33794148.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scissors Force (1940)

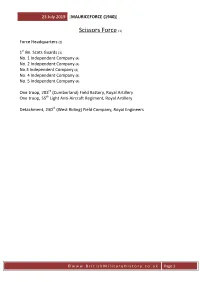

23 July 2019 [MAURICEFORCE (1940)] Scissors Force (1) Force Headquarters (2) st 1 Bn. Scots Guards (3) No. 1 Independent Company (4) No. 2 Independent Company (4) No.3 Independent Company (4) No. 4 Independent Company (4) No. 5 Independent Company (4) One troop, 203rd (Cumberland) Field Battery, Royal Artillery One troop, 55th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery Detachment, 230th (West Riding) Field Company, Royal Engineers ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Page 1 23 July 2019 [MAURICEFORCE (1940)] NOTES: 1. Scissors Force was formed in early May 1940 under the command of Colonel Colin McVean GUBBINS. The role of this force was to form a base in the Bodo, Mo and Mosjoen area to the south of Narvik and to block and delay the German advance from the south. 2. The Force Headquarters was formed from the staff of the 61st Infantry Division on 15 April 1940. 3. The 1st Bn. Scots Guards was part of the 24th Infantry Brigade (Guards) which was sent to assist in blocking the road at Mo. 4. These companies were formed with volunteers from the Territorial Army divisions then stationed in the United Kingdom. They were: Ø No. 1 Independent Company – Formed by the 52nd (Lowland) Division; Ø No. 2 Independent Company – Formed by the 53rd (Welsh) Division; Ø No. 3 Independent Company – Formed by the 54th (East Anglian) Division; Ø No. 4 Independent Company – Formed by the 55th (West Lancashire) Division; Ø No. 5 Independent Company – Formed by the 56th (London) Division; Each company comprised five officers and about two-hundred and seventy men organised into three platoons, each consisting of three sections. -

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II ORREST LEE “WOODY” VOSLER of Lyndonville, Quick Write New York, was a radio operator and gunner during F World War ll. He was the second enlisted member of the Army Air Forces to receive the Medal of Honor. Staff Sergeant Vosler was assigned to a bomb group Time and time again we read about heroic acts based in England. On 20 December 1943, fl ying on his accomplished by military fourth combat mission over Bremen, Germany, Vosler’s servicemen and women B-17 was hit by anti-aircraft fi re, severely damaging it during wartime. After reading the story about and forcing it out of formation. Staff Sergeant Vosler, name Vosler was severely wounded in his legs and thighs three things he did to help his crew survive, which by a mortar shell exploding in the radio compartment. earned him the Medal With the tail end of the aircraft destroyed and the tail of Honor. gunner wounded in critical condition, Vosler stepped up and manned the guns. Without a man on the rear guns, the aircraft would have been defenseless against German fi ghters attacking from that direction. Learn About While providing cover fi re from the tail gun, Vosler was • the development of struck in the chest and face. Metal shrapnel was lodged bombers during the war into both of his eyes, impairing his vision. Able only to • the development of see indistinct shapes and blurs, Vosler never left his post fi ghters during the war and continued to fi re. -

DESERT KNIGHTS the Birth and Early History Of

DESERT KNIGHTS The birth and early history of the SAS by Stephen Gallagher 2x90’ Part One Dr3 Gallagher/DESERT KNIGHTS1/1 1. EXT. KEIR HOUSE, SCOTLAND. NIGHT. We see a large, white country house in formal grounds, lights blazing from the ground floor windows. We can hear a faint buzz of dinner conversation. Over the building we super: KEIR HOUSE, SCOTLAND 2. INT. KEIR HOUSE DINING ROOM. NIGHT. A formal dinner party in full swing, sometime around the late 1920s. The women are in gowns and many of the men are in kilts and medals. 3. INT. KEIR HOUSE UPPER FLOOR. NIGHT. An empty, unlit corridor. Not lavish, but functional. A BAR OF LIGHT showing under a door. It goes out. PAN UP as the door opens a crack and DAVID checks the corridor before emerging. He's a dark-haired boy of about 12, with a dressing-gown over his pyjamas. 4. INT. KEIR HOUSE HALLWAY. NIGHT. Up at the top of the stairs, DAVID's head cautiously pokes into view. HIS POV down on the dining room doors as the butler goes in and closes them after... from the sound that's coming out they seem to be making speeches, and there's a burst of applause. Warily, he makes his way down. At the foot of the stairs, he tiptoes past the dining room. But just as it looks as if he's in the clear, he hears someone coming. He dives into the nearest cover just as... ALICE THE COOK emerges through a door from the kitchens with one of the MAIDS behind her. -

Stag Season Review 2012 Scottish Stag Review Tony Jackson High-Quality Deer and Good Weather Made the 2012 Season the Best in Several Years

ADMG – Knight Frank 2012 Stag Season Review ADMG - Knight Frank 2012 Stag Season Review 1 Aberdeenshire The reports received for 2012, despite the weather, highlight the season as one of the best in recent 2 Angus 3 Argyll years. If the beasts are in good fettle that's a good thing - without that then the whole sector has 4 Arran and Bute no foundation. 5 Caithness 6 Dunbartonshire 7 Inverness-shire While we have read in the media about a very few areas where deer numbers still require some 8 Perthshire adjustment, or where different estates or interests within the same Deer Management Group find 9 Ross-shire/Isle of Lewis it hard to agree a compromise regarding the way forward, on the ground there appear to be fewer 10 Sutherland problems and a significant move towards consensus management. We are sure that this is as a up the shot Setting Kingie, 11 Wigtownshire consequence of the Wildlife and Natural Environment Scotland Act that placed a duty on all those with deer on their ground to manage them sustainably whilst continuing to allow them to do so under the voluntary principle. 5 9 10 With the Act came the Code of Deer Management, and an ongoing campaign to improve general competence levels of those who shoot deer. This too is moving in the right direction; the standard of DSC Level 1 was agreed as the benchmark, although it is hoped that many deer managers and 9 stalkers will aim higher, and figures suggest that uptake is good ahead of a review by Government in 2014. -

Reflections and 1Rememb Irancees

DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A Approved for Public Release Distribution IJnlimiter' The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II REFLECTIONS AND 1REMEMB IRANCEES Veterans of die United States Army Air Forces Reminisce about World War II Edited by William T. Y'Blood, Jacob Neufeld, and Mary Lee Jefferson •9.RCEAIR ueulm PROGRAM 2000 20050429 011 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved I OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of Information Is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 2000 na/ 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER Reflections and Rememberances: Veterans of the US Army Air Forces n/a Reminisce about WWII 5b. GRANT NUMBER n/a 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER n/a 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER Y'Blood, William T.; Neufeld, Jacob; and Jefferson, Mary Lee, editors. -

USAMHI Special Forces

U.S. Army Military History Institute Special Operations 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 15 Jun 2012 FOREIGN SPECIAL FORCES A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources CONTENTS Soviet.....p.1 British.....p.2 Other…..p.3 SOVIET SPECIAL FORCES Adams, James. Secret Armies: Inside the American, Soviet and European Special Forces. NY: Atlantic Monthly, 1988. 440 p. UA15.5.A33. Amundsen, Kirsten, et. al. Inside Spetsnaz: Soviet Special Operations: A Critical Analysis. Novato, CA: Presidio, 1990. 308 p. UZ776.S64.I57. Boyd, Robert S. "Spetznaz: Soviet Innovation in Special Forces." Air University Review (Nov/Dec 1986): pp. 63-69. Per. Collins, John M. Green Berets, Seals and Spetznaz: U.S. and Soviet Special Military Operations. Wash, DC: Pergamon-Brassey's, 1987. 174 p. UA15.5.C64. Gebhardt, James F. Soviet Naval Special Purpose Forces: Origins and Operations in World War II. Ft Leavenworth: SASO, 1989. 41 p. D779.R9.G42. _____. Soviet Special Purpose Forces: An Annotated Bibliography. Ft. Leavenworth, KS: SASO, 1990. 23 p. Z672.4S73.G42. Kohler, David R. "Spetznaz (Soviet Special Purpose Forces)." US Naval Institute Proceedings (Aug 87): pp. 46-55. Per. Resistance Factors and Special Forces Areas, North European Russia…. Wash, DC: Asst Chief of Staff, Intell, 1957. 387 p. DK54.R47. Suvorov, Viktor. Spetsnaz: The Inside Story of the Soviet Special Forces. NY: Pocketbooks, 1990. 244 p. UA776.S64.S8813. Zaloga, Steve. Inside the Blue Berets: A Combat History of Soviet and Russian Airborne Forces, 1930- 1995. Novato, CA: Presidio, 1995. 339 p. UZ776S64.Z35. _____. Soviet Bloc Elite Forces. London: Osprey, 1985. -

Lochailort (Potentially Vulnerable Area 01/22)

Lochailort (Potentially Vulnerable Area 01/22) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Highland and Argyll The Highland Council Ardnamurchan coastal Summary of flooding impacts Summary of flooding impactsSummary At risk of flooding • <10 residential properties • <10 non-residential properties • £14,000 Annual Average Damages (damages by flood source shown left) Summary of objectives to manage flooding Objectives have been set by SEPA and agreed with flood risk management authorities. These are the aims for managing local flood risk. The objectives have been grouped in three main ways: by reducing risk, avoiding increasing risk or accepting risk by maintaining current levels of management. Objectives Many organisations, such as Scottish Water and energy companies, actively maintain and manage their own assets including their risk from flooding. Where known, these actions are described here. Scottish Natural Heritage and Historic Environment Scotland work with site owners to manage flooding where appropriate at designated environmental and/or cultural heritage sites. These actions are not detailed further in the Flood Risk Management Strategies. Summary of actions to manage flooding The actions below have been selected to manage flood risk. Flood Natural flood New flood Community Property level Site protection protection management warning flood action protection plans scheme/works works groups scheme Actions Flood Natural flood Maintain flood Awareness Surface water Emergency protection management warning raising plan/study -

The Quandary of Allied Logistics from D-Day to the Rhine

THE QUANDARY OF ALLIED LOGISTICS FROM D-DAY TO THE RHINE By Parker Andrew Roberson November, 2018 Director: Dr. Wade G. Dudley Program in American History, Department of History This thesis analyzes the Allied campaign in Europe from the D-Day landings to the crossing of the Rhine to argue that, had American and British forces given the port of Antwerp priority over Operation Market Garden, the war may have ended sooner. This study analyzes the logistical system and the strategic decisions of the Allied forces in order to explore the possibility of a shortened European campaign. Three overall ideas are covered: logistics and the broad-front strategy, the importance of ports to military campaigns, and the consequences of the decisions of the Allied commanders at Antwerp. The analysis of these points will enforce the theory that, had Antwerp been given priority, the war in Europe may have ended sooner. THE QUANDARY OF ALLIED LOGISTICS FROM D-DAY TO THE RHINE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of History East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History By Parker Andrew Roberson November, 2018 © Parker Roberson, 2018 THE QUANDARY OF ALLIED LOGISTICS FROM D-DAY TO THE RHINE By Parker Andrew Roberson APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF THESIS: Dr. Wade G. Dudley, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER: Dr. Gerald J. Prokopowicz, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER: Dr. Michael T. Bennett, Ph.D. CHAIR OF THE DEP ARTMENT OF HISTORY: Dr. Christopher Oakley, Ph.D. DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL: Dr. Paul J. -

Canadian Airmen Lost in Wwii by Date 1943

CANADA'S AIR WAR 1945 updated 21/04/08 January 1945 424 Sqn. and 433 Sqn. begin to re-equip with Lancaster B.I & B.III aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). 443 Sqn. begins to re-equip with Spitfire XIV and XIVe aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). Helicopter Training School established in England on Sikorsky Hoverfly I helicopters. One of these aircraft is transferred to the RCAF. An additional 16 PLUTO fuel pipelines are laid under the English Channel to points in France (Oxford). Japanese airstrip at Sandakan, Borneo, is put out of action by Allied bombing. Built with forced labour by some 3,600 Indonesian civilians and 2,400 Australian and British PoWs captured at Singapore (of which only some 1,900 were still alive at this time). It is decided to abandon the airfield. Between January and March the prisoners are force marched in groups to a new location 160 miles away, but most cannot complete the journey due to disease and malnutrition, and are killed by their guards. Only 6 Australian servicemen are found alive from this group at the end of the war, having escaped from the column, and only 3 of these survived to testify against their guards. All the remaining enlisted RAF prisoners of 205 Sqn., captured at Singapore and Indonesia, died in these death marches (Jardine, wikipedia). On the Russian front Soviet and Allied air forces (French, Czechoslovakian, Polish, etc, units flying under Soviet command) on their front with Germany total over 16,000 fighters, bombers, dive bombers and ground attack aircraft (Passingham & Klepacki). During January #2 Flying Instructor School, Pearce, Alberta, closes (http://www.bombercrew.com/BCATP.htm). -

EVELYN WAUGH NEWSLETTER and STUDIES Volume 27, Number 3 Winter 1993

EVELYN WAUGH NEWSLETTER AND STUDIES Volume 27, Number 3 Winter 1993 BARD IA MARTIN STANNARD'S MILITARY MUDDLE By Donat Gallagher (James Cook University, Australia) When reading Martin Stannard's No Abiding City [entitled Evelyn Waugh, The Later Years in the USA], for review, I was struck by what seemed an exceptionally large number of factual errors, unsupported claims, imputations of motive, overstatements and misreadings. The inaccuracy seemed so pervasive as to undermine the book's value as a work of record. In order to test this impression, I decided to examine a short neutral passage that would serve as a fair sample. The passage chosen for scrutiny had to be brief, and about an easily researched subject. The subject also had to be incapable of having stirred the prejudices of the biographer or the reviewer, or of awakening those of the readers of the book or review. Pages 28-31 of No Abiding City were selected because they dealt with a very minor military operation, viz. a Commando raid on Bardia, and with a humdrum article Waugh wrote about it. No issue of class, religion, politics, literary theory or internal military squabbling arises. Nor does the spectre of professional rivalry, for no one, I imagine, seeks the bubble reputation in a war of words about Bardia. The three pages narrate the events of the raid, using information drawn from Waugh's article and diaries. In addition, criticisms are made of Waugh on the basis of real and purported discrepancies between the article and the diaries. Little is said about the genesis of the article or about the administrative difficulties attending its publication. -

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1. Donald Macintyre, Narvik (London: Evans, 1959), p. 15. 2. See Olav Riste, The Neutral Ally: Norway’s Relations with Belligerent Powers in the First World War (London: Allen and Unwin, 1965). 3. Reflections of the C-in-C Navy on the Outbreak of War, 3 September 1939, The Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs, 1939–45 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990), pp. 37–38. 4. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 10 October 1939, in ibid. p. 47. 5. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 8 December 1939, Minutes of a Conference with Herr Hauglin and Herr Quisling on 11 December 1939 and Report of the C-in-C Navy, 12 December 1939 in ibid. pp. 63–67. 6. MGFA, Nichols Bohemia, n 172/14, H. W. Schmidt to Admiral Bohemia, 31 January 1955 cited by Francois Kersaudy, Norway, 1940 (London: Arrow, 1990), p. 42. 7. See Andrew Lambert, ‘Seapower 1939–40: Churchill and the Strategic Origins of the Battle of the Atlantic, Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 17, no. 1 (1994), pp. 86–108. 8. For the importance of Swedish iron ore see Thomas Munch-Petersen, The Strategy of Phoney War (Stockholm: Militärhistoriska Förlaget, 1981). 9. Churchill, The Second World War, I, p. 463. 10. See Richard Wiggan, Hunt the Altmark (London: Hale, 1982). 11. TMI, Tome XV, Déposition de l’amiral Raeder, 17 May 1946 cited by Kersaudy, p. 44. 12. Kersaudy, p. 81. 13. Johannes Andenæs, Olav Riste and Magne Skodvin, Norway and the Second World War (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1966), p. -

Research Special Forces.Indd

www.kcl.ac.uk/lhcma a WORLD WAR WORLDTWO WAR Research Guide Swww.kcl.ac.uk/lhcm pecial Forces Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives www.kcl.ac.uk/lhcma a EVANS, Maj P H (1913-1994) LAYCOCK, Maj Gen Sir Robert (1907-1968) Trained with Special Operations Executive (SOE) Commanded Special Service Brigade, ‘Layforce’, in Palestine and Egypt, 1943; served with SOE 1941, and Middle East Commando, 1941-194; Special Forces Force 133, Greece, 1943-1944 commanded Special Service Brigade, UK, Diaries, 1943-1944, detailing SOE training, 1942-1943, for the organisation and training of service as instructor, Allied Military Mission Commandos; Chief of Combined Operations, WORLD WAR TWO This guide offers brief descriptions of material held in the Liddell Commando School, Pendalophos, British 1943-1947 Hart Centre for Military Archives relating to the role of Special relations with Greek partisans, and SOE Completed application forms for volunteer Forces in World War Two. Further biographical information about harassment and demolition activity in Greece; Commando officers [1940]; papers on reports,www.kcl.ac.uk/lhcm 1944, on reconnaissance missions in Commando training, 1940-1941; notes and each of the individuals named and complete summary descriptions the Vitsi area, West Macedonia, Greece, and memoranda on Commando operations, on Operation NOAH’S ARK, Allied and Greek 1941-1942; papers on Operation BLAZING and of the papers held here may be consulted on the Centre’s website resistance missions during the German Operation AIMWELL, for raids on Alderney, (see contact details on the back page), where information about withdrawal from Greece; correspondence 1942; notes on the planning of Operation between Evans and other Allied officers, West CORKSCREW for the capture of Pantelleria, the location of the Centre, opening hours and how to gain access Macedonia, Greece, 1944; captured German Linosa and Lampedusa Islands, Mediterranean, may also be found.