Preaching Reconciliation: a Study of the Narratives in Genesis 37-50

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZENITHBANK-Opt-1.Pdf

USING YOUR STUDY PACK Use the table of content to guide your study. This study pack is for personal use only. Please note: Sensitive order and payment details are automatically embedded on your study pack. For your security, Please, Do not share. You are entitled to one year of update. To get it, Create account at teststreams.com/my-account to get any new update. CONTENT GUIDE PAGE 2 --------------------QUANTITATIVE REASONING 1 PAGE 114 ---------------VERBAL REASONING 1 PAGE 175 ---------------GENERAL KNOWLEDGE PAGE 405 -------------- TEST OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE PAGE 425 -------------- QUANTITATIVE REASONING 2 PAGE 453 -------------- VERBAL REASONING 2 Page 1 SECTION1: QUANTITATIVE REASONING 1. If I give you seven apples, you will then have five times as many as I would then have, however, if you give me seven apples, we will then both have the same number of apples. How many apples do we currently have? A. I have 24 apples and you have 18 apples. B. I have 10 apples and you have 32 apples. C. I have 18 apples and you have 24 apples. D. I have 14 apples and you have 28 apples. E. I have 12 apples and you have 20 apples. The correct answer is option [D] 2. If it takes Seyi twenty minutes to boil an egg in 1.5 litres of water, how long will it take Ala who is 3 years older than Seyi to boil 4 eggs in 1.5 litres of water? A. 10 minutes B. 20 minutes C. 25 minutes D. 5 minutes E. 80 minutes The correct answer is option [B] 3. -

The Judiciary and Nigeria's 2011 Elections

THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS CSJ CENTRE FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE (CSJ) (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS Written by Eze Onyekpere Esq With Research Assistance from Kingsley Nnajiaka THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiii First Published in December 2012 By Centre for Social Justice Ltd by Guarantee (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) No 17, Flat 2, Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, P.O. Box 11418 Garki, Abuja Tel - 08127235995; 08055070909 Website: www.csj-ng.org ; Blog: http://csj-blog.org Email: [email protected] ISBN: 978-978-931-860-5 Centre for Social Justice THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiiiiii Table Of Contents List Of Acronyms vi Acknowledgement viii Forewords ix Chapter One: Introduction 1 1.0. Monitoring Election Petition Adjudication 1 1.1. Monitoring And Project Activities 2 1.2. The Report 3 Chapter Two: Legal And Political Background To The 2011 Elections 5 2.0. Background 5 2.1. Amendment Of The Constitution 7 2.2. A New Electoral Act 10 2.3. Registration Of Voters 15 a. Inadequate Capacity Building For The National Youth Service Corps Ad-Hoc Staff 16 b. Slowness Of The Direct Data Capture Machines 16 c. Theft Of Direct Digital Capture (DDC) Machines 16 d. Inadequate Electric Power Supply 16 e. The Use Of Former Polling Booths For The Voter Registration Exercise 16 f. Inadequate DDC Machine In Registration Centres 17 g. Double Registration 17 2.4. Political Party Primaries And Selection Of Candidates 17 a. Presidential Primaries 18 b. -

Southern Kaduna: Democracy and the Struggle for Identity and Independence by Non-Muslim Communities in Northern Nigeria 1999- 2011

Presented at the 34th AFSAAP Conference Flinders University 2011 M. D. Suleiman, History Department, Bayero University, Kano Southern Kaduna: Democracy and the struggle for identity and Independence by Non-Muslim Communities in Northern Nigeria 1999- 2011 ABSTRACT Many non- Muslim communities were compelled to live under Muslim administration in both the pre-colonial, colonial and post colonial era in Nigeria While colonialism brought with it Christianity and western education, both of which were employed by the non-Muslims in their struggle for a new identity and independence, the exigencies of colonial administration and post- independence struggle made it difficult for non-Muslim communities to fully assert their independence. However, Nigeria’s new democratic dispensation ( i.e. Nigeria’s third republic 1999-to 2011 ) provided great opportunities and marked a turning point in the fortune of Southern Kaduna: first, in his 2003-2007 tenure, Governor Makarfi created chiefdoms ( in Southern Kaduna) which are fully controlled by the non-Muslim communities themselves as a means of guaranteeing political independence and strengthening of social-political identity of the non-Muslim communities, and secondly, the death of President ‘Yar’adua led to the emergence and subsequent election of Governor Patrick Ibrahim Yakowa in April 2011 as the first non-Muslim civilian Governor of Kaduna State. How has democracy brought a radical change in the power equation of Kaduna state in 2011? INTRODUCTION In 1914, heterogeneous and culturally diverse people and regions were amalgamated and brought together into one nation known as Nigeria by the British colonial power. In the next three years or so therefore, i.e., in 2014, the Nigerian nation will be one hundred years old. -

Six Years of Existence of Tsangaya Schools in Kaduna State (2010-2016): an Assessment

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-3 | Issue-1| Jan-Feb 2021 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2021.v03i01.001 Research Article Six Years of Existence of Tsangaya Schools in Kaduna State (2010-2016): An Assessment Sulaiman Salisu Muhammad* Department of Nigerian Languages and Linguistics Kaduna State University Abstract: This research is an assessment of the six years of existence of “Tsangaya Article History Schools” in Kaduna state, Nigeria. The research centers on ascertaining the achievements Received: 21.12.2020 recorded since after the implementation of the tsangaya schools. Accordingly, the research Accepted: 06.01.2021 investigates the challenges facing the implementation processes. The methodology adopted Published: 09.01.2021 in the research is a direct interview. The tsangaya schools are visited to obtain primary data Journal homepage: on the implementation status as well as the nature of running the affairs of the schools. https://www.easpublisher.com Accordingly, statistical data about the school is obtained from Federal and State Ministries of Education. The research found that there are thirty-five Quranic schools under the Quick Response Code program across the state. Also, there has been an effort to integrate formal education in such schools. The research learned that, among others, problems surrounding the program include inadequate staffing, inadequate funding, and an unconducive learning environment. Keywords: Tsangaya Schools; Almajiri; Kaduna State; Implementation; Education. Copyright © 2021 The Author(s): This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium for non-commercial use provided the original author and source are credited. -

1 Godfatherism and Credible Primary Elections in Nigeria

GODFATHERISM AND CREDIBLE PRIMARY ELECTIONS IN NIGERIA:A STUDY OF 2015 GUBERNATORIAL PRIMARIES OF PEOPLES DEMOCRATIC PARTY (PDP) IN KADUNA STATE MUHAMMAD, Aminu Kwasau Ph.D Department of Political Science, Faculty of Social Sciences, Kaduna State University,Kaduna Abstract The Conduct of 2015 Gubernatorial Primaries by the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) in Kaduna State has been marred by irregularities and flaws. The improper conduct of this important segment of internal democracy became a great challenge facing the party which has its root from the zero sum nature of politics in the state, godfatherism, money politics, powerful influence of elite, incumbency factor, exclusiveness of rank-and-file members in Party Primaries and infact; this has left in its wake wanton destruction of party ideology, democratic practices and values, lives and properties. The study examines the nature, character and dynamics of 2015 PDP Gubernatorial Primaries in Kaduna state. The research adopted the Elite Theory in the analysis of godfather politics in Nigeria. The researcher made use of the multi-stage sampling technique to get the population of the study. The State was clustered into three (3) senatorial zones from where two (2) Local Government Areas were selected from each. From these, the Adhoc delegates were systematically selected for the interview. Data was presented using simple percentage statistical method. The interpretation of the analyzed data as it related to the objectives of the study was presented in a tabular form.Finally, the research has been able to find out that, there was no internal democracy in Kaduna state chapter of Peoples Democratic Party between 1999-2015 as a result of some major challenges that are identified as follows; godfatherism, money politics, influence of powerful elite, incumbency factor, neglecting rank-and-file members in most decisions affecting party primaries, the application of federal character principles, rural-cosmopolitan politics and ethno-religious factor. -

Nigeria's 2011 Elections

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE PEACEBrIeF103 United States Institute of Peace • www.usip.org • Tel. 202.457.1700 • Fax. 202.429.6063 August 15, 2011 DORINA BEKOE Nigeria’s 2011 Elections: Best Run, E-mail: [email protected] but Most Violent Summary • Nigeria’s 2011 general election received high praise for being well-managed. But post-election violence claimed 800 lives over three days in northern Nigeria and displaced 65,000 people, making the elections the most violent in Nigeria’s history. • The violence was triggered by a belief that challenger Muhammadu Buhari, a northerner, should have won the election. • Two special commissions established to examine the factors leading to the violence will have limited effect in breaking the cycle of violence unless their reports lead to ending impunity for political violence. In addition, local peacemaking initiatives and local democratic institutions must be strengthened. The Well-Managed 2011 Elections Nigeria’s 2011 general elections—in particular the presidential election—were seen widely as being well-run. This was especially important given the universally decried elections of 2007.1 A number of factors contributed to ensuring that Nigeria’s 2011 elections were successfully Only such a significant administered. They include the fact that the voters’ register was the most accurate, and there was “break from the past can also adequate training and fielding of election observers. The chair of the Independent Nigerian help Nigeria move toward Electoral Commission (INEC), Attahiru Jega, was well regarded and judged independent from the government. And, the parallel vote tabulation used by domestic observers allowed poll monitors realizing the fruits of a well- to concurrently record the results of the election along with INEC as a means to provide a check organized and administered on the official results. -

M Sletter 1 Maiden Edition Vo I ~ No....: 1 March 2O13

Arewa Research & Development Project M sletter 1 Maiden Edition Vo I ~ No....: 1 March 2o13 .. ' • i I t l '4 , , I • 1 • \l r 1 • I • ~ 4 1 .. .,. ' t ' 1: it t lf' . Re$1~ r 4Setl Pre$8 · ' ·Pf\ ~ · ; I!'.~: l;; ;! ~ dil!i!i I!, j j); lliilliiiilllllllllllll jj II ! • • AGRICULTURE ~. EDUCATION • H EALirf~ ~ ;. ENERGY • MINERAL!J RESOURCES I ',; i • • SKILL ACQUISITION & PROMOTION OF SCIENCE & TEChtNOLOGY ---~·· fl_'p' ' I . r . ~~r·'t:l EDITORIAL . ' ----taoleofcontents---- Editor ~ in - Ch i ef 1. From the Editior-in-Chief ................ ·_. ___ . _. 2 Dr. Kabiru S. Chafe Executive Assistant 2. Mission and Vision of ARDP. ... _. __ .. _... _....... _ 2 Mal. Usman Suleiman 3. Address by Prof. Abdulla hi Mustapha Vice Chancellor, A.B.U, Zaria __ . _. _....... _.... _.... 4 EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. Usman Bugaje 4. Address by the Chief Host, His Excellency Chairman Late Governor Patrick I. Yakowa, CON_ .•••• • .... _ .• _ • . 6 Dr. Yima Sen Member 5. Our Wealth of Mineral Resources Prof. Abdullahi M. Ashafa Member by Prof. Ibrahim Garba ...... .. _.... ___ . 8 Prof. Nuhu Obaje 6. Politics and Security in the North Member By Prof. Kyari Mohammed .. _. _..... _.... __ . _____ 11 Hajiya Rabi Adamu Eshak Member 7. Energy Sources & Sustainable Development of the North .. By Prof. E.J. Bala & Dr. G.Y. Pam ....... _. _. ______ 13 Mal. Isa Modibbo Member 8. Universal Basic Education in Northern Nigeria Mr. G.S. Pwul, SAN By Prof. Gidado Tahir. ........ _. 16 Member 9. Security, Politics & Economy of the North By Dr. Hakeem Baba-Ahmed_ . _. _. -

NDDC SCHOLARSHIP PAST QUESTIONS PACK Law Before You Begin

I , l ,.b � I NDDC SCHOLARSHIP PAST QUESTIONS PACK lAW Before you begin: Please note that this study pack contains past uestions from to .The pack also covers all discipline specific uestions. If however you did not find your course listed you can either send us a on instagram teststreams chat with us live on our websitewww.teststreams.com or send an email to supportteststreams.com. NAVIGATION: In order to easily navigate through this pack you need to access the table of content on the menu. • For mobile devices: Tap on your phone/tablet screen to reveal the menu. Click the Table of content" section on the display menu. • For Computers: The Table of Content menu is displayed on the left. You can just click on any topic to start reading. Should we find any further information that will think will aid your success in this test trust we will send it to you for free. astly information is power. Ensure you dont miss out on any further updates please follow us on instagram.com/testststreams. e reply instagram messages swiftly. Thanks for using teststreams studypacks to prepare. All the best. Title page i Table of content ii About the NDDC Scholarship test iii A L AW A L A AW CINFORES QUESTIONS LAW bot C cola Te C cola an annal cola oane b te e elta eeloent Coon t offee to bot ate an ean tent fo e elta eon to t n electe nete aboa Te elble tate ncle a bo tate eela tate Co e tate elta tate tate o tate an e tate ettn ea fo te cola at t not ee tat o ae an aon n an oeea net befoe o al C at lbet to c a cool fo o f offee -

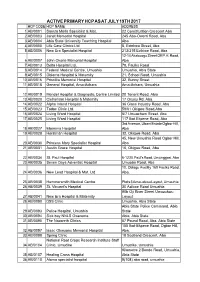

ACTIVE PRIMARY HCP AS at JULY 19TH 2017 HCP CODE HCP NAME ADDRESS 1 AB/0001 Sancta Maria Specialist & Mat

ACTIVE PRIMARY HCP AS AT JULY 19TH 2017 HCP CODE HCP NAME ADDRESS 1 AB/0001 Sancta Maria Specialist & Mat. 22 Constitutition Crescent Aba 2 AB/0003 Janet Memorial Hospital 245 Aba-Owerri Road, Aba 3 AB/0004 Abia State University Teaching Hospital Aba 4 AB/0005 Life Care Clinics Ltd 8, Ezinkwu Street, Aba 5 AB/0006 New Era Specialist Hospital 213/215 Ezikiwe Road, Aba 12-14 Akabuogu Street Off P.H. Road, 6 AB/0007 John Okorie Memorial Hospital Aba 7 AB/0013 Delta Hospital Ltd. 78, Faulks Road 8 AB/0014 Federal Medical Centre, Umuahia Umuahia, Abia State 9 AB/0015 Obioma Hospital & Maternity 21, School Road, Umuahia 10 AB/0016 Priscillia Memorial Hospital 32, Bunny Street 11 AB/0018 General Hospital, Ama-Achara Ama-Achara, Umuahia 12 AB/0019 Mendel Hospital & Diagnostic Centre Limited 20 Tenant Road, Abia 13 AB/0020 Clehansan Hospital & Maternity 17 Osusu Rd, Aba. 14 AB/0022 Alpha Inland Hospital 36 Glass Industry Road, Aba 15 AB/0023 Todac Clinic Ltd. 59/61 Okigwe Road,Aba 16 AB/0024 Living Word Hospital 5/7 Umuocham Street, Aba 17 AB/0025 Living Word Hospital 117 Ikot Ekpene Road, Aba 3rd Avenue, Ubani Estate Ogbor Hill, 18 AB/0027 Ebemma Hospital Aba 19 AB/0028 Horstman Hospital 32, Okigwe Road, Aba 45, New Umuahia Road Ogbor Hill, 20 AB/0030 Princess Mary Specialist Hospital Aba 21 AB/0031 Austin Grace Hospital 16, Okigwe Road, Aba 22 AB/0034 St. Paul Hospital 6-12 St. Paul's Road, Umunggasi, Aba 23 AB/0035 Seven Days Adventist Hospital Umuoba Road, Aba 10, Oblagu Ave/By 160 Faulks Road, 24 AB/0036 New Lead Hospital & Mat. -

Agricultural Econs-Opt

Before you begin: Please note that this study pack contains past uestions from to .The pack also covers all discipline specific uestions. If however you did not find your course listed you can either send us a on instagram teststreams chat with us live on our websitewww.teststreams.com or send an email to supportteststreams.com. NAVIGATION: In order to easily navigate through this pack you need to access the table of content on the menu. • For mobile devices: Tap on your phone/tablet screen to reveal the menu. Click the Table of content" section on the display menu. • For Computers: The Table of Content menu is displayed on the left. You can just click on any topic to start reading. Should we find any further information that will think will aid your success in this test trust we will send it to you for free. astly information is power. Ensure you dont miss out on any further updates please follow us on instagram.com/testststreams. e reply instagram messages swiftly. Thanks for using teststreams studypacks to prepare. All the best. Title page i Table of content ii About the NDDC Scholarship test iii 0AER E ANSWER KEYS 0AER E 9 0AER 30 ANSWER KEYS 49 CINFORES QUESTIONS ARENS bot C cola Te C cola an annal cola oane b te e elta eeloent Coon t offee to bot ate an ean tent fo e elta eon to t n electe nete aboa Te elble tate ncle a bo tate eela tate Co e tate elta tate tate o tate an e tate ettn ea fo te cola at t not ee tat o ae an aon n an oeea net befoe o al C at lbet to c a cool fo o f offee te cola a oenent fne -

Nigeria's 2011 Elections: Best Run, but Most Violent

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE PEACEBrIeF103 United States Institute of Peace • www.usip.org • Tel. 202.457.1700 • Fax. 202.429.6063 August 15, 2011 DORINA BEKOE Nigeria’s 2011 Elections: Best Run, E-mail: [email protected] but Most Violent Summary • Nigeria’s 2011 general election received high praise for being well-managed. But post-election violence claimed 800 lives over three days in northern Nigeria and displaced 65,000 people, making the elections the most violent in Nigeria’s history. • The violence was triggered by a belief that challenger Muhammadu Buhari, a northerner, should have won the election. • Two special commissions established to examine the factors leading to the violence will have limited effect in breaking the cycle of violence unless their reports lead to ending impunity for political violence. In addition, local peacemaking initiatives and local democratic institutions must be strengthened. The Well-Managed 2011 Elections Nigeria’s 2011 general elections—in particular the presidential election—were seen widely as being well-run. This was especially important given the universally decried elections of 2007.1 A number of factors contributed to ensuring that Nigeria’s 2011 elections were successfully Only such a significant administered. They include the fact that the voters’ register was the most accurate, and there was “break from the past can also adequate training and fielding of election observers. The chair of the Independent Nigerian help Nigeria move toward Electoral Commission (INEC), Attahiru Jega, was well regarded and judged independent from the government. And, the parallel vote tabulation used by domestic observers allowed poll monitors realizing the fruits of a well- to concurrently record the results of the election along with INEC as a means to provide a check organized and administered on the official results. -

Overview of Structure of Healthcare in Nigeria and New Born Screening

ARISE TRAIN-THE-TRAINER WORKSHOP. WORKSHOP FOCUS: LABORATORY SKILLS. 11TH-13TH SEPTEMBER, 2019 AT REIZ INTERCONTINENTAL HOTEL, ABUJA, NIGERIA. OVERVIEW OF STRUCTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN NIGERIA AND NEW BORN SCREENING AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OVERVIEW OF STRUCTURE OF HEALTHCARE IN NIGERIA AND NEW BORN SCREENING AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Presenter; DR. GAJERE GYAWIYA JONATHAN KADUNA STATE MINISTRY OFHEALTH DEPARTMENT OF MEDICAL SERVICES Outline Introduction Levels of Health Care Deliveries Healthcare financing Health Management Information system (HMIS) New-born screening Challenges Conclusion Nigerian population pyramid-2017 Human resource and population NIGERIA USA Introduction……………..2018 budget Budget for 2018 Introduction Nigeria is the 7th most populated country . Estimated to have 200.96 million people according to the world population review-2019 Has 36 states + the FCT 774 Local Government Areas Has numerous disease burdens Life expectancy for males and females are 53.7% and 55.4% respectively Introduction 68.5% of the population have access to clean Literacy rate is estimated at 59.6% but varies from one region of the country to another. The country has over 250 ethnic groups and more than 500 languages Over 50% of the population are youths Levels of care There are three main levels of Health care in addition to the Private sector. I. Primary Healthcare Centres: The first level of contact of individuals, families and communities with the national health system. Health education, preventive, prenatal, emergency and basic health care services for remote rural areas. (Alma Ata Declaration of 1978). II. Secondary Health Facilities: Serves as referral centres for cases requiring more advanced care III. Tertiary Health Institutions: More complex cases are referred for specialized care.