'It's Kriol They're Speaking!' – Constructing Language Boundaries in Multilingual and Ethnically Complex Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Garifuna of Belize's Toledo District Alexander Gough

Indigenous identity in a contested land: A study of the Garifuna of Belize’s Toledo district Alexander Gough This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 Lancaster University Law School 1 Declaration This thesis has not been submitted in support of an application for another degree at this or any other university. It is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated. Many of the ideas in this thesis were the product of discussion with my supervisors. Alexander Gough, Lancaster University 21st September 2018 2 Abstract The past fifty years has seen a significant shift in the recognition of indigenous peoples within international law. Once conceptualised as the antithesis to European identity, which in turn facilitated colonial ambitions, the recognition of indigenous identity and responding to indigenous peoples’ demands is now a well-established norm within the international legal system. Furthermore, the recognition of this identity can lead to benefits, such as a stake in controlling valuable resources. However, gaining tangible indigenous recognition remains inherently complex. A key reason for this complexity is that gaining successful recognition as being indigenous is highly dependent upon specific regional, national and local circumstances. Belize is an example of a State whose colonial and post-colonial geographies continue to collide, most notably in its southernmost Toledo district. Aside from remaining the subject of a continued territorial claim from the Republic of Guatemala, in recent years Toledo has also been the battleground for the globally renowned indigenous Maya land rights case. -

The Song of Kriol: a Grammar of the Kriol Language of Belize

The Song of Kriol: A Grammar of the Kriol Language of Belize Ken Decker THE SONG OF KRIOL: A GRAMMAR OF THE KRIOL LANGUAGE OF BELIZE Ken Decker SIL International DIS DA FI WI LANGWIJ Belize Kriol Project This is a publication of the Belize Kriol Project, the language and literacy arm of the National Kriol Council No part of this publication may be altered, and no part may be reproduced in any form without the express permission of the author or of the Belize Kriol Project, with the exception of brief excerpts in articles or reviews or for educational purposes. Please send any comments to: Ken Decker SIL International 7500 West Camp Wisdom Rd. Dallas, TX 75236 e-mail: [email protected] or Belize Kriol Project P.O. Box 2120 Belize City, Belize c/o e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Copies of this and other publications of the Belize Kriol Project may be obtained through the publisher or the Bible Society Bookstore 33 Central American Blvd. Belize City, Belize e-mail: [email protected] © Belize Kriol Project 2005 ISBN # 978-976-95215-2-0 First Published 2005 2nd Edition 2009 Electronic Edition 2013 CONTENTS 1. LANGUAGE IN BELIZE ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 AN INTRODUCTION TO LANGUAGE ........................................................................................................ 1 1.2 DEFINING BELIZE KRIOL AND BELIZE CREOLE ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 -

The Afro-Nicaraguans (Creoles) a Historico-Anthropological Approach to Their National Identity

MARIÁN BELTRÁN NÚÑEZ ] The Afro-Nicaraguans (Creoles) A Historico-Anthropological Approach to their National Identity WOULD LIKE TO PRESENT a brief historico-anthropological ana- lysis of the sense of national identity1 of the Nicaraguan Creoles, I placing special emphasis on the Sandinista period. As is well known, the Afro-Nicaraguans form a Caribbean society which displays Afro-English characteristics, but is legally and spatially an integral part of the Nicaraguan nation. They are descendants of slaves who were brought to the area by the British between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries and speak an English-based creole. 1 I refer to William Bloom’s definition of ‘national identity’: “[National identity is] that condition in which a mass of people have made the same identification with national symbols – have internalized the symbols of the nation – so that they may act as one psychological group when there is a threat to, or the possibility of enhancement of this symbols of national identity. This is also to say that national identity does not exist simply because a group of people is externally identified as a nation or told that they are a nation. For national identity to exist, the people in mass must have gone through the actual psychological process of making that general identification with the nation”; Bloom, Personal Identity, National Identity and International Relations (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1990): 27. © A Pepper-Pot of Cultures: Aspects of Creolization in the Caribbean, ed. Gordon Collier & Ulrich Fleischmann (Matatu 27–28; Amsterdam & New York: Editions Rodopi, 2003). 190 MARIÁN BELTRÁN NÚÑEZ ] For several hundred years, the Creoles have lived in a state of permanent struggle. -

302232 Travelguide

302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.1> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 5 WELCOME 6 GENERAL VISITOR INFORMATION 8 GETTING TO BELIZE 9 TRAVELING WITHIN BELIZE 10 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 14 CRUISE PASSENGER ADVENTURES Half Day Cultural and Historical Tours Full Day Adventure Tours 16 SUGGESTED OVERNIGHT ADVENTURES Four-Day Itinerary Five-Day Itinerary Six-Day Itinerary Seven-Day Itinerary 25 ISLANDS, BEACHES AND REEF 32 MAYA CITIES AND MYSTIC CAVES 42 PEOPLE AND CULTURE 50 SPECIAL INTERESTS 57 NORTHERN BELIZE 65 NORTH ISLANDS 71 CENTRAL COAST 77 WESTERN BELIZE 87 SOUTHEAST COAST 93 SOUTHERN BELIZE 99 BELIZE REEF 104 HOTEL DIRECTORY 120 TOUR GUIDE DIRECTORY 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.2> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.3> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 The variety of activities is matched by the variety of our people. You will meet Belizeans from many cultural traditions: Mestizo, Creole, Maya and Garifuna. You can sample their varied cuisines and enjoy their music and Belize is one of the few unspoiled places left on Earth, their company. and has something to appeal to everyone. It offers rainforests, ancient Maya cities, tropical islands and the Since we are a small country you will be able to travel longest barrier reef in the Western Hemisphere. from East to West in just two hours. Or from North to South in only a little over that time. Imagine... your Visit our rainforest to see exotic plants, animals and birds, possible destinations are so accessible that you will get climb to the top of temples where the Maya celebrated the most out of your valuable vacation time. -

Nicaragua - Garifuna

Nicaragua - Garifuna minorityrights.org/minorities/garifuna/ June 19, 2015 Profile The Garífuna – also known as Black Caribs – are a people of mixed African and indigenous descent who mainly live in the Pearl Lagoon basin in the communities of Orinoco, La Fé and San Vicente. Besides communities in the Pearl Lagoon basin there are small numbers of Garífunas in Bluefields. Garifuna who live in the Lagoon practice subsistence farming and fishing those in the urban areas live similarly to their Creole neighbors attending local universities and pursuing professional occupations. The majority of Garifuna are bilingual although some indigenous language revival is taking place. With pressure to assimilate into regional cultures the Garifuna language fell into disuse but it has been enjoying a small resurgence. The majority of Garifuna are Catholic but an essential aspect of the culture revolves around maintaining African influenced ancestral traditions based on ritual songs and dances. Historical context Garífuna, entered Nicaragua in 1880 from Honduras after having become a highly marginalized community in that country as a result of having sided with the Spanish loyalists in the 1830 war of independence.(see Honduras). In Nicargua they worked as seasonal loggers in US-owned mahogany camps and earned positions of responsibility within the company hierarchies. The Garifuna already had significant experience working with US companies and in tree felling having at times made up 90% of the labor force that cleared the forested land in Honduras to create the coastal fruit plantations and construct the railroad. 1/2 Being economically favoured newcomers with a closely-knit society, their own special history, language, and African-indigenous based traditions, the Garifuna could exist somewhat independently of other previously established coastal groups. -

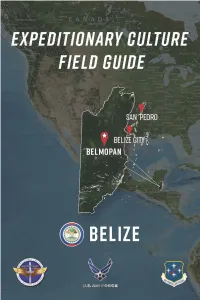

ECFG-Belize-2020R.Pdf

ECFG: Central America Central ECFG: About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Marine shows members of Belize Defense Force how to load ammunition into weapons). The guide consists of 2 E parts: CFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Central America (CENTAM). Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Belize Belizean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: USAF medic checks a Belizean patient’s vision during a medical readiness event). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

Annotations 1963-2005

The Anthropological Caribbeana: Annotations 1963-2005 Lambros Comitas CIFAS Author Title Description Annotation Subject Headings 1977. Les Protestants de la Guadeloupe et la Les Protestants de la Guadeloupe et Author deals with origin of Protestants in Guadeloupe, their social situation, problem of property, and communauté réformée de Capesterre sous Abénon, Lucien la communauté réformée de maintenance of the religion into 18th century. Rather than a history of Protestantism in Guadeloupe, this is an GUADELOUPE. L'Ancien Régime. Bulletin de la Société Capesterre sous L'Ancien Régime. essay on its importance in the religiou d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe 32 (2):25-62. 1993. Caught in the Shift: The Impact of Industrialization on Female-Headed Caught in the Shift: The Impact of Households in Curaçao, Netherlands Antilles. Industrialization on Female-Headed Changes in the social position of women (specifically as reflected in marriage rates and percentages of Abraham, Eva In Where Did All the Men Go? Female- CURAÇAO. Households in Curaçao, Netherlands children born to unmarried mothers) are linked to major changes in the economy of Curaçao. Headed/Female-Supported Households in Antilles Cross-Cultural Perspective. Joan P. Mencher and Anne Okongwu 1976. The West Indian Tea Meeting: An With specific reference to "tea meetings" on Nevis and St. Vincent, author provides a thorough review of the The West Indian Tea Meeting: An Essay in Civilization. In Old Roots in New NEVIS. ST. VINCENT. Abrahams, Roger history and the development of this institution in the British Caribbean. Introduced by Methodist missionaries Essay in Civilization. Lands. Ann M. Pescatello, ed. Pp. 173-208. -

Afro-Latinos in Latin America and Considerations for U.S. Policy

Order Code RL32713 Afro-Latinos in Latin America and Considerations for U.S. Policy Updated November 21, 2008 Clare Ribando Seelke Analyst in Latin American Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Afro-Latinos in Latin America and Considerations for U.S. Policy Summary The 110th Congress has maintained an interest in the situation of Afro-Latinos in Latin America, particularly the plight of Afro-Colombians affected by the armed conflict in Colombia. In recent years, people of African descent in the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking nations of Latin America — also known as “Afro-Latinos” — have been pushing for increased rights and representation. Afro-Latinos comprise some 150 million of the region’s 540 million total population, and, along with women and indigenous populations, are among the poorest, most marginalized groups in the region. Afro-Latinos have formed groups that, with the help of international organizations, are seeking political representation, human rights protection, land rights, and greater social and economic opportunities. Improvement in the status of Afro-Latinos could be difficult and contentious, however, depending on the circumstances of the Afro-descendant populations in each country. Assisting Afro-Latinos has never been a primary U.S. foreign policy objective, although a number of U.S. aid programs benefit Afro-Latinos. While some foreign aid is specifically targeted towards Afro-Latinos, most is distributed broadly through programs aimed at helping all marginalized populations. Some Members support increasing U.S. assistance to Afro-Latinos, while others resist, particularly given the limited amount of development assistance available for Latin America. In the 110th Congress, there have been several bills with provisions related to Afro-Latinos. -

Registration of Belizeans Overseas Connecting with the Diaspora

Registration of Belizeans Overseas Connecting with the Diaspora The Government of Belize is undertaking an exercise to determine the number of Belizeans living overseas and to foster a closer relationship with this overseas community. It is hoped that through this exercise our various Embassies and Consulates will be better able to work with the Government of Belize to address the needs of our Citizens residing overseas by providing more and improved services, and to continue together in the work of developing Belize. The information being gathered through our various Embassies and Consulates will be transmitted to Belize for input into a secure database in the Ministry of Foreign accessible only to those in the ministry directly responsible for the Ministry’s relationship with the Overseas Community. Information submitted to the various Embassies and Consulates will also be retained in those offices to facilitate ease of communication with those persons who have expressed their desire to be involved. The information will not be shared, unless it is specifically requested on the form by those persons who wish to share their skills and talents; and even so contact will be made initially through the Embassy or Consulate through whom the information was submitted. Electronic copies of the form can be found on: www.belize.gov.bz, www.mfa.gov.bz, and on the website of our Embassies and Consulates as shown on our Ministry’s website contact details. In conducting this exercise the form requests some specific information – marked with an asterisk – which is required if the exercise is to be successful in determining the number of Belizeans living overseas and in what Country ( and State) they are concentrated. -

Redalyc.Diaspora Sounds from Caribbean Central America

Caribbean Studies ISSN: 0008-6533 [email protected] Instituto de Estudios del Caribe Puerto Rico Stone, Michael Diaspora Sounds from Caribbean Central America Caribbean Studies, vol. 36, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2008, pp. 221-235 Instituto de Estudios del Caribe San Juan, Puerto Rico Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=39215107020 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative WATCHING THE CARIBBEAN...PART II 221 Diaspora Sounds from Caribbean Central America Michael Stone Program in Latin American Studies Princeton University [email protected] Garifuna Drum Method. Produced by Emery Joe Yost and Matthew Dougherty. English and Garifuna with subtitles. Distributed by End of the Line Productions/ Lubaantune Records, 2008. DVD. Approximately 100 minutes, color. The Garifuna: An Enduring Spirit. Produced by Robert Flanagan and Suzan Al-Doghachi. English and Garifuna with subtitles. Lasso Pro- ductions, 2003. Distributed by Lasso Productions. DVD. 35 minutes, color. The Garifuna Journey. Produced by Andrea Leland and Kathy Berger. English and Garifuna with subtitles. New Day Films, 1998. Distributed by New Day Films. DVD and study guide. 47 minutes, color. Play, Jankunú, Play: The Garifuna Wanáragua Ritual of Belize. Produced by Oliver Greene. English and Garifuna with subtitles. Distributed by Documentary Educational Resources, 2007. DVD. 45 minutes, color. Trois Rois/ Three Kings of Belize. Produced by Katia Paradis. English, Spanish, Garifuna, and K’ekchi Maya with subtitles (French-language version also available). -

1 Language Use, Language Change and Innovation In

LANGUAGE USE, LANGUAGE CHANGE AND INNOVATION IN NORTHERN BELIZE CONTACT SPANISH By OSMER EDER BALAM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance and support from many people, who have been instrumental since the inception of this seminal project on contact Spanish outcomes in Northern Belize. First and foremost, I am thankful to Dr. Mary Montavon and Prof. Usha Lakshmanan, who were of great inspiration to me at Southern Illinois University-Carbondale. Thank you for always believing in me and motivating me to pursue a PhD. This achievement is in many ways also yours, as your educational ideologies have profoundly influenced me as a researcher and educator. I am indebted to my committee members, whose guidance and feedback were integral to this project. In particular, I am thankful to my adviser Dr. Gillian Lord, whose energy and investment in my education and research were vital for the completion of this dissertation. I am also grateful to Dr. Ana de Prada Pérez, whose assistance in the statistical analyses was invaluable to this project. I am thankful to my other committee members, Dr. Benjamin Hebblethwaite, Dr. Ratree Wayland, and Dr. Brent Henderson, for their valuable and insighful comments and suggestions. I am also grateful to scholars who have directly or indirectly contributed to or inspired my work in Northern Belize. These researchers include: Usha Lakshmanan, Ad Backus, Jacqueline Toribio, Mark Sebba, Pieter Muysken, Penelope Gardner- Chloros, and Naomi Lapidus Shin. -

Correlates of Sexual Initiation Among Belizeans: Implications for HIV Risk

Correlates of Sexual Initiation among Belizeans: Implications for HIV Risk Background and Significance The social meaning and significance of sexual initiation varies by culture, however, it remains a milestone in the physical and psychological development of both men and women throughout the world. Consequently, the timing of sexual debut is an important transition in a person’s reproductive trajectory; it represents changes in interpersonal relationships and decision-making processes. Furthermore, the context within which it occurs can have immediate and far-reaching consequences for the individual. Sexual initiation heralds the onset of possible exposure to unexpected and undesirable reproductive outcomes such as unplanned pregnancies, sexually transmitted diseases including HIV, and even infertility. A fair amount of research have implicated early sexual debut as a factor in subsequent risky sex-related behaviours such as inconsistent condom use and increased number of lifetime partners. Actually, delaying sexual initiation has been credited as one of the behaviour changes that contributed to the decline of HIV in Uganda. In many developed countries sexual debut typically occurs during adolescence; by age 20 usually about 80% of young adults are sexually experienced. Furthermore, countries of varied economic development are witnessing younger ages of sexual initiation with each subsequent generation. Globalization, advancing economic development, increased autonomy of women and the diminishing role of the church have been posited as social forces influencing this phenomenon. National boundaries are increasingly unable to constrain ideas, customs or behaviour as the vast apparatus of consumerism traverses the world. Thus, worldwide advances in human and economic development precipitate economic and cultural changes.