Evolving Paradigms for Regulating Consumer Credit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

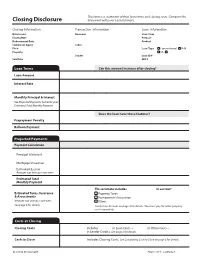

Closing Disclosure Document with Your Loan Estimate

This form is a statement of final loan terms and closing costs. Compare this Closing Disclosure document with your Loan Estimate. Closing Information Transaction Information Loan Information Date Issued Borrower Loan Term Closing Date Purpose Disbursement Date Product Settlement Agent Seller File # Loan Type Conventional FHA Property VA _____________ Lender Loan ID # Sale Price MIC # Loan Terms Can this amount increase after closing? Loan Amount Interest Rate Monthly Principal & Interest See Projected Payments below for your Estimated Total Monthly Payment Does the loan have these features? Prepayment Penalty Balloon Payment Projected Payments Payment Calculation Principal & Interest Mortgage Insurance Estimated Escrow Amount can increase over time Estimated Total Monthly Payment This estimate includes In escrow? Estimated Taxes, Insurance Property Taxes & Assessments Homeowner’s Insurance Amount can increase over time Other: See page 4 for details See Escrow Account on page 4 for details. You must pay for other property costs separately. Costs at Closing Closing Costs Includes $5,877.00 in Loan Costs + $7,642.43 in Other Costs – $0 in Lender Credits. See page 2 for details. Cash to Close Includes Closing Costs. See Calculating Cash to Close on page 3 for details. CLOSING DISCLOSURE PAGE 1 OF 5 • LOAN ID # 0000000000 This form is a statement of final loan terms and closing costs. Compare this Closing Disclosure document with your Loan Estimate. Closing Information Transaction Information Loan Information Date Issued Borrower Loan Term -

5/1 MOP Loan Program

GENERAL GUIDELINES 5/1 Maximum Loan-to-Value Ratio: Same as Standard MOP LTV Thresholds Fixed Rate Period: 5 Years ORTGAGE M Maximum Loan Term: 30 Years RIGINATION Qualifying Interest Rate: Initial 5/1 MOP Interest Rate O Minimum Interest Rate: 3.25% ROGRAM P Maximum Payment-to-Income Ratio: 40% Maximum Overall Debt-to-Income Ratio: 48% PROGRAM OVERVIEW 5/1 MOP Initial Interest Rate The 5/1 Mortgage Origination Program (5/1 MOP) loan is a fully-amortizing mortgage loan The initial fixed interest rate* in effect during the Fixed Rate that offers an initial fixed interest rate and payment for the first 5 years of the loan, after which Period of the loan is comprised of the following three (3) the loan converts to a 1-year adjustable rate mortgage (“Standard MOP”) for the remaining components: loan term. The maximum overall loan term is 30 years. All or any portion of the principal Index: 5-year Treasury Bond Yield balance may be prepaid without penalty at any time and there is no negative amortization associated with 5/1 MOP loans. For eligibility requirements, refer to the MOP Brochure. Spread: J.P. Morgan U.S. Liquid Index (JULI) Index Service Fee: .25% IMPORTANT CONSIDERATIONS: *The minimum 5/1 MOP Initial Interest Rate is 3.25% • The 5/1 MOP Initial Interest Rate may be higher or lower than the current Standard Rate offered for a Standard MOP loan. The current interest rate for each of these loan products is available at www.ucop.edu/loan-programs. QUESTIONS? • Fixed rate payments during the first 5 years of the loan provide a stable monthly payment Contact the local Campus Housing Programs to borrowers; however, there is potential for increased monthly payments when the Fixed Representative or the University of California Home Loan Rate Period ends. -

Agency Guideline Revisions Note: Suntrust Mortgage Specific Overlays Are Underlined

Agency Guideline Revisions Note: SunTrust Mortgage specific overlays are underlined. Impacted Revised Guidelines Topic Impacted Products Current Guidelines Document Effective Immediately for NEW AND EXISTING Loan Applications ON OR After May 26, 2017 Appraisal Correspondent HomeReady® Appraisal Analysis: Agency Loan Programs / Improvements Section of the Appraisal Report Appraisal Analysis: Agency Loan Programs / Improvements Section of the Appraisal Report Requirements Section 1.07 Mortgage / Accessory Appraisal- (non-AUS & Non-AUS Non-AUS Units Guideline DU) Note: Below is an EXCERPT only of the guidance from the above referenced section. All other currently published Note: Below is an EXCERPT only of the guidance from the above referenced section. All other currently published Home guidelines from this section remain the same. guidelines from this section remain the same. Possible® Accessory Units Accessory Units Mortgage Fannie Mae will purchase a one-unit property with an accessory unit. An accessory unit is typically an Fannie Mae will purchase a one-unit property with an accessory unit. An accessory unit is typically an (LPA) additional living area independent of the primary dwelling unit, and includes a fully functioning additional living area independent of the primary dwelling unit, and includes a fully functioning kitchen and bathroom. Some examples may include a living area over a garage and basement units. kitchen and bathroom. Some examples may include a living area over a garage and basement units. Whether a property is defined as a one-unit property with an accessory unit or a two-unit property Whether a property is defined as a one-unit property with an accessory unit or a two-unit property will be based on the characteristics of the property, which may include, but are not limited to, the will be based on the characteristics of the property, which may include, but are not limited to, the existence of separate utilities, a unique postal address, and whether the unit is rented. -

Adjustable-Rate Mortgage (ARM) Is a Loan with an Interest Rate That Changes

The Federal Reserve Board Consumer Handbook on Adjustable-Rate Mortgages Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System www.federalreserve.gov 0412 Consumer Handbook on Adjustable-Rate Mortgages | i Table of contents Mortgage shopping worksheet ...................................................... 2 What is an ARM? .................................................................................... 4 How ARMs work: the basic features .......................................... 6 Initial rate and payment ...................................................................... 6 The adjustment period ........................................................................ 6 The index ............................................................................................... 7 The margin ............................................................................................ 8 Interest-rate caps .................................................................................. 10 Payment caps ........................................................................................ 13 Types of ARMs ........................................................................................ 15 Hybrid ARMs ....................................................................................... 15 Interest-only ARMs .............................................................................. 15 Payment-option ARMs ........................................................................ 16 Consumer cautions ............................................................................. -

Iowa Title Guaranty Commercial Application

Iowa Title Guaranty Commercial Application Property Address: _________________________________ Coverage Type and Amount of Requested Coverage: _________________________________ Owner $________________ Summary of Transaction / Possible Issues: Lender - First $________________ _________________________________ Lender - Second $________________ _________________________________ Note: A cancellation fee of up to 10% of the premium charge can be assessed Type of Property: Documents Attached: Commercial Industrial Preliminary Title Opinion Final Title Opinion Agricultural Bare Land Premium Check (Payable to Iowa Title Guaranty) Multifamily Wetlands Composite Mortgage Affidavit Survey Owner/General Contractor Sworn Statement Mechanic Lien Waivers Other Information: Other: Mortgage (purchase) Cash Transaction Refinance Installment Contract Applicant Contact Information: Construction Loan Rental Property Name: _________________________________ End Loan Leasehold Company: ______________________________ Phone: _________________________________ Buyer(s) / Borrower(s): Email: _________________________________ _________________________________ Fax: ___________________________________ _________________________________ Contacts at Iowa Title Guaranty Commercial: Seller(s): Matt Veldey [email protected] _________________________________ Phone: 515.452.0490 _________________________________ Ethan Murray Lender – Name and Address: [email protected] Phone: 515.452.0483 _________________________________ _________________________________ -

Chapter 3. the VA Loan and Guaranty Overview

VA Pamphlet 26-7, Revised Chapter 3: The VA Loan and Guaranty Chapter 3. The VA Loan and Guaranty Overview In this Chapter This chapter contains the following topics. Topic Topic Name See Page 1 Basic Elements of a VA-Guaranteed Loan 3-2 2 Eligible Loan Purposes 3-5 3 Maximum Loan 3-7 4 Maximum Guaranty on VA Loans 3-10 5 Occupancy 3-12 6 Interest Rates 3-16 7 Discount Points 3-17 8 Maturity 3-19 9 Amortization 3-20 10 Eligible Geographic Locations for the Secured Property 3-22 11 What Does a VA Guaranty Mean to the Lender? 3-23 12 Post-Guaranty Issues 3-26 3-1 VA Pamphlet 26-7, Revised Chapter 3: The VA Loan and Guaranty 1. Basic Elements of a VA-Guaranteed Loan Change Date November 8, 2012, Change 21 • This section has been updated to remove a hyperlink and make minor grammatical edits. a. General rules The following table provides general rules and information critical to understanding a VA loan guaranty. Exceptions and detailed explanations have been omitted. Instead, a reference to the section in this handbook that addresses each subject is provided. Subject Explanation Section Maximum Loan VA has no specified dollar amount(s) for the “maximum 3 of this Amount loan.” The maximum loan amount depends upon: chapter • the reasonable value of the property indicated on the Notice of Value (NOV), and • the lenders needs in terms of secondary market requirements. Downpayment No downpayment is required by VA unless the purchase price 3 of this exceeds the reasonable value of the property, or the loan is a chapter Graduated Payment Mortgage (GPM). -

Consumer Handbook on Adjustable Rate Mortgages

CONSUMER HANDBOOK ON Adjustable-Rate Mortgages Find out how your payment can change over time An official publication of the U.S. government How to use the booklet How can this booklet help you? When you and your mortgage lender discuss This booklet can help you decide whether an adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs), you receive adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) is the right a copy of this booklet. When you apply for an choice for you and to help you take control of ARM loan, you receive a Loan Estimate. You can the homebuying process. request and receive multiple Loan Estimates from competing lenders to find your best deal. Your lender may have already provided you with a copy of Your Home Loan Toolkit. You You may want to have your Loan Estimate handy can also download the Toolkit from the CFPB’s for any loan you are considering as you work Buying a House guide at cfpb.gov/buy-a- through this booklet. We reference a sample house/. Loan Estimate throughout the booklet to help you apply the information to your situation. You can find more information about ARMs An ARM is a mortgage with an interest at cfpb.gov/about-arms. You’ll also find other rate that changes, or “adjusts,” mortgage-related CFPB resources, facts, and throughout the loan. tools to help you take control of the homebuying process. With an ARM, the interest rate and monthly payment may start out low. However, both the rate and the payment About the CFPB can increase very quickly. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Consider an ARM only if you can afford regulates the offering and provision of consumer increases in your monthly payment—even financial products and services under the federal to the maximum amount. -

County Commissioners Schedule Tuesday, July 14, 2020 Legislative Day

COUNTY COMMISSIONERS SCHEDULE TUESDAY, JULY 14, 2020 LEGISLATIVE DAY To comply with the Governor’s proclamation declaring a state of emergency in Maryland, to minimize the person-to-person spread of COVID-19, we encourage that citizens stay home and watch the County Commissioner’s meeting live on our QAC Website at qac.org/live or on QACTV’s Television channel on Atlantic Broadband cable (channel 7 or 77). To maintain social distancing, seating will be limited. If you have any respiratory symptoms such as fever, cough, and/or shortness of breath, please refrain from attending the meeting and notify a healthcare provider. We will be screening all meeting participants prior to entering the building. Press and Public Comments is encouraged. Please send your written comments to [email protected] or speak live by going to qac.org/publiccomment Thank you for your cooperation and understanding. 1. CLOSED SESSION 5:00 p.m. Todd Mohn, PE, County Administrator Beverly Churchill, Human Resources Director “Under Section 3-305b(1) of the General Prevision Article” “Personnel” “Boards/Commissions” 2. CALL TO ORDER 5:30 p.m. Call to Order, Pledge of Allegiance, Moment of Silence, Approval of Agenda Accept County Commissioners’ Minutes - Regular Minutes – June 23, 2020 - Roads Minutes – June 9, 2020 - Sanitary Minutes – May 26, 2020 - Closed Session – June 23, 2020 Press and Public Comments** 3. NEW BUSINESS 5:35 p.m. DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS Admin/Engineering/Property Management 1. Wetland Mitigation Delineation & Design: Contract Award 2. Property Management – Weed Control - FY21 Truck Solid Waste 3. Solid Waste Division – Groundwater and Landfill Gas Monitoring Contract Award Sanitary 4. -

Mortgage Loan Disclosure Statement / Good Faith Estimate

MORTGAGE LOAN DISCLOSURE STATEMENT – GOOD FAITH ESTIMATE NONTRADITIONAL MORTGAGE LOAN PRODUCT (ONE TO FOUR RESIDENTIAL UNITS (RE885) INFORMATIONAL SHEET WHEN TO USE THIS FORM NONTRADITIONAL LOAN PRODUCTS – THIS FORM MUST BE USED WHEN THE LOAN PRODUCT BEING OFFERED TO THE CONSUMER ALLOWS THE BORROWER TO DEFER REPAYMENT OF PRINCIPAL OR INTEREST AND IS SECURED BY A 1 TO 4 UNIT RESIDENTIAL PROPERTY WHETHER OWNER OR NON-OWNER OCCUPIED. Commissioner’s Regulation 2842 defines a nontraditional loan product as “a loan that allows borrowers to defer repayment of principal or interest. Such products include, but are not limited to, interest only loans where the borrower pays no loan principal for a period of time and payment option loans where one or more of the payment options may result in negative amortization. A “nontraditional loan product” does not include reverse mortgages or home equity lines of credit (other than simultaneous second lien loans).” If the loan product is NOT a nontraditional loan product the RE882 or RE883 form may be used. PROPERTY SECURING THE LOAN – This form is used only when the real property securing the nontraditional loan is a 1 to 4 unit residential property whether owner or non-owner occupied. When the property securing the loan is NOT a 1 to 4 unit residential property the RE882 or RE883 may be used. TIPS ON COMPLETING THIS FORM Page 1 – Compensation to Broker (Not Paid Out of Loan Proceeds) – This section is completed to disclose any compensation received by the broker from a lender in the form of a yield/spread premium, service release premium or any other rebate or compensation. -

Closing Disclosure Document with Your Loan Estimate

This form is a statement of final loan terms and closing costs. Compare this Closing Disclosure document with your Loan Estimate. Closing Information Transaction Information Loan Information Date Issued 4/15/2013 Borrower Michael Jones and Mary Stone Loan Term 30 years Closing Date 4/15/2013 123 Anywhere Street Purpose Purchase Disbursement Date 4/15/2013 Anytown, ST 12345 Product Fixed Rate Settlement Agent Epsilon Title Co. Seller Steve Cole and Amy Doe File # 12-3456 321 Somewhere Drive Loan Type x Conventional FHA Property 456 Somewhere Ave Anytown, ST 12345 VA _____________ Anytown, ST 12345 Lender Ficus Bank Loan ID # 123456789 Sale Price $180,000 MIC # 000654321 Loan Terms Can this amount increase after closing? Loan Amount $162,000 NO Interest Rate 3.875% NO Monthly Principal & Interest $761.78 NO See Projected Payments below for your Estimated Total Monthly Payment Does the loan have these features? Prepayment Penalty YES • As high as $3,240 if you pay off the loan during the first 2 years Balloon Payment NO Projected Payments Payment Calculation Years 1-7 Years 8-30 Principal & Interest $761.78 $761.78 Mortgage Insurance + 82.35 + — Estimated Escrow + 206.13 + 206.13 Amount can increase over time Estimated Total Monthly Payment $1,050.26 $967.91 This estimate includes In escrow? Estimated Taxes, Insurance x Property Taxes YES & Assessments $356.13 x Homeowner’s Insurance YES Amount can increase over time a month x Other: Homeowner’s Association Dues NO See page 4 for details See Escrow Account on page 4 for details. You must pay for other property costs separately. -

Residential Real Estate Lending, Comptroller's Handbook

Comptroller’s Handbook A-RRE Safety and Soundness Capital Asset Sensitivity to Other Adequacy Quality Management Earnings Liquidity Market Risk Activities (C) (A) (M) (E) (L) (S) (O) Residential Real Estate Version 1.0, June 2015 Version 1.1, June 16, 2016 Version 1.2, January 6, 2017 Office of the Comptroller of the Currency Washington, DC 20219 Version 1.2 Contents Introduction ..............................................................................................................................1 Overview ....................................................................................................................... 1 Mortgage Products .................................................................................................. 3 Home Equity Loan and Line of Credit Products .................................................... 5 Subprime Mortgage ................................................................................................ 7 Reverse Mortgage Loans ...................................................................................... 10 Investor-Owned RRE ............................................................................................ 12 Manufactured Housing.......................................................................................... 12 Affordable Housing .............................................................................................. 13 RRE Activities and Functions ..................................................................................... 15 RRE Loan -

![Notice of Information and Examples of Amortization of Home Loans [Notice to Consumers Under North Carolina General Statutes Section 24-1.1A(A1)(1)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1046/notice-of-information-and-examples-of-amortization-of-home-loans-notice-to-consumers-under-north-carolina-general-statutes-section-24-1-1a-a1-1-2221046.webp)

Notice of Information and Examples of Amortization of Home Loans [Notice to Consumers Under North Carolina General Statutes Section 24-1.1A(A1)(1)]

Notice of Information and Examples of Amortization of Home Loans [Notice to Consumers under North Carolina General Statutes Section 24-1.1A(a1)(1)] Note: North Carolina law requires a mortgage lender to provide this Office of the Commissioner of Banks Notice to a consumer who applies for a “home loan.” The lender must deliver or mail this Notice to the consumer within three business days after the lender receives the consumer’s loan application or the date of loan closing, whichever is earlier. This law defines a “home loan” as a loan (other than an open-end credit plan) for less than $300,000, obtained for personal, family or household purposes and secured by a first mortgage or first deed of trust on the consumer’s dwelling. Information on Home Loan Amortization When you obtain a home loan from a lender, you will be asked to sign a note that requires you to repay the principal amount you borrow, plus interest. You may also be required to pay sums into “escrow” so that your lender will have sufficient funds to pay your property taxes and insurance premiums when they become due. If you are delinquent in making your payments, you may be required to pay a late charge. The order in which your lender applies your payments to these various categories will depend on the specific terms of your loan documents and the manner in which your loan is administered. However, as between principal and interest, most lenders will apply your payment to the interest owed before any portion of the payment is applied to reduce the principal balance of the loan.