advanced walks last 60 to 90 minutes over 3 to 4 miles. Mixture of pathways and grass tracks. May include stiles or kissing gates. Not suitable for new walkers. wheelchairs or buggies. Advanced walks with the option of a short/moderate route if desired. Mixture of pathways and grass tracks. May include stiles or kissing gates. Not suitable for wheelchairs or buggies. Abbots Ripton Meeting Point: Village Hall Car Park, Abbots Ripton, PE28 2PF Time: 60 minutes Grade: Orange Significant hazards to be aware of: Traffic when crossing a road. Route Instructions Hazard 1. Starting at the Village hall, turn left when out of the car park following the road until it meets the main road. 2. Cross over the road to take the footpath on the left-hand side. Traffic 3. Walking up to the gates (Lord De Ramsey’s estate) they will open as you approach – if not you can walk on the right-hand side. -

Landscape Character Assessment

OUSE WASHES Landscape Character Assessment Kite aerial photography by Bill Blake Heritage Documentation THE OUSE WASHES CONTENTS 04 Introduction Annexes 05 Context Landscape character areas mapping at 06 Study area 1:25,000 08 Structure of the report Note: this is provided as a separate document 09 ‘Fen islands’ and roddons Evolution of the landscape adjacent to the Ouse Washes 010 Physical influences 020 Human influences 033 Biodiversity 035 Landscape change 040 Guidance for managing landscape change 047 Landscape character The pattern of arable fields, 048 Overview of landscape character types shelterbelts and dykes has a and landscape character areas striking geometry 052 Landscape character areas 053 i Denver 059 ii Nordelph to 10 Mile Bank 067 iii Old Croft River 076 iv. Pymoor 082 v Manea to Langwood Fen 089 vi Fen Isles 098 vii Meadland to Lower Delphs Reeds, wet meadows and wetlands at the Welney 105 viii Ouse Valley Wetlands Wildlife Trust Reserve 116 ix Ouse Washes 03 THE OUSE WASHES INTRODUCTION Introduction Context Sets the scene Objectives Purpose of the study Study area Rationale for the Landscape Partnership area boundary A unique archaeological landscape Structure of the report Kite aerial photography by Bill Blake Heritage Documentation THE OUSE WASHES INTRODUCTION Introduction Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Context Ouse Washes LP boundary Wisbech County boundary This landscape character assessment (LCA) was District boundary A Road commissioned in 2013 by Cambridgeshire ACRE Downham as part of the suite of documents required for B Road Market a Landscape Partnership (LP) Heritage Lottery Railway Nordelph Fund bid entitled ‘Ouse Washes: The Heart of River Denver the Fens.’ However, it is intended to be a stand- Water bodies alone report which describes the distinctive March Hilgay character of this part of the Fen Basin that Lincolnshire Whittlesea contains the Ouse Washes and supports the South Holland District Welney positive management of the area. -

Cambridgeshire Tydd St

C D To Long Sutton To Sutton Bridge 55 Cambridgeshire Tydd St. Mary 24 24 50 50 Foul Anchor 55 Tydd Passenger Transport Map 2011 Tydd St. Giles Gote 24 50 Newton 1 55 1 24 50 To Kings Lynn Fitton End 55 To Kings Lynn 46 Gorefield 24 010 LINCOLNSHIRE 63 308.X1 24 WHF To Holbeach Drove 390 24 390 Leverington WHF See separate map WHF WHF for service detail in this area Throckenholt 24 Wisbech Parson 24 390.WHF Drove 24 46 WHF 24 390 Bellamys Bridge 24 46 Wisbech 3 64 To Terrington 390 24. St. Mary A B Elm Emneth E 390 Murrow 3 24 308 010 60 X1 56 64 7 Friday Bridge 65 Thorney 46 380 308 X1 To Grantham X1 NORFOLK and the North 390 308 Outwell 308 Thorney X1 7 Toll Guyhirn Coldham Upwell For details of bus services To in this area see Peterborough City Council Ring’s End 60 Stamford and 7 publicity or call: 01733 747474 60 2 46 3 64 Leicester Eye www.travelchoice.org 010 2 X1 65 390 56 60.64 3.15.24.31.33.46 To 308 7 380 Three Holes Stamford 203.205.206.390.405 33 46 407.415.701.X1.X4 Chainbridge To Downham Market 33 65 65 181 X4 Peterborough 206 701 24 Lot’s Bridge Wansford 308 350 Coates See separate map Iron Bridge To Leicester for service detail Whittlesey 33 701 in this area X4 Eastrea March Christchurch 65 181 206 701 33 24 15 31 46 Tips End 203 65 F Chesterton Hampton 205 Farcet X4 350 9 405 3 31 35 010 Welney 115 To Elton 24 206 X4 407 56 Kings Lynn 430 415 7 56 Gold Hill Haddon 203.205 X8 X4 350.405 Black Horse 24.181 407.430 Yaxley 3.7.430 Wimblington Boots Drove To Oundle 430 Pondersbridge 206.X4 Morborne Bridge 129 430 56 Doddington Hundred Foot Bank 15 115 203 56 46. -

Mycologist News

MYCOLOGIST NEWS The newsletter of the British Mycological Society 2012 (4) Edited by Prof. Pieter van West and Dr Anpu Varghese 2013 BMS Council BMS Council and Committee Members 2013 President Prof. Geoffrey D. Robson Vice-President Prof. Bruce Ing President Elect Prof Nick Read Treasurer Prof. Geoff M Gadd Secretary Position vacant Publications Officer Dr. Pieter van West International Initiatives Adviser Prof. AJ Whalley Fungal Biology Research Committee representatives: Dr. Elaine Bignell; Prof Nick Read Fungal Education and Outreach Committee: Dr. Paul S. Dyer; Dr Ali Ashby Field Mycology and Conservation: Dr. Stuart Skeates, Mrs Dinah Griffin Fungal Biology Research Committee Prof. Nick Read (Chair) retiring 31.12. 2013 Dr. Elaine Bignell retiring 31.12. 2013 Dr. Mark Ramsdale retiring 31.12. 2013 Dr. Pieter van West retiring 31.12. 2013 Dr. Sue Crosthwaite retiring 31.12. 2014 Prof. Mick Tuite retiring 31.12. 2014 Dr Alex Brand retiring 31.12. 2015 Fungal Education and Outreach Committee Dr. Paul S. Dyer (Chair and FBR link) retiring 31.12. 2013 Dr. Ali Ashby retiring 31.12. 2013 Ms. Carol Hobart (FMC link) retiring 31.12. 2012 Dr. Sue Assinder retiring 31.12. 2013 Dr. Kay Yeoman retiring 31.12. 2013 Alan Williams retiring 31.12. 2014 Prof Lynne Boddy (Media Liaison) retiring 31.12. 2014 Dr. Elaine Bignell retiring 31.12. 2015 Field Mycology and Conservation Committee Dr. Stuart Skeates (Chair, website & FBR link) retiring 31.12. 2014 Prof Richard Fortey retiring 31.12. 2013 Mrs. Sheila Spence retiring 31.12. 2013 Mrs Dinah Griffin retiring 31.12. 2014 Dr. -

Picnic on the Green Primary School Trip to Shugborough ‘All’S Well That Ends Well’

Picnic on The Green Primary School trip to Shugborough ‘All’s Well That Ends Well’ AUGUST 2016 2 THE Brampton MAGAZINE In This Issue Editorial Rambling Picnic on The Green 4 Here we go again. What have we Our trip to Shugborough 5 got in store this month? Teenage Years in Brampton 7 In Memory Of Those Who Fell In We start with a report on the recent The Battle Of The Somme 9 Picnic on the Green arranged by the We Will Remember Them 9 Events Action Group. We’ve impressions of An Evening with Gervase Phinn 10 two young reporters about a trip the All’s Well That Ends Well 11 Primary School made, and the concluding Reflections on my first month 13 part of Mick Frost’s reminiscences of being a teenager in Brampton. Huntingdon Talking Newspaper 15 Your Local Councillors 16 Talking of reminiscences the new Parish Council Meeting 17 Police and Crime Commissioner Jason Pidley International Teddy Bear Ablewhite tells us about his first month’s Freefall Competition 18 experiences. On the 400th Anniversary of Croft Close 19 William Shakespeare’s death the Brampton Biodiversity Project 20 Historical Society made a trip in the rain to Mothers’ Union 24 Stratford-upon Avon to learn about the bard and his times from the place he is CFRS Bulletin 24 most associated with. The Long View 25 Messy Church Planner 25 On the Somme anniversary there is an Parish Church of St. Mary Magdalene 26 item about the First World War memorial Parish Churches in August 27 in the parish church. -

Principles of Plant Taxonomy Bot

PRINCIPLES OF PLANT TAXONOMY BOT 222 Dr. M. Ajmal Ali, PhD 1 What is Taxonomy / Systematics ? Animal group No. of species Amphibians 6,199 Birds 9,956 Fish 30,000 Mammals 5,416 Tundra Reptiles 8,240 Subtotal 59,811 Grassland Forest Insects 950,000 Molluscs 81,000 Q: Why we keep the stuffs of our home Crustaceans 40,000 at the fixed place or arrange into some Corals 2,175 kinds of system? Desert Others 130,200 Rain forest Total 1,203,375 • Every Human being is a Taxonomist Plants No. of species Mosses 15,000 Ferns and allies 13,025 Gymnosperms 980 Dicotyledons 199,350 Monocotyledons 59,300 Green Algae 3,715 Red Algae 5,956 Lichens 10,000 Mushrooms 16,000 Brown Algae 2,849 Subtotal 28,849 Total 1,589,361 • We have millions of different kind of plants, animals and microorganism. We need to scientifically identify, name and classify all the living organism. • Taxonomy / Systematics is the branch of science deals with classification of organism. 2 • Q. What is Plant Taxonomy / Plant systematics We study plants because: Plants convert Carbon dioxide gas into Every things we eat comes Plants produce oxygen. We breathe sugars through the process of directly or indirectly from oxygen. We cannot live without photosynthesis. plants. oxygen. Many chemicals produced by the Study of plants science helps to Study of plants science helps plants used as learn more about the natural Plants provide fibres for paper or fabric. to conserve endangered medicine. world plants. We have millions of different kind of plants, animals and microorganism. -

Predictive Modelling of Spatial Biodiversity Data to Support Ecological Network Mapping: a Case Study in the Fens

Predictive modelling of spatial biodiversity data to support ecological network mapping: a case study in the Fens Christopher J Panter, Paul M Dolman, Hannah L Mossman Final Report: July 2013 Supported and steered by the Fens for the Future partnership and the Environment Agency www.fensforthefuture.org.uk Published by: School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, NR4 7TJ, UK Suggested citation: Panter C.J., Dolman P.M., Mossman, H.L (2013) Predictive modelling of spatial biodiversity data to support ecological network mapping: a case study in the Fens. University of East Anglia, Norwich. ISBN: 978-0-9567812-3-9 © Copyright rests with the authors. Acknowledgements This project was supported and steered by the Fens for the Future partnership. Funding was provided by the Environment Agency (Dominic Coath). We thank all of the species recorders and natural historians, without whom this work would not be possible. Cover picture: Extract of a map showing the predicted distribution of biodiversity. Contents Executive summary .................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 5 Methodology .......................................................................................................................... 6 Biological data ................................................................................................................... -

Huntingdonshire Local Plan to 2036 Sustainability Appraisal Explanatory Note

Huntingdonshire Local Plan to 2036 Sustainability Appraisal Explanatory Note Huntingdonshire District Council | Huntingdonshire Local Plan to 2036 Sustainability Appraisal Explanatory Note 1 Contents Huntingdonshire District Council | Huntingdonshire Local Plan to 2036 Sustainability Appraisal Explanatory Note 1 Introduction 1 2 Growth target 2 3 Distribution of growth 4 Appendices 1 Call for Sites July 2017 9 2 Summary Table of Site Sustainability Appraisals 10 Introduction 1 Huntingdonshire District Council | Huntingdonshire Local Plan to 2036 Sustainability Appraisal Explanatory Note 1 Introduction 1.1 The purpose of this explanatory note is to provide clarification on the decision-making processes which informed the selection of the growth target and the distribution of growth within the Huntingdonshire Proposed Submission Local Plan to 2036. This has been prepared following the discussions which took place at the Local Plan examination hearing sessions held on 17 July 2018. 1.2 This note supplements the Final Sustainability Appraisal Report submitted for examination on 29th March 2018 which can be found at: Final Sustainability Appraisal. It draws together elements from HELAA, particularly the site specific sustainability appraisals, and the assessments of growth targets, distribution of growth, individual site appraisals and significant changes to the Local Plan during its preparation presented in the Sustainability Appraisal to provide clarification on how the overall development strategy was prepared in the light of the alternatives that were considered. 1.3 All page references quoted are from the Final Sustainability Appraisal unless otherwise stated. 1 2 Growth target Huntingdonshire District Council | Huntingdonshire Local Plan to 2036 Sustainability Appraisal Explanatory Note 2 Growth target 2.1 In 2012 three growth options were identified and published for consultation. -

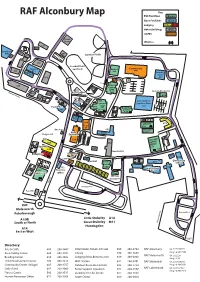

Alconbury Map Oct2015

RAF Alconbury Map Key FSS Facilities Green Base Facilities Blue Lodging Yellow Red Other Buildings Gray AAFES Orange Thrift Store Wireless 511 P 510 Fire Dept 490 566 501 567 Baseball Fields 491 Michigan California 564 548 Football Field Finance and Track Lemon Commissary 558 Kansas 516 Lot 648 TMO Recycling 561 Center 562 613 Gas 596 P Start 560 Fitness Center P GYM 595 Auto Hobby Center Base perimeter Base Theater 586 539 498 Iowa 301 626 499 592 Chapel P ODR 423rd Medical P Community Squadron Clinic Arts P Center 623 P Post Ofce Arizona and 685 Crafts Bowling 502 Alabama Daily Grind Center P 616 Texas P P Bank Arizona CU/ 582 ATM P 594 Library 675 Food 678 CT Bus Stop 652 Education Utah Base Dorm Center Playground Exchange P P TLF 584 FSS/VAT/ 628 657 A&FRC/ DEERS/ P VQ/DVQ CSS 640 699 671 Teen Center Spruce Drive Reception Shoppette 639 585 Colorado Colorado 677 682 Launderette 660 Birch Drive P Elementary 570 Mini Mall Youth Elementary P 693 School Center 6401 6402 572 6403 680 694 P 6404 High School Housing 6405 691 637 6406 691 Ofce 6407 Stukeley Inn 6408 700 Birch Drive 6409 Child 6410 CDC Development Bravo Cedar Drive Texas Elm Drive Housing Area Delta Lane Elm Drive Pass Ofce Cedar Drive Gate Foxtrot Lane Maple Drive RAF Molesworth Oak Drive Peterborough Housing Area A1(M) Little Stukeley A14 South or North Great Stukeley M11 Base perimeter Huntingdon A14 East or West India Lane Emergency Gate Directory: Arts & Crafts 685 268-3867 Information, Tickets & Travel 685 268-3704 RAF Alconbury lat: 52.3636936 Auto Hobby Center 626