(Art and Transition in the Region of Former Yugoslavia) (Forthcomin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zbornik Ob 20-Letnici MKK Bela Krajina

CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 061.2-053.6(497.4Črnomelj)(091) ALTERNATIVA na margini : 20 let MKK BK / [pisci člankov Igor Bašin ... [et al.] ; urednik, pisec spremne besede Janez Weiss ; fotografije Marko Pezdirc ... et al.]. - Črnomelj : Mladinski kulturni klub Bele krajine, 2010 1. Bašin, Igor 2. Weiss, Janez, 1978- 3. Mladinski kulturni klub Bele krajine (Črnomelj) 250618880 To ni eulogija, to ni epitaf! Konec najstni{ kih let. Hormonalne nestabilnosti so prebrodene in zdaj smo tu, v jutru dvajsetih, ponosni na dve desetletji dela, hkrati pa tudi želje po nadaljnjem delu, razvoju, rasti in novih zmagah. Dvajset let ne smemo pustiti mimo brez opisa, brez spomenika na{ emu trudu, delu in naivnostim. Zato smo se odlo~ ili zbrati prispevke, spomine, pisane in fotografirane, in jih obelodaniti, da ne bi v megli pozabe izginila na{{ a stremenja, na drobec k razvoju celote, tak { ne in druga~ ne, belokranjske, slovenske, evropske, globalne. Rad bi se zahvalil vsem, ki so brez nepotrebnega prepri~ evanja pristopili k projektu in pomagali pri njegovi realizaciji. Hvala Marku Zupani~{ u, Bo tjanu [ vajgerju, Heleni Vuk {~ ini , Robiju Lozarju, Du{{~ anu Jesihu, Samerju Khalilu, Igorju Ba inu, Branetu Koncilji, Goranu Jarnevi u, Juliju Karinu in Sa{~ u Jankovi u za besede ter Bo { tjanu Matja {~u i u, Mark Pezdircu, Tomu Urhu, Ireni Pov { e in Ga{~ perju Gregori u za foto utrinke. Poudariti moram, da klub nikakor ni le delo nas objavljenih tukaj, ravno obratno, je delo in prizadevanje kopice ljudi, ki so tokom dveh desetletij s svojo voluntersko in udarni{ ko voljo v najve~~i{{~~ ji meri omogo li obstanek in utrip na ega dru tva. -

Trešnjevka U Očima Trešnjevčana Riječ Urednika

broj 40/41 jesen / zima 2017. BESPLATNO KVARTOVSKO GLASILO CEKATE: PROJEKT ABBA EUROPE KVARTOVSKA POVIJEST: SVI ŽIVOTI TREŠNJEVAČKIH ULIČNIH LOKALA POZNATI IZ SUSJEDSTVA: INTERVJU: KRISTIAN NOVAK IstražIvanje kvarta Trešnjevka u očima Trešnjevčana riječ urednika Dragi Trešnjevčani, Kao i uvijek u predblagdansko vrijeme donosimo vam novi broj s nizom zanimlji- vih tema o našem kvartu. Predstavljamo predsjednike vijeća grad- skih četvrti izabranih na prošlim lokal- nim izborima kao i predsjednike mjesnih odbora. Zanimali su nas planovi i prioriteti Novosti iz četvrti rada kao i ideje poboljšanja života. Sjećamo se i dvije posebno drage osobe koje su nas napustile. Naša kolegica Kri- stina Radošević je više od 20 godina radeći u Centru za kulturu Trešnjevka ostavila Idemo u veliki trag u nama i u samom Centru, a sje- ćamo se i dobrog duha Trešnjevke Zvonka CeKaTe Špišića i njegove „Trešnjevačke balade“. Naša četvrt je inspirativna studentima sociologije, donosimo istraživanje o identi- tetu kvarta. Informiramo vas i o novom por- Trešnjevačka posla talu koji bilježi ritam Trešnjevke. Posjetili smo i Gimnaziju u Dobojskoj koja svojim radom stalno donosi živost. I u CeKaTeu je dosta novosti – krenuo 2 je veliki međunarodni projekt a naš izlog Od 7 do 107 krase i pjesničko-slikarski radovi u okviru projekta „Prozor / prizor CeKaTea“. Spa- jamo pjesnike i likovne umjetnike i njihove posuđene radove izlažemo na mjesec dana poslije ekskluzivnog doručka s pjesnikom i slikarom za odabrane. Posjetili smo Dom za starije osobe Trešnjevka i vidjeli da je i tamo živo i zani- mljivo i da Grad na više načina skrbi o najugroženijim Trešnjevčanima. U intervju nam književnik Kristian Poznati iz susjedstva Novak otkriva kako je živjeti na Trešnjevci, a predstavljamo i okupljalište na Novoj cesti – klub No Sikiriki koji je već postao kultno mjesto u koji dolaze znatiželjnici iz svih dijelova grada „kako se ne bi sekirali“. -

Kelt Pub Karaoke Playlista SLO in EX-YU

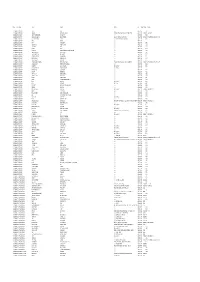

Kelt pub Karaoke playlista SLO in EX-YU Colonia 1001 noc 25001 Oto Pestner 30 let 25002 Aerodrom Fratello 25066 Agropop Ti si moj soncek 25264 Aleksandar Mezek Siva pot 25228 Alen Vitasovic Gusti su gusti 25072 Alen Vitasovic Jenu noc 25095 Alen Vitasovic Ne moren bez nje 25163 Alfi Nipic Ostal bom muzikant 25187 Alfi Nipic Valcek s teboj 25279 Alka Vuica Lazi me 25118 Alka Vuica Otkad te nema 25190 Alka Vuica Profesionalka 25206 Alka Vuica Varalica 25280 Atomik Harmonik Brizgalna brizga 25021 Atomik Harmonik Hop Marinka 25079 Atomik Harmonik Kdo trka 25109 Azra A sta da radim 25006 Azra Balkan 25017 Azra Fa fa 25064 Azra Gracija 25071 Azra Lijepe zene prolaze kroz grad25123 Azra Pit i to je Amerika 25196 Azra Uzas je moja furka 25278 Bajaga 442 do Beograda 25004 Bajaga Dobro jutro dzezeri 25051 Bajaga Dvadeseti vek 25058 Bajaga Godine prolaze 25070 Bajaga Jos te volim 25097 Bajaga Moji drugovi 25148 Bajaga Montenegro 25149 Bajaga Na vrhovima prstiju 25154 Bajaga Plavi safir 25199 Bajaga Sa druge strane jastuka 25214 Bajaga Tamara 25253 Bajaga Ti se ljubis 25259 Bajaga Tisina 25268 Bajaga Zazmuri 25294 Bebop Ti si moje sonce 25266 Bijelo Dugme A ti me iznevjeri 25007 Bijelo dugme Ako ima Boga 25008 Bijelo dugme Bitanga i princeza 25019 Bijelo dugme Da mi je znati koji joj je vrag25033 Bijelo dugme Da sam pekar 25034 Bijelo Dugme Djurdjevdan 25049 Bijelo dugme Evo zaklet cu se 25063 Bijelo dugme Hajdemo u planine 25077 Bijelo dugme Ima neka tajna veza 25083 Bijelo dugme Jer kad ostari{ 25096 Bijelo dugme Kad zaboravis juli 25106 Bijelo -

Popular Music and Narratives of Identity in Croatia Since 1991

Popular music and narratives of identity in Croatia since 1991 Catherine Baker UCL I, Catherine Baker, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated / the thesis. UMI Number: U592565 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592565 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 Abstract This thesis employs historical, literary and anthropological methods to show how narratives of identity have been expressed in Croatia since 1991 (when Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia) through popular music and through talking about popular music. Since the beginning of the war in Croatia (1991-95) when the state media stimulated the production of popular music conveying appropriate narratives of national identity, Croatian popular music has been a site for the articulation of explicit national narratives of identity. The practice has continued into the present day, reflecting political and social change in Croatia (e.g. the growth of the war veterans lobby and protests against the Hague Tribunal). -

Problem Ne Leži U ACTA Sporazumu Ili U Autorskim Pravima, Već U Nereguliranom Internetskom Tržištu Glazbe Piše: Marina Ferić Jančić

STIPENDISTI FONDA MATZ / ROđENDANI SILVIJA FORETIćA I DUšANA PrašELJA / NOVE MUZIKOLOšKE SNAGE: AKTIVNOSTI FUsNOTE / IN MEMORIAM MARKO RUŽDJAK / RECENZIJE NOTNIH IZDANJA / CD IZLOG NOVINE HRVATSKOGA DRUŠTVA SKLADATELJA BROJ 173 OŽUJAK 2012. CIJENA 20 kn ISSN 1330–4747 Problem ne leži u ACTA sporazumu ili u autorskim pravima, već u nereguliranom internetskom tržištu glazbe Piše: Marina Ferić Jančić očetak veljače uvelike su obilje– Naime, svjesni činjenice da su gra– Pžila i događanja oko ACTA–e, đani željni kvalitetne i povoljne le– Međunarodnog trgovačkog spora– galne glazbene ponude, stupili smo zuma o borbi protiv krivotvorenja i u kontakt s međunarodnim glazbe– piratstva kojemu je pristupila i Eu– nim servisima s pitanjem zašto ih ropska unija, no koji u svojim naci– u našoj zemlji nema i pozivom da onalnim parlamentima nisu ratifici– dođu u Hrvatsku. rale neke zemlje članice Unije. Popularni iTunesi na naš su upit vrlo Pristupanje Unije sporazumu bilo je kratko odgovorili da zasad dola– povodom mnogih prosvjeda održa– zak u Hrvatsku nije u njihovu pla– nih diljem Europe, pa i u Hrvatskoj. nu. To je ujedno bio i jedini kontakt Mnogi prosvjednici i poneki politi– koji smo ikada s njima imali. Strea– čari, više ili manje upućeni, iznijeli ming servisi poput Spotify i Deezer s su ozbiljne kritike o mogućoj ugro– nama su više komunicirali te izrazi– ženosti ljudskih prava i građanskih li određeno zanimanje za dolaskom sloboda. Međutim, važno je raza– na ovo tržište. No, uz to su nezao– znati što je od svega izrečenog toč– bilazno išla -

DJ Goce Started to Get Involved Into Hip Hop Culture in the Early 90'S

DJ Goce started to get involved into hip hop culture in the early 90's. In 1993 his group S.A.F. put out their first demo on the radio, by 1996 S.A.F. had studio recordings, was on the top of independent radio charts and started doing live shows. In 1998 signed a deal with Polygram imprint Indigo that ended up canceled because of regional tensions and wars. In 2000 S.A.F. finally released their LP "Safizam" (recorded between '96-'98) completely produced by DJ Goce. In 2001 S.A.F. did a big show together with special guests Das Efx to promote Safizam, and in 2002 released "Safizam" as 3LP set - the first hip hop vinyl release on Balkans! In 2015 SAF marked 15 years of Safizam LP, with a sold out concert in Skopje https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VzhZ29jTXFI In 2002 DJ Goce together with his partner Dimitri from Cair formed Bootlegz entertainment and started the first hip-hop resident club night in Macedonia at the club Element. In 2002 Bootlegz released "Bootlegz mixtape vol.1" mixed by DJ Goce, first official mixtape in Macedonia, and was released on Tape! DJ Goce produced a lot of local Macedonian and regional artists thru the years, worked as a co-producer and DJ of the TV Show "Hip Hop Teza" on national A1 TV and as a DJ of Hip Hop Teza radio show on Top FM. In 2008 DJ Goce and Dimitri from Cair organized and hosted the first Turntablism workshop in Macedonia that featured DJ Strajk, DJ Venom (Ex-YU DMC Champ) and as a special guest - DJ Rondevu, and second one in 2011 with DJ Raid (PG4/filter crew) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z1wb3LdxalM In 2016 together with DJ Chvare formed the promotional crew Funky Fresh http://www.funkyfresh.es , in order to bring freshness to the night life in their hometown, and did events with Fred Wesley, Roy Ayers, Gang Starr Foundation, Dj Angelo, Large Pro, Diamond D, Jeru the Damaja , The Beatnuts, Lord Finesse ,Natasha Diggs, Dusty Donuts, Boca 45, Jon 1st etc. -

The Influence of English on Croatian Hip-Hop Language

The Influence of English on Croatian Hip-Hop Language Kozjak, Marija Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2019 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, University of Zagreb, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:131:347107 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-25 Repository / Repozitorij: ODRAZ - open repository of the University of Zagreb Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Sveučilište u Zagrebu Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za anglistiku Akademska godina 2018./2019. Marija Kozjak Utjecaj engleskog jezika na hrvatski hip-hop jezik Diplomski rad Mentor: dr.sc. Anđel Starčević, doc. Zagreb, 2019 University of Zagreb Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of English Academic Year 2018/2019 Marija Kozjak The Influence of English on Croatian Hip-hop Language Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Anđel Starčević Zagreb, 2019 Contents: 1 Abstract....................................................................................................................................5 2 Introduction..............................................................................................................................6 3 Hip-hop culture........................................................................................................................7 3.1 Hip-hop culture in Croatia.........................................................................................8 -

Popular Music and Political Change in Post- Tuñman Croatia Dr Catherine

‘It’s all the same, only he’s not here’?: popular music and political change in post- Tuñman Croatia Dr Catherine Baker University of Southampton Abstract: While Franjo Tuñman was the president of Croatia (1990–99), popular music and other forms of entertainment were heavily structured around the key presidential narratives: Croatia’s political and cultural independence from Yugoslavia, and the idea that Croatia’s war effort had been purely defensive. After Tuñman, the Croatian music industry had to cope with media pluralism and the transnational challenges of the digital era. Patriotic popular music expressed an oppositional narrative of Euroscepticism and resistance to the Hague Tribunal, yet Croatia retained and expanded its position in the transnational post-Yugoslav entertainment framework, undermining a key element of Tuñman’s ideology. ‘It’s all the same, only he’s not here’?: popular music and political change in post- Tuñman Croatia In September 2002, after another summer of protests against the government extraditing Croatian generals to the Hague Tribunal, the musician Marko Perković Thompson opened his concert at the Poljud stadium in Split by projecting a video which featured himself, the singer Ivan Mikulić and the Slavonian tamburica ensemble Najbolji hrvatski tamburaši. 1 The song, called ‘Sveto tlo hrvatsko’ (‘Holy Croatian soil’), lauded the late Croatian president Franjo Tuñman, who had died in December 1999. The men sang of Tuñman’s achievements and the sudden appearance of critics who had not dared to defy him when he was alive, and Thompson, a veteran of the Homeland War, contributed a verse remembering the days when friend had stood together with friend to defend Croatia. -

Race and the Yugoslav Region THEORY for a GLOBAL AGE

CATHERINE BAKER AND THE POOSTSSOOCICIALA ISST,T, PPOSSTT-CONNFFLLICCT,T POPOSTS COOLOLONNIIALA ? Race and the Yugoslav region THEORY FOR A GLOBAL AGE Series Editor: Gurminder K. Bhambra, Professor of Postcolonial and Decolonial Studies in the School of Global Studies, University of Sussex Globalization is widely viewed as a current condition of the world, but there is little engagement with how this changes the way we understand it. The Theory for a Global Age series addresses the impact of globalization on the social sciences and humanities. Each title will focus on a particular theoretical issue or topic of empirical controversy and debate, addressing theory in a more global and interconnected manner. With contributions from scholars across the globe, the series will explore different perspectives to examine globalization from a global viewpoint. True to its global character, the Theory for a Global Age series will be available for online access worldwide via Creative Commons licensing, aiming to stimulate wide debate within academia and beyond. Previously published by Bloomsbury: Published by Manchester University Press: Connected Sociologies Gurminder K. Bhambra Debt as Power Tim Di Muzio and Richard H. Robbins Eurafrica: The Untold History of European Integration and Colonialism Subjects of modernity: Time-space, Peo Hansen and Stefan Jonsson disciplines, margins Saurabh Dube On Sovereignty and Other Political Delusions Frontiers of the Caribbean Joan Cocks Phillip Nanton Postcolonial Piracy: Media Distribution John Dewey: The Global -

Februar 2021

DATUM URA ODDAJA NASLOV IZVAJALEC AVTORJI ¬AS MEDIJ ćTEVILKA ZALO¦BA 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP NE JOČI D‐DUR / / / 00:03:38 AAT 79849 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP OBJEMI ME SEKSTAKORD, ANSAMBEL TOVORNIK, PETER / PASARIČ, DAMJAN / TOVORNIK, PETER / 00:03:15 CDA CDN001685 SAMOZALOŽBA 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP LJUBIM TE SLOVENIJA ZELENA ALPSKI KVINTET / / / 00:03:42 DAL 78342 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP RAD BI JO VIDEL (VALČEK) AKORDI, ANSAMBEL ŠVAB, ROK / POŽEK, FANIKA / ŠVAB, ROK / 00:02:46 CDA CDN001279 RTV SLOVENIJA ZALOŽBA KASET IN PLOŠČ 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP NOCOJ POGLEJ V NEBO PAJDAŠI SLAK, LOJZE / POŽEK, FANIKA / ZLOBKO, NIKO / 00:03:18 DAL 47149 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP S TABO GEDORE / / / 00:03:51 DAL 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP OLIVIA PANČUR, NEŽA / / / 00:03:37 DAL 82220 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP KJE SVA OSTALA MARENTIČ, MATIC / / / 00:03:19 DAL 77033 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP DALEČ OD OČI KARRA / / / 00:03:39 DAL 77032 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP GOODBYE AMAYA / / / 00:03:27 DAL 82215 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP KJE SO PUNCE ANSAMBEL ŠENTJANCI, ANSAMBEL ŠENTJANCI / / / 00:02:22 DAL 72078 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP KAKO BI TI POVEDALA ŠEPET, ANSAMBEL / / / 00:02:43 DAL 72079 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP NORO ZALJUBLJEN SEM STIL, ANSAMBEL / / / 00:02:36 DAL 72077 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP NAZAJ ZA POL STOLETJA OPOJ, ANSAMBEL / / / 00:03:51 DAL 76311 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP GENERACIJA NEBA BATISTA CADILLAC / / / 00:04:11 DAL 81000 1.02.2016 00:00 NOČNI‐SNOP LJUBEZEN DAJE MOČ ANA IN JERNEJ / / / 00:04:09 DAL 78225 1.02.2016 -

Serbian Jerusalem: Religious Nationalism, Globalization and the Invention of a Holy Land in Europe's Periphery, 1985-2017

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 37 Issue 6 Article 3 2017 Serbian Jerusalem: Religious Nationalism, Globalization and the Invention of a Holy Land in Europe's Periphery, 1985-2017 Vjekoslav Perica University of Rijeka Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Perica, Vjekoslav (2017) "Serbian Jerusalem: Religious Nationalism, Globalization and the Invention of a Holy Land in Europe's Periphery, 1985-2017," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 37 : Iss. 6 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol37/iss6/3 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SERBIAN JERUSALEM: RELIGIOUS NATIONALISM, GLOBALIZATION AND THE INVENTION OF A HOLY LAND IN EUROPE’S PERIPHERY, 1985-2017 By Vjekoslav Perica Vjekoslav Perica is the author of Balkan Idols: Religion and Nationalism in Yugoslav States and a number of other scholarly publications. His most recent book, Pax Americana in the Adriatic and the Balkans, 1919-2014, was published in 2015 in Zagreb, Croatia. Perica obtained a PhD in history from the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, served as a U.S. Fulbright scholar in Serbia and held research fellowships at the United States Institute of Peace, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences, and Columbia University’s Institute for the Study of Human Rights. -

Motrista 95 Web

95 časopis za kulturu, znanost i društvena pitanja • svibanj - lipanj 2017 • issn 1512-5475 Časopis Motrišta referiran je u Central and Eastern European Online Library /Frankfurt am Main/ - http://www.ceeol.com Miro Petrović, Mato Tadić, Zvonko Kusić, Ljerka Ostojić, Jakov Pehar i Zdenko Ostojić Promocija knjige Mate Tadića u HAZU Zagreb Nova knjiga Mate Tadića pod nazivom Ustavnopravni položaj Hrvata u Bosni i Hercegovini (izdanje Hrvatske akademije za znanost i umjetnost u BiH), predstavljena je u ponedjeljak 26. lipnja 2017. godine u Hrvatskoj aka- demiji znanosti i umjetnosti u Zagrebu, u velikoj dvora- Andrić, Antunović-Skelo, ni Akademije na Trgu Nikole Šubića Zrinskog. Bebek-Ivanković, Beljan Kovačić, Bio je to, ujedno, i prvi službeni susret dviju hrvatskih Brkić Milinković, Crnić, Akademija iz dviju država – BiH i RH. Curić I., Curić S., Grgić, Grubišić, Karačić, Ljevak, Pozdravne riječi nazočnima uputili su predsjednici Lovrenović, Lovrić, Marić, Akademija Zvonko Kusić i Jakov Pehar te Ljerka Osto- Mulić, Nedić, Papić, Pehar, jić. O knjizi su govorili Mato Arlović, Ivo Lučić, Josip Mu- Stanić, Stojić, Škarica selimović i autor Mato Tadić. Jakov Pehar, Josip Muselimović i Zdenko Ostojić 95 br. 95, časopis za kulturu, znanost i društvena pitanja Utemeljitelj i nakladnik: Matica hrvatska Mostar Sunakladnik: Hrvatska akademija za znanost i umjetnost u Bosni i Hercegovini Realizacija i distribucija: Zdravo društvo Mostar Za nakladnike: Ljerka OSTOJIĆ i Jakov PEHAR Glavni urednik: Josip MUSELIMOVIĆ Odgovorna urednica: Ljerka OSTOJIĆ Tajnica: Vanja PRUSINA Uredništvo: Mladen BEVANDA, Misijana BRKIĆ MILINKOVIĆ, fra Ante MARIĆ, Dragan MARIJANOVIĆ, Šimun MUSA, Mira PEHAR, Božo ŽEPIĆ Lektura i korektura: Misijana BRKIĆ MILINKOVIĆ Grafičko oblikovanje: SHIFT kreativna agencija, Mostar Telefon/faks: +387 36 323 501 E-mail: [email protected] Adresa: Ulica kralja Zvonimira b.b., 88000 Mostar Žiroračuni: 338 100 220 201 2542 UniCredit Bank d.d.