NPEC) to Reconsider U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Außenpolitischer Bericht 2004

U2_U3.qxd 14.10.2005 11:37 Seite 1 Bundesministerium für auswärtige Angelegenheiten Minoritenplatz 8 A-1014 Wien Telefon: während der Bürozeiten an Werktagen in der Zeit von 9 bis 17 Uhr: 0 50 11 50-0 / int.: +43 50 11 50-0 für allgemeine Informationen: 0 802 426 22 (gebührenfrei; aus dem Ausland nicht wählbar) Fax: 0 50 11 59-0 / int.: +43 50 11 59-0 E-Mail: [email protected] Telegramm: AUSSENAMT WIEN Internet: http://www.bmaa.gv.at Bürgerservice: In dringenden Notfällen im Ausland ist das Bürgerservice rund um die Uhr erreichbar. Telefon: 0 50 11 50-4411 / int.: +43 50 11 50-4411 alternativ: (01) 90 115-4411 / int.: (+43-1) 90 115-4411 Fax: 0 50 11 59-4411 / int.: +43 50 11 59-4411 alternativ: (01) 904 20 16-4411 / int.: (+43-1) 904 20 16-4411 E-Mail: [email protected] Die Möglichkeiten zur Hilfeleistung an ÖsterreicherInnen im Ausland sind auf der Homepage des Bundesministeriums für auswärtige Angelegenheiten www.bmaa.gv.at unter dem Punkt „Bürgerservice“ ausführlich dargestellt. Außenpolitischer Bericht 2004 Bericht der Bundesministerin für auswärtige Angelegenheiten 1 Medieninhaber und Herausgeber: Bundesministerium für auswärtige Angelegenheiten 1014 Wien, Minoritenplatz 8 Gesamtredaktion und Koordination: Ges. MMag. Thomas Schlesinger, MSc. Mag. Elisabeth Reich Gesamtherstellung: Manz Crossmedia GmbH & Co KG, Stolberggase 26, 1051 Wien 2 VORWORT Das Jahr 2004 war für Österreich und die Europäische Union zweifellos ein historisches Jahr: Am 1. Mai traten zehn neue Mitgliedstaaten der Union bei. Mit dieser Erweiterungsrunde, der größten in der Geschichte der Europäischen Union, wurde die jahrzehntelange Spaltung Europas endgültig überwunden. -

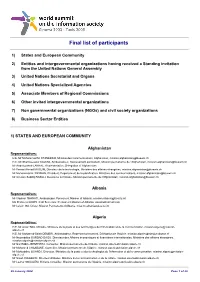

Final List of Participants

Final list of participants 1) States and European Community 2) Entities and intergovernmental organizations having received a Standing invitation from the United Nations General Assembly 3) United Nations Secretariat and Organs 4) United Nations Specialized Agencies 5) Associate Members of Regional Commissions 6) Other invited intergovernmental organizations 7) Non governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations 8) Business Sector Entities 1) STATES AND EUROPEAN COMMUNITY Afghanistan Representatives: H.E. Mr Mohammad M. STANEKZAI, Ministre des Communications, Afghanistan, [email protected] H.E. Mr Shamsuzzakir KAZEMI, Ambassadeur, Representant permanent, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Mr Abdelouaheb LAKHAL, Representative, Delegation of Afghanistan Mr Fawad Ahmad MUSLIM, Directeur de la technologie, Ministère des affaires étrangères, [email protected] Mr Mohammad H. PAYMAN, Président, Département de la planification, Ministère des communications, [email protected] Mr Ghulam Seddiq RASULI, Deuxième secrétaire, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Albania Representatives: Mr Vladimir THANATI, Ambassador, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Ms Pranvera GOXHI, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Mr Lulzim ISA, Driver, Mission Permanente d'Albanie, [email protected] Algeria Representatives: H.E. Mr Amar TOU, Ministre, Ministère de la poste et des technologies -

Iran Human Rights Documentation Center

Iran Human Rights Documentation Center The Iran Human Rights Documentation Center (IHRDC) believes that the development of an accountability movement and a culture of human rights in Iran are crucial to the long-term peace and security of the country and the Middle East region. As numerous examples have illustrated, the removal of an authoritarian regime does not necessarily lead to an improved human rights situation if institutions and civil society are weak, or if a culture of human rights and democratic governance has not been cultivated. By providing Iranians with comprehensive human rights reports, data about past and present human rights violations and information about international human rights standards, particularly the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the IHRDC programs will strengthen Iranians’ ability to demand accountability, reform public institutions, and promote transparency and respect for human rights. Encouraging a culture of human rights within Iranian society as a whole will allow political and legal reforms to have real and lasting weight. The IHRDC seeks to: Establish a comprehensive and objective historical record of the human rights situation in Iran since the 1979 revolution, and on the basis of this record, establish responsibility for patterns of human rights abuses; Make such record available in an archive that is accessible to the public for research and educational purposes; Promote accountability, respect for human rights and the rule of law in Iran; and Encourage an informed dialogue on the human rights situation in Iran among scholars and the general public in Iran and abroad. Iran Human Rights Documentation Center 129 Church Street New Haven, Connecticut 06510, USA Tel: +1-(203)-772-2218 Fax: +1-(203)-772-1782 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.iranhrdc.org Photographs: The front cover photograph is of the reflection of the main building of the Telecommunication Company of Iran. -

Downloads’ Section and an Online Shop

OCTOBER 2015 Iranian Internet Infrastructure and Policy Report A Small Media monthly report bringing you all the latest news on internet policy and online censorship direct from Iran. smallmedia.org.uk This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License Iranian Internet 2 Infrastructure and Policy Report Introduction In late October, controversy erupted when Telegram’s Russian founder Pavel Durov claimed that Iran’s ICT Ministry had requested “spying and censorship tools” from the company. When Durov refused, Telegram was blocked in Iran. As this episode demonstrates, the Iranian government has minimal control over foreign social media companies. Yet the government may have an easier time when it comes to domestic platforms. In this month’s report, we take a look at the terms and conditions that Iranian social networks require users to agree to, and how they relate to Iranian media law. We’ll also cover the dispute over Telegram filtering, renewed criticism of the Supreme Council of Cyberspace, and the announcement that Iranians can start shopping at online retailers like Amazon, Ebay, and Alibaba. Iranian Internet 3 Infrastructure and Policy Report 1 Terms and Conditions of Iranian Services Iran’s social media ecosystem features a number of copycat platforms that look suspiciously similar to their Western counterparts. Iran has its own version of Facebook, Youtube, and Instagram, and official are constantly trying to encourage Iranians to opt for the domestic platforms. Yet despite the government’s best efforts, users have been less than enamored with Iranian social networks. The founder of Facenama, an Iranian version of Facebook, announced in April 2014 that the social network had 1.2 million users, whereas culture minister Ali Jannati estimated in January 2015 that Facebook has 5.4 million Iranian users. -

Explaining the Economic Control of Iran by the IRGC

University of Central Florida STARS HIM 1990-2015 2011 Explaining the economic control of Iran by the IRGC Matthew Douglas Robin University of Central Florida Part of the Political Science Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIM 1990-2015 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Robin, Matthew Douglas, "Explaining the economic control of Iran by the IRGC" (2011). HIM 1990-2015. 1236. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/1236 EXPLANING THE ECONOMIC CONTROL OF IRAN BY THE IRGC by MATTHEW DOUGLAS ROBIN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Political Science in the College of Sciences and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2011 Thesis Chair: Dr. Houman Sadri ©2011 Matthew Douglas Robin ii ABSTRACT In 1979, Iran underwent the Islamic Revolution, which radically changed society. The Iranian Revolution Guard (IRGC) was born from the revolution and has witnessed its role in society changed over time. Many have said the IRGC has reached the apex of its power and is one of if not the dominating force in Iranian society. The most recent extension of the IRGC’s control is in the economic realm. The purpose of this research is to explain the reasoning and mechanism behind this recent gain in power. -

Der Iran Seit 1979 Bis 2008 Und Seine Beziehungen Zu Österreich“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Der Iran seit 1979 bis 2008 und seine Beziehungen zu Österreich“ Verfasserin: Azita Piran-Naderi angestrebter akademischer Grad: Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. Phil.) Wien, im Oktober 2008 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: a9402739 Studienrichtung lt. Studienplan Politikwissenschaft Betreuer: Dr. John Bunzl Der Iran seit 1979 bis 2008 und seine Beziehungen zu Österreich Vorwort Die Motivation über dieses Thema zu schreiben und vor allem zu recherchieren bestand schon seit Anbeginn meines Studiums. Als ein in Österreich geborenes Kind, eines in Österreich eingereisten persischen Ehepaars, um hier zu studieren, wurde ich mit der Wertvorstellung und den Normen der iranischen Kultur erzogen. Ich habe mich seit meiner frühesten Kindheit mit dieser Dualität, Iran-Österreich auseinandergesetzt und kann mich bis zum heutigen Tage nicht ausschließlich dem einen oder dem anderen Land zugehörig fühlen. Die Erörterung dieses Themas ist ein weiterer Schritt auf der Suche nach meiner kulturellen und weltlichen Identität, um meiner Zerrissenheit zwischen der österreichischen und iranischen Mentalität zu begegnen. Die fachliche Auseinandersetzung im Rahmen einer Diplomarbeit sollte es mir erlauben mich ‚offiziell’ und eingehend mit diesen zwei für mich als Heimatländer geltenden Staaten und deren Kohärenz zu befassen und einen bescheidenen Beitrag zum Verständnis der bilateralen Beziehungen zu leisten. Somit ist mein Zugang zu diesem Thema keine pure Außensicht, sie ist stark geprägt von eigenen Erlebnissen und Wahrnehmungen, die ich im Laufe der Zeit erfahren habe. Mit diesem Hintergrund war ich jedoch bemüht, meinen subjektiven Zugang zur Materie im Positiven zu nützen und eine ausgewogene und genuine Analyse dieses Themas zu entwickeln. An dieser Stelle möchte ich all jenen, deren Namen hier unerwähnt bleiben soll, danken, die mich über die Jahre hinweg immer wieder ermutigt haben mein Studium zu beenden. -

False Freedom Online Censorship in the Middle East and North Africa

Human Rights Watch November 2005 Volume 17, No. 10(E) False Freedom Online Censorship in the Middle East and North Africa About this Report...........................................................................................................................................1 Summary ..........................................................................................................................................................2 Regional Overview .....................................................................................................................................3 Recommendations......................................................................................................................................7 Note on Methodology ...............................................................................................................................8 Legal Standards Pertaining to Online Freedom of Expression.............................................................10 Right to Freedom of Expression and Exchange of Information......................................................10 Right to Privacy ........................................................................................................................................14 Anonymity and Encryption ....................................................................................................................15 Assigning Liability for Online Content.................................................................................................16