The Dream of Debs by Jack London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 9, No. 8, February, 1909

The International Socialist Review A MONTHLY JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL SOCIALIST THOUGHT EDITED BY CHARLES H. KERR ASSOCIATE EDITORS: Ernest Untermann, John Spargo, Robert Rives La Monte, Max S. Hayes, William E. Bohn, Mary E. Marcy. CONTENTS FOR FEBRUARY, 1909. The Dream of Debs (Concluded) Jack L01rdon Must the Proletariat Degenerate? - Karl Kautsky Socialism for Students. IV. Thl! Class Struggle - Joseph E. Co!Jen Workers and Intellectuals in Italy Dr. Eruin Szabo The Hold Up }fan Clare11ce S. Darrou: How Tom Saved the Business Mary E. Marcy Who Constitute the Proletariat? Carl D. Thompson DEPARTMENTS Editor's Chair: Unionism and Socialism; A Choice Specimen; Local Portlanrl's Proposed Referendum. International Notes Literature and Art World of Labor News and Views Publishers' Department Subscription price, $1.00 a year, including postage, to any address in the United States, Mexico and Cuba. On account of the increased weight of the Review, we shall be obliged in future to make the subscription price to Canada $1.20 and to all other countries $1.36. All coJTespondence regardin,l!" advertising should be addressed to The Howe-simpson Company, Advertising Manager of the International Socialist Review, 140 Dear born street, Chicago. AdYt-rtising rate, $25.00 per page; half and quarter pases pro rata; less than quarter pages, 15 cents per agate line. This rate Is based on a guaranteed circulation exceeding 25,000 copies. All other business communications should be addressed to CHARLES H. KERR & COMPANY, Publishers (Co-Operative) 153 Kinzie Street, Chicago, Ill., U. S. A. Copyright, 1909, by Charles H. Kerr & Company. Entered at the I'ostoftlce at Chicago, Ill .• as St>coad Class llfatter July 27, 1900, under Act of March 3, 1879. -

Jack London Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf8q2nb2xs No online items Inventory of the Jack London Collection Processed by The Huntington Library staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Gabriela A. Montoya Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2203 Fax: (626) 449-5720 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org/huntingtonlibrary.aspx?id=554 © 1998 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Inventory of the Jack London 1 Collection Inventory of the Jack London Collection The Huntington Library San Marino, California Contact Information Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2203 Fax: (626) 449-5720 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org/huntingtonlibrary.aspx?id=554 Processed by: David Mike Hamilton; updated by Sara S. Hodson Date Completed: July 1980; updated May 1993 Encoded by: Gabriela A. Montoya © 1998 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Jack London Collection Creator: London, Jack, 1876-1916 Extent: 594 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library San Marino, California 91108 Language: English. Access Collection is open to qualified researches by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information please go to following URL. Publication Rights In order to quote from, publish, or reproduce any of the manuscripts or visual materials, researchers must obtain formal permission from the office of the Library Director. In most instances, permission is given by the Huntington as owner of the physical property rights only, and researchers must also obtain permission from the holder of the literary rights In some instances, the Huntington owns the literary rights, as well as the physical property rights. -

Qualification Work

THE MINISTRY OF PUBLIC EDUCATION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN KOKAND STATE PEDAGOGICAL INSTITUTE NAMED AFTER MUKIMIY THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PHILOLOGY GROUP IV “E” QUALIFICATION WORK Theme: “Jack London” Prepared by: M. Hatamova Checked by: D. Abdullayeva Kokand-2014 0 1 Contents: 2 Introduction .................................................................................................... p.3 Main Part: ........................................................................................................... p.9 Chapter I Jack London - his life and books 1.1 An overview …………………………………............................................. p.9 1.2 Political views............................................................................................... p.28 1.3 Working on short stories............................................................................. p.33 Chapter II I would rather be ashes than dust!.. 2.1 Novels Jack writing................................................................................. p.37 2.2 Jack London‟s „frozen‟ stories ...............................................................p.46 2.3 Major themes......................................................................................... ..p.51 Conclusion..................................................................................................... p.59 Appendix: References.............................................................. p.63 Glossary.................................................................. p.67 Introduction 3 The future -

ABSTRACT Jack London Is Not Just an Author of Dog Stories. He Is

UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA ABSTRACT Jack London is not just an author of dog stories. He is according to some literary critics, one of the greatest writers in the world. His stories are read worldwide more than any other American author, alive or dead, and he is considered by many as the American finest author. This work presents Jack London as a man who is valiant, wise, adventurous, a good worker, and a dreamer who tries to achieve his goals. He shows that poverty is not an obstacle to get them. His youth experiences inspire him to create his literary works. His work exemplifies traditional American values and captures the spirit of adventure and human interest. His contribution to literature is great. We can find in his collection of works a large list of genders like AUTORAS: María Eugenia Cabrera Espinoza Carmen Elena Soto Portuguéz 1 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA novels, short stories, non-fiction, and autobiographical memoirs. These genders contain a variety of literary styles, adventure, drama, suspense, humor, and even romance. Jack London gets the materials of his books from his own adventures; his philosophy was a product of his own experiences; his love of life was born from trips around the world and voyages across the sea. Through this work we can discover that the key of London's greatness is universality that is his work is both timely and timeless. Key Words: Life, Literature, Work, Contribution, Legacy. AUTORAS: María Eugenia Cabrera Espinoza Carmen Elena Soto Portuguéz 2 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA INDEX ACKNOWLEDGMENTS DEDICATIONS INDEX ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION CHAPTER ONE: JACK LONDON´S BIOGRAPHY 1.1 Childhood 1.2 First success 1.3 Marriage 1.4 Death CHAPTER TWO: WORKS 2.1 Short stories 2.2 Novels 2.3 Non-fiction and Autobiographical Memoirs 2.4 Drama AUTORAS: María Eugenia Cabrera Espinoza Carmen Elena Soto Portuguéz 3 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA CHAPTER THREE: ANALYSIS OF ONE OF LONDON´S WORKS 1.1 “The Call of the Wild 1.2 Characters 1.3 Plot 1.4 Setting CHAPTER FOUR: LONDON´S LEGACY 1. -

SPECIAL COLLECTIONS: Inventory

SPECIAL COLLECTIONS: Inventory UNIVERSITY LIBRARY n SONOMA STATE UNIVERSITY n library.sonoma.edu Jack London Collection Pt. 1 Box and Folder Inventory Photocopies of collection materials 1. Correspondence 2. First Appearances: Writings published in magazines 3. Movie Memorabilia (part 1) 4. Documents 5. Photographs and Artwork 6. Artifacts 7. Ephemera 8. Miscellaneous Materials Related to Jack London 9. Miscellaneous Materials Related to Carl Bernatovech Pt. 2 Box and Folder Inventory Additional materials 1. Published books: First editions and variant editions, some with inscriptions. 2. Movie Memorabilia (part 2) Series 1 – Correspondence Twenty-six pieces of correspondence are arranged alphabetically by author then sub-arranged in chronological order. The majority of the correspondence is from Jack and Charmian London to Mr. Wiget, the caretaker of their ranch in Glen Ellen, or to Ed and Ida Winship. The correspondence also includes one love letter from Jack to Charmian. Series 2 – First Appearances: Writings published in magazines Magazines often provided the first appearances of Jack London’s short stories and novels in serialized form. For example, The Call of the Wild first appeared in the Saturday Evening Post in June of 1903. It was then published later that same year by the Macmillan Company. Studying first appearances in magazines gives the researcher the opportunity to analyse textual changes that occurred over time and provides an opportunity to view the original illustrations. In several instances, Jack London specifically chose the illustrator for his stories. The collection contains two hundred and thirty-seven of Jack London’s magazine publications, both fiction and non-fiction, including many first appearances. -

Jack London Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf8q2nb2xs Online items available Jack London Papers Finding aid prepared by David Mike Hamilton and updated by Huntington Library staff. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 1980, 2015 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Jack London Papers mssJL 1-25307, etc.mssJL 1-25307, mssJLB 1-67,mssJLE 1-3525, 1 mssJLK 1-133, mssJLP 1-782, mssJLS 1-76, mssJLT 1-127 Descriptive Summary Title: Jack London Papers Dates: 1866-1977 Bulk dates: 1904-1916 Collection Number: mssJL 1-25307, etc. Collection Number: mssJL 1-25307, mssJLB 1-67,mssJLE 1-3525, mssJLK 1-133, mssJLP 1-782, mssJLS 1-76, mssJLT 1-127 Creator: London, Jack, 1876-1916 Extent: approximately 60,000 items in 622 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: The collection contains the papers of American writer Jack London (1876-1916) and includes literary manuscripts of most of London's works, extensive correspondence files, documents, photographs, ephemera, and scrapbooks. Language of Material: The records are in English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. The scrapbooks and photograph albums are too fragile for reading room use. Microfilm and digitized images are available respectively to view these items. Boxes 433 are available with curatorial approval. -

Jack London's Works by Date of Composition

Jack London's Works by Date of Composition By James Williams The following chronological listing is an aid to further research in London studies. Used with other sources it becomes a powerful means to clarify the obscurities and confusions surrounding London's writing career. The rationale for including the following titles is two-fold. First, all novels and all stories listed in Russ Kingman, "A Collector's Guide to Jack London" have been included. I chose Kingman's list rather than Woodbridge's bibliography because the former is easier to use for this purpose and is as reliable as the latter. In addition, stories, sketches, and poems appear in the following list that were not published by London but are significant because they give us a fuller idea of the nature of London's work at a particular time. This is especially true for the first years of his writing. A few explanations concerning the sources are necessary. I have been conservative in my approximations of dates that cannot be pinpointed exactly. If, for example, a story's date of composition cannot be verified, and no reliable circumstantial evidence exists, then I have simply given its date of publication. Publication dates are unreliable guides for composing dates and can be used only as the latest possible date that a given story could have been written. One may find out if the date given is a publication date simply by checking to see if the source is Woodbridge, the standard London bibliography. If the source used is JL 933-935, then the date is most likely the earliest date London sent the manuscript to a publisher. -

Fall Winter 2013 Vol. 24, No. 2-Spring Summer 2014, Vol. 25

123 The Magazine of the THE CALL Jack London Fall/Winter 2013 Vol. 24, No. 2-Spring/Summer 2014, Vol. 25, No. 1 Society IN Memory of Greg Hayes In my pitifully tattooed brain this announcement was conducive to THE WORLD OF JACK LONDON HAS LOST A FRIEND nothing “going forward” (that unnerving cliché). Instead I was propelled into By Louis Leal keenly focused backward-looking— Satchel Paige (“Don’t look back, something might be gaining on you”) Greg Hayes, retired He was president of the board would not have approved of me when JLSHP was in danger of peering into deep space ranger of Jack London State closing. With his leadership the to see how fast the steamroller was Historic Park (JLSHP), died, slow and difficult process of the rolling. Suddenly expectation surrounded by loved ones, on association taking over the opera- needed to mesh with outcome July 9, 2014 at 62 after a long tion of the park was successful perfectly. Which, face it, happens how often? struggle with cancer. He is and JLSHP was not only saved, but also became the first Califor- Anyway, long story survived by his wife Robin hopefully not short, nia State Park run by a non-profit angels immediately lined up Fautley and daughter Ni- organization. colette. Both will remember on the telephone lines His received a B.A. from outside my streaky windows him as an incredible husband UCLA and an M.A. in American replacing each crow and father. Literature from Sonoma State like reverse notes Hayes joined Jack London State University. -

Jack London Bibliography 2010-2014 2010

JACK LONDON BIBLIOGRAPHY 2010-2014 Calvin Hoovestol 2010 BOOKS Asprey, Matthew, ed. Jack London: San Francisco Stories. Preface by Rodger Jacobs. Sydney, Australia: Sydney Samizdat P, 2010. Print. Inspired by a 2009 trip to San Francisco to collect this anthology, Asprey has selected London stories set in the San Francisco Bay Area. Jacobs's 10-page preface recasts the 2003 essay “Ghost Land” as a personal meditation on Heinold's First and Last Chance Saloon, (still open in Oakland today), where young London studied, read, drank, fraternized, and wrote about his life and the people around him. Haley, James L. Wolf: The Lives of Jack London. New York: Basic Books, 2010. Print. Haley offers a self-described “guerrilla piece” of “penumbral investigation” around the “tight circle of scholars intent on vindicating London as a Great Writer” and the “establishment reactionaries” who lack an appropriate “biographer’s eye.” Haley’s tone is combative. His opinions are brusque. For example, he remarks that “(i)n one of the coats of whitewash in her biography, Charmian denied any trouble with Roscoe [Eames].” He speculates that London, who advocated strength, health, and male friendship, was bisexual or homosexual. Haley portrays London as “a poor husband and a disastrous father,” but he also presents positive elements of London’s adventurous life. Footnoting and documenting his arguments, Haley enthusiastically eschews hagiology. Hayes, Gregory W., and Matt Atkinson. Jack London’s Wolf House. Illustrated by Steven Chais. Glen Ellen, CA: Valley of the Moon Natural History Assoc., 2010. Print. Dedicated park rangers Greg Hayes and Matt Atkinson worked at the Jack London State Historic Park for a combined 44 years before writing the story of Wolf House, London’s grand but doomed Sonoma Valley home that mysteriously burned in 1913 before it was finished. -

Fine Printing Including Material from the Libraries of Allan Sommer, Robert Kinne & the Beat Collection of the Late Arthur Stockett

Sale 448 Thursday, February 24, 2011 1:00 PM Fine Literature – Fine Printing Including material from the libraries of Allan Sommer, Robert Kinne & the Beat collection of the late Arthur Stockett Auction Preview Tuesday, February 22, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wedensday, February 23-13, 9:00 am to 3:00 pm Thursday, February 24, 9:00 am to 1:00 pm Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. -

The Fiction of Jack London

1 The Fiction of Jack London: A Chronological bibliography Compiled and Annotated by DALE L.WALKER The University of Texas at El Paso Original Research and Editing by JAMES E. SISSON III Berkeley, California Updated Research and Editing by Daniel J. Wichlan Pleasant Hill, California 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 3 Introduction (Revised) 6 Key to Collections 10 Chronological Bibliography 12 Books by Jack London 48 Jack London: A Chronology 51 Appendix 54 Index 56 Selected Sources 64 3 FOREWORD TO THE NEW EDITION Through the assistance of the late Russ Kingman, the great Jack London authority and long- time friend, I made contact by correspondence with James E. Sisson III, in 1970. I had asked Russ for advice on who I could contact on questions about some of London’s hard-to-find short fiction. "Jim Sisson is the guy," said Russ. Sisson, a Berkeley, California, researcher, was very helpful from the outset and his encyclopedic knowledge of London’s work quickly resolved my questions. In subsequent correspondence I learned that Sisson felt London’s short stories were not adequately treated in Jack London: A Bibliography, compiled by Hensley Woodbridge, John London and George H. Tweney (Georgetown, CA: Talisman Press, 1966). He complained that the stories were buried among magazine articles, chapters from The Cruise of the Snark, The Road, and other nonfiction works, all lost in a welter of foreign language translations including Latvian, Finnish, Turkoman, and Ukrainian. He also claimed that many of London’s stories were missing from Woodbridge, remaining buried in obscure and long-defunct magazines, uncollected in book form. -

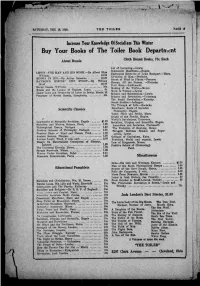

Tbvtu. OWN STORY

SATURDAY, DEC. 18, 1920. THE TOILER PAGE 15 Increase Your Knowledge Of Socialism This Winter Buy Your Books of The Toiler Book Department Cloth Bound Books, 75c Each About Russia Art of Lecturing. Lewis LENrN-T- TIE MAN AND HIS WORK.-- By Albert jgj ggggg TBvtU. OWN STORY. By William RAYMOND ROBINS' A R Niet8che. H Karl Marx, Liebknceht. RuMia, WUHmm, ' in. Soviet M;(ki of thp Wor,d.-Me- ver. Russia and the League of Nations. Lenin, , 5e ...... Jf Tolstov.-Le- wis of n Soviet Russia 25 . Labor Laws and Protection Labor Sunerstition.-Lew- to. of Russia, Humphries 10c Structure Soviet gcienee Rpvolution.-Unter- man The Social Revolution. Kautsky. Social Studies. Lafargue. The Triumph of Life. Boelsche. Scientific Classics rtS!2S B1ts 1f 8ocialist Value, Price and Profit, Marx. Origin of the Family, Engles. World's Revolutions, Untermnn. Landmarks of Scientific Socialism, Engels 1.25 Socialism, Utopian and Scientific. Engels. Socialism and Modern Science, Fern, 1.25 Anarchism and Socialism, Plecbanoff. Philosophical Essays, Dietzgen 1.50 The Kvoiution 0f Banking, Howe. 1.50 Positive Outcome of Philosophy, Dietzgen struggle Between Science and Super-Physic- Basis of Mind and Morals, Fitch, 1.25 stition Lewis. Ancient Society, Morgan 1.50 Collapae' of Capitalism, Kahn. Ancipiit Lowlv, Ward. 2 vols, each . 2.50 Evolution. Social and organic, Lewis. Essays On Materialistic Conception of History, Law of Biogenesis, Moore. Lnhrioli 1.25 p08itive School of Criminology. The Universal Kinship, Moore 18 Ferri. Savage Survivals, Moore, Woman I'nder Socialism, Rebel 2.25 Economic Determinism, Parce 1.25 Miscellaneous Debs His Life and Writings, Karsner, $150 Man or the State, Philosophical Essays 100 Educational Pamphlets Stories of the Cave People, Marcy, 1.25 Pelle the Conqueror, 2 vols.