Neuehouse from June 2013 to Jan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Healon Project (1971-77)

The Magic Molecule that has improved the lives of millions Börje Svensson Copyright The publisher will keep this document online on the Internet – or its possible replacement – for a considerable time from the date of publication barring exceptional circumstances. The online availability of the document implies permanent permission for anyone to read, to download, or to print out single copies for his/her own use and to use it unchanged for non- commercial research and educational purposes. Subsequent transfers of copyright cannot revoke this permission. All other uses of the document are conditional upon the consent of the copyright owner. The publisher has taken technical and administrative measures to assure authenticity, security and accessibility. According to intellectual property law, the author has the right to be mentioned when his/her work is accessed as described above and to be protected against infringement. For additional information about Linköping University Electronic Press and its procedures for publication and for assurance of document integrity, please refer to its www home page: http://www.ep.liu.se/. Linköping University Electronic Press Linköping, Sweden, 2015 ISBN: 978-91-7519-076-1 © Börje Svensson, 2015 [email protected] Photo at the front page: “White leghorn rooster” by Sándor Szirmai. Gift from the artist to Endre Balazs (May 22, 1962) 2 Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................. 5 Part I: The early -

Lifestyle Features Monday, August 24, 2020

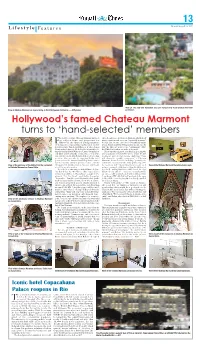

13 Lifestyle Features Monday, August 24, 2020 View of the pool and bungalow area and Sunset strip from Chateau Marmont View of Chateau Marmont on Sunset Strip, in West Hollywood, California. — AFP photos penthouse. or nearly a century Chateau Marmont has been just a decade ago. At Chateau Marmont, shielded-off an adopted home and playground for private quarters will serve an “essentially nomadic” FHollywood’s elite, discreetly hosting sophisticat- wealthy and creative elite tired of traditional luxury ed Golden Age icons and raucous Brat Pack celebri- hotels, Balazs said. But Balazs insists media reports ties. Etched into Tinseltown folklore, it is where James that “the Chateau” is set to ape “exclusionary clubs” Dean crashed director Nicholas Ray’s bungalow to like White’s in London, are wide of the mark. bag the lead in “Rebel Without a Cause,” Jean Harlow Those reports triggered a backlash in Los Angeles and Clark Gable allegedly conducted a torrid affair, among stargazers fearful they will no longer be able and comedy legend John Belushi died of a tragic drug to dine across from their favorite celebrities. “There overdose. More recently, the imposing Gothic hotel will always be a public component” to Chateau perched above the famous Sunset Strip has become a Marmont, Balazs told AFP, including “probably the hub for swanky showbiz parties, from Leonardo restaurant... and then maybe some public aspect to View of the entrance of the lobby from the restaurant DiCaprio’s 21st birthday bash to Beyonce and Jay-Z’s the rooms as well.” “Something that’s become as, if View of the Chateau Marmont Bungalow living room. -

In the Spirit

GLOBAL GOING LUXE REACH THE BELLEVUE COLLECTION AS PROFITS AT PLOTS A $1.2 BILLION ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA RISE EXPANSION TO RAISE THE 13 PERCENT, THE BRAND LUXURY QUOTIENT IN SEATTLE. PLANS MORE RETAIL EXPANSION. PAGE 2 PAGE 12 BANGLADESH TRAGEDY Retailers, Groups Vow Compensation By MAYU SAINI WHO IS GOING TO PAY and how much? That is among the questions being asked as the death toll from the collapse of the apparel factory building in Savar, near Dhaka, Bangladesh, rose to 430 on Thursday, with more than 520 injured, out of which 100 amputations have been estimated. FRIDAY, MAY 3, 2013 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY ■ $3.00 The rest of the rescued workers will also need WWD new jobs, as well as immediate payments. Hundreds of workers are still missing, and eight days after the eight-story building collapsed, bodies are still being recovered from the debris. The building, Rana Plaza, housed fi ve garment fac- tories, with more than 3,000 workers in the building at the time of the collapse. The incident is being de- scribed by authorities as the worst industrial accident in the garment industry in Bangladesh and the world. “The total compensation fi gure is likely to be over $30 million in addition to the cost of emergency treat- ment,” the Clean Clothes Campaign said last week, when the death toll was known to be 300. In the But a presentation by the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers & Exports Association earlier this week noted a vastly different number, stating that the amount needed for “compensation, rehabilitation and long-term treatment was estimated at $12 million.” The organization also noted that an amount of 125 Spirit million Bangladesh taka, or $1.6 million at current ex- change rates, had already been spent on rescue activi- The Estée Lauder brand will ties and treatment. -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK : in Re: : Chapter 11 : 1141 REALTY OWNER LLC, Et Al., : Case No

18-12341-smb Doc 36 Filed 09/05/18 Entered 09/05/18 10:47:47 Main Document Pg 1 of 217 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK : In re: : Chapter 11 : 1141 REALTY OWNER LLC, et al., : Case No. 18-12341 (SMB) : : Jointly Administered Debtors. : : DECLARATION OF EDWARD R. ESCHMANN IN FURTHER SUPPORT OF DEBTORS’ MOTION FOR ENTRY OF INTERIM AND FINAL ORDERS AUTHORIZING THE DEBTORS TO OBTAIN POST-PETITION, PRIMING, SENIOR SECURED, SUPERPRIORITY FINANCING PURSUANT TO 11 U.S.C. §§ 105, 362, 364(c) AND 364(d), BANKRUPTCY RULE 4001(c) AND LOCAL BANKRUPTCY RULE 4001-2 Edward R. Eschmann, MAI, declares as follows pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1746: 1. I am a Director of the Valuation and Advisory Hospitality and Gaming Group of CBRE, Inc. (“CBRE”) in New York City, where I have been employed since 2000. 2. I have more than thirty-four (34) years’ experience of valuation and consulting experience throughout the United States, Puerto Rico and the Americas. I am a designated Member of the Appraisal Institute and Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors and a Certified General Real Estate Appraiser in the states of New York and New Jersey and have held licenses in other jurisdictions including Connecticut, Vermont, Illinois, Washington, DC and Pennsylvania. I have a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. 3. Since 2006, I have specialized in the hospitality asset class and have been the director of the Tri-State Hospitality Group of CBRE in New York City covering the New York, New Jersey and Connecticut region. -

2007 Manhattan Hotel Market Overview Page 1 of 28

HVS Hospitality Services : 2007 Manhattan Hotel Market Overview Page 1 of 28 Manhattan Hotel Market Overview HVS Hospitality Services, in cooperation with New York University's Preston Robert Tisch Center for Hospitality, Tourism, and Sports Management, is pleased to present the tenth annual Manhattan Hotel Market Overview. A slight uptick in Manhattan’s occupancy level in 2006 led to a record high of 85.0%. Despite a virtually stable occupancy, the Manhattan lodging market registered a 13.4% increase in RevPAR compared to 2005, continuing its impressive performance. The market’s RevPAR gain was supported by double-digit growth in average rate each month of the year, with the exception of December, causing year-end 2006 average rate to exceed the 2005 level by 13.2%. The high rates registered by the Manhattan lodging market were caused primarily by continued strong demand levels in 2006, allowing hotel operators to be more selective with lower-rated demand and increasingly boost rates, thereby accommodating greater numbers of higher-rated travelers. We note that the market’s overall occupancy level of 85.0% in 2006 highlights the underlying strength of the Manhattan market, which continued to operate at near-maximum-capacity levels. Because of a further decline in supply in 2006, the market continued to experience many sell-out nights, causing a significant amount of demand to remain unaccommodated. Given the larger-than-ever construction pipeline in Manhattan, a substantial portion of previously unaccommodated demand is expected to be accommodated in the future. Manhattan’s marketwide occupancy and average rate both achieved new record levels in 2006, and we expect the positive trend to continue in 2007. -

The 100 Most Powerful People in New York Real Estate

NEW YORK, THE REAL ESTATE Jerry Speyer Michael Bloomberg Stephen Ross Marc Holliday Amanda Burden Craig New- mark Lloyd Blankfein Bruce Ratner Douglas Durst Lee Bollinger Michael Alfano James Dimon David Paterson Mort Zuckerman Edward Egan Christine Quinn Arthur Zecken- dorf Miki Naftali Sheldon Solow Josef Ackermann Daniel Boyle Sheldon Silver Steve Roth Danny Meyer Dolly Lenz Robert De Niro Howard Rubinstein Leonard Litwin Robert LiMandri Howard Lorber Steven Spinola Gary Barnett Bill Rudin Ben Bernanke Dar- cy Stacom Stephen Siegel Pam Liebman Donald Trump Billy Macklowe Shaun Dono- van Tino Hernandez Kent Swig James Cooper Robert Tierney Ian Schrager Lee Sand- er Hall Willkie Dottie Herman Barry Gosin David Jackson Frank Gehry Albert Behler Joseph Moinian Charles Schumer Jonathan Mechanic Larry Silverstein Adrian Benepe Charles Stevenson Jr. Michael Fascitelli Frank Bruni Avi Schick Andre Balazs Marc Jacobs Richard LeFrak Chris Ward Lloyd Goldman Bruce Mosler Robert Ivanhoe Rob Speyer Ed Ott Peter Riguardi Scott Latham Veronica Hackett Robert Futterman Bill Goss Dennis DeQuatro Norman Oder David Childs James Abadie Richard Lipsky Paul del Nunzio Thomas Friedan Jesse Masyr Tom Colicchio Nicolai Ourouso! Marvin Markus Jonathan Miller Andrew Berman Richard Brodsky Lockhart Steele David Levinson Joseph Sitt Joe Chan Melissa Cohn Steve Cuozzo Sam Chang David Yassky Michael Shvo 100The 100 Most Powerful People in New York Real Estate Bloomberg, Trump, Ratner, De Niro, the Guy Behind Craigslist! They’re All Among Our 100 Most Powerful People in New York Real Estate ower. Webster’s Dictionary defines power as booster; No. 15 Edward Egan, the Catholic archbish- Governor David Paterson (No. -

Daylight & Architecture

LUX E DAYLIGHT & DAYLIGHT ARCHITECTURE BY MAGAZINE V WINTER 2008 ISSUE 10 RE-NEW 10 EURO WINTER 2008 ISSUE 10 RE-NEW 10 EURO DAYLIGHT & ArCHITECTURE MAGAZine BY VELUX Cities are like living organisms. They remain alive by continually renewing themselves. E Just as the human body’s lifespan exceeds that of its individual cells, a town gener- VELUX ally outlives its individual houses defensive walls and factories. Buildings age over time. They become unusable or no longer meet increasing expectations about com- EDITORIAL fort and space. Sometimes they are simply not impressive enough for new users or functions. These circumstances make the desire for something new only too under- standable. But there are good reasons for not acceding to calls for renewal invariably and unthinkingly. RE-NEW Renovating an old building uses up to two thirds less material than an equiva- lent new building – saving the equivalent amount of energy for producing and trans- porting materials, as Thomas Lemken writes in his article for Daylight&Architecture. Many old buildings additionally possess unrivalled construction qualities – whether a “bonus” in terms of room height and width or details and decorations in the work- manship no longer found in new buildings. Often, however, these aesthetic qualities are hidden, and it takes the work of an architect to bring them to light. In his article “More space, more light” in this issue, Hubertus Adam describes how this can hap- pen. However, existing buildings in our cities and villages also represent an unparal- leled challenge. Badly insulated old buildings are among humanity’s greatest energy wasters. -

Print Untitled (24 Pages)

SYDELL GROUP LTD. Andrew Zobler Sydell Group 2006-Present Founder and ChiefExecutive Officer The Sydell Group is a New York based owner and developer of lifestyle oriented hotels. Sydell currently controls two ventures in partnership with the Yucaipa companies. The first venture targets urban lifestyle oriented hotel properties with a strategy to acquire and develop hotels with individualized brand, design and management. The mandate of the second venture is to develop and operate premium youth hostels in major U.S. cities. Existing Projects: • NoMad Hotel, New York o Converted a 133,000 SF landmark office building into a 168-room luxury boutique hotel. The NoMad restaurant is operated by James Beard-Best Chef in America, Daniel Humm, and recently earned three-stars from the New York Times. • Ace Hotel, New York o This 180,000 SF building, which is named on the historic register, was converted to a 275-roorri hotel and was recently touted as "Best Boutique Design Hotel" by Interior Design magazine. • Ace Hotel, Palm Springs o 180-room renovation which is perhaps most well-known for its installation of Stan Bitter's work, which helped to transform the tired former Howard Johnson into a building with striking, original handcrafted detail. • The Saguaro, Old Town Scottsdale o Renovated and re-branded the former Hotel Theodore into a 195-room lifestyle hotel operated by Joie de Vivre with food & beverage offerings by James Beard award winner Jose Garces. • The Saguaro, Palm Springs o Renovated and re-branded a former Holiday Inn into a 245-room lifestyle hotel operated by Joie de Vivre with food & beverage offerings by James Beard award winner Jose Garces. -

Open PDF ... AIA-New-York-Chapter

7/12/2014 AIA New York Chapter : Calendar Search... » The Center for Architecture 536 LaGuardia Place Boat Tours Calendar Visit Education Exhibitions Support Public Programs Watch & Listen Program Partners Space Rental NY, NY 10012 (212) 683-0023 [email protected] Gallery Hours Mon-Fri: 9am to 8pm Sat: 11am to 5pm Office Hours Mon 07.14.2014 Mon-Fri: 9am to 5pm Keep in touch AIA CES 2.5 LU Subscribe now When: 6:30 PM - 9:00 PM MONDAY, JULY 14 Where: At The Center You RSVPed YES on: [Jul 12, 2014 10.31 am] ADD A GUEST export vCalendar The AIANY Global Dialogues Committee has dedicated this year to “(dis)Covered Identities.” The theme aims to explore ways by which cultures, cities, and voices define or refine their identities through a global exchange of ideas and conversations covering multiple topics, perspectives and trends of our time. "Viral Voices" will specifically explore the impact of social media, technology, and device culture on our design process and the way we practice. How do we shape a global conversation? Greg Lindsay, contributing writer for Fast Company and co-author of Aerotropolis with David Basulto and David Assael of ArchDaily will come together for a lecture discussing the relationships between social media and the profession. Following the lecture, Robyn Peterson from Mashable, Jaime Derringer from Design Milk, Diana Jou from the The Wall Street Journal, Rafi Segal from MIT Architecture / Architect/Blogger, Mark Collins from The Morpholio Project | The GSAPP CloudLab, and Kyle May from Clog will join the speakers for a panel discussion. -

TEN SPEED PRESS Food + Drink FORTHCOMING FALL 2015 TITLES

SPRING + SUMMER 2016 TEN SPEED PRESS food + drink FORTHCOMING FALL 2015 TITLES 4 5 “No chef captures the flavors of the moment COPY CATALOG better than Yotam Ottolenghi.” —Bon Appétit OCTOBER “Ottolenghi is a genius with vegetables—it’s possible that no other chef has devised so many clever ways CATALOG COPY CATALOG to cook them.” —Food & Wine NOPI: THE COOKBOOK YOTAM OTTOLENGHI AND RAMAEL SCULLY ISBN: 978-1-60774-623-2 eBook ISBN: 978-1-60774-624-9 “Near & Far is a delicious paean to the culinary glories SEPTEMBER of world travel, and the grounding comfort found in returning to one’s own home kitchen. Heidi Swanson has married her keen traveler’s eye to her devoted home cook’s soul, and created a quietly sumptuous masterpiece rooted in place that stands alongside the work of Pico Iyer and Yotam Ottolenghi for sheer, mouthwatering breadth. This book will never leave my kitchen.” —Elissa Altman, author of Poor Man’s Feast NEAR & FAR Recipes Inspired by Home and Travel HEIDI SWANSON ISBN: 978-1-60774-549-5 eBook ISBN: 978-1-60774-550-1 HOME COOKED 100 Essential Recipes for a New Way to Cook ANYA FERNALD WITH JESSICA BATTILANA A recipe-driven guide for stocking your pantry with homemade base ingredients that can be used to 3 transform easy weeknight meals, by the cofounder MARCH of the Belcampo Meat Co. Anya Fernald’s style of cooking is rustic and simple, shaped by her years of experience working on farms, living in Italy, and running Slow Food Nation—but it is also sophisticated and brilliant. -

2012 Employment Report Career Management Center Visit the Career Management Center Online At

2012 Employment Report CAREER MANAGEMENT CENTER Visit the Career Management Center online at: www.gsb.columbia.edu/recruiters. Post positions online at: www.gsb.columbia.edu/jobpost. C Columbia Business School | www.gsb.columbia.edu/recruiters RECRUITING AT COLUMBIA BUSINESS SCHOOL Columbia Business School students continue to demonstrate their remarkable ability to take theory learned in the classroom and apply it to real-life business challenges—a vital skill in today’s dynamic and global business environment. Their uncanny business acumen and innovative approach to problem solving is truly remarkable, and employers consistently report being impressed with Columbia Business School graduates’ decision-making abilities and leadership skills. Through a constantly evolving curriculum, the School fosters a team-oriented work ethic and an entrepreneurial mindset that makes creating and capturing opportunity instinctual. The core curriculum and wide variety of elective classes at Columbia provide an opportunity to examine business challenges from multiple perspectives by studying integrated cases. The School’s extraordinary network of alumni, global business partners, and faculty members, along with its seamless integration with New York City, distinguishes Columbia Business School among its peers. The Career Management Center (CMC) works with hiring organizations across the public, private, and nonprofit sectors, internationally and domestically, to develop effective and efficient recruiting strategies. Recruiters can get to know the School’s talented students in a variety of ways, including through prerecruiting events, interviews, on-campus job fairs, and educational presentations with student clubs. Companies can collaborate with the CMC to identify candidates on an as-needed basis through job postings, résumé collections, and the online résumé database. -

2015 Benefit at Christie's

2015 BENEFIT AT CHRISTIE’S TIBET HOUSE US Tibet House US is a non-profit 501(c)(3) that was founded in 1987 at the request of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, who stated his wish for a long-term cultural institution to ensure the survival of the unique Tibetan civilization. In 1998, Tibet House US moved to a 7,000 square foot permanent home with an exhibition gallery on 15th Street, just west of Fifth Avenue in New York City. This cultural center is a museum, that includes a gallery, lending library, shop, and offices. At the heart of Tibet House US is the Lhakang Shrine Room, designed and created by Tibetan artists working with traditional methods and materials. TIBET HOUSE US IS DEDICATED TO 1) Presenting to the West, Tibet’s ancient traditions of art and culture, by developing national and international traveling exhibitions, publications, and media productions. 2) Preserving and restoring Tibet’s unique cultural and spiritual heritage through developing an outstanding collection of Tibetan art. 3) Establishing an archive of rare photographs and a research library; and providing support to conservation activities inside outside of Tibet. 4) Sharing with the world Tibet’s profound systems of spiritual philosophy and mind sciences, as well as its arts of human development, intercultural dialogue, nonviolence, and peacemaking, by means of innovative programs in cooperation with like-minded educational cultural institutions. THIS YEAR WE HAVE PLEDGED TO GIVE A PORTION OF THE PROCEEDS TO The proceeds from our auctions are a major source of support for Tibet House US’s diverse programs.