The Mother Series: a Study of Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pe/Uasdj Sm6|J Nv *3K11 'Smolxvianls Oloaxvhxs Aq'z

pe/uasdj sm6|j nv *3K11 'SMOlXViaNlS OlOaXVHXS Aq'z«6P<S ■ ' • a a c T : r - - 8 - - 81 - - zt - It - - - J91H1 SI - - II - 9S SI - - 6 - SS 2S - - yaiHoiJ - - - - - - - - - - - 8fr - VZ SS 9C 01 SC tl ts 6 ss 8 SI L 9S Sl7 9 OS s VJklOW - - - Z^ - \z - IS - 2S - 6V - s St LZ SC zz 9Z OS 9 17 81 Z 62 2 S2 I aaouva - - - - - - frt- - - - - _ 617 - - - QZ 6C LZ 17S LZ 61 92 OS 22 Z^ LI 62 IS OZ Z£ ^Z IS 8 L t S2 81 S S2 2 12 I isaiyj - - - - - - - - 9S - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - IS 9V OS SS - - Ofr - 817 6C - 8S Sl7 tz ss ts VI 01 It 6 91 Zl 9C SI ss II 17C 8 S2 12 L 9 CI s oyvziM SI *f CI ZI II 01 6 8 L 9 c c c I laATi sseiD Xq si3A»i lusjaj^a ie 3iqe|{EAV S||9ds •(aApeiniunD) aAjpv = V '(aAijeinLunD ^ou) V/D 2 D k i i a k i i g 2 OS 3AlSSBd = r d l e q u j o a - u o w = k l " j e q u j o o = 3 V/D T D k i i a k i i g I 62 liAVOl -:j, 'uo3Buna=a 'ss3UJ3pi!/V\ =A\ V/D tssakNvaM t 82 '3J3qAv03A3 = a rapnput S3d>^ I|3dS . V/D S S S 3 k i y V 3 M S LZ V/D 2 S S 3 k I M V 3 A \ 2 92 AID A D v y n D D V A i y v d V 9S V/D I s s a k i M v a m I S2 A/0 ADVynDDV z SS V/D t k i o i s n j k i o D t t2 1/kl KioiiviyodSkivyx 2 ts V/D s k i o i s n x k i o D S S2 om/u uoiivmvAa yaiswow V 2S V/D 2 k i o i s n j k i o D 2 22 V/D USMVMV Z IS V/D I k i o i s n j k i o D I X2 A/O I v r w i k i 2 OS d/D t k i o i x D a x o y d t 02 V/D avaakin nadsia T 6t d/D s k i o i x D a x o y d S 6X A/O lVlkI3W313 kiowwns V 817 d/D 2 k i o i x D a x o y d 2 8X V/D aAiossia Z LV d/D I k i o i x D a x o y d X LI V/D yv3J 2 9V d/D 2 a w v n j M o y y v A x y v d t 91 -

M.A. Russian 2019

************ B+ Accredited By NAAC Syllabus For Master of Arts (Part I and II) (Subject to the modifications to be made from time to time) Syllabus to be implemented from June 2019 onwards. 2 Shivaji University, Kolhapur Revised Syllabus For Master of Arts 1. TITLE : M.A. in Russian Language under the Faculty of Arts 2. YEAR OF IMPLEMENTATION: New Syllabus will be implemented from the academic year 2019-20 i.e. June 2019 onwards. 3. PREAMBLE:- 4. GENERAL OBJECTIVES OF THE COURSE: 1) To arrive at a high level competence in written and oral language skills. 2) To instill in the learner a critical appreciation of literary works. 3) To give the learners a wide spectrum of both theoretical and applied knowledge to equip them for professional exigencies. 4) To foster an intercultural dialogue by making the learner aware of both the source and the target culture. 5) To develop scientific thinking in the learners and prepare them for research. 6) To encourage an interdisciplinary approach for cross-pollination of ideas. 5. DURATION • The course shall be a full time course. • The duration of course shall be of Two years i.e. Four Semesters. 6. PATTERN:- Pattern of Examination will be Semester (Credit System). 7. FEE STRUCTURE:- (as applicable to regular course) i) Entrance Examination Fee (If applicable)- Rs -------------- (Not refundable) ii) Course Fee- Particulars Rupees Tuition Fee Rs. Laboratory Fee Rs. Semester fee- Per Total Rs. student Other fee will be applicable as per University rules/norms. 8. IMPLEMENTATION OF FEE STRUCTURE:- For Part I - From academic year 2019 onwards. -

Informa PLC Interim Results for Six Months to 30 June 2016 Continued Operational and Financial Progress in Peak Year of GAP Investment

Press Release 28 July 2016 Informa PLC Interim Results for Six Months to 30 June 2016 Continued Operational and Financial Progress in Peak Year of GAP investment KEY FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Accelerating organic revenue growth: +2.5% vs +0.2% in H1 2015 and +1.0% FY 2015 Higher reported revenue: +4.7% to £647.7m (H1 2015: £618.8m) Increased adjusted operating profit: +6.3% to £202.2m (H1 2015: £190.3m) Higher statutory operating profit: +8.6% to £141.6m (H1 2015: £130.4m*) Growth in adjusted diluted EPS: +3.1% to 23.1p (H1 2015: 22.4p*) Increased interim dividend: up 4% to 6.80p (H1 2015: 6.55p) Robust balance sheet with secure pension position: Gearing of 2.4x (H1 2015: 2.4x) Strong underlying free cash flow, full year on track; first-half phasing with £20m GAP investment: £67.7m (H1 2015: £116.4m) London: Informa (LSE: INF.L), the international Business Intelligence, Exhibitions, Events and Academic Publishing Group, today reported solid growth in Revenue, Operating Profit and Earnings Per Share for the six months to 30 June 2016 in the peak investment year of the 2014-2017 Growth Acceleration Plan (“GAP”). Operational and Financial Momentum in peak year of GAP Investment – robust trading and improving earnings visibility in all four Operating Divisions: o Global Exhibitions…Growing: Benefits of high quality Brand portfolio, scale and US expansion delivering continued double-digit growth; o Academic Publishing…Resilient: Simplified operating structure, focus on Upper Level Academic Market and further investment in specialist content -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

Atari 8-Bit Family

Atari 8-bit Family Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 221B Baker Street Datasoft 3D Tic-Tac-Toe Atari 747 Landing Simulator: Disk Version APX 747 Landing Simulator: Tape Version APX Abracadabra TG Software Abuse Softsmith Software Ace of Aces: Cartridge Version Atari Ace of Aces: Disk Version Accolade Acey-Deucey L&S Computerware Action Quest JV Software Action!: Large Label OSS Activision Decathlon, The Activision Adventure Creator Spinnaker Software Adventure II XE: Charcoal AtariAge Adventure II XE: Light Gray AtariAge Adventure!: Disk Version Creative Computing Adventure!: Tape Version Creative Computing AE Broderbund Airball Atari Alf in the Color Caves Spinnaker Software Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves Quality Software Alien Ambush: Cartridge Version DANA Alien Ambush: Disk Version Micro Distributors Alien Egg APX Alien Garden Epyx Alien Hell: Disk Version Syncro Alien Hell: Tape Version Syncro Alley Cat: Disk Version Synapse Software Alley Cat: Tape Version Synapse Software Alpha Shield Sirius Software Alphabet Zoo Spinnaker Software Alternate Reality: The City Datasoft Alternate Reality: The Dungeon Datasoft Ankh Datamost Anteater Romox Apple Panic Broderbund Archon: Cartridge Version Atari Archon: Disk Version Electronic Arts Archon II - Adept Electronic Arts Armor Assault Epyx Assault Force 3-D MPP Assembler Editor Atari Asteroids Atari Astro Chase Parker Brothers Astro Chase: First Star Rerelease First Star Software Astro Chase: Disk Version First Star Software Astro Chase: Tape Version First Star Software Astro-Grover CBS Games Astro-Grover: Disk Version Hi-Tech Expressions Astronomy I Main Street Publishing Asylum ScreenPlay Atari LOGO Atari Atari Music I Atari Atari Music II Atari This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Super Smash Bros. Melee) X25 - Battlefield Ver

BATTLEFIELD X04 - Battlefield T02 - Menu (Super Smash Bros. Melee) X25 - Battlefield Ver. 2 W21 - Battlefield (Melee) W23 - Multi-Man Melee 1 (Melee) FINAL DESTINATION X05 - Final Destination T01 - Credits (Super Smash Bros.) T03 - Multi Man Melee 2 (Melee) W25 - Final Destination (Melee) W31 - Giga Bowser (Melee) DELFINO'S SECRET A13 - Delfino's Secret A07 - Title / Ending (Super Mario World) A08 - Main Theme (New Super Mario Bros.) A14 - Ricco Harbor A15 - Main Theme (Super Mario 64) Luigi's Mansion A09 - Luigi's Mansion Theme A06 - Castle / Boss Fortress (Super Mario World / SMB3) A05 - Airship Theme (Super Mario Bros. 3) Q10 - Tetris: Type A Q11 - Tetris: Type B Metal Cavern 1-1 A01 - Metal Mario (Super Smash Bros.) A16 - Ground Theme 2 (Super Mario Bros.) A10 - Metal Cavern by MG3 1-2 A02 - Underground Theme (Super Mario Bros.) A03 - Underwater Theme (Super Mario Bros.) A04 - Underground Theme (Super Mario Land) Bowser's Castle A20 - Bowser's Castle Ver. M A21 - Luigi Circuit A22 - Waluigi Pinball A23 - Rainbow Road R05 - Mario Tennis/Mario Golf R14 - Excite Truck Q09 - Title (3D Hot Rally) RUMBLE FALLS B01 - Jungle Level Ver.2 B08 - Jungle Level B05 - King K. Rool / Ship Deck 2 B06 - Bramble Blast B07 - Battle for Storm Hill B10 - DK Jungle 1 Theme (Barrel Blast) B02 - The Map Page / Bonus Level Hyrule Castle (N64) C02 - Main Theme (The Legend of Zelda) C09 - Ocarina of Time Medley C01 - Title (The Legend of Zelda) C04 - The Dark World C05 - Hidden Mountain & Forest C08 - Hyrule Field Theme C17 - Main Theme (Twilight Princess) C18 - Hyrule Castle (Super Smash Bros.) C19 - Midna's Lament PIRATE SHIP C15 - Dragon Roost Island C16 - The Great Sea C07 - Tal Tal Heights C10 - Song of Storms C13 - Gerudo Valley C11 - Molgera Battle C12 - Village of the Blue Maiden C14 - Termina Field NORFAIR D01 - Main Theme (Metroid) D03 - Ending (Metroid) D02 - Norfair D05 - Theme of Samus Aran, Space Warrior R12 - Battle Scene / Final Boss (Golden Sun) R07 - Marionation Gear FRIGATE ORPHEON D04 - Vs. -

Amazon Charts Ask Iwata: Words of Wisdom from Nintendo's Legendary CEO for Ipad

On my business card, I am a corporate president. In my mind, I am a game developer. But in my heart, I am a gamer. —Satoru IwataSatoru Iwata was the former Global President and CEO of Nintendo and a gifted programmer who played a key role in the creation of many of the world’s best-known games. He led the production of innovative platforms such as the Nintendo DS and the Wii, and laid the groundwork for the development of the wildly successful Pokémon Go game and the Nintendo Switch. Known for his analytical and imaginative mind, but even more for his humility and people-first approach to leadership, Satoru Iwata was beloved by game fans and developers worldwide. In this motivational collection, Satoru Iwata addresses diverse subjects such as locating bottlenecks, how success breeds resistance to change, and why programmers should never say no. Drawn from the Iwata Asks series of interviews with key contributors to Nintendo games and hardware, and featuring conversations with renowned Mario franchise creator Shigeru Miyamoto and creator of EarthBound Shigesato Itoi, Ask Iwata offers game fans and business leaders an insight into the leadership, development and design philosophies of one of the most beloved figures in gaming history. https://keepsmile241.blogspot.com/?book=197472154X Amazon Charts Ask Iwata: Words of Wisdom from Nintendo's Legendary CEO For Ipad Description On my business card, I am a corporate president. In my mind, I am a game developer. But in my heart, I am a gamer. —Satoru IwataSatoru Iwata was the former Global President and CEO of Nintendo and a gifted programmer who played a key role in the creation of many of the world’s best-known games. -

Best Wishes to All of Dewey's Fifth Graders!

tiger times The Voice of Dewey Elementary School • Evanston, IL • Spring 2020 Best Wishes to all of Dewey’s Fifth Graders! Guess Who!? Who are these 5th Grade Tiger Times Contributors? Answers at the bottom of this page! A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R Tiger Times is published by the Third, Fourth and Fifth grade students at Dewey Elementary School in Evanston, IL. Tiger Times is funded by participation fees and the Reading and Writing Partnership of the Dewey PTA. Emily Rauh Emily R. / Levine Ryan Q. Judah Timms Timms Judah P. / Schlack Nathan O. / Wright Jonah N. / Edwards Charlie M. / Zhu Albert L. / Green Gregory K. / Simpson Tommy J. / Duarte Chaya I. / Solar Phinny H. Murillo Chiara G. / Johnson Talula F. / Mitchell Brendan E. / Levine Jojo D. / Colledge Max C. / Hunt Henry B. / Coates Eve A. KEY: ANSWER KEY: ANSWER In the News Our World............................................page 2 Creative Corner ..................................page 8 Sports .................................................page 4 Fun Pages ...........................................page 9 Science & Technology .........................page 6 our world Dewey’s first black history month celebration was held in February. Our former principal, Dr. Khelgatti joined our current Principal, Ms. Sokolowski, our students and other artists in poetry slams, drumming, dancing and enjoying delicious soul food. Spring 2020 • page 2 our world Why Potatoes are the Most Awesome Thing on the Planet By Sadie Skeaff So you know what the most awesome thing on the planet is, right????? Good, so you know that it is a potato. And I will tell you why the most awesome thing in the world is a potato, and you will listen. -

Computer Gaming World Issue

VOL. 2 NO. 2 MAR. - APR. 1982 Features SOUTHERN COMMAND 6 Review of SSI's Yom Kippur Wargame Bob Proctor SO YOU WANT TO WRITE A COMPUTER GAME 10 Advice on Game Designing Chris Crawford NAPOLEON'S CAMPAIGNS 1813 & 1815: SOME NOTES 12 Player's, Designer's, and Strategy Notes Joie Billings SO YOU WANT TO WIN A MILLION 16 Analysis of Hayden's Blackjack Master Richard McGrath ESCAPE FROM WOLFENSTEIN 18 Short Stay Based on the Popular Game Ed Curtis ODE TO JOY, PADDLE AND PORT: 19 Some Components for Game Playing Luther Shaw THE CURRENT STATE OF 21 COMPUTER GAME DOCUMENTATION Steve Rasnic Tern NORDEN+, ROBOT KILLER 25 Winner of CGW's Robotwar Tournament Richard Fowell TIGERS IN THE SNOW: A REVIEW 30 Richard Charles Karr YOU TOO CAN BE AN ACE 32 Ground School for the A2-FS1 Flight Simulator Bob Proctor BUG ATTACK: A REVIEW 34 Cavalier's New Arcade Game Analyzed Dave Jones PINBALL MANIA 35 Review of David's Midnight Magic Stanley Greenlaw Departments From the Editor 2 Hobby & Industry News 2 Initial Comments 3 Letters 3 The Silicon Cerebrum 27 Micro Reviews 36 Reader's Input Device 40 From the Editor... Each issue of CGW brings the magazine closer Input Device". Not only will it help us to know just to the format we plan to achieve. This issue (our what you want to read, it will also let the man- third) is expanded to forty pages. Future issues ufacturers know just what you think about the will be larger still. games on the market. -

Annual Copyright License for Corporations

Responsive Rights - Annual Copyright License for Corporations Publisher list Specific terms may apply to some publishers or works. Please refer to the Annual Copyright License search page at http://www.copyright.com/ to verify publisher participation and title coverage, as well as any applicable terms. Participating publishers include: Advance Central Services Advanstar Communications Inc. 1105 Media, Inc. Advantage Business Media 5m Publishing Advertising Educational Foundation A. M. Best Company AEGIS Publications LLC AACC International Aerospace Medical Associates AACE-Assn. for the Advancement of Computing in Education AFCHRON (African American Chronicles) AACECORP, Inc. African Studies Association AAIDD Agate Publishing Aavia Publishing, LLC Agence-France Presse ABC-CLIO Agricultural History Society ABDO Publishing Group AHC Media LLC Abingdon Press Ahmed Owolabi Adesanya Academy of General Dentistry Aidan Meehan Academy of Management (NY) Airforce Historical Foundation Academy Of Political Science Akademiai Kiado Access Intelligence Alan Guttmacher Institute ACM (Association for Computing Machinery) Albany Law Review of Albany Law School Acta Ecologica Sinica Alcohol Research Documentation, Inc. Acta Oceanologica Sinica Algora Publishing ACTA Publications Allerton Press Inc. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae Allied Academies Inc. ACU Press Allied Media LLC Adenine Press Allured Business Media Adis Data Information Bv Allworth Press / Skyhorse Publishing Inc Administrative Science Quarterly AlphaMed Press 9/8/2015 AltaMira Press American -

Dusty Rooms: Il Fenomeno Di Mother

Dusty Rooms: il fenomeno di Mother Proprio qualche giorno fa, esattamente il 27 Luglio, è stato il 29esimo anniversario del rilascio del primo gioco della saga di Mother su Famicom. Negli ultimi anni la saga è diventata un fenomeno di culto, specialmente grazie all’inclusione di Ness in Super Smash Bros. Melee e, grazie a esso, un’orda di fan non fa che chiedere a gran voce il rilascio di tutti i giochi della saga in media più recenti, specialmente sapendo che il creatore della saga, Shigesato Itoi, ha dichiarato che con il rilascio di Mother 3 la saga è ufficialmente terminata e non ha alcuna intenzione di rilasciare un eventuale Mother 4. Oggi, su Dusty Rooms, daremo uno sguardo a una delle serieRPG più sottovalutate di tutti i tempi, che ha riscoperto una nuova vita grazie a internet ma che, ai tempi, non riuscì a imporsi in confronto ai più popolari Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest o Phantasy Star. Un inizio un po’ sottotono La storia di Mother, come già accennato, comincia su Famicom nel Luglio del 1989. Il prologo della storia ci presenta George e Maria, una tipica coppia americana che intorno agli anni ’50 scomparve dalla circolazione; più tardi George riapparve improvvisamente ma non rivelò mai a nessuno dove si trovasse e cosa successe a lui e a sua moglie, che rimase dispersa. George dunque, si chiuse in se stesso e cominciò a fare strani esperimenti isolandosi dal mondo. Nei tardi anni ’80 un giovane di nome Ninten (è il suo nome standard ma – come poi diventerà tipico della serie – è possibile cambiarlo prima di cominciare la nostra avventura) è testimone distrani eventi paranomali che avvengono in casa sua, come appunto l’attacco della sua bajour. -

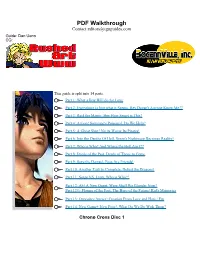

Chrono Cross Strategy Guide

PDF Walkthrough Contact:[email protected] Guide: Dan Ueno CG: This guide is split into 14 parts. Part 1: What a Boy Will do for Love Part 2: Everything is Not what it Seems, Hey Doesn't Anyone Know Me?? Part 3: Raid the Manor, Hey How Smart is This? Part 4: Action! Someone's Poisoned, Do We Help? Part 5: A Ghost Ship? No its Worse Its Pirates! Part 6: Into the Depths Of Hell, Serge's Nightmare Becomes Reality! Part 7: Who is Who? And Where the Hell Am I?? Part 8: Deeds of the Past, Deeds of Those to Come Part 9: Save the Damsel, Foes Are Friends! Part 10: Another Task to Complete, Defeat the Dragons! Part 11: Serge VS. Lynx, Who is Who?? Part 12: Ah! A New Quest, Were Shall We Blunder Now? Part 12½: Flames of the Past, The Hero of the Future! Kid's Memories Part 13: Opposites Attract! Creation From Love and Hate / Fin Part 14: New Game+ New Foes!, What Do We Do With Them? Chrono Cross Disc 1 Chrono Cross Disc 1 An Introduction, a Square tradition. The game starts with an FMV of a tower surrounded by statuary of dragons. We are introduced to Razzly, Kid, and Serge. This may not be your group. The third member other than Serge and Kid rotates. As things start, head to the right. The left side just shows a power crystal. (your goal) Continue down the path and follow the left side of the screen until you reach the outside door.